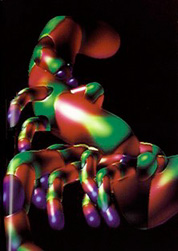

Yoishiro Kawaguchi's Mutation (1992) and

Cell: Artificial Life Metropolis (1993) differ from his early

3D computer art in their multifariously colored textures, their use

of new malleable, liquid forms, and their folding,

enveloping, mutating surfaces. Kawaguchi's recent animations appear

to be reflections of Deleuze's reading (1993) of the mathematics of

liquid folds, his study of infinite curvilinear forms.

Kawaguchi's 3D animations move by algorithms that simulate fluid and

elastic folding surfaces. Deleuze describes how the coherent parts

of fluid and elastic 3D bodies form folds such that when they

are continually divided to infinity in smaller and smaller pleats

and compressions of time and space, they always maintain their

cohesion. Reflecting on the geophilosophy of ripples, waves and the

surface crests of turbulent water, Deleuze defines matter as having

a porous, spongy or cavernous texture that can be surrounded and

penetrated by increasingly vaporous flows and waves of fluid. Like

Kawaguchi's liquid constructions, Deleuze suggests that the

folds of natural geography, of water, winds and veins of metal ore,

resemble the curves of conical forms that sometimes transfigure into

hyperbolas or parabolas.

Yoishiro Kawaguchi's Mutation (1992) and

Cell: Artificial Life Metropolis (1993) differ from his early

3D computer art in their multifariously colored textures, their use

of new malleable, liquid forms, and their folding,

enveloping, mutating surfaces. Kawaguchi's recent animations appear

to be reflections of Deleuze's reading (1993) of the mathematics of

liquid folds, his study of infinite curvilinear forms.

Kawaguchi's 3D animations move by algorithms that simulate fluid and

elastic folding surfaces. Deleuze describes how the coherent parts

of fluid and elastic 3D bodies form folds such that when they

are continually divided to infinity in smaller and smaller pleats

and compressions of time and space, they always maintain their

cohesion. Reflecting on the geophilosophy of ripples, waves and the

surface crests of turbulent water, Deleuze defines matter as having

a porous, spongy or cavernous texture that can be surrounded and

penetrated by increasingly vaporous flows and waves of fluid. Like

Kawaguchi's liquid constructions, Deleuze suggests that the

folds of natural geography, of water, winds and veins of metal ore,

resemble the curves of conical forms that sometimes transfigure into

hyperbolas or parabolas.

Mutation follows the metamorphosis of highly

abstract objects that flow, fold and fragment into innumerable

permutations. In Cell, Kawaguchi experiments with liquid

architectures as he builds a fugitive, molten megopolis of

artificial life. These 3D animations epitomize Kawaguchi's work

during the 1990's. Regarding form, his art is also an expression of

the hyperbolic geometry of curving surfaces and of a modulating,

synthesizing, liquid architecture capable of representing

elastic or deforming topological constructions in 3D cyberspace.

Like Malevich's architectones, Kawaguchi's 3D animations

extend formalism's concern with form, surface and texture to include

the language of abstract topology and folding surfaces.

As if he has Kawaguchi's work in mind, Novak (1991)

describes the unusual transformations in the liquid

architecture of cyberspace as the artist or animator generates and

varies objects in time. He perceives cyberspace as a modulating,

artificial architectural space. Liquid, visionary architectures

offer an excess of possibilities in shape, contour, texture and

topological construction. Novak suggests that we can now draw a

comparison between sculpture and computer constructions, because

liquid architectures, like hybrid abstract sculptures, produce

aesthetic beauty or sublimity, structure or lack of structure,

weight or weightlessness, lavishness (expense) or economy, details

or simplicity, uniqueness or universality.

