Lauren M. Bowen, University of Massachusetts Boston

(Published June 8, 2020)

Introduction

As the global population of older adults continues to grow, the shifting age demographics have momentous implications for individuals, families, communities, and employers—all of which have consequences for writing and literacy. The small but growing effort to orient writing studies research toward a lifespan perspective is, therefore, well-timed (Bazerman et al.; Dippre and Phillips). This essay contributes to lifespan writing research by considering how literate identity—a condition of great interest in studies of developing writers in earlier stages of life, particularly in school and workplace contexts—evolves through later-adult life. In particular, this study examines how people (re)story their literate lives in old age through and against engagements with literacies and literacy technologies and their choices to appropriate, resist, or transform literacies.

In addition to contributing to momentum on lifespan studies of writing, this project also engages with the recent “identity turn” in writing studies—as exemplified by identity-centered, meta-disciplinary discussions at conferences (Inoue) and in web forums (e.g., WPA-L Working Group and nextGEN), as well as by the steady output of articles and book-length works exploring the myriad ways identity and difference matter to rhetoric, writing, and literacy. In this essay, I advocate for an addition to the field’s identity vocabulary: age identity. Reporting on a materially attuned, narrative-based research study of older adults’ (dis)engagements with digital literacies at a historic moment, this essay explores a central question: How does age identity contribute to individuals’ agentive choices to appropriate, resist, or transform literate identities in later life?

To answer this question, this essay joins literacy studies, age studies, and new materialist perspectives of rhetorical activity to examine how literate identity and age identity are constituted, in tandem, through the life stories of seventeen adults over age 65. While life story interviews are a well-established empirical method for the study of identity as a discursive construction, new materialist writing studies scholars have shown that literate and rhetorical activity are distributed within ecologies of human and non-human agents. Thus, this article centers on adults' rhetorical partnership with evocative objects: the non-human entities that prompt—and haunt—participants’ rhetorical articulations of narrative, memory, and self. In addition to demonstrating the value of such methodology for rhetorical studies of identity, this essay offers age as a rhetorical framework of self-identification that motivates individuals to appropriate, resist, or transform literate identities—particularly those involving emergent technologies.

Age Identity and Literate Identity: Some Definitions and Principles

Distinct from chronological age, “age identity” refers to a subjective, rhetorically constructed awareness of age. Much like gender, race, and ability, age identity includes both physical (biological) and sociocultural dimensions. As a social identity category, age identity includes the relative sense of feeling “young” or “old,” which does not necessarily coincide with chronological age. For example, people typically report feeling older than their chronological age until age twenty-five, at which point they begin to report feeling younger than their chronological age (Galambos et al.). Age identification also changes in the short term based on a contextual sense of social appropriateness—such as feeling “too old” to change careers, but “too young” to retire. Simultaneously, longer-term transitions to a new sense of age identity happen gradually and are prompted by a disruption to a sense of continuity; for example, an illness or injury, a milestone birthday, or the death of a peer can all contribute to an emerging awareness of oneself as aging or old.

Age identity is always, in part, culturally constructed (Beauvoir). Elsewhere I have described the rhetorical construction of old age through dominant discourses, calling it the “curriculum of aging" (Bowen, “Beyond Repair”). This includes the circulation and construction of age-based stereotypes and the accumulation of meaning around age-associated ideas and images, such as the appearance of wrinkles or gray hair. Since age-based stereotypes, as Angela Crow notes, “may relate to the expectations we establish for ourselves and others who fall into the category of older,” the rhetorical construction of age identity may contribute to age-based assumptions and expectations for literacy (35–36).

In this essay, I consider how expressions of age identity converge with expressions of “literate identities”: that is, the multiple, multifaceted, and evolving ways someone is recognized, by the self and others, as the “kind of person” (Gee, “Identity” 99) who makes agentive use of a “range of practices involved in the coding of socially and culturally relevant symbols” (Lewis and Del Valle 309). Theorizing a specific expression of literate identity—what she calls “writer identity”—Roz Ivanič proposes four interrelated dimensions:

- Autobiographical identity is constituted by the experiences, ideas, discursive repertoires, and other resources writers bring to the act of writing (24-25).

- The discoursal self is “the portrayal of self which writers construct through their deployment of discoursal resources in their own written texts” (327).

- Self as author captures the relative degree to which individuals see and present themselves as authors (23-24).

According to Ivanič, these first three aspects of identity are activated when “an actual writer [is] writing a particular text” and are shaped by a fourth aspect of identity:

- Possibilities for self-hood, rendered by the “abstract, prototypical identities available in the socio-cultural context of writing” (23).

Like Ivanič’s concept of writer identity, literate identity is composed by the situated interplay between individual and sociocultural aspects of identity; however, the individual aspects of literate identity—as I use the concept here—are not only incited during “live” literate activity. Instead, literate identities can be appropriated, resisted, and transformed even when an individual does not read or write. My theoretical framework for defining and examining literate identities is built on six common principles familiar to literacy researchers, distilled in Table 1 for clarity.

|

Principle 1. Literate identities are multiple. |

Because literacy is socially situated (Street), multiple literacies emerge in response to different social domains (Barton), generating countless possibilities for the adoption of situationally specific literate identities. |

|

Principle 2. Literate identities interact and change over a lifespan. |

Literate identities “continually shape and reshape one another” as they bump against, change, and are changed by engagement with other literacies (Roozen 568). This change also occurs as literacy practices are repurposed across social domains, thereby opening and foreclosing social footholds in new contexts (566). |

|

Principle 3. Literate identities converge with other dimensions of identity. |

In a process sometimes called “lamination,” literate identities converge with other social identities in relatively durable “collections that have become coordinated and juxtaposed in practice” (Moje and Luke 431). Through literate practice, social footings become juxtaposed and laminated onto one another (Prior), like layers of varnish that thicken over time as an individual moves across social contexts and adopts ever-diversifying social positions (Moje and Luke 430). |

|

Principle 4. Literate identities are unequally available. |

The milieu(x) into which someone is socialized impacts the ways that literacies will be used and valued. For this reason, discrepancies in literate identities emerge, often marking divisions among identity groups such as race/ethnicity, social class, and gender (Banks; Heath; Vee). As mainstream uses and values of literacies shift over time, members of some social groups will be better socialized than others to take up literate identities advantageous to the pursuit of financial and social capital (Brandt). |

|

Principle 5. Literate identities carry ideological weight. |

As they accumulate, transform, and fade over a lifetime of cross-contextual movement and socialization, literate identities also become sedimented with dispositions and practices associated with those literacies. Folded into what Gee calls Discourses—those “saying(writing)-doing-being-valuing-believing combinations” (Gee, “Literacy” 6)—literacies participate in the formation and enactment of an ideological “identity kit,” which involves “sets of values and viewpoints,” which sometimes contradict (19). |

|

Principle 6. Literate identities are rhetorically constituted by the self and by others. |

