Text by Robert Miltner

Images by Wendy Collin Sorin

Enculturation, Vol. 3, No. 2, Fall 2001

![]()

Where the Visual Meets the Verbal: Collaboration as Conversation

"Seeing comes before words," observes John Berger (7), though it could be argued that if words follow pictures, as when a poet creates a poem in response to a work of art, then words become a way of seeing. Collaborations between verbal and visual artists produce such insights, regardless of whether the poet responds to the painter or the painter to the poet, since each is speaking in turn in the artistic dialogue which collaboration produces. Yet "Artistic practice and art history have not always looked favorably upon collaborations" (Cappellazzo 9), given the Romantic notion of poets and painters working silent and solitary. Too often collaboration has been viewed as a form of compromise, at worst, as a compromising of the artist's or poet's individual talent for the sake of the comprehensive whole of the project at hand. Verbal and visual artists, however, are drawn to collaboration when the common project is mutually inspiring and offers an enriching symbiosis of actions and reactions with "each [artist] acting as the other's ideal audience" (Licata 11). This compromise, this audiencing, is a form of dialogue between the writer or artist and himself or herself, between the writer and the artist engaged in the collaboration, and between artists in general, since through dialogue they explore the commonalities of the creative process in lieu of the differences of the artistic product. Collaboration therefore takes the verbal and visual artist into new, shared territory, each having crossed a boundary to get there, and each giving and taking both from the shared work and from the conversation which collaboration allows.

"Seeing comes before words," observes John Berger (7), though it could be argued that if words follow pictures, as when a poet creates a poem in response to a work of art, then words become a way of seeing. Collaborations between verbal and visual artists produce such insights, regardless of whether the poet responds to the painter or the painter to the poet, since each is speaking in turn in the artistic dialogue which collaboration produces. Yet "Artistic practice and art history have not always looked favorably upon collaborations" (Cappellazzo 9), given the Romantic notion of poets and painters working silent and solitary. Too often collaboration has been viewed as a form of compromise, at worst, as a compromising of the artist's or poet's individual talent for the sake of the comprehensive whole of the project at hand. Verbal and visual artists, however, are drawn to collaboration when the common project is mutually inspiring and offers an enriching symbiosis of actions and reactions with "each [artist] acting as the other's ideal audience" (Licata 11). This compromise, this audiencing, is a form of dialogue between the writer or artist and himself or herself, between the writer and the artist engaged in the collaboration, and between artists in general, since through dialogue they explore the commonalities of the creative process in lieu of the differences of the artistic product. Collaboration therefore takes the verbal and visual artist into new, shared territory, each having crossed a boundary to get there, and each giving and taking both from the shared work and from the conversation which collaboration allows.

Yet, what is this process of collaboration, this dialogue between artists? Historically, collaboration is rooted in ekphrasis, writing in response to art, an activity which offers the poet several tasks, as outlined by J. D. McClatchy in his Introduction to Poets on Painters: Essays on the Art of Painting by Twentieth-Century Poets; he sees ekphrasis as a way "to copy and to learn," as a way of "describing" the art work, offering the poet a way both to "study figurative problems" and to pay "homage" (xiii). These activities, though, address the visual, imagistic dimension to ekphrasis, and McClatchy suggests that there may be another dimension that transcends the ekphrastic act, for, "By writing about a contemporary painting, a poet may cannily have found a useful way to let the poem talk about itself" (xiii). The key word here is "cannily," in that the poet, unintentionally and intuitionally, transgresses the act of ekphrasis, initiating a dialogue between poet and poem, poem and reader, poem and artist, as the poem is suddenly able to "talk about itself." And this talk has a specific direction, for "by praising or analyzing the painters . . . poets have found a sure way (their objective correlative, let's say) to describe themselves, or, more generally, to describe the creative process itself" (McClatchy xvi). Thus, through ekphrasis, the poet talks to himself in the writing of the ekphrastic poem, and additionally, the poem talks about itself by describing the creative process.

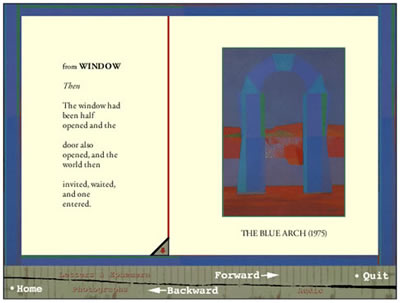

*Note: Robert Creeley's The Blue Arch is reproduced with permission.

1 | Next Node | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | Works Cited

|

Copyright © Enculturation 2001 |