Pathos, or the ZAP!

INTRODUCTION || DISIDENTIFICATION || THEORY || TECHNOLOGY || QUEER RHETORIC || LOGOS || PATHOS || ETHOS || TONGUES || WORKS CITED

Visibility becomes, in so many significant ways, the pressing rhetorical strategy—and need—of LGBT rights movements. It is our demand for acknowledgement in the public sphere. But it also conditions numerous visual rhetorics and strategies, conjuring many other visual means of persuasion. Concomitant with the establishment of a queer rhetorical logic is a queering of pathos in the spectacle-laden realm of the public sphere.

Why does pathos need such visible queering? We all know the right kind of emotion-evoking queer—the kind that dies on fences in the Wyoming wilderness, that’s burned to death on a pile of old tires. These queers draw (deservingly so, we do not deny) public pity. So do the queers who weep on television because they can’t get married or because they’ve been kicked out of the military for an intimate misstep or unwanted declaration. Again, the public (mostly) pities these kinds of queers. These are the leftover residues of Wilde in Reading Gaol, of Whitman as Ginsberg has him in “A Supermarket in California,” a “lonely old grubber, poking among the meats in the refrigerator and eyeing the grocery boys” (29). That image elicits both pity and disgust—provocatively encapsulating in one visual gesture the dominant rhetorical depiction of queer pathos in the twentieth century.

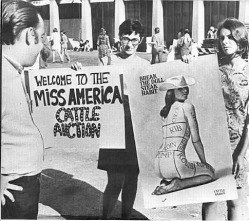

At crucial historical moments, some queers have rejected pity and disgust in favor of anger and outrage, evoking a long history of in-your-face activism. Indeed, queer activists from the 1970s on have drawn inspiration from the highly visual spectacles of some second-wave feminist and LGBT activism in the creation of queer zaps. A rich legacy of progressivist activism (and the kairotic moment; something was in the air) led to a mining of visually stunning rhetorical acts designed to unsettle, to provoke, to elicit strong emotional reactions in the service of jolting—zapping!—bias, prejudice, and ignorance of all kinds.

Robin Morgan, one of the founders of WITCH (Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell), noted that the group combined the “confrontational tactics of the male Left” with the “clownish proto-anarchism of such groups as the Yippies” (72) when engaging in zap actions. The use of “theatricality as a confrontational [and, we might add, rhetorical] act” (Dever 49) was a favored strategy of many late 1960s radical groups. WITCH’s most notorious action was the 1968 hexing of the New York Stock Exchange. Dressed as “Shamans, Faerie Queens, Matriarchal Old Sorceresses, and Guerilla Witches,” the group wound through a number of Wall Street venues following a “High Priestess bearing the papier-maché head of a pig on a golden platter garnished with greenery plucked from the poison money trees indigenous to the area” (Morgan 75). The group ended its zap by taking over a meeting about the media in order to discuss “theater, media, ideas, women, [and] the revolution” (Morgan 77).

According to GAA member Arthur Evans, zap actions worked not only to disrupt normative discourse, but also to educate gay people themselves:

-

Gays who have yet no sense of gay pride see a zap on television or read about it in the press. First they are vaguely disturbed at the demonstrators for “rocking the boat”; eventually, when they see how the straight establishment responds, they feel anger. This anger gradually focuses on the heterosexual oppressors, and the gays develop a sense of class-consciousness. And the no-longer-closeted gays realize that assimilation into the heterosexual mainstream is no answer: gays must unite among themselves, organize their common resources for collective action, and resist. (qtd. in Gross 46)

September, 1968: New York Radical Feminists' (NYRF) protest against Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City, NJ. Online image.

Similarly, as Carolyn Dever writes, feminist zap actions used this self-conscious theater “as a means of education; like consciousness-raising groups, they worked evocatively, dramatizing the circumstances” of oppression in order to bring those circumstances into the light—in this case, the light of media. These actions combined street theatre and humor with a knowledge of media so that after the zap was done, protestors created the queer subject themselves. That is, the “zap and hype” two-step of 1960s protestors created a mediated space for subject formation, a way to claim the power of definition of the group. We are here, and this is what we look like/do/demand.