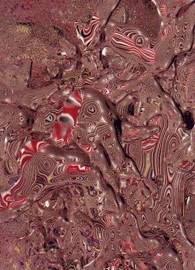

Kawaguchi's Mutation (1992) is a liquid,

morphing 3D meditation on the endless repetition of "biocosmic"

ideas in action. Kawaguchi uses growth algorithms and elaborate,

multilayered textures to visualize the fluidity of changing,

artificial, biomorphic shapes and creatures that exist at the

interstices of microbiology and computer code. He speaks to the

collapsing boundaries between art and science. Mutation

invokes visual impressions of conceptual art, geometric abstraction

and pattern painting, but its spatial structures actually reflect

the recursion, repetition and randomness of computer growth

algorithms in operation. Kawaguchi's "growth model" is a dynamic,

non-deterministic process that allows constructive mathematics to

take its course; a recursive structure of simple rules within

complexity.

Kawaguchi's Mutation (1992) is a liquid,

morphing 3D meditation on the endless repetition of "biocosmic"

ideas in action. Kawaguchi uses growth algorithms and elaborate,

multilayered textures to visualize the fluidity of changing,

artificial, biomorphic shapes and creatures that exist at the

interstices of microbiology and computer code. He speaks to the

collapsing boundaries between art and science. Mutation

invokes visual impressions of conceptual art, geometric abstraction

and pattern painting, but its spatial structures actually reflect

the recursion, repetition and randomness of computer growth

algorithms in operation. Kawaguchi's "growth model" is a dynamic,

non-deterministic process that allows constructive mathematics to

take its course; a recursive structure of simple rules within

complexity.

The fluid, seemingly part-serpentine, part-liquid

undulations of Mutation's artificial forms resemble the

movement of sand on the ocean's floor, the simulation of wave motion

or lava flow, or the ripple effects of water after an object's

touch. The radiating, shimmering texture surfaces on the abstract

objects are the composites of animated form, watery rippling

surface, manifold color, reflection and refraction. The

simulationist computer compositing and inflection of multilayered

texture maps using ray tracing techniques in 3D animation embody the

computer artist's concern with enfolded, planar or other elastic

topological surfaces in 3D cyberspace; the seamless, modulating,

liquid architecture of complex topological forms in digital

realms.

The fluid, seemingly part-serpentine, part-liquid

undulations of Mutation's artificial forms resemble the

movement of sand on the ocean's floor, the simulation of wave motion

or lava flow, or the ripple effects of water after an object's

touch. The radiating, shimmering texture surfaces on the abstract

objects are the composites of animated form, watery rippling

surface, manifold color, reflection and refraction. The

simulationist computer compositing and inflection of multilayered

texture maps using ray tracing techniques in 3D animation embody the

computer artist's concern with enfolded, planar or other elastic

topological surfaces in 3D cyberspace; the seamless, modulating,

liquid architecture of complex topological forms in digital

realms.

Like tangible, plastic, but less durable kinds of

digital architecture and construction, modernist artists of the past

also invented entire worlds without explicit reference to explicit

reality. For example, Malevich's architectones combine flat

and curved surfaces with round and rectilinear forms in three

dimensions and in ways that refuse symmetry. Curving non-Euclidean

forms are combined with Euclidean geometric shapes and spatial forms

(squares, cubic volumes and parallelograms) as to constitute the

basis for a new vocabulary of visual signs. Each architectone

is assembled from the artist's intuitive elements and not according

to mathematical formulas, as was the case with the contemporary work

of the De Stijl neoplastic movement. Mondrian, Malevich, Klee and

Kandinsky thus prefigure or antecede folding, liquid architecture,

but the similarities are sometimes astonishing. If we wonder, what

would life be like inside a cubist universe or a Magritte trompe

l’oeil, then we may find the answer inside Kawaguchi's

Mutation.

