Sharon Yam, University of Kentucky

(Published October 9, 2017)

As a British colony from 1841 to 1997 and now a semi-independent “special administrative region” under China’s sovereignty, Hong Kong is a city saturated with cultural hybridity and seeming ideological and political contradictions that are apparent in everyday life—particularly in the cultivation of social desires and tastes. During the British colonial era, many middle-class, local Hongkongers were fascinated by the Western cuisines consumed by the ruling elites in the city. Because such food was available only in expensive upscale restaurants, in the 1960s and ‘70s local entrepreneurs began establishing bing sutt (冰室; ice houses) that sold inventive hybrid drinks and snacks. Although these snacks incorporated common Western ingredients such as butter, ice cream, and pasta, they were creatively adapted to fit a middle-class budget and appeal to local taste buds (Au). Bing sutt quickly acquired additional social and cultural significance as they became popular community spaces where families and nearby workers gathered to socialize (Chow). The “original” bing sutt, in other words, was a cultural hybrid made possible through transnational exchanges, tastes, and consumptions. Bing sutts, however, began to lose its popularity in the 1980s and ‘90s when Hong Kong became a prominent player in the global capitalist market. Quickly, family-run bing sutts were replaced by cha chaan tengs (茶餐廳; tea restaurants)—larger, fast-food-style eateries that sell not only snacks but also cheap Canto-Western entrees throughout the night to accommodate Hongkongers’ long work hours. Soon, international and local fast-food franchises joined and dominated the local market. Because of these developments, there are now approximately only fifty bing sutts left in the city, struggling to stay open. Despite this shift in Hong Kong’s economic, spatial, and cultural milieu, bing sutts continue to be seen by both the local and transnational public as historical and cultural icons of the city.

It was, therefore, a pleasant surprise and a spectacle for Hongkongers when Starbucks recreated and opened its version of a bing sutt in the city in 2009. The Starbucks on Duddell Street is, as the company boasts, “the world’s first-ever Starbucks store to incorporate a bing sutt corner—fusing together a nostalgic retro style with a contemporary coffeehouse design” (“Duddell Street”). This store is divided spatially into two sections: although patrons are first greeted with the usual plush armchairs and round wooden coffee tables, when they turn a corner, they find themselves entering a simulacrum of a bing sutt. Designed and created in collaboration with a popular local lifestyle company, Starbucks’s Bing Sutt soon became a favorite attraction for young Hongkongers and tourists from nearby Asian countries like Singapore, Malaysia, and Taiwan. Even though Starbucks’s Bing Sutt purports to be “a celebration of Hong Kong roots and spirits” through the recreation of a disappearing communal space (“Duddell Street”), it functions more as a transnational site of consumption where a particular kind of local cultural memory is commodified as a carnivalesque, apolitical, and Instagrammable spectacle for both local and transnational visitors to consume.

By adopting a transnational rhetorical approach and drawing from studies on memory, branding, and space, I address the following questions: How does a transnational corporation (TNC) like Starbucks selectively remediate locale-specific cultural memory? How do corporations and consumers reconstruct and repurpose local cultural memories to accomplish their respective economic and cultural agendas in a transnational context? Previous research in spatial and material rhetorics has interrogated how Starbucks—as a transnational, globalizing institution and force—acts on particular locales and impacts local consumer subjects ( Aiello and Dickinson; Dickinson; Mathieu). In this article, I expand the scope of such research to examine the ways in which consumers outside of dominant, EuroAmerican countries make use of TNCs like Starbucks to construct a desirable, cosmopolitan subjectivity for themselves. As such, this article not only examines the rhetorical consequence and mode of Starbucks’s Bing Sutt but also pays attention to the ways “people (re)write and (re)read themselves into local and global contexts against and beyond the social relations, institutions, spaces, and economic processes of global capitalism and neoliberal governmentality” (Dingo et al. 523).

Such transnational consumption of commodified social memory does not necessarily prompt any political critiques or particular affiliations and solidarities. Instead, the space encourages and enables visitors to inhabit a cosmopolitan consumer subjectivity. As nostalgic memory kitsch, Starbucks’s Bing Sutt effectively underplays the complex economic and political causes of local cultural loss by prompting visitors to act merely as spectators and consumers who derive pleasure from the dismissal of specific sociocultural and economic contexts. By consuming products from a prominent transnational brand while inhabiting what appears to be a cultural memory place, visitors of Starbucks’s Bing Sutt occupy the valued subjectivity of transnational, “multicultural” cosmopolitans—a subject position that has only recently become available to middle-class Asians.