Although literate identities are rhetorically constituted through authoritative discourse (including school-based assessments) that necessarily shape “ideological interrelations with the world” (Bakhtin 342), individuals can constitute self-identity by taking up, rejecting, or reframing literate identities through enactments and representations of the self: in the stories individuals tell about themselves (Lorimer Leonard), in the texts that they produce (Ivanič), and in the activities they pursue and transfer across contexts (Roozen and Erickson). |

Table 1. Principles of Literate Identity Theory

Evoking Identities: A Materialized Lifespan Methodology

To theorize age identity’s entanglement with literate identities, I analyze older adults’ rhetorical constructions of identity at a moment of seismic change in their “literacyscapes” (Leander). Between 2010 and 2014, the US (and much of the world) saw a surge in social media and mobile technology adoption. In December 2008, 26% of adults in the US were social media users, including only 2% of adults over age sixty-five, but by January 2014, 62% of adults, including 27% of adults over sixty-five, were using at least one social media site (Pew Research Center). Concurrent with the social media boom, the emergence of mass market smartphones marked the early days of what would become a near-ubiquitous literacy and communication technology among US adults age 18 to 49 (Pew Research Center).

Against this historical backdrop, between 2010 and 2014, I interviewed seventeen adults in the northeastern US, all over age 65 with varied education and socioeconomic backgrounds. While age identity is expressed and cultivated from birth, later life is a particularly dynamic phase of the lifespan in which to examine age identity. Later life includes distinctions between what Mary Catherine Bateson calls “Adulthood II” and old age. Because Adulthood II—a phase whose duration and accessibility are strongly correlated with socioeconomic privilege—often involves removing or decentering prominent roles from earlier adulthood (e.g., retirement from work) but can also include a transformation or even expansion of those earlier roles (e.g., starting a second or third career). Inevitably, Adulthood II cedes to old age in which biological decline precedes end of life. Experiences with such physical changes in later life incite ongoing confrontations with age identity.

Added to these individual changes, the seismic shift toward digital literacy and communication presents a kairotic moment to consider both how confrontations with changes to the sociocultural literacyscape create opportunities to confront age identity and, conversely, how confrontations with age identity create opportunities to reconsider participation in shifting literate economies. As Suzanne Kesler Rumsey finds in her research on older adults’ literacy practices, shifts in literacyscapes, as well as shifts in bodily capacity, present older adults with choices to adopt, to adapt, or to alienate themselves from new or familiar literacy practices (“Heritage Literacy” 578); to “hold on” to literacies as vehicles of “dignity, independence, and agency”; or to accept “letting go” of literacies no longer physically or cognitively accessible (“Holding on” 99).

To view participants’ responses to this transitional moment from a lifespan perspective, I adopted the method of life story interviews (Atkinson; Bertaux and Kohli). Drawn from oral history and ethnographic methods, life story research is a narrative methodology distinct for its emphasis on “looking at life-as-a-whole” to discern patterns within an individual life (Atkinson 3). Through similar life history approaches, other literacy researchers have accounted for literate identity as multiple, interacting and changing over the lifespan, intersecting with other social identities, sedimented with ideology, and unequally available (Brandt; Selfe and Hawisher). The life story approach, however, places a particular emphasis on narrative performance; therefore, this study examines the telling of life stories as rhetorical practices of identity-making.

While traditional life story studies attend primarily to language, the work of new materialist rhetoricians suggests that language is only one aspect of our storied selves. Literate practices are made possible only through the “radical withness” of humans and non-humans (Micciche 502), such that a writer is a “hybrid actor” merging human and tool (Gries 81). If the telling of a life story is a rhetorical practice, then it, too, is not only the product of an individual rhetor’s discourses but also the constantly (re)negotiated output of an ecological rhetorical practice that is “irreducible to an individual’s conscious agency” (Boyle 43). These interactions within ecologies of humans, literacy tools, and textual objects have implications for literate valuations and literate identities not just in particular moments of inscription but also over a lifespan. Jim Porter, reflecting on evolving relationships with literate technologies present in his own literacy narrative, claims, “The technological past matters. It shapes the writer and writes the body in significant ways—etching itself on the writer’s consciousness and body, influencing how the writer learns to compose and how the writer communicates in a social milieu” (389).

Conscious awareness of the “etching” done by writing tools and spaces can afford opportunities to agentively and kairotically change relationships with writing tools and spaces, thereby allowing for a new sense of text (Ching), a new sense of writing’s places (Rule), and consequently a new sense of which kinds of writing are possible. The methodological orientation of this study extends this line of thinking a notch further: objects participate not just in creating a sense of text and process but an evolving, fluid sense of the literate self—both the literate identity that is (here and now) and the literate identities that might be. In another empirical study of writers’ material habitats, Cydney Alexis traces the symbolic role of Moleskin notebooks across three different participants’ writing lives. Alexis compellingly illustrates that individuals invest deep and meaningful attachments to material objects as often-sacred representations of their identities as writers, such as using writing tools “as self-expression in service of building an identity around writing” (Alexis, “Symbolic Life” 43). Like Alexis, I am interested in how “materials tell us about how we come to identify as writers, develop a writing identity, articulate it for others, and negotiate it with objects” (Alexis, “Material Culture” 84).

To attend to the material and non-human components of the ecological rhetorical practice of narrating identity, I expand classic life story methods beyond the language-only interview. To foreground objects both as emotional and rhetorical companions in and across different phases of the lifespan and as provocateurs of the rhetorically constituted self as literate and aged, I developed a supplemental interview method called the literacy tour, in which participants guide me through spaces where reading and writing happened most often in their lives (Bowen, “Literacy Tours”). These tours attune both participant and researcher to material artifacts that evoke autobiographical memory and a narrated literate self. Although literacy tools and texts are crucial for the production and circulation of agency and literate identity (Dippre), this study is oriented capaciously toward evocative objects: ordinary things recognized as “companions to . . . emotional lives” and “provocations to thought” (Turkle 5). Assemblages of such meaningful artifacts constitute what Jennifer González calls autotopographies: the “private-yet-material memory landscape . . . made up of the more intimate expressions of values and beliefs, emotions and desires, that are found in the domestic collection and arrangement of objects” (133).

