ICONOSTASIS

milieu

esprit

chair

fusion

caractère

offre

outil

CONTEXT

MOTIVATION

CONTENT

SYNCRESIS

OUTPUT

RESPONSE

METHOD

CONTEXT 1

CYBER-HISTORY

The prefix “cyber-” comes to contemporary usage through Norbert Weiner’s* “cybernetics,” the study and creation of self-guiding systems. Weiner chose the Greek root kyberne- (used in the words kybernân, “to steer,” and kybernet, “helmsman,” which serve as the roots for the English word “government”).* When looked at in terms of this etymology, “cyber-history” indicates a form of research that uses history as a guide. Though the use of precedents in contemporary problem solving has always been part of historiography, this application of research is generally excised from historiographical techniques and methods. The field of history (the collection of institutions, techniques, and practitioners that effect and study history) does not regularly concern itself with how the results of its discourse are used in the production of new things.

Notes

* Wiener, Norbert. Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. MIT Press, 1961.

CONTEXT 2

APPLIED HEURETICS

Cyber-history is proposed as a supplemental location for exploring techniques that use historical material in the production of new ways of making, or in other words, the production of new methods. As such, cyber-history is applied heuretics.

In the seventeenth century the theologian Richard Burthogge wrote, “Ratiocination Speculative, is either Euretick or Hermeneutick, Inventive or Interpretive” (48).† Here, Burthogge posits the definition of hermeneutics as the logic of interpretation and at the same time posits its counterpart, “euretick,” as the logic of invention. While hermeneutics has grown into a rich field of research on the nature of interpretation, its role in the production of meaning, and its relationship to rhetoric, euretics as the study of invention has been neglected, and its native logic and relation to rhetoric remains obscure.

Greg Ulmer has spent decades developing heuretics and exploring its role in digital rhetoric as a supplement to hermeneutics. Hermeneutics emerged from writing technology, providing a logic for the relationship between intellection and textual media discourse. Ulmer proposes that heuretics can provide a logic for digital and multi-modal media: invention can be articulated in any medium. While hermeneutics facilitates the construction of new theories from discrete pieces of information through processes of interpretation, heuretics, as the logic of invention, uses existing theories to facilitate the production of new methods.

One of the tools from Ulmer’s work that is useful in the formation of techniques for cyber-history is the CATTt Generator. The CATTt Generator allows us to simulate our inventio, or the work the brain performs before and during invention of new material. Our brains are constantly producing new methods that we test and use to navigate our daily lives. Thinking of a safe way to walk on an icy patch of sidewalk in our new shoes or figuring out how to open the front door with hands full of groceries are examples of quotidian method production. The CATTt Generator gives us a way to simulate the complex chemical and physical processes our brains perform for invention so that we can jump-start, fine-tune, and better communicate them. To identify the materials needed to adequately simulate inventio, Ulmer studied the ways several authors discussed method; this study led him to identify five common components, which he then articulated as a new method:

[C]ontrast: a desired divergence from a known discourse, field, or method. The inventor must begin by moving away from an undesirable example whose features provide an inventory of components made valuable through determining their exterior.

[A]nalogy: a discourse or method from some other field that offers a model for a successful way of working. The sought for method does not currently exist, so the inventor must study something similar that serves as a relay of knowledge between separate domains.

[T]heory: a rigorously developed methodology from the creator’s working discipline used primarily to offer weight and substance to the new creation: “[T]he theorist generates a new theory based on the authority of another theory whose argument is accepted as a literal rather than a figurative analogy. The new theory will include in one register a literal repetition of a prior theory” (9).‡

[T]arget: the intended audience. The inventor must have an intended area of application that the new method will address, frequently identifiable in terms of the needs of an institution that desires the new method.