Drawing from my own on-site observations and social media content generated by customers, I conduct a spatial and rhetorical analysis of Starbucks’s Bing Sutt in Hong Kong. I interrogate how Starbucks commodifies bing sutt as a Hong Kong cultural icon to construct a nostalgic memory kitsch that functions as a tourist site; in particular, I examine the ways Starbucks selects an uncontroversial and seemingly apolitical segment of local cultural memory and commodifies it into easily consumable, transnational touristic spectacle. This rhetorical and spatial technique prompts visitors to adopt a playful and blithe attitude towards Hong Kong’s history and shifting cultural and economic landscape while feeling like they are developing personal connections with what they perceive to be the city’s collective memory. I also examine the kinds of responses the site elicits from local and transnational customers from Asia—their reactions demonstrate that Starbucks’s Bing Sutt allows them to perform as privileged, cosmopolitan subjects who embrace both traditional, local “cultural authenticity” and modern EuroAmerican culture. Attuned to the way sociocultural hybridity and adaptations materialize through everyday spaces and practices, this article “describes juxtapositions, pastiche, and functional inconsistency” (Bruner 94) to illuminate the performances, identities, and subject positions that are made possible by transnational consumerism and globalization.

Many have argued that authenticity is a symbolic construct and rhetorical effect produced by particular performances (Aiello and Dickinson; Banet-Weiser; Bruner); as such, I do not evaluate Starbucks’s Bing Sutt with any supposed sense of authenticity nor do I treat authenticity as an objective quality. Rather, echoing Sarah Banet-Weiser, I see the corporate remediation of local cultural memory as a process of affective, cultural, and economic exchange between consumers and capitalist business practices. When I evoke authenticity, I am referring to the desire among consumers to believe that certain spaces and artifacts lie outside of capitalist exchange and are imbued with genuine and identifiable cultural and emotional intimacy.

Memory Kitsch, Scotosis, and Cosmopolitan Consumer Subjectivity

To engage further with what Kendall Philips and G. Mitchell Reyes coin the “global memoryscape” (13)—how memories and the representations and performances of memories travel and interact across state and local borders—rhetoricians must pay attention to the way transnational, non-state actors mediate, repurpose, disseminate, and circulate cultural memories that have been rendered portable and malleable to fulfill specific economic and sociopolitical agendas. By adopting a transnational lens to study the commodification, circulation, and consumption of cultural memory, we will better understand the linkages across different actors and how transnational flows of capital and power influence the way local cultural memories are mediated, repurposed, and deployed.

The concept of prosthetic memories aptly captures the conditions in which memory artifacts circulate and are consumed across transnational economic and cultural networks. Distinguishing prosthetic memories from more conventional understandings of social and cultural memories, Alison Landsberg defines the former as “privately felt public memories that develop after an encounter with a mass cultural representation of the past” made largely possible through commodity culture and capitalism (19). Because of their commodified form, prosthetic memories are interchangeable and exchangeable. Unlike conventional cultural memory that “narrates shared identities…shared and embraced as a marker of identity for that group” (Dickinson et al. 13), prosthetic memory does not necessarily construct or maintain social cohesion via established logics of group identity. Rather, as Landsberg argues, the mass-mediated, non-essentialist, malleable, and transportable nature of prosthetic memories rejects a single dominant collective identity, narrative, and way of remembrance. Although prosthetic memories defy monopolizing claims of ownership, they remain susceptible to co-optation by dominant transnational actors who promulgate a particular kind of experience and narrative through the remediation and dissemination processes.

These features, therefore, prompt ethical questions about the implications of prosthetic memories—particularly when the cultural memories of marginalized groups are commodified as kitsch for transnational consumptions. While Landsberg argues that prosthetic memories carry tremendous political and ethical potential because they foster empathy across and without the erasure of difference, the ways such memories are mediated and disseminated often encourage consumers to respond with prepackaged and uncritical emotions. These responses are promoted and prompted more often when the prosthetic memory is mediated through kitschy touristic spectacles. Using Ground Zero and the Oklahoma City Memorial as examples, Marita Sturken argues that when collective cultural memory is represented and consumed as touristic kitsch, visitors remain in their emotional and political comfort zone without reflecting critically on the historical, economic, and social causes of those events and spaces. The appeal behind a kitschy memory object or site is that by connecting cultural memory with consumerism and tourism, it allows visitors to feel that they have sufficiently engaged with a particular historical event without ever feeling negative (but politically productive) emotions such as anger, defiance, and shame.

Powerful TNCs like Starbucks are well-positioned to deploy memory kitsch at specific locales to bolster their own ethos. Amidst rampant criticism of globalization and neoliberalism, corporations often engage in branding projects that demonstrate their commitment to social responsibility (DeChaine). Paying homage to local collective memory at non-Western locales allows TNCs to eschew blame, market a sense of authenticity, and garner loyalty among consumers (Banet-Weiser). The success of these branding projects hinges in part on how effective the TNCs are in inducing “scotosis” among their consumers: or as Paula Mathieu puts it, “rationalized acts of selective blindness that occur by allowing certain information to be discounted or unexamined” (114-115). Echoing Sturken’s argument on memory kitsch, Mathieu makes clear through her analysis of Starbucks as a transnational brand that under the effect of scotosis, “one isn’t duped, nor are false needs created. Rather, one is persuaded by the justifications offered within the narratives to remain, perhaps only momentarily or uncomfortably, within its parameters. It is thinking and acting within the frame offered” (115). Scotosis not only benefits the brand by enhancing consumer loyalty but also allows consumers to feel good about themselves—very much like the consumption of touristic memory kitsch. Both offer consumers comfort by encouraging them to remain within a familiar template of emotional and political response towards an otherwise complex and uncomfortable event or context.