Each of the seventeen participants was interviewed once, and each interview lasted between one and three hours. Semi-structured life story interviews and literacy tours were conducted on the same occasion, usually interwoven. Interviews were conducted in participants’ homes, which all identified as the primary site of their everyday literate activity. The interview and tour method yielded raw data of four general types: audio recordings, transcribed in full; video recordings of literacy tours and most life story interviews; photographs of key objects or sites; and occasionally textual artifacts, as offered by participants as demonstrations of their literacy practices.

Because a life story should ultimately “pull together the central elements, events, and beliefs in a person’s life” (Atkinson 19), descriptive coding was useful for establishing coherence and continuity amid the fragmented episodes—that is, it served as a guide to interpretation. Descriptive coding sorted narrative data within three broad, overlapping categories:

- Life stage (to establish chronology): childhood, early adulthood, adulthood I, adulthood II

- Social domain (to establish context for literate identity deployment): school, work, family, faith, military, leisure, health

- Statements of belief, values, or attitudes toward literacy, literacy technologies, or aging (whether expressed during or as an aside to life story or literacy tour narration)

With data collected and organized, narrative analysis—the findings of which are represented in the remainder of this essay—was geared toward addressing a central question: How does age identity contribute to individuals’ choices to appropriate, resist, or transform literate identities in later life?

A materially attuned narrative analysis allowed me to consider how participants rhetorically constituted literate identities through language and through their relationships with objects. To begin, I identified all narrative episodes featuring objects. For the purposes of this analysis, objects were defined as non-human, non-living entities either recalled and described or materially displayed during the interview. Participants’ narratives and tours referenced many kinds of real and virtual objects, such as writing tools and technologies (e.g., computers, mobile phones, typewriters, notebooks); reading/viewing tools and technologies (e.g., books, tablets, computers); texts (e.g., websites, maps, photographs); crafted objects (e.g., model vehicles, quilts); collected items (e.g., vinyl records, clocks); and furniture (e.g., chairs, desks). Centering my reading first on the episodes in which objects played a more prominent role, I analyzed these episodes for articulations of values, beliefs, and attitudes that would motivate someone to take up, transform, or reject identity positions that particular literacies offered them. In following narrative episodes that coordinated objects with these statements of attitude, value, and belief across life stages and social domains, I was able to trace how a sense of oneself as being of a certain age reflected and refracted literate identity. In the remainder of this essay, my analysis of participants’ narratives outlines two common ways in which age identity informs and infuses literate identity.

Literacy Tools and Artifacts as Symbols of Generational Identity

Faced with practical inducements to adopting new technological literacy practices in their everyday lives (e.g., the shift of commerce to web-based environments), as well as the cultural changes that serve as consistent reminders of one’s alienation from digital literacy practices (e.g., reports of Twitter activity on televised evening news), all participants felt an obligation to respond by appropriating, resisting, or transforming the literacy practices made not only available, but also seemingly urgent, by the shifting literacyscape. Regardless of the extent to which they engaged with digital culture, these adults were fully aware of its rising social value, corroborating Heidi McKee and Kristine Blair’s finding that the “saturation” of references to digital culture could serve, for the older adults in their 2008 study, as a “jarring reminder of dislocation from . . . important spheres of social, cultural and economic influence in American society” (21). In this historical moment, the very idea of digital devices evoked emotions, values, and identifications for many older adults.

For some participants, encounters with emergent literacy practices and technologies meant maintaining literate identities cultivated earlier in life. Nora (age 86) found that her new tablet extended her literate identity as an “avid reader” despite her weakening eyesight, whereas Grace (69), a once-devoted reader like Nora, found that her growing habit of playing computer games had displaced her reading routine. Louise (70, a retired accountant), Tom (72, a freelance web developer), and Lynda (71, a hospice volunteer and former paralegal) saw the use of computers, social media, and mobile tech in daily life as extensions of their workplace literate identities. For the majority of participants, however, the decision to appropriate or resist digital literacy tools evoked a specific sense of age identity through generational identifications.

As an aspect of age identity, generational identity involves a sense of experiential and ideological affiliation with particular social groups organized by chronological age (e.g., children, teens, adults, old people, elderly people), birth cohort, or other institutionalized generational identities that are not inherently attached to chronological age but that evoke an age-based identity (e.g., junior and senior faculty). Participants in this study regularly expressed literate valuations, attitudes, and beliefs while rhetorically locating themselves along two axes of generational identity: sociohistorical generations—that is, macrosocial divisions among members of a society that are retroactively identified based on birth cohort and historical contexts (e.g., Baby Boomers and Millennials)—and familial generations (Arber and Attias-Donfut).

Sociohistorical Generational Identity: New Tech, Old Age

Although birth dates are poor predictors of individual values and behaviors, sociohistorical generational differentiations are rhetorically powerful identifiers. Most often, participants framed resistance to digital literacies as in keeping with their generation’s values.

Bea (age 86) owned a computer purchased by her late husband, but she preferred using her rotary telephone to communicate, and she relied on her television for news and entertainment. Bea laminated her resistance to a digital literate identity onto a sense of identification with an age cohort: “I’ll be 87 in February. So I don't use [email] as a communication thing, as a rule. I’d rather use the telephone. . . . Older people, we just don’t do computer[s].” She holds firmly within this age-based stance as an expression of generational values rather than as a need to adapt her own practices: “there are many of us that are still keen and interested that are being cut out because I don't know how to retrieve that stuff from on the computer.”