[t]ale/[t]ail: a final presentation format. The tale/tail exists to remind the inventor “that the invention, the new method, must itself be represented in some form or genre” (9).‡

The inventor decides what the input for each component will be, researches each of them to ensure a sufficiently accurate representation of the input, and runs the experiment to produce the method, which is made communicable through the decided format. If the method experiment does not produce the needed results, the inputs can be adjusted, resulting in another method experiment. The process repeats until the desired outcome is achieved or something better is found.

While we can use the CATTt Generator for producing methods, we can also use it to analyze existing methods by articulating historical precedents as method experiments. This method of analysis is particularly useful in architecture and design research because practicing architects and design teachers constantly make use of history by pulling bits of material from existing buildings and objects. This gleaning is not historiographical or archival in nature—designers are not attempting to document the precedents that inform their work through design; rather, they want to use precedents to make new things.

Heuretics is also particularly applicable to architectural discourse because architecture is inherently multi-modal; we write and speak about architecture, but the buildings themselves do not engage directly in discourse. While buildings seem mute, they certainly affect us, and they communicate through material, light, the sound and shape of their spaces, etc; this communication precedes anything we might say or write about them to evaluate or convey meaning. When a designer engages a new and complex project or a design problem, the first step is to propose a method for navigating all the material and possible processes that inform the situation; there is no single way of producing design solutions for infinite possible design prompts or for determining how complex programs will be accommodated by a building on a specific and unique site. To begin working a designer must cobble together a method from diverse inputs or at least adapt an existing method to the specific new project.

Notes

† Burthogge, Richard. “Organum Vetus et Novum, or a Discourse of Reason and Truth.” The Philosophical Writings of Richard Burthogge, edited by Margaret Winifred Langes, The Open Court Publishing Company, 1921.

‡ Ulmer, Gregory. Heuretics: The Logic of Invention. John Hopkins UP, 1994.

CONTEXT 3

My first application of heuretics to historical analysis is focused on the work and legacy of the architect Le Corbusier (1887-1965). One of the founders of modernism, Le Corbusier designed hundreds of buildings (more than seventy of which were built), published forty-seven books (not including monographs of his oeuvre), authored numerous articles, designed furnishings and exhibits, and prolifically painted under his given name Charles-Édouard Jeanneret. This personal oeuvre, in addition to the hundreds of publications written about his life and work, make Le Corbusier one of the most recognizable figures in the history of architecture, even amongst non-architects. And, like the other members of his early twentieth-century avant-garde milieu, Le Corbusier was constantly engaging in method experiments.

CONTEXT 4

The modernists in particular were attempting to engage new media and physical materials to produce new ways of working that could not be found in any historical precedents. Greek temples, gothic cathedrals, and other monuments from the vast material history of human culture can offer lessons in line and form, light and shadow, and guide us in the use of traditional materials such as stone, timber, brick, and earth, but they can directly indicate to us little of how to use steel, large panes of glass, and reinforced concrete to make buildings. When these industrial materials became widely available for construction in the late nineteenth century, completely new possibilities were opened for how architects and engineers could conceive of space and structure, but no one had an extant way of working to apply these possibilities to design and construction. Methodological experiments were needed to test new design languages appropriate for industrial materials. Modern-ism, like any “ism,” is not a style; it is a way of working/making—a way of making modernity. Modernism is a method. Each work produced by the early twentieth-century avant-gardes in every medium upon which industrial technologies effected change exists as more than just a completed object: it is the index and direct result of a methodological experiment. Evaluating these works as objects misses so much of their usefulness and so much of the value they embody for posterity.