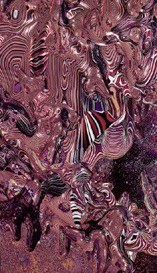

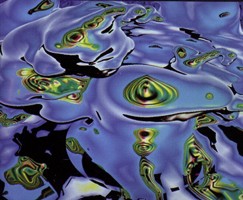

In Cell: Artificial Life Metropolis (1993),

Kawaguchi seems to take the idea of a folding, liquid architecture

more literally as he constructs a transmogrifying metropolis of

fluid skeletons and spines. He experiments with helixes and

mini-spirals that form aggregates of slippery, metallic caverns,

plateaus, and long columns of coils that snake like household

electric wire around cyborgian structures. The observer is unsure

whether she is journeying through a robotic body, or witnessing the

cool blue tectonic plate movement of some alien geological forms.

Like Haraway's cyborg figures (1985, 1997), Kawaguchi's artificial

creatures are hybrids of machine and organism, techno-genetic bodies

capable of "mating" by exchanging genetic and technical material so

that new configurations can emerge within the virtual arena. These

artificial figurations are important in delineating the ontological

nature of virtual worlds as they pertain to topological

representation and simulated visual forms. Following Eisenman

(1993), the enveloping surfaces of The Cell also hold the

potential for future cyberspace architectures derived from planar

folds and 3D volumes.

In Cell: Artificial Life Metropolis (1993),

Kawaguchi seems to take the idea of a folding, liquid architecture

more literally as he constructs a transmogrifying metropolis of

fluid skeletons and spines. He experiments with helixes and

mini-spirals that form aggregates of slippery, metallic caverns,

plateaus, and long columns of coils that snake like household

electric wire around cyborgian structures. The observer is unsure

whether she is journeying through a robotic body, or witnessing the

cool blue tectonic plate movement of some alien geological forms.

Like Haraway's cyborg figures (1985, 1997), Kawaguchi's artificial

creatures are hybrids of machine and organism, techno-genetic bodies

capable of "mating" by exchanging genetic and technical material so

that new configurations can emerge within the virtual arena. These

artificial figurations are important in delineating the ontological

nature of virtual worlds as they pertain to topological

representation and simulated visual forms. Following Eisenman

(1993), the enveloping surfaces of The Cell also hold the

potential for future cyberspace architectures derived from planar

folds and 3D volumes.

In a similar way, the work of Uri Dotan, computer

artist, in homage to 1960's painter Frank Stella, epitomizes the new

synthetic possibilities of virtual space as the complex creative

expression of expanded computer code in modeling, lighting, ray

tracing and transparency. The complex geometry of curved abstract

shapes elaborated in contrapuntal, curving, liquid 3D forms,

and in combination with heavy texture mapping, draws attention to

surfaces that both reflect and distort the virtual reality around

them. Dotan's digital pieces appear to be the simulacra of the

unseen, reminiscent but unlike objects in nature. Like Kawaguchi's

biocosmic constructions, they belong to no "real" space but to

hermetic, alternative worlds.

Returning to Kawaguchi's liquid figurations, his

recent work did not appear overnight, but are the offspring of many

years of tweaking and amplifying his growth model. His earliest

animation work, Pollen (1975) and Lines (1976)

duplicate the rotating movement of dotted lines and spirals

reminiscent of Gabo's work in plastic fibers from the 1920s and

1930's. Shells (1976), a prototype of the auto-multiplying

growth algorithm, animates the delicate, soft extrusion of hollow

wire-frame conch shells, horns and cones. In Growth: Mysterious

Galaxy (1983), Kawaguchi introduces some new organic structures,

such as his embryonic dolphins of liquid space, his red and green

metallic tendrils, and his pink undersea chorals. He elaborates the

play between surface and liquid submersion in Ocean (1986) as

tubular, twisted helixes wind around flourescent green undulating

ocean floors. Ocean also cameos Kawaguchi's first use of

ornate, reflective surface textures. Float (1987) follows the

voyage of unknown, perfectly golden, multifaceted globules through

luminous organic whirlpools.