Bea’s sentiments were echoed in other interviews. Steve (age 71), who began his career in clerical work because he could use a typewriter, admitted that the arrival of computers prompted his retreat toward print literacy technologies. Steve recalled that, in the months before he retired, “all these college kids were coming in” knowing, seemingly instinctively, how to use office computers, whereas Steve and his same-age peers “had to learn from scratch”—a perceived generational difference that Steve found “intimidating.” His perception of “digital nativism” (Prensky) marked him as novice in a workplace in which he had developed years of expertise, and this perception contributed to Steve’s decision to retire early and work for a bookstore in order to “be around books.” Carol (age 68), who had recently started freelance work in digital marketing, described her preference for printing out task instructions rather than reading them onscreen: “I’m the one that likes to sit in the chair and read. . . . I guess that’s just my age really speaking.” Similarly, Allan (age 77) marked his preference for the telephone over email as a sign that he was an “ol’ager.”

Of all the possible reasons to claim a preference for reading-based or aural literacies rather than written communication, identification with an older generation was among the most common. Two speculative propositions may explain this tendency. First, in the same way that gender differences of interviewer and interviewee can result in measurably different interview responses (Reinharz and Chase), participants may have felt cued to identify and perform as informants of an older generation in response to a younger interviewer. Second, and even if the first explanation holds true, these consistent age-based assumptions about digital literacies suggest the impact of a curriculum of aging. The above examples illustrate how sociohistorical generational identities and literate identities laminate and co-construct each other, as valuing particular literacy tools and practices is cast as being of a piece with generational values and attitudes on a macrosocial scale: Bea alienates herself from digital literacies (rejecting the literate identities available to her) not only because the computer isn’t useful to her but also because “older people don’t do computers.” In indicating their chronological age or otherwise locating themselves among same-age peers, either as a preface to or instead of a fully developed rationale, many participants claim alienation from new technology as a conscious enactment of age identity: using new technologies is just not what older people do.

Familial Generational Identity: Digital Parenting

In addition to mapping literate identities onto generational values, literate identity and age identity are also laminated onto values associated with family roles and relationships. Social media adoption provides an example: social media users Nora, Georgeanne, Millie, Beverly, Steve, and Patsy all described their appropriation of social media as an extension of their role as a parent or grandparent. For some, including Steve, the use-value of social media was entirely enmeshed with kinship: “I don’t know how to use [Facebook] that much, but I’ll get on it because I have three daughters . . . My oldest daughter, she is on there constantly . . . and so I have to keep checking, you know?” In Steve’s case, a literate identity as a Facebook user is only meaningful insofar as it extends his identity as a father.

For others, appropriation of social media began as enactments of familial identities but ultimately led to opportunities for agentive identity transformation. In Millie’s case, familial identity as a parent was a segue into her social media identity, but her literate identity was quickly laminated onto a sociohistorical generational identity as an “old” woman. The sole surviving parent of a pioneering video blogger in the mid-2000s, Millie cooperated with her son’s plans to create a video series called I Can’t Open It, which reported Millie’s encounters with objects that did not accommodate her aging body (Garfield and Garfield, I Can’t). The video series was a spin-off of sorts from Millie’s text-based blog (originally named My Mom’s Blog, later retitled My Mom’s Blog by Thoroughly Modern Millie), which for thirteen years documented her daily life and recollections (Garfield and Garfield, My Mom’s). Although initiated by her interest in supporting her son’s career, Millie’s appropriation of a digital literacy identity led to a transformation of her age identity through contact with new communities, both online and off, that transformed her expression of familial generational identity (My Mom’s Blog) to a sociohistorical generational identity (Thoroughly Modern Millie). Millie was sought out by journalists, invited to women’s blogging conferences, and celebrated online as an “elderblogger.” Explaining that she was “very proud” of her blogging work, Millie noted that her age was what made her accomplishment noteworthy: “I’ve lived a long time and I feel like I’ve accomplished something very positive. . . . So at my age to have accomplished what I have, I’m proud of [that]. If I was thirty-five, it’s no big deal because they’re all doing it.”

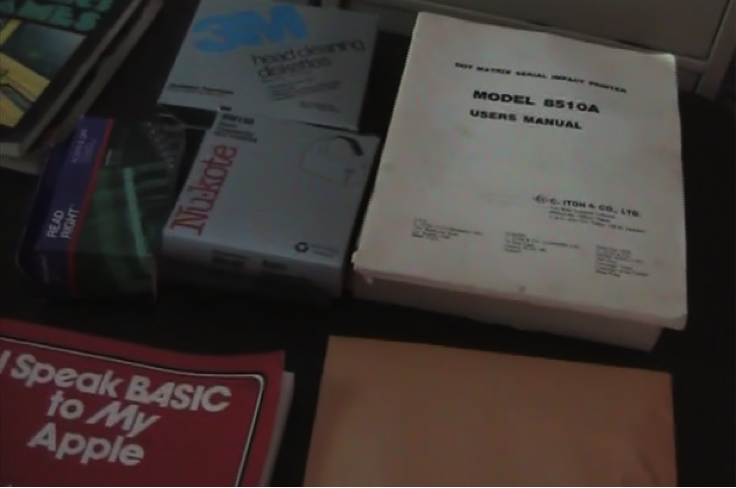

In all cases, the narrated lamination of generational and literate identities was evoked by the actual presence of networked digital devices in the home, as well as the mere awareness that social media practices and technologies existed—and were widely used—in the world. In this final example of generational identity, however, narrative episodes were evoked by an autotopography that illustrates the complex interanimation of literate and age identities. When I arrived to interview Patsy (age 78), she had laid out a collection of decades-old computer accessories and manuals on a folding table (see Figure 1). The objects were the contents of the startup kit for the Apple IIe she had purchased in 1983, which she used for bookkeeping and communication for the two businesses she co-owned with her husband.

Figure 1. Part of Patsy's Apple IIe Archive

Presenting this curated collection, Patsy made it clear that the artifacts had no use-value: “Do you think I read every one of these? [gestures to the manuals on the table] I never read any of them.” These outmoded, unused relics evoked a story not about her own literacy practices, but about the digital expertise of her son Andy, the youngest of her seven children:

I mean all those books, [Andy] probably read them, but I didn’t. There is one of them that says “programming.” . . . I don't know if I mentioned it . . . Andy’s school teacher was a math teacher and, so this is when the schools started to get Commodores, the old computers, and so they had to learn it themselves, reading something. And [the teacher] would be on the [chalk]board doing something and Andy would put his hand up and say, “No, that’s not right.” So, [the teacher said] “Just a minute, Andy,” so he'd send [Andy] to the principal’s office.