For consumers outside of the dominant Western context, the brand narratives and embodied experiences TNCs offer have added significance beyond the comfort and reassurance of familiarity; by participating in transnational brand cultures orchestrated largely by EuroAmerican companies, they enact the subjectivity of cosmopolitan consumer-agents. This subjectivity is valued because EuroAmerican corporations have only recently recognized the purchasing power of people in Asia and started accounting for their economic decisions and preferences (Grewal). In a non-Western postcolonial context, such recognition carries important cultural significance. As Banet-Weiser argues, because cultural and economic transactions are interwoven within brand culture, consumers are often purchasing immaterial things such as particular subject positions or identities. In a postcolonial space like Hong Kong, concepts of modernity and cosmopolitanism often remain tethered to dominant Western white culture (Chatterjee; Vickers). To participate in brand culture and be recognized by TNCs, therefore, is to have one’s subjectivity validated in the dominant transnational economic and cultural network.

Cosmopolitanism has, as Aihwa Ong and Caren Kaplan point out, historically been associated with representations of white EuroAmericans as progressive, intellectual “world citizens” who have the nomadic power to travel at will and temporarily become “natives” while retaining their white privilege and identity. Under the current neoliberal regime, cosmopolitan subjectivity is tied not only to white privilege but also to transnational consumption—to be cosmopolitan is to be a “global consumer, marked by his or her recognition of global brand names” (Grewal 94). However, the cosmopolitan consumer culture is not deployed or experienced universally across contexts. Rather, Inderpal Grewal argues that TNCs adapt and repurpose local cultural symbols to deploy them simultaneously with their dominant, and, often Western, brand markers. By deploying repurposed local cultural symbols, TNC project the aura of locality and authenticity while simultaneously appealing to consumers who subscribe to the ideology of Western superiority and modernity. Such rhetorical strategies allow consumers in non-Western contexts to temporarily assume the subject positions of EuroAmerican consumers, while at the same time performing “boutique multiculturalism,” which is to “admire or appreciate or enjoy or sympathize with or (at the very least) ‘recognize the legitimacy’ of the traditions of cultures other than their own” (Fish 378).

Background and Context

Starbucks’s Bing Sutt was designed and created in collaboration with G.O.D.—a local lifestyle and design company opened in 2001 that is famous for its irreverent remediations of nostalgic cultural symbols and its pioneering role in commodifying memory kitsch. G.O.D.—a homophonic translation of the Cantonese phrase “living better,”—is an increasingly popular brand among young, hip, middle-class Hongkongers who identify as cultured tastemakers. Following wild success in recent years, the company has expanded to Taiwan, Singapore, and mainland China—appealing to a similar demographic in those locations. It is, therefore, not a surprise that consumers who frequent Starbucks’s Bing Sutt—those who Instagram and blog about the space—are also primarily of that particular demographic. Selling goods such as boxer briefs patterned with ’60s’ Hong Kong mailboxes and traditionally packaged mooncakes amusingly shaped like butt cheeks, G.O.D. transforms cultural symbols and icons that were once old-fashioned into nostalgic, kitschy, and playful products.

In recent years, many local, independent designers have followed suit. During a quick trip to PMQ—a historic police quarter remodeled into a mall—one could easily find a variety of trinkets and designs that pay homage to collective cultural memory in Hong Kong:reprints of government posters from the colonial era, updated designs of the iconic red-white-blue canvas bags, dioramas created out of pictures of buildings and street signs from the ’60s and ’70s, and toys that model signature public housing structures that have since been abolished.1

The revival of collective cultural memory as commercial, kitsch objects coincides with two intersecting cultural and political forces: 1) rampant real estate development and gentrification, and 2) increased ideological encroachment and control by the mainland Chinese government, which has significantly altered the social milieu of Hong Kong. Because the Chinese and Hong Kong governments both privilege capitalist economic development over historic preservation, the city has in the past decade dismantled many landmark architectures built and used during the colonial era (Au-yeung; Spencer). On the other hand, mainland China’s aggressive political and legal infringement has led to a surge in nationalist sentiments and narratives among local Hongkongers who think their cultural and political identity is under siege and thus are desperate to construct and concretize an identity that is “uniquely” Hong Kong (Yam “Affective”).2 As a result, many Hongkongers express outrage and grief over the demolition of architectures that they never experienced firsthand as a demonstration of their anxiety.

