Marcel O’Gorman, University of Waterloo

(Published November 18, 2019)

“But John doesn’t hold with teaching basket weaving where the splints come ready made. He teaches basket making, beginning with a living tree.

-- Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants

Figure 1: Caitlin Woodcock, Basketcase, 2017

This kit was inspired by the work of my student, Caitlin Woodcock, who recently fulfilled a Master of Arts in Experimental Digital Media (XDM) by completing several projects in the Critical Media Lab at the University of Waterloo. The project began in my “Digital Abstinence” course and sprouted into a larger undertaking. Caitlin wanted to challenge some of the prevailing stereotypes about hardware hacking and maker culture by locating her project in the history of domestic craft, in particular the craftwork of Mennonite and Indigenous women. She drew on the research of Tassoula Hadjiyanni and Kristin Helle, who observe that “craft making and its connective abilities strengthen. . . and reclaim cultural and gender identities as women craft makers reestablish their role as safekeepers of tradition” (77). Caitlin wove a basket, crocheted a sort of purse, and sewed a quilt, each designed to hold at least one cell phone. She equipped each artefact with sensors and a small display that invited users to temporarily hand over their cell phones and provided feedback when the phones were removed. In the words of Daniela K. Rosner and Sarah E. Fox, Caitlin’s work provides a “counter-narrative of hacking grounded in legacies of craftwork that disrupt conventional ontologies of hacking” (560). With Caitlin’s permission, I adopted her Basketcase project for a chapter in my book Making Media Theory, which provides instructions for several critical making projects, from conductive play dough to a useless box modeled after Shannon and Minsky’s “Ultimate Machine,” which is a box equipped with a single switch that does nothing more than turn itself off. This essay expands on Caitlin’s project as a way of reflecting on what it means to appropriate the practices of domestic craft for the purpose of a making media theory.

If Shannon and Minsky’s “Ultimate Machine” was inspired by the boys’ club of Bell Labs, the smartphone basket seems to emerge from a more feminine source, or more specifically, from a female domestic space, as already discussed. This gendering of the receptacle as female is an ancient trope, common in Greek myth—from Pandora’s box to the chest that hid earth-born Erichthonius, progeny of Gaia and the errant seed of Hephaestus[1] that Athena wiped from her leg and tossed to the ground. Moreover, in Ancient Greece, receptacles played a key role in feminine rituals, and more generally in domestic spaces. As François Lissarrague has suggested, objects of confinement such as boxes, clay pots, and baskets—objects that are “almost exclusively branded as female”—reflect the very confinement of women to the oikos (100). In an essay entitled “Women, Boxes, Containers: Some Signs and Metaphors,” Lissarrague looks closely at the iconography of Greek vase-paintings, ultimately concluding that they depict containers as “a matter of putting away, stocking, preserving; sometimes to conceal or to hoard, in short, to exercise a control over an indoor private space, where women are themselves detained” (93).[2] I’m not going to belabour Lissarrague’s point, which translates too neatly into a Freudian reading of Ancient Greek craft. Instead, I want to focus on the very last painting reproduced in his essay, a detail from a cup in which a Satyr is leaning so far into an open box that only his hindquarters are visible. As Lissarrague puts it in the final sentence of the essay, “The curiosity of the Satyr infringes . . . on the boundaries shaping Greek society; he cannot resist and dives, head first, in the women’s chest, even if it means losing his head” (100). It would be easy to make cavalier comments here about male academics studying women’s history with their heads in the sand—or somewhere more indecent, for that matter. But I have other intentions. For it is at the end of Lissarrague’s essay, at the point where the curious satyr loses his head, that this chapter on baskets begins.

Although I know better, I would like to think that Lissarrague’s final sentence was inspired by Georges Bataille, who wrote in the first issue of the experimental journal Acephale:

Human life is defeated because it serves as the head and reason of the universe. Insofar as it becomes that head and reason it accepts slavery. If it isn’t free, existence becomes empty or neuter, and if it is free, it is a game. The earth, as long as it only engendered cataclysms, trees, and birds was a free universe; the fascination with liberty became dulled when the earth produced a being who demanded necessity as a law over the universe. (“The Sacred Conspiracy”)

All of the calculating reason, the Freudian machinery powering the discourse on woman-as-container comes to a halt when the Satyr becomes Satyr-box: half-man, half-goat, half box, a formula that requires a new understanding of mathematics, one based not on logical summation but on indeterminate becoming. Bataille’s defense of headlessness provides the first item of instruction for this lesson on basket weaving. We begin then, with an understanding of making as an activity of becoming, and as an opportunity to lose our heads.