Patsy’s tendency to narrate Andy’s digital technology expertise rather than her own continued as the literacy tour proceeded, during which Patsy showed me the thirteen-year-old iMac she occasionally used and the new iPad she used frequently to check Facebook and play mobile video games. All the while, these devices evoked Patsy’s feelings of pride in her son. For example, when I ask her how she acquired her first iPad, she recalled that it was a gift from all of her children but added, “I don’t think Andy was here [when they gave it to me] because naturally I would have relied on him.” Although Patsy has six other children and dozens of grandchildren, she remained committed to upholding Andy’s status as the family’s leading digital expert, an identity she had chosen for him from an early age: “one night, this was [when Andy was in] high school, and I came downstairs and the lights were on, and I thought, ‘What the heck?’ Andy was at the computer at three o’clock in the morning. I mean, he was, right into it then. He’s still the one if there’s a problem, I can’t do something, I call him up.”

As both an early home-computer user wielding emergent technologies to perform complex literacy and numeracy practices and as a business owner, Patsy could have claimed a digital literate identity. However, as evidenced by her autotopography of technological literacy, Patsy’s narrated literate self is displaced by Andy’s. Like Millie, Patsy’s literate identity and her generational identity—across both axes of generational identification—become laminated onto one another. This lamination is traceable in a story she told while showing me her new digital tablet. Patsy begins by claiming a digital literate identity; however, the rhetorical framing of her own expertise is quickly rerouted and sublimated by generational identification: “I learn these as I go along, sometimes by testing. Sometimes I think the older people are afraid to push the button. And Andy said the same thing, you know, ‘My kids have taught me things.’ . . . So the little ones were teaching him.”

In Patsy’s accounting of her relationship to digital literacy technologies, familial generational identities laminate onto her sense of literate identity so inextricably that her own uptake of digital literacy cannot be articulated apart from her role as the parent of a child with a fondness for digital technology. This rhetorical fusion of generational identity and literate identity becomes a lens by which she interprets other multigenerational literacy events, as her expert son Andy, now a parent, is reframed as a learner rather than an expert relative to his own children.

As demonstrated here, attending to the ways in which individuals story their relationships with literacy tools enacts and expands what John Duffy calls a rhetorical conception of literacy: “In a rhetorical conception of literacy, individual acts of reading and writing, of decoding and encoding, have little meaning in themselves. . . . Literacy in this sense is a product of powerfully shaping rhetorics that work to define, inscribe, and organize human activity” (17). Duffy’s rhetorical conception of literacy foregrounds literacy’s social and cultural dimensions: ways of using literacy, and by extension the literate identities individuals might choose to take up, are always partly “defined, inscribed, and organized” by “powerfully shaping rhetorics” (17). Whereas Duffy attends centrally to discursive rhetorics, the work of Ian Bogost, Casey Boyle, and Jody Shipka (among others) urges us to remember that objects, too, do rhetorical work. Patsy and Millie’s cases illustrate particular kinds of objects doing a particular kind of rhetorical work: digital literacy tools operating as material symbols of age-based ideologies and knowledges—as “powerfully shaping rhetorics”—that evoke literate and age identities. The identity work of literacy tools and technologies is easily observable when literacy tools are owned and used (and thus demonstrably valued), but as Bea’s denial of digital literacy for older adults suggests, identity work also occurs in response to the mismatch of personal and cultural values in relation to particular literacy tools and technologies.

Thus, valued or not, digital literacy devices evoke generational identities through which the sedimented ideologies associated with generational roles become folded into literate identity. However, generational identity is not a simple predictor of an individual’s choice to resist, appropriate, or transform literate identities. Millie and Patsy, both ascribing to the belief that older adults generally do not claim digital expertise relative to younger people, provide valuable counterexamples. While Millie’s identity as a mother provides a basis for adopting digital literacy practices, her literate identity (given value by her sociocultural generational identity, as an outlier among her peers) provides grounds upon which she claims and amplifies her identity as elderblogger; inversely, Patsy had already adopted digital literacy practices as part of her role as a business owner in her mid-40s, but later in life her familial identity as a mother and grandmother prompted the rhetorical amplification of her son and grandchildren’s literacies rather than her own.

Narrated Selves across the Lifespan

In addition to the sedimentation of literacy and age ideologies over a lifetime, growing old(er) may occasion recalibration of motives, values, and perspectives that impact all dimensions of life, including literacy. Rhetorical practices of self-narration and memorialization address such exigences of later life. Through the extended example of Bob (age 84), this section illustrates the rhetorical resistance to a new literate identity through a complex web of evocative objects.

A retired paper mill manager, Bob began his literacy tour by quickly distancing himself from a digital literate identity, despite telling me that he used a computer regularly to shop for automobile parts and to watch the stock market five days a week. Standing beside his computer, Bob noted that his adult children and their spouses were “all computer literate” and that “they’ve got the [smart]phones now.” The role of these devices in younger generations’ lives was, for Bob, a “can of worms”:

I am very concerned how many times I go into a restaurant and there’d be two people sitting at a table, and they’ve both got their phones out and neither are talking to each other. The other thing I’m seeing with them is because it’s so easy to take a picture and put it on the phone, which is a form of computer. But, there’s no permanent record. . . . We are losing a lot. We are living in the present, we’re forgetting the past, and I’m afraid for the future.

For Bob, the remediation of interpersonal communication and photography via smartphone technologies held serious social consequences for all generations. To further illustrate his lament, Bob led me to a wall-mounted map of the contiguous United States, to which Bob and his late wife had affixed labels and highlighted routes, documenting years of cross-country road trips. Standing next to the map, Bob described how much he valued meeting fellow travelers and hosting picnic-style meals out of vehicles, thus recalling his earlier complaint about mobile phones in restaurants. He explained that “eating over a table . . . that’s fundamental to your life, and if you can do this with somebody else and be able to talk at the same time, do things—I’m getting to be a philosopher now, but you know, I just think that so much is missing when you can’t do it.”