Returning to Kawaguchi's liquid figurations, his

recent work did not appear overnight, but are the offspring of many

years of tweaking and amplifying his growth model. His earliest

animation work, Pollen (1975) and Lines (1976)

duplicate the rotating movement of dotted lines and spirals

reminiscent of Gabo's work in plastic fibers from the 1920s and

1930's. Shells (1976), a prototype of the auto-multiplying

growth algorithm, animates the delicate, soft extrusion of hollow

wire-frame conch shells, horns and cones. In Growth: Mysterious

Galaxy (1983), Kawaguchi introduces some new organic structures,

such as his embryonic dolphins of liquid space, his red and green

metallic tendrils, and his pink undersea chorals. He elaborates the

play between surface and liquid submersion in Ocean (1986) as

tubular, twisted helixes wind around flourescent green undulating

ocean floors. Ocean also cameos Kawaguchi's first use of

ornate, reflective surface textures. Float (1987) follows the

voyage of unknown, perfectly golden, multifaceted globules through

luminous organic whirlpools.

As testament to Kawaguchi's widely-recognized,

distinctive style, Festival (1991) features a marine carnival

of sea urchins, choral, sea amoeba and other fractalized

creatures. Surface textures are now so multifarious and fugitive

that they transgress the boundaries of the sublime or indescribable.

Kawaguchi's folding, liquid architecture is consequently a

dematerialized, ethereal, modulating architecture that is not

satisfied with space, form, light, weight, etc. in the physical,

bodily world, but corresponds to the merging or diverging of

abstract topological objects and elements in mind spaces.

As testament to Kawaguchi's widely-recognized,

distinctive style, Festival (1991) features a marine carnival

of sea urchins, choral, sea amoeba and other fractalized

creatures. Surface textures are now so multifarious and fugitive

that they transgress the boundaries of the sublime or indescribable.

Kawaguchi's folding, liquid architecture is consequently a

dematerialized, ethereal, modulating architecture that is not

satisfied with space, form, light, weight, etc. in the physical,

bodily world, but corresponds to the merging or diverging of

abstract topological objects and elements in mind spaces.

Rewriting formalism: abstract form in hybrid new

media

The formalists of the 1960's, Greenberg (1967),

Fried (1995), Krauss (1968), and Rose (1967), also express some

interest in how the 3D sculptural event in "real" Cartesian space

creates spatial metaphors between objects. In "Sculpture in Our

Time," Greenberg (1958) suggests that we permit sculpture greater

latitude of figurative allusiveness than other media, because it

remains tied to the third dimension. The illusion of organic

substance or texture is analogous to 3D in pictorial perspective

(such as that in 3D graphics or canvas arts) and, Greenberg

continues, this illusionism, literalness, or conceptual

content has become an advantage rather than a hindrance.

Greenberg chooses the sculptures of Jules Olitski as an epitome of

modernist abstraction, because they create the illusion of capturing

and folding surfaces of color in 3D space, an effect that seems to

render them weightless. Instead of the illusion of things, they

offer us the illusion of modalities, namely that matter is

incorporeal and weightless.

Greenberg emphasizes the radical

abstractness, or unlikeness to nature of Olitski's work (a

frequently used euphemism in the 1960's), and the "weightlessness"

of his sculptures in the way he says that they resemble Alexander

Calder's mobiles. "Weightlessness" is a term from abstract art that

implies free movement and a sense of not being grounded.

Weightlessness and modality are the basis of formalism's new

illusionism where matter is weightless and corresponds to some

non-Euclidean algebraic geometric space not unlike cyberspace.

Again, this kind of weightlessness belongs to the tradition of

non-monolithic sculpture that we derive from cubist collage and with

a cerebral and not a physical understanding of 3D form. Some

critics, such as Krauss (1968), carry the cubist metaphor of

illusionism to extreme conclusions: optical illusion becomes

tactile opticality, sensuous to touch, as Krauss pushes the

micrological analysis of the grain of sculptural surfaces to

inordinate refinements.