CONTEXT 5

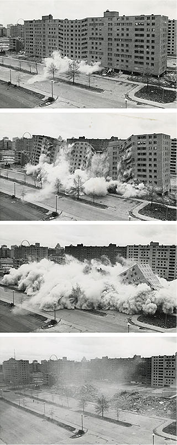

There is a discrepancy in Le Corbusier’s legacy that divides many of his smaller scale projects, like the Villa Savoye and other platonic villas of the 1920s, from his large-scale urban proposals. Today, architects still use Le Corbusier’s buildings as valuable precedents; the buildings embody a formal language and set of techniques that remain current for designers around the world, and their visual legibility has grown more wide-spread in the several decades since the international diffusion of modernism. This popularity contrasts completely with the legacy of Le Corbusier’s urban planning. Le Corbusier thought of his proposed modernism as a method that could be applied to ways of making at any scale from small objects like books and furnishings, to buildings, to entire cities and larger metropolitan regions. This general applicability of his method proposals was necessary because industrialization had brought new technologies and materials that had profound implications affecting humans and their world at every scale. But Le Corbusier’s modern urbanisms were so reviled in the late 60s and 70s that they were used as a primary point of contrast for the development of post-modernism. By the early 80s, the modernist city was widely regarded as a failure amongst urban planners and architecture critics, who used its shortcomings to construct grounds for the failure of modern architecture as a whole through a form of ritualistic killing:

Modern Architecture died in St. Louis, Missouri on July 15, 1972 at 3:32 pm (or thereabouts) when the infamous Pruitt-Igoe scheme, or rather several of its slab blocks were given the final coup de grâce by dynamite. ||

In this quote from Charles Jencks, the demolition of the Pruitt-Igoe Housing Complex was used to support the case to move away from architectural modernism. But, this support is gained through the formal similarity linking failed government housing projects to the modernist urban proposals of the early-twentieth century; the fact that Cabrini Green and Pruitt-Igoe looked a great deal like Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse and that all were consciously identified as modernist certainly seems persuasive when evaluating these cases as objects, but this formal similarity obscures the gulf that separates infamous government housing projects around the world from Le Corbusier’s modernisms when the cases are examined in terms of the methodologies that produced them and the more specific results of their production. Formal similarities reveal very little in the comparison of how separate projects are made, the various stakeholders who influence their production, how they are funded, and how inhabitants use them.

Notes

§ U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Pruitt-igoe Collapse Series. 1972. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pruitt-igoe_collapse-series.jpg

|| Jenks, Charles. The Language of Post-modern Architecture. Rizzoli International Publications, 1981.

MOTIVATION 1

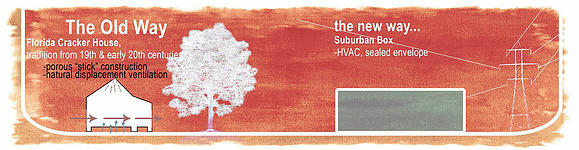

The early test of cyber-history was to see if the results of CATTt analysis in elucidating methods could in turn be used to produce new methods to address a contemporary issue or solve a problem. I had for several years been searching for a way to design low energy housing for my local environment of North Central Florida that would also be low cost. North Central Florida is very hot and humid for most of the year, with the hottest months also experiencing little wind, making it difficult to remain comfortable in interior spaces without extensive use of HVAC systems. The typical solution is something I call the Total Recall strategy, named after the 1990 Paul Verhoeven film version of the Philip K. Dick story “We Can Remember It For You Wholesale,” which depicts a human colony living on Mars through the use of a complete separation of interior inhabitable spaces from the poisonous atmosphere outside. In the southern U.S., we insulate to isolate the interior from the exterior as completely as possible; then, we pump the interior full of energy in the form of cold (or warm) air to produce a comfortable environment. This strategy has only been available to the general public for home use since the 1960s, when HVAC technologies and products became inexpensive enough for inclusion in the average single family home.

Before the 1960s, anyone attempting to be comfortable indoors in the South had to use the opposite strategy: open the interior as much as possible to the exterior through operable and porous assemblies to catch any available cross winds. Some vernacular building types also featured a “hot tin roof” and a crawlspace to create displacement ventilation: the metal roof heats rapidly in the sun in turn heating the air in the space directly underneath, while a vent at the peak of the roof allows the rising hot air to escape, creating a vacuum inside the building; shaded, cooler air from the crawlspace under the house is sucked upward through a highly porous wood floor, effectively producing a cool breeze inside the house even in the complete absence of natural wind currents outside. A famous example of these traditional techniques used to construct housing in Florida is the Florida Cracker House, named after the English and American settlers who came to the area after Spain traded it to Great Britain.