Using the map as a form of inartistic proof, Bob testifies to the value of memory-making and human connection, which he fears is lost to future generations as an outcome of networked digital communication. Bob’s recruitment of curated objects in his self-narration presents an occasion in which to further theorize material memory work as rhetorical practice. In her study of one woman’s personal archives and diaries generated at the turn of the twentieth century, Liz Rohan proposes memory as a material rhetorical practice, as “craft,” involving the collection, curation, and arrangement of materials. The rhetorical canon of memory is, for Rohan, both a means and ends of persuasion. Rohan claims that the woman whose archives she is studying, Janette, “doesn’t remember so that she can create rhetoric but rather creates rhetoric and corresponding mnemonic crafts so she might remember” (373). Moreover, curated objects do more than serve as mnemonic devices: they also preserve values, including those under threat of erosion. Bob, like Janette, responds to personal and cultural fears about the potential loss of both memories and values by curating objects.

However, Bob’s fear of lost values and the need for nostalgic memory-work may be further amplified by his subjective awareness of advancing age. Bob mourns the digital remediation of embodied experiences (e.g., sharing meals) and durable memory aids (e.g., printed photographs) that help him, as an older adult, memorialize the identities—manager, tourist, husband—that are no longer available to him as a retiree and widower. Old age, for Bob, is a rhetorical situation. Jerome Bruner describes the constitution of self through narrative in situated, rhetorical terms, as individuals “constantly construct and reconstruct ourselves to meet the needs of the situations we encounter” (Making Stories 64). In his own old age, Bruner proposed that the “willingness or eagerness to ‘story’ one’s life” takes on new significance near life’s end. The maintenance of a sense of narrative tension—a sense of what is left unfinished—creates a subjective sense of distance from death; further, the meaningfulness of a long life is dependent in part on “the sense of the past providing some basis for the present being as it is” (“Narratives” 9). Bob’s case favors Bruner’s sense of the difference old age makes to the motives for narrative identifications. Late life may present a particular kind of rhetorical exigence in that aged rhetors like Bob may feel the need to maintain a sense of “incompleteness” and tension (work yet to be done, serving as a wise elder) while also forging a sense of coherence with prior life experiences (thus casting his story as the marker of consistent, if endangered, values).

And yet, Bob is not the sole author of his own life story. Bob’s use of objects in his home to privilege anti-digital values has dual effects: creating the coherent “myth” of Bob as wise elder while also exposing inconsistencies inherent in that narrative. A further example will illustrate this contradiction. At a later point in his tour, Bob pointed to a display case of model tractors on top of his kitchen cabinets and noted that he owned a full-size antique tractor as part of his collection of antique vehicles (see Figure 2). As with the road map, Bob used the tractor and his off-site car collection as symbols of his resistance to digital literacies. Explaining his reluctance to purchase vehicle parts for his cars online, Bob interrupted his account to ask if I’d heard of the Luddites. A loosely organized group of textile workers in early-nineteenth-century England, Luddites were famously known for smashing cotton and wool machines, which threatened their wages by reducing need for human laborers. Although “Luddite” is currently used to disparage those who stubbornly resist technological progress, Bob embraced the original ideological stance of the Luddites, substituting twenty-first-century computers for the “obnoxious” machines of the nineteenth century (Binfield 3).

Figure 2. Bob’s Model Tractors

Beginning first by reminding me of his age—“I’m 84 years old”—Bob fondly described an industrial past: “I can remember when they were building cars. . . . There were men welding bodies together and there were all these men lined up. And they were working hard, but they were making an honest living, and the wages were good. It was good.” Within the same narrative, he also recalled an agrarian past: “Used to be a man could make a living with thirty cows.” In contrast to this nostalgic reminiscence (though not of his own direct experience), Bob leaned into his Luddite identity. Using his car collection and model tractors as synecdochal stand-ins for automakers and farmers, Bob declared: “As far as I’m concerned, it’s gone too far. . . . [I]t’s gone to the point where it is replacing people to the detriment of, I believe, society as a whole.” As evoked by his autotopography, Bob’s man-versus-machine narrative encapsulates the complex sedimentation of values accrued over a lifetime, which in turn shape the literate and age identities he will (or will not) willingly take up.

Yet, these same objects evoke—for me, as immediate audience of Bob’s narrative and literacy tour—the conflicts among his various narrated and enacted selves. At one point in his life story interview, Bob described himself as a “farm boy” who was “always interested in machinery,” beginning at age twelve when he operated horse-drawn mowing machines on a neighbor’s farm. Such farm equipment was obsolescent, as tractors had emerged decades prior and had already begun displacing human laborers (Ganzel). Ironically, these tractors, including the one Bob treasured as part of his collection of antique vehicles, dramatically reduced the number of farm workers necessary for mowing and plowing, much as cotton and wool machines had done to textile workers in Edwardian England. Furthering the irony, Bob’s passion for machines led him to join the first graduating class of the pulp and paper management program and to a long career that culminated in his role as chief engineer and manager of a hundred-year-old paper mill, which shut down soon after Bob retired. While his career as an engineer was propitious and lucrative, Bob’s financial success was due in large part to stock investments, which he monitored every weekday on his computer.

Bob’s rhetorical rejection of digital literacies in the interview extends beyond generational identifications. He does not claim to be an “ol’ager,” but rather a wise Luddite elder with a view of social values lost to technological progress. Through an object-evoked autobiography from a late-life standpoint (“I’m 84. I can remember when . . .”), Bob achieves a sense of narrative coherence in characterizing his present Luddite self using experience to warn younger generations; yet, the objects recruited into this narrative speak to unacknowledged tensions among his laminated identities as Luddite hero, capitalist, and industrial technophile.

Conclusion: Ag(e)ing Identity

Through the materially attuned methodological practice of eliciting and interpreting life stories and literacy tours, this essay has taken up the central question: How does age identity contribute to individuals’ choices to appropriate, resist, or transform literate identities in later life? Findings of the study suggest two broad answers to this question. First, generational age identifications are a common framework for individuals’ decisions to take up new literacies, particularly those involving new technologies. Participants’ consistent recognition that digital technologies represent age-based identities and ideologies evidences the impact of a curriculum of aging on the literate identities that individuals see available to them at any given point in life. Second, late life may present a particular kind of rhetorical exigence, which similarly shapes the perceived availability of literate identity in later life. As Bob’s case illustrates, the impulse to construct a cohesive, socially relevant identity might provide a new rhetorical motive for appropriating, resisting, or transforming literate identities.