In this context of perceived cultural loss and political frustration, nostalgic kitsch fills a significant emotional, cultural, and political role. As Celeste Olaquiaga points out, “kitsch is the attempt to repossess the experience of intensity and immediacy through an object” (291). Nostalgic kitsch, she argues, functions as a soothing remembrance that underplays the sense of loss and grief. In other words, the consumption of these nostalgic kitsch objects provides Hongkongers reprieve from their perceived identity loss while simultaneously serving as memory prosthetics that allow them to engage with a collective past that they have never themselves experienced. Although Starbucks’s Bing Sutt appears to serve rhetorical functions similar to the nostalgic kitsch objects designed and sold by local Hong Kong artists, the fact that the commodification and marketing of cultural memory is done by a TNC significantly alters the cultural and political implications of the act.

A Rhetorical Analysis of Starbucks’s Bing Sutt

Situated on Duddell Street—a street in the central financial district of Hong Kong famous for its long, romantic, stone staircase and gas lamps—Starbucks’s Bing Sutt attracted significant local attention when it first opened in 2009. Marketed by the company as “a blend of Western modernization and Eastern traditions that celebrates the timeless heritage of coffee in Hong Kong, both past and present” (”Duddell Street”), Starbucks’s Bing Sutt exemplifies the corporation’s attempt to enact and romanticize “glocalized” hybridity. Given that Starbucks and the neoliberal forces it benefits from have contributed directly to the disappearance of the city’s bing sutts, this Starbucks store enacts the tension of simultaneously displacing and replacing local cultural artifacts and memory sites. The move to glocalize, as Grewal points out through her analysis of Mattel’s marketing of white Barbies in saris to the Indian market, is economically beneficial for the corporation because “a very mediated notion of America” allows the brand to demonstrate its ability to “be local,” which boosts sales and ethos more effectively than “Americanization and simple cultural imperialism” (94). At the same time, the brand retains its American identity as cultural capital to bring in consumers from non-Western, particularly postcolonial, locales. Starbucks’s Bing Sutt is one such example; as a glocalizing rhetorical project that mobilizes local cultural memory as kitsch, it attracts not only local Hong Kong consumers but also tourists visiting the city from other Asian countries. To accomplish such transglocal appeal, the space must exude a sufficient amount of “cultural authenticity” while still maintaining the overarching brand ethos and narrative to induce scotosis—particularly among consumers who are already familiar with the brand.

Starbucks’s glocalizing strategy is demonstrated and felt most explicitly through the Bing Sutt’s location and its spatial arrangement. As Giorgia Aiello and Greg Dickinson point out after analyzing four redesigned Starbucks stores in Seattle, the corporation designs stores in ways that “both visualize and materialize the ethos of locality by deploying major meaning potentials of materiality and community, while also highlighting meaning potentials such as hereness, heritage, and local practices of elsewhere” (308). Located on a street commonly used as a romantic film set by local film directors, Starbucks’s Bing Sutt constructs the aura of locality with its culturally and historically specific emplacement within Hong Kong’s urban landscape. The store itself is divided into two distinct sections. When one first enters, the store appears to be no different than any other Starbucks coffee shop: a large burgundy wall with nondescript, beige decorative quotes surrounded by brown velvet chairs, couches, and wooden tables. The few black-and-white photographs of an actual bing sutt and of the Duddell Street staircase in the ’60s hang next to bright, cheerful corporate posters that celebrate the different origins of the company’s coffee beans. Although the barista stand appears conventional at first glance, one will notice baked goods in the display window that are not usually sold at other Starbucks locations: egg tarts, paper cakes,3 and “rustic buns with thick-cut butter”—a popular local pastry commonly referred to as a Pineapple Bun because of its checkered appearance. The offering of local baked goods supports the store’s attempt to create the ethos of locality and authenticity by signaling what Aiello and Dickinson refer to as a sense of “hereness” (314)which highlights the store’s intimate, local emplacement. . Other than the three local baked goods, the coffee menu and the ordering process resembles any other Starbucks locations. During my observations in the coffee shop, the “Western and modern” part of the store was commonly occupied by businesspeople in the financial district, mainland Chinese tourists, and domestic workers who stopped in for a quick cup of coffee or to rest their feet. Most customers in this section left the store promptly and did not pay much attention to the specialty baked goods on display. This first section, in other words, is almost identical to a typical Starbucks: a “non-place” that provides transient consumers with the familiarity of the brand’s consistent decorations, practice, and service. Visitors have few reasons to dwell in the space once they accomplish their primary goals.