Picasso's cubism indulges in and extends

non-Euclidean paradigms of rounded or curved spaces in

discontinuous, fractured collages. While Poincaré wrote about the

tactility of curved space, Picasso's cubism enabled the radical

materialization of this new space. Mondrian points out that cubism

brings art to the threshold of a break with nature: It loses its

unity by expressing the fragmented character of the appearance of

objects. The tragic in nature is manifest as corporeality,

and this is expressed plastically as form and color, as

curvature and the "capriciousness" and irregularity of surfaces.

Similarly, Deleuze (1993) discusses the importance of the

plastic fold by showing us that matter is folded twice, once

under elastic forces (of water, wind, ore, or magma), and a second

time under plastic, derivative, organic and machinic forces.

Folding-unfolding can no longer be equated to tension-release, or

contraction-dilation, but to enveloping-developing and involution

evolution. The plastic organism is defined by its ability to

fold and unfold its own parts, not to infinity, but to a degree of

development inherent in its species. In the theory of non-Euclidean

curving surfaces, Deleuze distinguishes elastic forces from plastic,

"machinelike" forces that are present in modernist culture and

artifice, including the curving, pleated color surfaces of Olitski's

abstract sculpture.

Oliski's folding color surfaces defy the

literalness of edge and boundary. There appear to be no broken

surfaces. Greenberg writes, the grainy, tactile surfaces of color

contrive an illusion of depth as if those surfaces expand to contain

a "world of color" and light differentiations impossible to

flatness, but manage in some way not to violate flatness. Olitski's

"free" shapes and contours perhaps constitute the first attempt in

the history of art to realize pure color in three dimensions. Color

does not merely lie on Olitski's hybrid surfaces, but creates a new

kind of enriched surface and new spatial relationships. Resembling

Kawaguchi's molten configurations, each surface becomes a total

field of shape and form that avoids the determinate edges of the

rectangle in its flowing, folding convolutions. Olitski ability to

identify fluctuations of color value and hue makes spatially

developed 3D figures appear like shaped color (as opposed to

mere colored sculpture). Consequently, we may view his work in

hybrid pleated surfaces as a precursor to Kawaguchi's multiple

surface permutations.

Oliski's folding color surfaces defy the

literalness of edge and boundary. There appear to be no broken

surfaces. Greenberg writes, the grainy, tactile surfaces of color

contrive an illusion of depth as if those surfaces expand to contain

a "world of color" and light differentiations impossible to

flatness, but manage in some way not to violate flatness. Olitski's

"free" shapes and contours perhaps constitute the first attempt in

the history of art to realize pure color in three dimensions. Color

does not merely lie on Olitski's hybrid surfaces, but creates a new

kind of enriched surface and new spatial relationships. Resembling

Kawaguchi's molten configurations, each surface becomes a total

field of shape and form that avoids the determinate edges of the

rectangle in its flowing, folding convolutions. Olitski ability to

identify fluctuations of color value and hue makes spatially

developed 3D figures appear like shaped color (as opposed to

mere colored sculpture). Consequently, we may view his work in

hybrid pleated surfaces as a precursor to Kawaguchi's multiple

surface permutations.

Also, in a rare moment of self-criticism, Greenberg

admits that he may have been altogether wrong about sculpture and 3D

art, that "construction-sculpture," or "drawing-in-space sculpture"

in the late modernist period is making itself felt as the most

representative, fertile visual art of our time. Its no short

leap to the assumption that Greenberg permitted mixed-media hybrids

to salvage formalism in the 1960s, which later gave birth to its

left branch alternatives in postmodern and simulation art. As

Thierry de Duve (1996b) concludes from his study of 1960's art

polemics, two dimensionality is the last specific refuge of

modernist painting, but three dimensionality is the domain of the

new, generic, hybrid arts.