While the interanimation of age identity and literate identity may be traceable to a certain extent through discursive narration—the sole object of study in traditional life story research—the rhetorical ecologies of new materialism highlights the lamination of (and tensions among) identities. Although the methodology here remains decidedly human-centered, the rhetorical practice of “storying a life” is acknowledged as distributed among humans and objects: Bea and her rotary phone, Patsy and her Apple IIe archive, Millie and her son’s video camera, Bob and his road map. Memories, emotion, story, and identity are narratively constituted in the material and symbolic relationships between human and non-human. As such, this study stands as a demonstration of the value of materialist rhetorical methodologies for research into the rhetorical practices of identification.

Finally, and most significantly, this study evidences the value of age identity as an analytical frame in writing studies research across the lifespan. Constituted with or against the curriculum of aging, which forwards dominant ideas about how to be a person of a particular age, age identity contributes to individuals’ literate identities by cultivating a sense of what is appropriate and desirable—a sense of how to “act your age” through literacy practices. Although individuals are inevitably exposed to a curriculum of aging that models dominant age-based identity kits, they make agentive choices about whether (and how) to take up those modeled age identities. Millie, for example, knew all too well that blogging was not something people her age usually did, but the chance to defy convention was, for her, a source of motivation for digital literacy practices.

The rhetorical constitution of literate identity, however, is not always in keeping with actual literate practice. Recall that Bob and Patsy, although both engaged regularly with digital literacy practices, rhetorically resisted or deflected outright claims of a digital literate identity as they constituted narrative selves in the interview scene. Regardless of the presence and practical use-value of literacies in everyday life, the rhetorical constitution of a literate identity can be constrained by the gravitational pull of age identity already contributes to narratives individuals tell about themselves: different phases of the lifespan yield different purposes and outcomes for narrating the self. In later life, as Bob illustrates, the rhetorical motive to construct whole, yet simultaneously unfinished, narratives of the self becomes bound up in other adulthood values, such as feeling the need to impart wisdom on younger generations to ensure their brighter futures—and in literate valuation—such as the need to appropriate or to rhetorically resist digital literacy practices.

Literate identity, too, becomes an important resource for the agentive constitution of desirable age identities, as can be seen in Millie’s stereotype-defying expressions of age identity, as coordinated through complex literate activity. However, the availability of literate and age identities—and the resources individuals have for constituting them—are dependent upon the complex configurations of other dimensions of identity. The lamination of identities and sedimentation of emplaced dispositions and orientations, accrued over a lifespan, afford and constrain age identity and literate identity.

In carrying forward dual interests in identity and a lifespan view of literacy, writing studies researchers might forge new theoretical ground through age identity. I close, then, with an invitation to take up age identity theory, and I offer three potential points of departure for further study.

- Not emphasized in this study, the biological or bodily aspects of aging are relevant to the constitution of age identity. What, then, might aging bodies tell us about the interanimation of literate identity and age identity? How might bodily aging motivate, as well as render difficult (perhaps even impossible), particular engagements with literacy?

- In the same way literate identities are constituted even when we are not actively reading and writing, age identities are constituted even when we are not (yet) old. How might age identity impact literacy practice and literate identity at earlier stages in the lifespan? How might the curriculum of aging cultivate normative ideas about aging and literacy even in youth and early adulthood? How might ways of narrating the self change over a lifespan?

- Given the importance of objects and space for the constitution of literate and age identity, what might we learn about the literate identities of late-life writers who, unlike the participants of this study, have reduced autonomy over their own space? Or those who no longer have physical access to autotopographies when forced by financial and/or health to leave familiar home places? Or those whose home places are otherwise unstable?

As the field continues its important work of considering identity not as a fixed set of discrete categories but as a verb, rhetorically constituted through “dynamic, relational, and emergent” differences (Kerschbaum 56), and as it turns its view toward literacy from the long view of a lifespan, the ubiquity of age—like gender, race/ethnicity, and ability—becomes harder to ignore.

Alexis, Cydney. “The Material Culture of Writing: Objects, Habitats, and Identities in Practice.” Rhetoric, Through Everyday Things, edited by Scot Barnett and Casey Boyle, U of Alabama P, 2016, pp. 83–95.

---. “The Symbolic Life of the Moleskine Notebook: Material Goods as a Tableau for Writing Identity Performance.” Composition Studies, vol. 45, no. 2, 2017, pp. 32–54.

Arber, Sara, and Claudine Attias-Donfut. The Myth of Generational Conflict: The Family and State in Ageing Societies. Routledge, 2002.

Atkinson, Robert. The Life Story Interview. SAGE, 1998.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Edited by Michael Holquist, translated by Caryl Emerson, U of Texas P, 1983.

Banks, Adam J. Race, Rhetoric, and Technology: Searching for Higher Ground. Lawrence Erlbaum, 2006.

Barton, David. Literacy: An Introduction to the Ecology of Written Language. 2nd ed., Wiley-Blackwell, 2007.

Bateson, Mary Catherine. Composing a Further Life: The Age of Active Wisdom. Knopf, 2010.

Bazerman, Charles, et al., editors. The Lifespan Development of Writing. National Council of Teachers of English, 2018.

Beauvoir, Simone de. The Coming of Age. Norton, 1996.

Bertaux, Daniel, and Martin Kohli. “The Life Story Approach: A Continental View.” Annual Review of Sociology, vol. 10, 1984, pp. 215–37.

Binfield, Kevin. Writings of the Luddites. Johns Hopkins UP, 2015.

Bogost, Ian. Alien Phenomenology, or What It’s Like to Be a Thing. U of Minnesota P, 2012.

Bowen, Lauren Marshall. “Beyond Repair: Literacy, Technology, and a Curriculum of Aging.” College English, vol. 74, no. 5, 2012, pp. 437-457.

---. “Literacy Tours and Material Matters: Principles for Studying the Literate Lives of Older Adults.” Dippre and Phillips, WAC Clearinghouse/UP of Colorado, in press.

Boyle, Casey. Rhetoric as a Posthuman Practice. Ohio State UP, 2018.

Brandt, Deborah. Literacy in American Lives. Cambridge UP, 2001.

Bruner, Jerome. “Narratives of Aging.” Journal of Aging Studies, vol. 13, no. 1, 1999, pp. 7–9.

---. Making Stories: Law, Literature, Life. Harvard UP, 2002.

Ching, Kory Lawson. “Tools Matter: Mediated Writing Activity in Alternative Digital Environments.” Written Communication, vol. 35, no. 3, 2018, pp. 344–75.