The other section of the coffee shop, however, is drastically different both in both spatial layout and atmosphere. The bar area serves as a divider between the two sections: entering the other side of the coffee shop is almost akin to entering an entirely different space and time (Fig. 1 and 2). Rather than non-descript stuffed chairs and couches, this side is furnished with the kinds of glass-top tables and hard wooden chairs and benches one would find in a local diner. On the walls are bright red placards with the names of signature Starbucks drinks written in white, Chinese characters. These decorative features construct an air of authenticity because they “administer the right amount of specific semiotic features” to achieve what is considered to be emblematic of a particular cultural space and identity (Blommaert and Varis 150). Although the décor and furniture here resemble those of a traditional bing sutt, the sight through the dark green, metal window frames suggests otherwise: instead of actual streets and buildings outside of the coffee shop, one sees a cacophonic juxtaposition of gigantic, exaggerated neon signs, colorful Cantonese theater banners and flags, large black-and-white scripts mimicking the style of a famed local graffiti artist, and photographic prints of city buildings in the ’80s. The dramatic flair and the playful style of the design echo those of an amusement park—a site that encourages pleasure, consumption, the suspension of judgment and critique, and photo-taking. Visitors are intrigued and attracted to the seeming incongruence between the Starbucks brand and the design of a bing sutt; at the same time, the flamboyant and semi-realistic interior decorations render the space aesthetically pleasing.. The particular textures and materials found in the Bing Sutt Corner further evoke the ethos of locality in a way that connects with the production of prosthetic memory. As Aiello and Dickinson point out, “texture summons us to identify with the experiential rather than merely symbolic implications of manifestations” (309). The experience of materiality—specifically, materiality that highlights Hong Kong’s heritage—prompts consumers to feel that they are securely anchored in a site that honors the city’s unique cultural memory.

Fig. 1. View of the Bing Sutt Corner from the bar.

Fig. 2. Window decorations that feature G.O.D.’s signature style: exaggerated, playful, and nostalgic. (IMAG 2284)

As the in-store and online descriptions of Starbucks’s Bing Sutt make clear, the decoration and design of the space is done primarily by G.O.D. By collaborating with this brand, Starbucks transforms one part of the storefront into a carnivalesque, nostalgic memory kitsch that attracts consumers who wish to consume Starbucks products ( along with its white, American brand ethos) while simultaneously embracing “authentic” Hong Kong culture. As the corporation boasts on its website, “with decorations and traits to blend the Hong Kong style from the ‘50s through the ‘70s with today’s sensibilities. Stepping into the Duddell Street Starbucks will be like stepping back in time” (”Duddell Street”). This description emphasizes the kitschy, playful, and touristic nature of the Bing Sutt Corner while dehistoricizing and depoliticizing the specific context and memories associated with local bing sutts and their gradual disappearance under the forces of gentrification and globalization. By promoting the Bing Sutt Corner as a memory place one can easily step in and out of, Starbucks folds a specific local cultural memory into its dominant brand narrative of consumption, pleasure, and authenticity. Consumers who visit Starbucks’s Bing Sutt are encouraged to think of the space not as a symbol of cultural history but as a touristic site for amusement they can temporarily inhabit and thus feel that they have been “authentically” close to Hong Kong’s local culture without ever leaving the comfortable brand narrative of Starbucks. The exaggerated and glib décor in the store, for instance, is so colorful and unique (as the corporation always emphasizes, there is “only one” Starbucks Bing Sutt in the world) that it encourages touristic photo-taking instead of questioning. As Sturken rightly points out, memory kitsch is popular not only because the site puts consumers in a state of scotosis but also because consumers often prefer an unthreatening and entertaining encounter with history that allows them to respond using a given emotional template. One does not expect to interrogate complex historical and sociocultural issues when entering a Starbucks—let alone one that is decorated as a site of carnivalesque celebration.