In his book Making, Tim Ingold describes a class exercise in which students were taught how to make baskets out of willow by standing thin branches upright in the sand and weaving them together until the form of a receptacle emerged. Ingold recalls that the students were surprised by the “recalcitrant nature of the material” (22), and they finished the day with aching muscles. After all, as Ingold puts it, “there is no obvious point when a basket is finished” (23), and so the students’ work was delimited primarily by physical exertion. It is this interplay of human bodies and “recalcitrant nature,” the tension of muscles and willow to which Ingold draws our attention. Rather than understanding making as an imposition of human will on nature, Ingold asks us to understand the students’ creations as an interplay of matter, as “the drawing out or bringing forth of potentials immanent in a world of becoming” (31). The students entered this project headlessly, without a prior design, and they were left to follow the directions of the materials in their hands, engaging directly with what Deleuze and Guattari, following Gilbert Simondon, have described as “matter-flow.” As Ingold puts it, “Artisans or practitioners who follow the flow are, in effect, itinerants, wayfarers, whose task is to enter the grain of the world’s becoming and bend it to an evolving purpose” (25).

Ingold’s goal here is not to provide instructions for some sort of generative art, the woven equivalent of automatic writing; rather, he is asking makers to take account for the complex field of materials and interactions in which their activity unfolds. This is making as morphogenesis. In an essay aptly entitled “On Weaving a Basket,” Ingold suggests that “Since the artisan is involved in the same system as the material with which he works, so his activity does not transform that system but is—like the growth of plants and animals—part and parcel of the system’s transformation of itself” (345). Ingold ultimately asks for a revision of the word making, calling instead for a practice of weaving. Whereas making regards “the object as the expression of an idea,” weaving regards the object as the “embodiment of a rhythmic movement” (346). The result is an anti-platonic understanding of fabrication in which “the forms of objects are not imposed from above [e.g., by a rational, disembodied mind], but grow from the mutual involvement of people and materials in an environment” (346). This understanding of making as morphogenesis might even complicate how we understand the work of a master craftsman like Hephaestus; after all, “Even iron flows, and the smith has to follow it” (27).[3]

Ingold's reference to bending "the world's becoming" to "an evolving purpose" brings to mind not only the bent willow twigs that bring baskets into shape, but also the bodies of the students bent over their projects (25). What I see in this scene of bending, inspired by Adriana Cavarero's concept of "inclination," is an alternative to the glorification of Homo Erectus, which plays a heroic role in Ingold's conception of humans and technics as co-constitutive in a theory of human origins. The students bent over their willow twigs suggest something else: a Homo Inclinus perhaps, an "inclining [of] the subject toward the other" (Cavarero, 11), a "subjectivity marked by exposure, vulnerability, and dependence," an origin theory based on relationality rather than on rectitude (11).

We have come a far way then, from a course in “underwater basket weaving,” an expression once used to describe any number of supposedly useless courses in the arts and humanities curriculum (”Underwater Basket Weaving”). Basket weaving as described here has become a philosophical, erotic, and possibly ethical activity performed by individuals who understand their actions not as masters of nature, but as agents in a field of becoming. As a learning opportunity, basket weaving introduces students to the practices and politics of haptics, a form of knowing that challenges the predominant senses of seeing and hearing, the so-called distant senses, which dominate Western education. As Laura U. Marks suggests in her book Touch: Sensuous Theory and Multisensuous Media, haptics require a form of knowing in which bodies are conspicuously entangled, or woven, an “erotics that offers its object to the viewer but only on condition that its unknowability remain intact, and that the viewer, in coming closer, give up his or her own mastery” (90). Not surprisingly, I first came upon this quote in a book by Jack Halberstam. To understand making as weaving, to embrace the unknowability that comes with haptics, is to accept the possibility of failure, the possibility that our idea of what we are making may very well not materialize in ways that we hope and expect. [4] I have encountered this disappointment many times with students whose handmade projects do not satisfy the platonic image they held in their heads when they began. But the failure they experience, if it can be called failure at all, is only the failure of a head guided by a will to mastery.