Crow, Angela. Aging Literacies: Training And Development Challenges for Faculty. Hampton, 2006.

Dippre, Ryan J. “Faith, Squirrels, and Artwork: The Expansive Agency of Textual Coordination in the Literate Action of Older Writers.” Literacy in Composition Studies, vol. 6, no. 2, 2018, pp. 76–93.

Dippre, Ryan J., and Talinn Phillips, editors. Approaches to Lifespan Writing Research: Generating Murmurations Towards and Actionable Coherence. WAC Clearinghouse/UP of Colorado, in press.

Duffy, John. Writing from these Roots: Literacy in a Hmong-American Community. U of Hawai’i P, 2007.

Galambos, Nancy L., et al. “Chronological and Subjective Age in Emerging Adulthood: The Crossover Effect.” Journal of Adolescent Research, vol. 20, no. 5, 2005, pp. 538–56.

Ganzel, Bill. “Walter Ballard on Being ‘Tractored Out.’” Wessels Living History Farm, 2003, https://livinghistoryfarm.org/farminginthe30s/movies/ballard_water_13.html.

Garfield, Millie, and Steve Garfield. I Can’t Open It, http://icantopenit.blogspot.com.

—-. My Mom’s Blog by Thoroughly Modern Millie, http://mymomsblog.blogspot.com.

Gee, James Paul. “Identity as an Analytic Lens for Research in Education.” Review of Research in Education, vol. 25, 2000, pp. 99–125.

---. “Literacy, Discourse, and Linguistics: Introduction.” Journal of Education, vol. 171, no. 1, 1989, pp. 5–176.

González, Jennifer A. “Autotopographies.” Prosthetic Territories, Politics, and Hypertechnologies, edited by Gabriel Brahm Jr. and Mark Driscoll, Westview, 1995, pp. 133–49.

Gries, Laurie. “Agential Matters: Tumbleweed, Women-Pens, Citizens-Hope, and Rhetorical Actancy.” Ecology, Writing Theory, and New Media, edited by Sidney I. Dobrin, Routledge, 2011, pp. 67–91.

Heath, Shirley Brice. Ways with Words: Language, Life and Work in Communities and Classrooms. Cambridge UP, 1983.

Inoue, Asao B. “How Do We Language So People Stop Killing Each Other, Or What Do We Do About White Language Supremacy?” Performance-Rhetoric, Performance-Composition, Conference on College Composition and Communication, 14 March 2019, David L. Lawrence Convention Center, Pittsburgh, PA. Chair’s Address.

Ivanič, Roz. Writing and Identity: The Discoursal Construction of Identity in Academic Writing. John Benjamins, 1998.

Kerschbaum, Stephanie L. Toward a New Rhetoric of Difference. National Council of Teachers of English, 2014.

Leander, Kevin M. “Writing Travelers’ Tales on New Literacyscapes.” Reading Research Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 3, 2003, pp. 392–97.

Lewis, Cynthia, and Antillana Del Valle. “Literacy and Identity: Implications for Research and Practice.” Handbook of Adolescent Literacy Research, edited by Leila Christenbury et al., Guilford, 2008, pp. 307–22.

Lorimer Leonard, Rebecca. Writing on the Move: Migrant Women and the Value of Literacy. U of Pittsburgh P, 2017.

McKee, Heidi, and Kristine Blair. “Older Adults and Community-Based Technological Literacy Programs: Barriers & Benefits to Learning.” Community Literacy Journal, vol. 1, no. 2, 2008, pp. 13–39.

Micciche, Laura R. “Writing Material.” College English, vol. 76, no. 6, 2014, pp. 488–505.

Moje, Elizabeth Birr, and Allan Luke. “Literacy and Identity: Examining the Metaphors in History and Contemporary Research.” Reading Research Quarterly, vol. 44, no. 4, 2009, pp. 415–37.

Pew Research Center. “Demographics of Social Media Users and Adoption in the United States.” Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/.

Porter, Jim. “Why Technology Matters to Writing: A Cyberwriter’s Tale.” Computers and Composition, vol. 20, no. 4, 2003, pp. 375–94.

Prensky, Marc. “Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants Part 1.” On the Horizon, vol. 9, no. 5, 2001, pp. 1–6.

Prior, Paul. Writing/Disciplinarity: A Sociohistoric Account of Literate Activity in the Academy. Lawrence Erlbaum, 1998.

Reinharz, Shulamit, and Susan E. Chase. “Interviewing Women.” Handbook of Interview Research: Context and Method, edited by Jaber F. Gubrium and James A Holstein, Sage, 2002, pp. 221–38.

Rohan, Liz. “I Remember Mamma: Material Rhetoric, Mnemonic Activity, and One Woman’s Turn-of-the-Twentieth-Century Quilt.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 23, no. 4, 2004, pp. 368–87.

Roozen, Kevin. “From Journals to Journalism: Tracing Trajectories of Literate Development.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 60, no. 3, 2009, pp. 541–72.

Roozen, Kevin, and Joe Erickson. Expanding Literate Landscapes: Persons, Practices, and Sociohistoric Perspectives of Disciplinary Development. Computers and Composition Digital P/Utah State UP, 2017.

Rule, Hannah J. “Writing’s Rooms.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 69, no. 3, Feb. 2018, pp. 402–32.

Rumsey, Suzanne Kesler. “Heritage Literacy: Adoption, Adaptation, and Alienation of Multimodal Literacy Tools.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 60, no. 3, 2009, pp. 573–86.

---. “Holding on to Literacies: Older Adult Narratives of Literacy and Agency.” Literacy in Composition Studies, vol. 6, no. 1, 2018, pp. 81–104.

Selfe, Cynthia, and Gail E. Hawisher. Literate Lives in the Information Age: Narratives of Literacy from the United States. Lawrence Erlbaum, 2004.

Shipka, Jody. Toward a Composition Made Whole. U of Pittsburgh P, 2011.

Street, Brian V. Literacy in Theory and Practice. Cambridge UP, 1984.

Turkle, Sherry, editor. Evocative Objects: Things We Think With. MIT Press, 2007.

Vee, Annette. “Understanding Computer Programming as a Literacy.” Literacy in Composition Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, 2013, pp. 42–64.

WPA-L Working Group and nextGEN. “Dialogue and Disciplinary Space.” Composition Studies, vol. 47, no. 2, 2019.