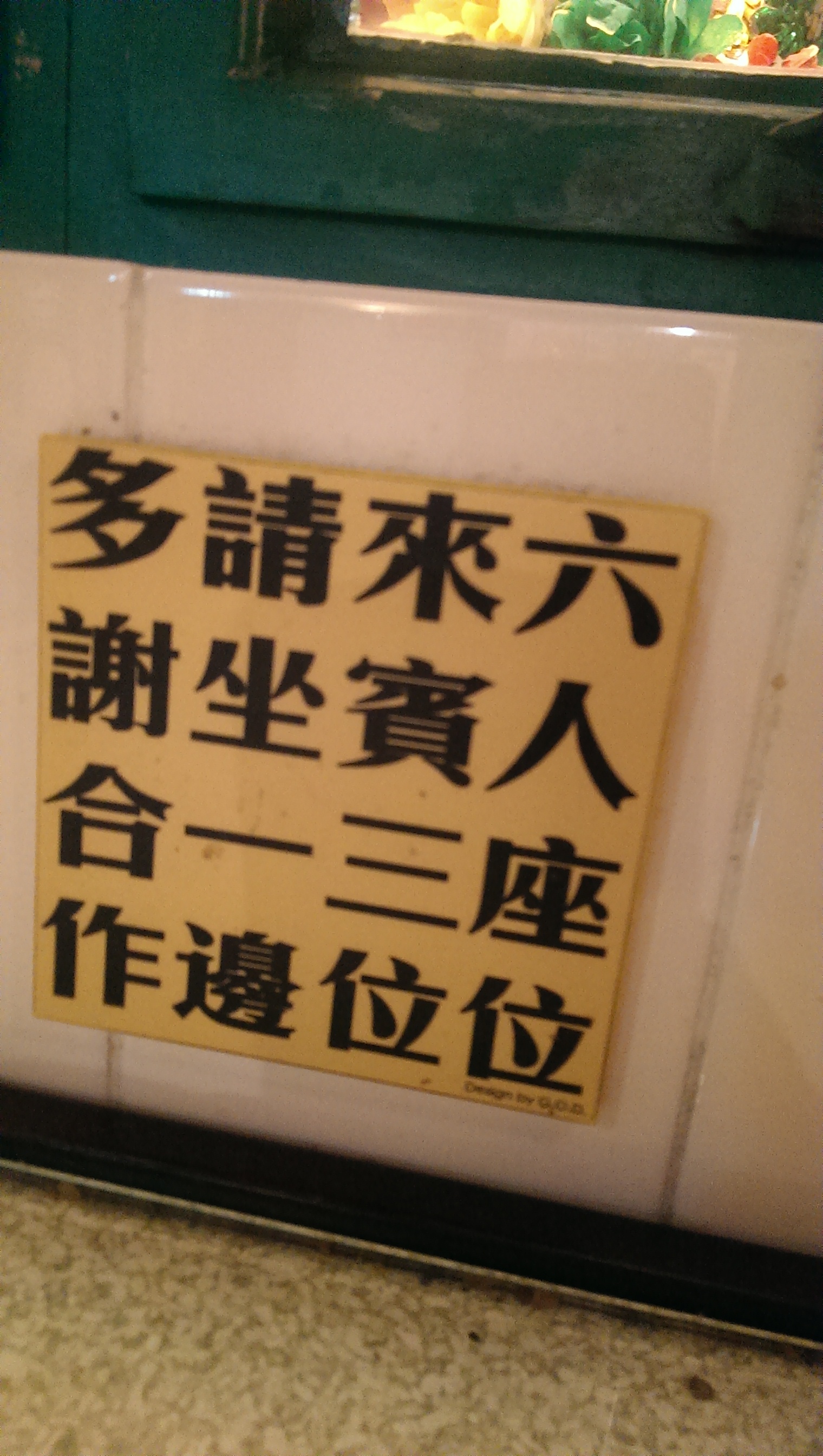

In addition to the overall design and layout of the space, the minute details scattered throughout the Bing Sutt Corner project an air of supposed cultural authenticity that allows visitors to feel as if they are developing genuine ties to the cultural memories of Hong Kong—a feeling at once reassuring and exciting. For example, on the side of each booth is a small, square Chinese notice in a retro font, printed vertically in four lines that reads from right to left: “Six-people seats; three guests; please sit on one side; thank you for your cooperation” (Fig. 4, my trans.). Although written in Chinese, the grammar and style of the text resemble spoken Cantonese—the native language used by most Hongkongers, which differs semantically and phonetically from the dominant, Mandarin Chinese used by most Asian tourists. In other words, tourists from other countries such as Taiwan, Singapore, and Mainland China may understand the sign but nevertheless find the grammar confusing and strange. Although Aiello and Dickinson suggest that certain linguistic and typographic cues of authenticity “are sometimes only noticeable to those who are ‘in the know’” (316), this example demonstrates that such cues can also act on those who cannot fully decipher them. Although Hongkongers will recognize the sign as a reference to the language and practice of communal seating from traditional eateries, tourists may liken such strangeness to their proximity to “real, historical,” local Hong Kong culture. By developing and possessing such prosthetic memories through the simple, undemanding act of sitting in the booth and consuming the sign, Hongkongers and tourists alike are able to cultivate their consumer, cosmopolitan identity.

Fig. 3. Wall decorations in the Bing Sutt Corner.

Fig. 4. Notice posted in each booth.

The realistic yet carnivalesque decorations of the Starbucks Bing Sutt transform this space from a common, transnational non-place to a memory place in masquerade—a site seemingly for the remembrance of cultural memory and for the construction and transnational dissemination of prosthetic memories. But given the touristic, kitschy, and corporate nature of the site, contradictions and tensions are always present, thereby troubling our current understanding of cultural memory, remembrance, and place. The intimate connection between place and memory is well-rehearsed. As Edward Casey cogently points out, for public remembrance of cultural memory to occur, there must be a place that “lends itself to the remembering and facilitates it at the very least, but also in certain cases embodies the memory itself” (32); practically speaking, the memory place also “offers a space in which human bodies can come into proximity…for the sake of a public presence that can be accomplished only when people congregate for a common purpose” (33). The proximity and co-presence, in turn, stimulates public, direct communications over a shared topic or concern related to the collective memory.

On the surface, Starbucks’s Bing Sutt has the potential to serve several different audiences as a memory place; such potential, however, is unsurprisingly overshadowed and subsumed by the brand’s neoliberal corporate project and the cosmopolitan consumer subjectivity coveted by most visitors. A survey of travel blogs and Instagram photos suggests that most patrons who choose to dwell in the Bing Sutt Corner are younger local Hongkongers who have never intimately inhabited an independent bing sutt before but nevertheless would like to embody such collective cultural memory through a simulacrum; Bing Sutt Corner is also popular amongst tourists from nearby Asian countries who are cultivating prosthetic memories of the city as a form of entertainment. They are, in other words, what Sturken refers to as “tourists of history,” or those “for whom history is an experience once or twice removed, a mediated and reenacted experience, yet an experience nevertheless” (9). Instead of reflecting on the social significance and history of local bing sutts, consumers are invited to enjoy their global brand-name coffee and snacks while marveling in the nostalgic and carnivalesque décor that gives an aura of cosmopolitanism infused with local cultural sensitivities and authenticity.