The theory of folding surfaces in Kawaguchi's

recent work

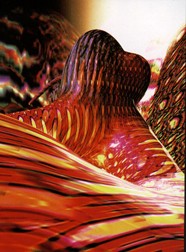

In Mutation (1993), Kawaguchi's color

surfaces seem to emit their own space and light within themselves

(enfolding space and light), rendering them eerily weightless. This

effect of enfolding, then unfolding space and light (of disposing

forms in space) is partially the result of Kawaguchi's subtle

chiaroscuro hue and shading, which produces an added

illusiveness. Deleuze describes the chiaroscuro effect, the

way the folding surface catches illumination and varies according to

the hour and the light of day, as a function of the fold of matter

and texture itself. Following Leibniz, Deleuze affirms that the fold

affects all materials (metal, paper, fabrics, water, living tissue,

the brain), because it determines and materializes form, becoming

"expressive matter" with different scales, speeds and vectors. Since

folding and the chiaroscuro effect are Baroque traits,

Kawaguchi's folding, pleating surfaces of color can be said to

resemble the overlaying folds and depths (crevices) of fabric or

paper. Deleuze defines three types of inflection of the fold: 1) the

ogive, or the pointed arch, that expresses the lines and

valleys of flowing liquid, 2) the morphological forms of living

matter, such as the dovetail, the butterfly and the hyperbolic or

parabolic umbilicus, and 3) the vortical inflection of the

variable curve, such as Koch's Baroque curve, that opens up on

infinite fluctuation and permutation. The pattern of contraction of

the latter complex spiral folds follows a fractal mode by

which new turbulences are inserted between the initial ones. In its

extreme form, the growing turbulence of folding ends in a "watery

froth" and the erasure of recognizable contour. As Deleuze says, the

Baroque is an "operative function" or "trait" which endlessly

produces folds, then twisting, turning, and pushing them into

infinity, fold over fold, one on the other.

Kawaguchi's abstract forms are therefore elastic

bodies in space whose cohering parts that form a fold, or a multiple

modulating surface of color. The fold does not appear to be

separated into parts, but may be divided into an infinity of smaller

and smaller folds (an endless folding, a 3D origami form). Baroque

folding and chiaroscuro effects become an aesthetics for a

kind of liquid architecture of 3D objects and spaces whose goal is

curvilinearity, the twisting line, the fluidity of matter and

the elasticity of bodies.

Whether they are found in abstract sculpture, the

contours of nature, or 3D simulated cyberspace, Deleuze (following

Leibniz) likens these complex folding interactions (inflections) to

the solid pleats of a "natural geography": the curves of conical

forms that sometimes end in a circle or an ellipse, or sometimes

stretch into a hyperbola or a parabola (1993, p. 6). He may also be

drawing on the continuing twentieth century interest in the curved

spaces of non-Euclidean geometries (such as Beltrami's hyperbolic

geometry) and new fractal geometric models. Eisenman (1993) is

inspired by Leibniz's turn away from Cartesian rationalism and in

his depiction of the point of the fold as the smallest element in

the labyrinth of the continuous. Eisenman also acknowledges Deleuze

for articulating a possible new relationship between vertical and

horizontal, figure and ground, breaking up the existing Cartesian

order of space in digital worlds.

Eisenman identifies Gilles Deleuze and René Thom as

the two most important contemporary theorists of folding surfaces.

Deleuzean extension is the outward movement of objects or

events along the surfaces of planes, rather than downward in depth.

Meaning is found at the surface; deep essences do not define forms.

Eisenman recounts how Deleuze conceptualizes the idea of the surface

object/event in the objectile, a contemporary technological

object such as any object that inhabits 3D cyberspace. The surface

object goes beyond the static framing of space: it necessarily

includes the temporal and topological variation of matter.

Similarly, in Thom's mathematics, the variable

curvature of the fold/unfold is the inflection of the pure event.