The design problem emerges from the mutually exclusive nature of traditional Cracker techniques (emphasizing porosity) and contemporary environmental technologies (requiring insulation): can a building successfully utilize both energy strategies? If a design method could use both strategies, then the benefits of both inexpensive passive systems and the easy comfort and humidity mitigation of efficient HVAC systems could be obtained. But questions do not stop there. Once formulated, how could such a method be effectively propagated to reach practitioners and the general public so that they might use it for production? Answering these questions was an opportunity to test cyber-history techniques.

MOTIVATION 2

To see if cyber-history and CATTt analysis were useful in articulating method experiments that could be applied to contemporary issues to help generate new methods, I decided to analyze an example method experiment from Le Corbusier’s career to inform a way of working on and presenting my ongoing design research. The first step was to choose a method experiment that was pertinent to my own current tasks, so that the materials contained in both the CATTt Generator inputs and outputs correspond fairly closely with relevant inputs for my own experiment, allowing the analytical process to serve as a guide for contemporary efforts. One experiment that met the criteria was Le Corbusier’s “Five Points Towards a New Architecture,” conceived alongside his longtime collaborative partner and cousin Pierre Jeanneret in 1926.

The Five Points was a wildly popular and influential presentation of Le Corbusier’s architectural modernism. The most persuasive aspect of this experiment was its format: five simple tenets that are easy to remember but summarize the directives and possibilities of a new and appropriate way of working with industrial materials in architectural applications. The Five Points are:

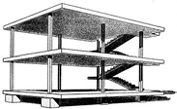

1 - The supports, or separation of load-bearing from non-load-bearing elements;

2 – The roof gardens, obtained through use of flat roofs;

3 – The free designing of the ground-plan (obtained through point number one): the walls and partitions don’t need to supply structural support and thus can take any form and be made of any material;

4 – The horizontal window (also a product of point one): the exterior walls do not need to bear any loads, so windows can and should stretch across their whole length where view and lighting are desired;

5 – Free design of the facade, which does not bear loads and can thus take any form or material to best match and articulate the free-plan. ◊

Given the popularity and effectiveness of the Five Points, the format was appropriate to my own method experiment, validating exploration of the other CATTt components that went into its production.

Notes

Δ McGuirk, Justin. “The Perfect Architectural Symbol for an Era Obsessed with Customization and Participation,” Dezeen.com, https://static.dezeen.com/uploads/2014/03/Le-Corbusier-Do-mino-diagram_dezeen_2.jpg

◊ Le Corbusier and P. Jeanneret. “Towards a New Architecture: Guiding Principles.” Programs and Manifestos on 20th Century Architecture, edited by Ulrich Conrads, MIT Press, 1971, pp. 99-101.

MOTIVATION 3

Through close reading of Le Corbusier’s publications that explore his proposed architectural modernism preceding the appearance of the Five Points in 1926 (many of which are conveniently collected in his popular book Towards a New Architecture **), the first results of CATTt analysis reveal a common issue with this application of heuretics and the CATTt Generator components as an analytical tool: instances of historical method invention will usually feature more than the five necessary CATTt component inputs: the inventor will have attempted to use (and document) many inputs for each component of the CATTt. This messiness underscores the need for Ulmer’s search for common material in method production in order to simulate inventio: the processes of invention are obscure and thus haphazard, calling for a set of tools and techniques—a rhetoric—to serve as our guide to navigate them more effectively. These circumstances result in our need to sift through multiple CATTt inputs to best formulate the operative material in any precedent method experiment. The inputs are thus debatable. With this in mind, I propose one possible CATTt Generator input-set for the Five Points of Towards A New Architecture to be:

[C]ontrast: Beaux Arts classicism

[A]nalogy: Machine Aesthetic—form following function in engineering

[T]heory: traditional vernacular forms

[T]arget: architects and architecture students

tale/tail: The Five Points

Notes

** Le Corbusier. Towards a New Architecture. 1923. Translated by Frederick Etchells. Martino Fine Books, 2014.

CONTENT

ADAPTING THE CATTt COMPONENTS TO THE NEW EXPERIMENT

The next step in the validation of cyber-history was to adapt the precedent method experiment and its CATTt inputs to a new experiment, making changes to the material where needed but preserving as much from each component as possible. Nearly one hundred years had passed between Le Corbusier’s invention of the Five Points and my own method experimentation, and the field of architecture had gone through considerable change; thus, some of the components needed updating:

1

[C]ontrast- Solar Decathlon. While affordability has become more of a priority in the past several years, the early editions of this low-energy housing typology competition were more focused on pushing design and technology to the limits of energy efficiency and energy production within the single family home, with little concern for cost or applicability to today’s housing markets. My own low-energy design method could take the opposite approach, not seeking the limits of what is currently possible but merely attempting to provide working-class clients with low energy options, using construction techniques, technologies, and products already available in the housing market.

2&3

[A]nalogy- Because the Five Points and Corbu’s modernisms in general were so effective, his trademark analogies have become common vocabulary in architecture over the past century. Form following function is no longer an analogy; it’s our [T]heory. So this shifts our [A]nalogy to aspects of design that are currently neglected or pushed to the margins of contemporary architectural discourse. In developing his form/function analogy, Corbu analyzed various traditional building types. So we flip these two components: traditional building types become our [A]nalogy and form following function becomes our [T]heory.

4

[T]arget- Architects (students in particular) and locals (instead of the international character of Corbu’s modernism.)