On-Site Observations and Self-Reflection

To fully experience the space and to observe how it is used and inhabited by visitors, I spent numerous hours from June to August, 2015 dwelling in the Bing Sutt Corner. My particular positionality and identity influenced the ways I occupied, experienced, and interpreted this space and the cultural, political, and economic implications it carries. As a native Hongkonger who grew up at the cusp of the transition of sovereignty from Britain to China, I am intimately familiar with the neocolonial desire for Western modernity that often arises in tandem with the fear of political and cultural incorporation from mainland China. The privileging of Western modernity, in particular, is especially prevalent in recent years as mainstream Hongkongers draw from the city’s colonial history and Western superiority to distinguish themselves from their mainland Chinese counterparts (Yam “Education”). Thus, the nostalgic revival of what is perceived to be uniquely Hong Kong and the increased popularity of Western brands and practices(such as sipping an expensive caffeinated drink at a chain coffee shop) was no surprise to me when I visited. Much to my chagrin, in fact, I frequently welcomed the sight of the green mermaid logo. Those two months in 2015 constituted my first visit to the city in five years after moving to the U.S. ten years ago; and despite my eagerness to act and be perceived as an “authentic” Hongkonger, at times I found myself craving the predictable and familiar comfort of Starbucks after wandering along the city’s crowded and sometimes disorienting streets in its subtropical, humid, sweltering heat. Inevitably, such conflicting desires and my hybrid cultural identity have complicated my analysis and experience of the Starbucks Bing Sutt.

During my observations, the Bing Sutt Corner was often populated by visitors who spent a substantial amount of time in the space—it was not uncommon to find groups of young people having social gatherings and taking pictures of their drinks and the store with their cellphones. Indeed, the atmosphere and décor invites visitors to dwell in the space as a touristic spectacle of non-descript cultural meaning that seems somehow locale-specific and authentic. If I were to sit inside a booth that faced the back of the coffee shop, I would not be able to see the entrance and the conventional, modern section of the store at all: instead, I would be gazing at the handwritten Chinese menus on the central pillar, colorful ’70s posters on the side walls, and covered bird cages and large wooden fans hung close to the ceiling. At the same time, however, I would still be reminded that I am inside a Starbucks by the iconic mermaid logo on the wall and on my own coffee cup. Despite the constructed air of local cultural authenticity in the Bing Sutt Corner, consumers are nevertheless always reminded of their subject position as consumers of a global brand.

As someone who is too young to have personally experienced Hong Kong’s bing sutt culture, I occupy a subject position that is similar to the position of most patrons at the Starbucks Bing Sutt, in which there is no intimate sense of loss or the experience of any personal, embodied memories. Starbucks’s Bing Sutt, in other words, is more potent as a space that inculcates prosthetic memories than it is as a memory place. As I sat in the booth, I was acutely aware of the consumerist appropriation that takes place at the Starbucks Bing Sutt; I nevertheless found it difficult to construct any cogent critique beyond that.It is not a surprise, after all, that Starbucks deploys glocalizing strategies to appeal to a specific market.Such strategies produce an almost universal consumer experience that encourages brand loyalty and discourages interrogation and alternative perspectives of the context and the space. At the same time, it is unlikely that the primary audience here would critically consider the cultural significance of local bing sutts under any conditions because bing sutts were removed from their lived experiences before the construction of this Starbucks. Thus, as I surveyed and took my first seat at the Bing Sutt Corner, I was hard pressed to form much significant and original rhetorical criticism.

The novelty of the space also makes it incredibly easy to focus solely on the consumption. While I inhabited the space, I was quickly overtaken with curiosity and excitement by the kitschiness that so deftly and playfully incorporates recognizable symbols and designs of cultural nostalgia. Despite knowing that the posters, signs, and menus on the wall are mere imitations, I was giddy to be physically surrounded by artifacts that I had previously only seen in photographs and heard described in historical narratives and family stories; thus, I temporarily removed my questioning gaze and instead participated as a tourist-consumer who thoroughly enjoyed the entertainment. Indeed, as anthropologist Edward Bruner points out, “tourists…have the ability to simultaneously suspend disbelief and harbor inner doubts, and sometimes to oscillate between one stance and the other” (97). The pastiche and nostalgic kitsch that populates Starbucks’s Bing Sutt encourages exactly this kind of participation and consumption from its consumers.