Transformations of objects or events do not occur according to a

privileged plan of projection, but instead are modeled by the

neutral surface formed from a variable curvature or fold. A complex

folding and unfolding can explain abrupt changes in form, which can

even be used to explain sudden or catastrophic events. Eisenman

explains, while a tiny grain of sand can trigger a landslide, we

already see the conditions leading up to the moment of movement to

be in place in structure or form. The fold in this sense contains

aspects of both figure and ground, but cannot be reduced to the

singular existence of figure or ground by itself. In a media age,

the changing surfaces of 3D objects in cyberspace are never

meaningful as static entities, but in their timely interaction in

configuration with one another.

The formalists' concern with the form, contour,

texture and relationality of flat and enfolded 2D surfaces is

extended in Kawaguchi's 3D animations, where curving, hyperboloid or

other stretchable or deformed topological surfaces emerge and take

shape. Folds and hyperbolas comprise the substance of

transformations and inflections of objects and events in 3D computer

architecture; a modulating, synthesizing, liquid architecture

capable of representing abstract constructions in digital, symbolic

spaces. Deleuze suggests that the "fold" is a series of convergent

points, or events, on a liquid surface, affirmed by

difference. In The Logic of sense, Deleuze (1990) discusses

how the ancient Epicureans failed to understand the quasi-causal

nature of folding surfaces; they failed in developing their theory

of envelops and surfaces, because they did not reach the idea of

incorporeal effects. Their simulations remained subject to the

single causality of bodies in depth. The Cynics and Stoics, however,

learned that sense appears and is played out on the metaphysical

surface of ideas, in the topological field of singularities,

representations, pure events and paradoxes. Meaning resides on the

surfaces of abstract objects and spaces, on the level of

appearances.

Consequently, both ideas and their effects are

superficial in simulationist new media that express seriality

and reproduction: The "depth" of meaning is realized on the surface

in the domain of visual, auditory and tactile representations, just

as the three-dimensional space is represented in a two dimensional

image or projection, which once flattened, can be mapped/morphed

from object to object in 3D rendering. Kawaguchi's 3D computer art

centers on a pure physics of surfaces, whereby events of a liquid

surface depend on digital transmutations on the level of code, in

auto-multiplying growth algorithms, but also on variations of a

surface appearance of the simulated, ideational quasi-cause. His

emphasis on surfaces translates consequently into a strong reliance

on image mapping and ray tracing techniques to create

photorealistic, 3D effects in his completed work or sequence.

Kawaguchi's liquid, biocosmic emanations also

appear to be 3D representations of machine, biology and computer

code. They seem to epitomize and embody Deleuze and Guattari's

(1987) innovative and far-reaching revaluation of the

machine/organism distinction in which the "machinic" is opposed to

both the mechanical and organic to allow for complex, open-ended

becomings within evolution. A truly "machinic" conception of

creative evolution must embrace a radical pluralism of technical,

semiotic, axiomatic and other machines that avoids the positing of

the "human" and the reified, humanized notion of what constitutes

autonomy on the machine. Perhaps Kawaguchi's animations are the

earliest attempts to meet Deleuze and Guattari's "machinic"

vision.

Kawaguchi's liquid, biocosmic emanations also

appear to be 3D representations of machine, biology and computer

code. They seem to epitomize and embody Deleuze and Guattari's

(1987) innovative and far-reaching revaluation of the

machine/organism distinction in which the "machinic" is opposed to

both the mechanical and organic to allow for complex, open-ended

becomings within evolution. A truly "machinic" conception of

creative evolution must embrace a radical pluralism of technical,

semiotic, axiomatic and other machines that avoids the positing of

the "human" and the reified, humanized notion of what constitutes

autonomy on the machine. Perhaps Kawaguchi's animations are the

earliest attempts to meet Deleuze and Guattari's "machinic"

vision.