Making media theory should not be understood as the materialization of platonic designs, but rather as an embodiment of becoming, a headless tension between muscle and matter with unknowable results. When these are the conditions of fabrication, there can be no failure except in an inability or refusal to recognize making as a complex process of becoming. Understanding making as a form of haptics runs counter to rhetorics of making that are complicit with technocultural logics, that understand matter as beholden to the will of a skilled craftsman, technician, or computer programmer. Making as haptics can lead to a happy acknowledgment of the limits of human mastery over nature, including an acknowledgment of our own species limitations. “The close senses,” says Laura Marks, such as touch, smell, and taste,

which index both the material world and the materiality of the body that perceives with them, insist upon mortality. Thus, a materialist aesthetics can find value in the close senses precisely for their grounded, provisional, and ephemeral character. The immanence and materiality of the proximal senses can thus be the ground of aesthetics, knowledge, and indeed ethics. (129)

As I argue in Necromedia, an acknowledgement of our own mortality need not be an endorsement of morbid depression but rather a call to recognize with curiosity our vulnerable entanglement in a material world beyond our understanding. Therein lies the recipe for an ethics. Making media theory requires a combination of critical distance and haptic proximity as the theorist/maker loses their head in the materiality of things.

For an essay that promotes headlessness it seems ironic to invoke the heady theories of Georges Bataille, Gilbert Simondon, and Deleuze and Guattari. This is perhaps one of the many perils of making media theory, which asks makers to shuttle between the distant and close senses that unfold in the field of technocultural being. I am compelled, as I write this, to start over altogether and draw on a system of knowledge other than the European philosophical canon invoked here. Let’s consider another tradition of basket weaving then, as a way of complicating both the Greek-Freudian machinery that started this essay and the continental philosophy that bodied it forth.

When John Pigeon makes a basket out of black ash, he begins by finding the right tree and asking it for permission to be felled. He then peels the bark away and uses a hammer to loosen a strip of flesh from the tree. This strip is usually a single growth ring thick, each strip signifying a year in the life of the tree. Finally, John Pigeon carefully cuts the strips into long ribbons of flexible ash, suitable for weaving. In Braiding Sweetgrass. Robin Wall Kimmerer describes her experience of learning to make a black ash basket in a workshop with the renowned Potawatomi basket maker. Kimmerer describes how, in every step of the process, she encountered the recalcitrance of the ash, the tension between weaver and wood. As she began weaving, she noticed how the ash “resists the pattern” she was trying to impose on it, but eventually, through a process of negotiation and reciprocity, lent itself to a shape that would become a basket. There are many lessons here for an ethical maker, but among them is a consideration for the life and origins of the materials entangled in the process of becoming. “Today, my house is full of baskets,” observes Kimmerer, “They remind me of the years of a tree’s life that I hold in my hands” (154). She then goes on to consider the origins of other objects in her midst:

What would it be like, I wondered, to live with the heightened sensitivity to the lives given for ours? To consider the tree in the Kleenex, the algae in the toothpaste, the oaks in the floor, the grapes in the wine; to follow back the thread of life in everything and pay it respect? Once you start, it’s hard to stop, and you begin to feel awash in gifts. (154)

Kimmerer even traces the lineage of her metal lamp. She stops, however, when she encounters the plastic on her desk. “I can muster no reflective moment for plastic,” she writes, before tracing it back to the fossilized diatoms and marine invertebrates transformed by the shifting of the earth into oils that could be refined to produce these industrial objects. Kimmerer concludes: “Being mindful in the vast network of industrialized goods” poses too much of a challenge. “We weren’t made for that sort of constant awareness” (155).