5

t- The Five Points

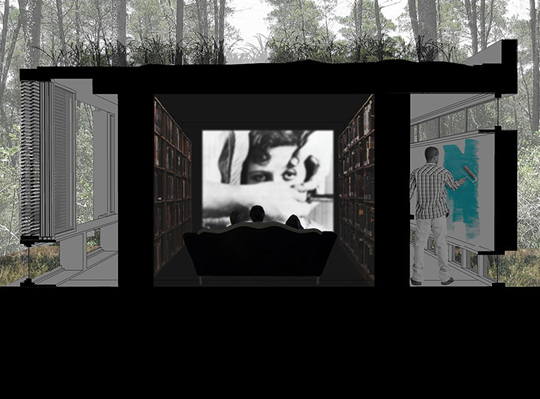

SYNCRESIS

SPECTACULAR VERNACULAR

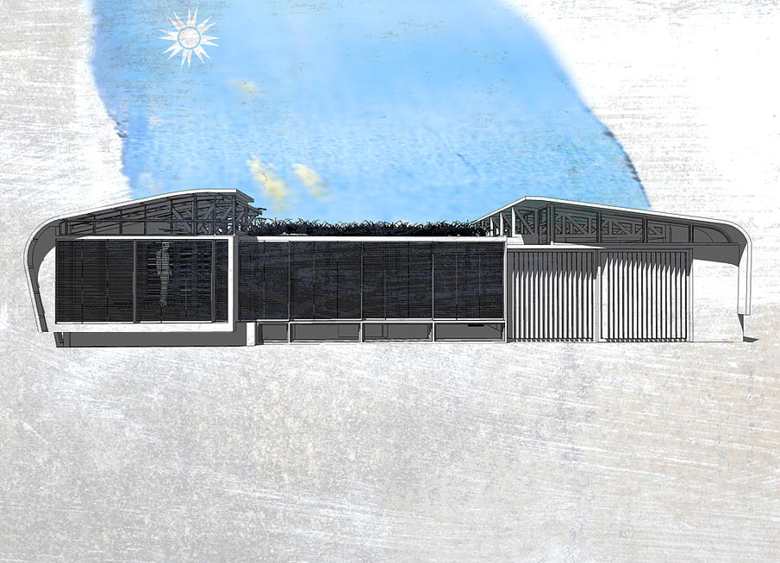

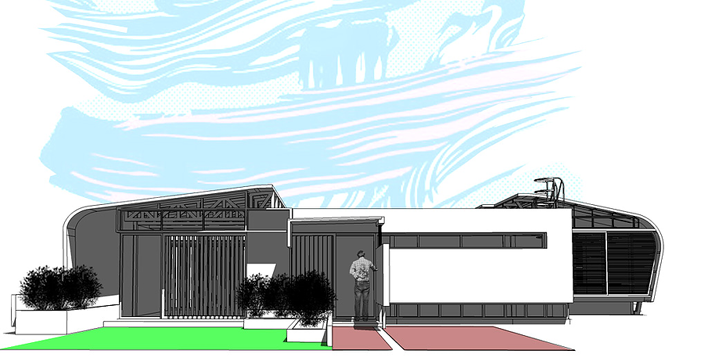

North-Central Florida is extremely hot and humid for several months of the year, and temperatures frequently drop below freezing in the winter. These conditions pose a problem for keeping interior temperatures comfortable without the use of energy intensive HVAC systems.

The traditional methods for dealing with the heat and humidity utilized natural ventilation. These methods are at odds with the sealed and insulated envelopes required for efficient HVAC use, posing a dilemma for architects and builders who wish to combine these two systems. The five design principles of the Spectacular Vernacular make it possible to utilize both of these methods simultaneously.

The 5 Points Toward a Spectacular Vernacular

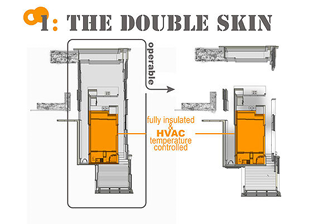

1: Double Skin

Exterior skin, fully operable and capable of opening to the exterior environment for ventilation.

Interior skin, insulated and sealed from the exterior environment, and conditioned with HVAC.

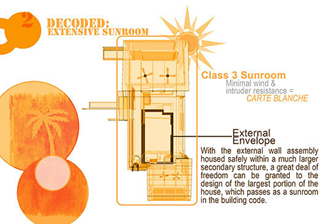

2: Sunroom: Code Benefits

The HVAC-serviced space defined by the interior skin is the only part of the house that counts as interior space under many local building codes if the “interior skin” is constructed as an exterior wall assembly. So the rest of the house, the lion’s share of the spaces defined by the fully operable secondary skin, are classified as a sunroom under the code, making the exterior operable skin an ancillary structure with fewer restrictions in design.

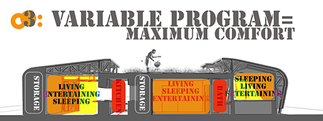

3: Variable Program:

The house’s three large spaces receive variable programming based on the whims of the occupants throughout the seasons. This lack of specificity was all but eradicated by the modernist tenet that form must follow function. Most functions are comfortable in a variety of forms. This is a lesson that can be learned just as easily from a Cracker House as from a Palladian Villa.

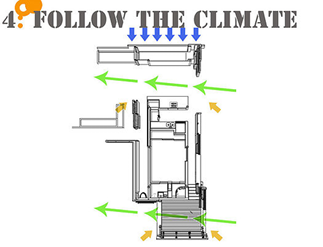

4: Follow the Climate:

North Central Florida is extremely hot and humid for several months of the year, and because of the humidity, sun shading is not enough to offer respite from the climate. During the hottest summer months, the wind is also little help; with average speeds clocking a mere five to six miles per hour, there just isn’t a lot of wind to replace the hot, sticky air in a semi-enclosed space. Added complications are the cold winter temperatures, which are frequently freezing at night during a few months of the year. A low-energy house will need to respond to both of these uncomfortable, possibly dangerous conditions.