Kawaguchi certainly provides a topological,

probabilistic and irrational animation space for his modulating

folds and 3D forms. Each of these liquid volumes constructs with the

others a noospheric "circulation" and a "cinema" of thought. Like

philosophy, Deleuze believes that the interactive, animated cinema

is a conceptual practice: In its twisting, folding and fissuring of

digital, informatic substance, it constructs and discovers new

pathways, connections and concepts. Although corporeal depth is

important, Deleuze believes that each thing is inscribed, sublimated

and symbolized on the liquid, noematic and metaphysical

surface, the "second screen" or realm of informatics that "hovers"

over bodies. He recognizes the brain as the "inductor" of that

second, invisible, cerebral, parabolic, metaphysical surface on

which all events fold and unfold. Thought brings about the

projection, conversion and induction of a physical folding surface

into a metaphysical surface; the projection in fact transmutes a

Euclidean space into an abstract, topological space. Kawaguchi's

recent animations, Mutation and Cell, confirm

Deleuze's belief that creating new connections in art means creating

them in the mind too!

Works Cited

Armstrong, M. A. Basic Topology. New York: Springer, 1983.

Benedikt, Michael, ed. Cyberspace: First Steps. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991.

Carroll, Noel. "Anti-illusionism in Modern and

Postmodern Art." Leonardo 21 (1988): 297-304.

Crary, Jonathan. Techniques of the Observer: On

Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge, MA:

MIT Press, 1990.

Deleuze, Gilles. Negotiations: 1972-1990. New York: Columbia University Press, 1995.

- - - . The Fold: Leibnitz and the Baroque. Trans. Tom Conley. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

- - - . The Logic of Sense. Trans. Mark Lester and Charles Stivale. New York: Columbia University Press, 1990.

Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. A Thousand

Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans. Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University

of Minnesota Press, 1987.

De Duve, Thierry. Clement Greenberg between the

Lines. Paris: Éditions Dis Voir, 1996a.

- - - . Kant after Duchamp. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996b.

Eisenman, Peter. Reworking Eisenman. London: Academy Editions, 1993.

Fried, Michael. "Two sculptures by Anthony Caro."

Artforum 2 (1968): 24-5.

- - - . "Shape as Form: Frank Stella's New Painting."

Artforum 11 (1966): 18-27.

- - - . "Art and Objecthood." Minimal Art: A Critical Anthology. Ed. Gregory Battcock. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995. 116-147.

Greenberg, Clement. Collected Essays and

Criticism, Volume 4: Modernism with a Vengence, 1957-1969.

Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1993a.

- - - . Collected Essays and Criticism, Volume 3:

affirmations and refusals, 1950-1956. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1993b.

- - - . "Recentness of sculpture." Art

International 4 (1967).

- - - . "Contemporary sculpture: Anthony Caro." Studio

International 9 (1965).

- - - . "Post painterly abstraction." Art

International (Summer 1964).

- - - . Art and Culture: Critical Essays. Boston:

Beacon Press, 1961.

- - - . "Sculpture in our time."

Arts Magazine 6 (1958).

Haraway, Donna. Modest_Witness@Second_Millenium.

FemaleMan©_Meets_OncoMouse™: feminism and technoscience. New York: Routledge, 1997.

- - - . "Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s." Socialist Review 80 (1985): 65-108.

Krauss, Rosalind. The Originality of the

avant-garde and other modernist myths. Cambridge, MA: MIT

Press, 1996.

- - - . "The Essential David Smith." Artforum 2 (1969): 43-9.

- - - . "On Frontality." Artforum 5

(1968): 40-7.

Mondian, Piet. The New art-the new life:

collected writings. London: Thames and Hudson, 1987.

Novak, Marcus, "Liquid architectures in cyberspace." Cyberspace: first steps.

Ed. Michael Benedikt. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 225-54.

Rose. Barbara. "Abstract illusionism." Artforum 10 (1967): 33-37.

- - - . "How to murder the avant-garde." Artforum 4 (1965a): 30-34.

- - - . "Looking at American sculpture." Artforum 3 (1965b): 33-41.

Shearer, Rhonda. "Chaos Theory and Fractal

Geometry: Their Potential Impact on the Future of Art." Leonardo 25 (1992): 143-52.

About the

Author

About the

Author Table of

Contents

Table of

Contents