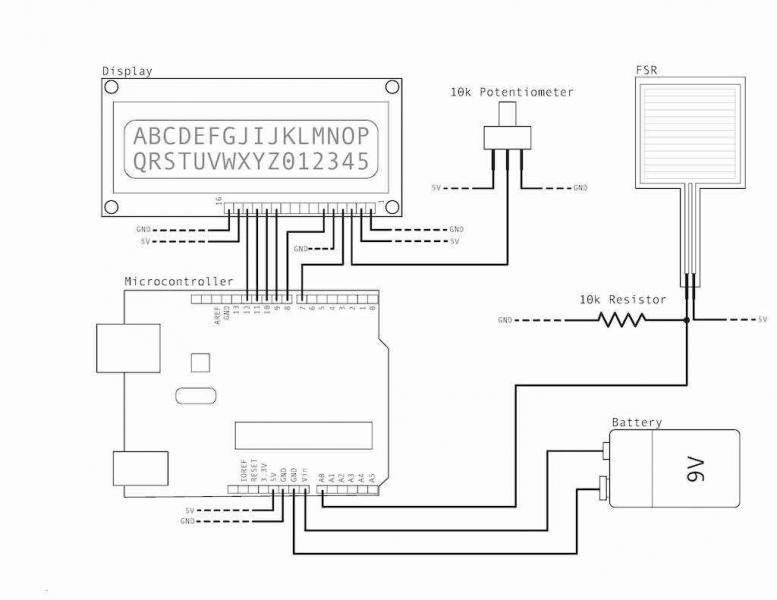

The kit described in this essay asks readers to make a basket designed to hold a cell phone, or perhaps more than one phone. The project is designed to provoke reflection on the materials and bodies that it summons forth. What’s more, this project cannot escape the politics of appropriation (e.g., the appropriation of domestic craft practices, a student project, queer theory, and Indigenous wisdom),[5] a consideration that should also be woven into the process of making the basket. Some makers may wish to follow the example of Caitlin Woodcock, and add a sensor and LCD display to their basket. In this case, they should carefully consider what that display will say to those who encounter it, both before and after their cell phone is placed on the sensor in the basket. They should also consider the provenance of these electronics and their ultimate destiny as potentially toxic digital debris.[6] Finally, I have included the source code and a wiring diagram for the sake of documenting Caitlin’s project, and makers are of course welcome to draw on these digitally-oriented resources that will likely lose their functionality over time, as hardware and software protocols change. The same can’t be said for the procedures of fabrication and functionality of the basket.

Instructions

There are too many types of baskets for me to land on a single model for instruction. Rather than providing precise instructions on how to weave a single type of basket, I encourage readers to research basket making online, and draw from one of the many sets of instructions available. But consider the source carefully. Is there a cultural or family tradition behind this basket? Better yet, rather than searching online, readers could visit a local shop or market where artisan baskets are sold, and conduct research, possibly contacting the weaver, before deciding on what kind of basket to make. Consider taking a basket weaving class at a local cultural centre or even at an Indigenous community centre. Whatever the case may be, pay attention to the materials and their origins, and think of the relationship between the weaver’s body, the basket, the cell phone(s) it is going to hold, and the bodies of those who will make use of this basket.

The following instructions are provided for those who wish to integrate an LCD display and sensor into the basket. The list of materials, wiring chart, and code were provided by the former Lab Technician of Critical Media Lab, Matt Frazer, and are reproduced here with the permission of Caitlin Woodcock. As noted already, these materials may be used (debugged, updated, and hacked) to produce a replica of Woodcock’s Basketcase project, but they are reproduced here primarily for the sake of a discussion and reflection on morphogenesis.

Supplies:

- 9V battery

- 9V battery clip

- Arduino Uno (or similar)

- 16x2 LCD character display or similar

- Force sensing resistor appropriately sized for the bottom of a basket

- Breadboard

- Hookup wire

Wiring Chart:

Note that the wiring chart below includes a resistor between the LCD display and the power source. This may be necessary, depending on your configuration.

Figure 2. Wiring chart.

Code:

The Arduino sketch for this project can be found at: https://github.com/hyperrhiz/basketcase

[1] Hephaestus’ lofty status as an engineer to the gods is complicated not only by his apparent disability (he is consistently depicted with a lame foot) but also by his attempted rape of Athena, who approached him to craft a shield for Achilles. I discuss this issue at length in Making Media Theory.