The operable skin of the Spectacular Vernacular home is designed with the local, seasonal climatic conditions in mind. Block cold winds from the north in the winter, channel winds when appropriate in the summers, and allow complete access to air currents during spring and summer months, while providing ample shade.

5: Displacement Ventilation / “Hot Tin Roof”

When the wind fails to provide ample air-flow to relieve interior temperatures, the combination of a “hot tin roof” and a crawl-space can create relatively cool breezes in properly configured interiors. On the southern end of the house, a corrugated metal-wrapped wall and roof assembly is finished on the interior with insulated panels. The plenum space between the outer metal cladding and the interior insulated wall panels creates a hot-space baked by the Florida sun that can reach nearly 200° F. This hot-space is vented at the bottom and top, creating airflow as the air in the cavity heats and rises. Simultaneously, cool air from a shaded crawl-space below is sucked into the interior through porous wood plank flooring. Casement windows in the clerestory vent the hot air out of the interior overhead. Small fans in the clerestory can facilitate the process if necessary. The vent configuration can also be modified to heat the interior in cold winter months.

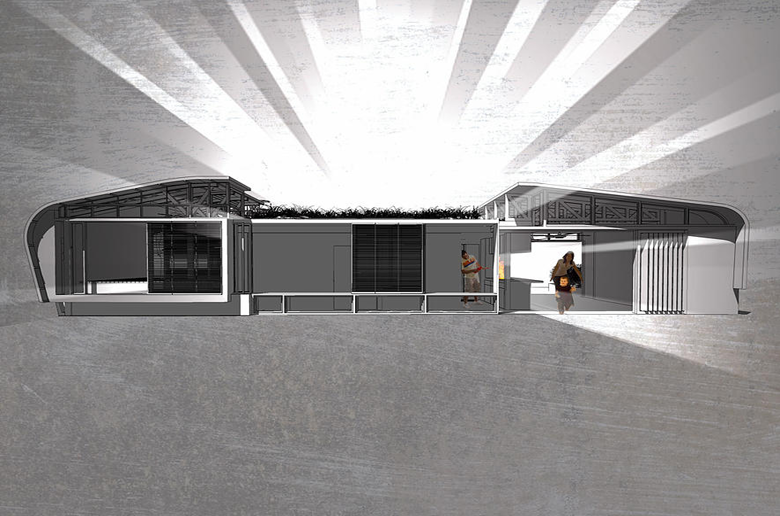

OUTPUT 1

DESIGN/BUILD PEDAGOGY OPPORTUNITY

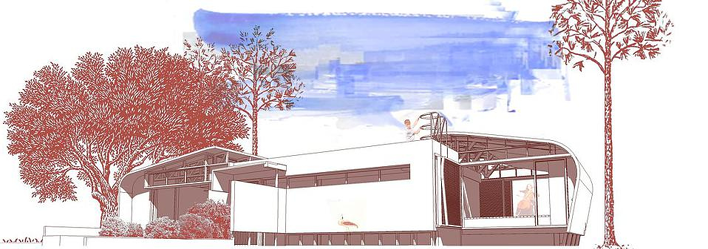

The proposal of a Spectacular Vernacular was not just to design a house that is both inexpensive and energy efficient for Florida’s climate: we wanted to propose a way of working—a method—that could produce such a building for any client on almost any site in North Central Florida.

Furthermore, the Spectacular Vernacular was intended to be utilized as the basis for an architectural design studio at the University of Florida in Gainesville, FL. As a pedagogical tool, the Spectacular Vernacular would become one component (the [T]heory) in each student’s design production, resulting in dozens, and eventually hundreds, of instances of the method’s application in production of individually tailored design methods, all of which could produce low-cost, low-energy housing in Florida.

OUTPUT 2

DOUGLASS NEIGHBORHOOD, HIGH SPRINGS

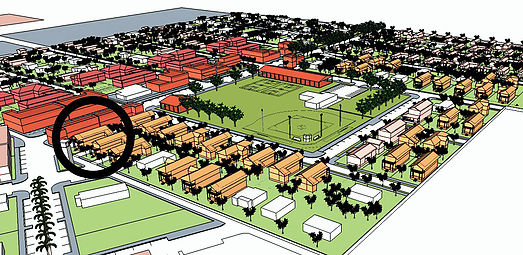

In the Spring of 2011, a design/build studio was planned as a collaboration between the City of High Springs, Florida and the School of Architecture at the University of Florida. Using the design principles of the Spectacular Vernacular, graduate and upper-division undergraduate students in architecture would design proposals for a low-cost single-family residence as a flagship component of the Douglass Neighborhood Planned Unit Development in High Springs.

Location of proposed site within the Douglass Neighborhood Development

OUTPUT 3

For the studio, students (individually or in small groups) would apply the Spectacular Vernacular as a [T]heory component in production of a new method for housing design using the CATTt Generator. The most effective design methods for the site in High Springs would be selected through multiple experimental iterations, eventually deciding on a single method to carry through design development and the production of construction documents for the residence over the first semester of the studio. Then, students would set to work building the residence over the course of the following spring semester and into summer semesters if necessary, with the end result being a family from the Douglass Neighborhood purchasing and moving into the house.

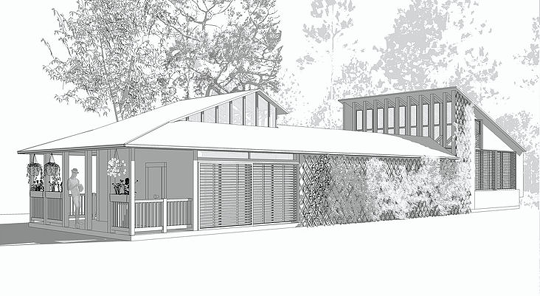

RESPONSE

SPECTACULAR VERNACULAR IN HIGH SPRINGS:

ANOTHER EXPERIMENT

It was necessary to use the CATTt Generator to produce a slightly different method experiment to respond to stakeholder reactions to the results of the initial method experiment. This time, the format needed to be tweaked to correspond to the specific [T]arget audience: the residents of High Springs and the Douglass Neighborhood in particular. Initial reactions from community members was that the proposed object looked like a spaceship or a mobile home more than a house. It was decided amongst the stakeholders that to be most appropriate for the Douglass Neighborhood, the results of the experimental method would need to be legible as a traditional Florida craftsman bungalow, a housing type historically popular in the Douglass Neighborhood and to which local residents still aspired. This change was easy to execute: the tail/tale, or format for the initial results of the proposed method, would need to be a Florida bungalow. The Spectacular Vernacular house for High Springs would also need to be slightly larger, as the future residents were likely to expect and need a two to three bedroom, two bath residence that featured room design that seemed more program specific, even if variable programing remained a key component in achieving comfort. In short, the [T]arget specificities led to a more detailed tail/tale format, and the Five Points were fleshed out with stipulations and requirements to adapt the method experiment to the Douglass Neighborhood development.

METHOD

Financial and political changes in High Springs led to the premature conclusion of the Douglass Neighborhood Development, and the Spectacular Vernacular design/build studio at UF was left without a site, client, or necessary funding. However, because the Spectacular Vernacular was not conceived of or presented as a finished object (the result of a completed design process), it is hard to kill: the proposed method for housing design in North Central Florida remains valid; the 5 Points Toward a Spectacular Vernacular are still applicable to future method experiments.