[2] Lissarrague notes that in Lysistrata, Aristophanes plays on the words kiste, or basket, and kusthos, “a vulgar expression for the female sexual organs” (98). It is fitting that today, the word basket is slang for male sexual organs, referring to “the outline of the male genital area as viewed through pants/swimsuit/undergarment” ( “Basket”).

[3] Here, Ingold is paraphrasing Deleuze and Guattari, who draw on metallurgy in A Thousand Plateaus to illustrate the variability of matter. Jane Bennett draws on the same material to describe the vitality of inorganic life in her book Vibrant Matter.

[4] Halberstam’s Queer Art of Failure encourages readers to embrace failure as a means of challenging the phallogocentric strictures of the academic apparatus. In his book Trans*, Halberstam applies the concept of haptics to describe the process of becoming transsexual, which involves a making, unmaking, and/or re-making of self. In his terms, the language of the haptic can be an “alternative to the medical, the legal, and the mediatized will to know and as a remapping of the gendered body, not around having or lacking the phallus but around manipulating and knowing via the hand, the finger, the arm, the body in bits and pieces. The haptic body and the haptic self are not known in advance but improvised over and over on behalf of a willful and freeing sense of bewilderment” (92).

[5] For a carefully executed theory of Indigenous new materialism, see Jennifer Clary-Lemon, "Gifts, Ancestors, and Relations: Notes Toward an Indigenous New Materialism." Enculturation, November 12, 2019. http://enculturation.net/gifts_ancestors_and_relations.

[6] In Digital Trash: A Natural History of Electronics, Jennifer Gabrys asks, “Where is the dirt of electronics? How does dirt inform the making of electronic materials and spaces? Electronic waste presents a crucial case study of dirt, of both how it is generated and where it is distributed” (17).

“Basket.” Urban Dictionary, 2003. https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=Basket.

Bataille, Georges. “The Sacred Conspiracy.” Translated by Mitch Abidor. Acéphale, June 24, 1936. Retrieved from Marxists.org. https://www.marxists.org/subject/anarchism/bataille/sacred-conspiracy.htm

Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Duke UP, 2010.

Clary-Lemon, Jennifer. "Gifts, Ancestors, and Relations: Notes Toward an Indigenous New Materialism." Enculturation, November 12, 2019. http://enculturation.net/gifts_ancestors_and_relations

Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. Continuum, 2004.

Gabrys, Jennifer. Digital Rubbish: A Natural History of Electronics. U of Michigan P, 2011.

Hadjiyanni, Tasoulla, and Kristin Helle. “(IM)Materiality and Practice: Craft Making as a Medium for Reconstructing Ojibwe Identity in Domestic Spaces.” The Journal of Architecture, Design and Domestic Space, vol. 7, no. 1, 2010, pp. 57-84.

Halberstam, Jack. Trans*: A Quick and Dirty Account of Gender Variability. U of California P, 2018.

---. The Queer Art of Failure. Duke UP, 2011.

Ingold, Tim. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. Routledge, 2013.

---. The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. Routledge, 2000.

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Milkweed Editions, 2013.

Lissarrague, François. “Women, Boxes, Containers: Some Signs and Metaphors.” Pandora: Women in Classical Greece, edited by Ellen D. Reeder, Trustees of the Walters Art Gallery in association with Princeton UP, 1995, pp. 91-101.

Marks, Laura U. Touch: Sensuous Theory and Multisensory Media. U of Minnesota P, 2002.

O'Gorman, Marcel. Making Media Theory: Thinking Critically with Technology. New York: Bloomsbury (forthcoming).

——. Necromedia. U of Minnesota P, 2016.

Rosner, Daniela K. and Sarah E. Fox. “Legacies of Craft and the Centrality of Failure in a Mother-Operated Hackerspace.” New Media & Society, vol. 18, no. 4, 2016, pp. 558-580.

Simondon, Gilbert. L’individu et sa génèse phsico-biologique. Presses Universitaires de France, 1964.

“Underwater Basket Weaving.” Wikipedia, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Underwater_basket_weaving