During my second visit to the site, however, it struck me that instead of sitting at a kitschy Starbucks brimmed with curiosity, I could visit an actual local bing sutt. I could not help but wonder: if I was serious about experiencing a local memory place to interrogate its sociocultural effects and implications, why had I not patronized one of the fifty remaining bing sutts in the city—especially when one was located right next to my summer home? Although I would discreetly peek into that bing sutt every time I walked by, I always felt too intimidated to enter and be an actual patron there. Having resided in the U.S. since my late teens and never having learnt the norms and expected behaviors in a local bing sutt, I was sure that my “foreignness” would be painfully obvious in my uneasy postures and sometimes awkwardly slow and choppy Cantonese speech. Worst of all, the bing sutt was extremely small and would render all interactions acutely visible to the other customers in the space—regular patrons who have established an intimate relationship with each other, the staff, and the space. My otherness as an “inauthentic” Hongkonger, in other words, would be magnified and highlighted. At the same time, I yearned to experience the memory place in a physical and material way because to dwell in a bing sutt is to come into intimate contact with the collective cultural history of Hong Kong.

If entering a local bing sutt felt risky and potentially alienating to me, visiting Starbucks’s Bing Sutt, on the contrary, felt safe and familiar because it was filled with customers who shared a similar subject position as I did: young, transnationally mobile, and devoid of any personal experiences with the origin of the particular cultural memory. If the local bing sutt down the street made me feel a slight tinge of shame about my “inauthenticity” as a Hongkonger after ten years abroad, Starbucks’s Bing Sutt reinforced the identity I was attempting to hold onto—that I am nevertheless still a Hongkonger, connected to the city and the community in an intimate way.4 At Starbucks’s Bing Sutt, I could hide from the rustiness of my local cultural knowledge, critique the corporation for appropriating and commodifying collective memory, and secretly revel in the playground-like atmosphere and design of the space. Embarrassingly, the contrasting reactions I had towards Starbucks and the local bing sutt made me feel secretly proud that I had “made it”: that I have become so successfully Americanized that I identify as more white than Chinese.

The site, in fact, serves multiple functions for consumers like me. First, it is easier and much more comfortable for someone of my subject position to perform the role of a cosmopolitan consumer and to develop a connection with local cultural loss via prosthetic memories and acts of consumption. Starbucks’s Bing Sutt renders what was previously only narrativized into an inhabitable space, which allows me to feel that I am prosthetically developing a relationship with local cultural memories and losses that I have never truly experienced. However, as I sat in the booth inside Bing Sutt Corner and sneered at the free coffee mooncake samples the barista just handed me, I felt confident—smug, even—that I possessed enough cultural cachet to “see through” the corporation’s glocal marketing strategies. The tension and incongruence revealed here deters me from making a sweeping and harsh critique of Starbucks for profiting from the appropriation and production of local nostalgic kitsch; instead, I have come to consider the complex ways in which Starbucks and consumers use each other to produce and occupy the subject positions they desire. Although such positions may not foster substantive political critique, we cannot dismiss the agentic role consumers and their desires play in relation to the glocalizing strategies of TNCs, including the inculcation of prosthetic memories.

Social Media Analysis

Although I have conducted on-site observations to see how the space is used by regular patrons, my observations alone cannot demonstrate how consumers make use of Starbucks’s Bing Sutt to make meaning and craft identities. I am also interested in the consumer desires and subjectivities that Starbucks’s Bing Sutt produces and encourages by creating conditions that impart particular cultural and political meanings to the consumption of products. To examine the kinds of reactions elicited by the space and how patrons represent their experience, I survey travel blogs and images on Instagram that are either tagged at the location or carry the hashtag “Starbucksbingsutt” and/or its Chinese equivalence.

These data reveal that Starbucks’s Bing Sutt is extremely popular among tourists from East and Southeast Asian countries—particularly South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Malaysia. Of the 447 Instagram images that surfaced during my search, most use filters to portray the Bing Sutt Corner in a highly stylized and romantic manner. Most images feature Starbucks drinks with the company’s signature logo prominently present. By turning the store into a touristic spectacle, Starbucks prompts consumers to participate in the social marketing of the brand, which increase its brand presence on social media networks. What is more significant, however, is that by displaying the Starbucks logo, these visitors are constructing and occupying the valued subjectivity of a cosmopolitan consumer—a subjectivity associated with privilege, wealth, boutique multiculturalism, and whiteness. My findings suggest that although our impulse as rhetoricians is to interrogate Starbucks’s Bing Sutt,and incongruent spaces like it,through “a critic’s ‘odd viewership’” (Blair and Michel 68) and critique the space’s “symbolic, situational, and generic adequacy” (Blair and Michel 67) in relation to the redeployment of cultural memory, we also should attend to how other audiences experience the space and the kinds of meanings and identities they construct through such consumption and embodiment.

In addition to romantic shots of the décor, selfies of patrons posing with their Starbucks drinks and snacks are also prominent on social media platforms. I expected local Hong Kong visitors to offer more reflective and culturally specific discussions of the Starbucks Bing Sutt than tourists from other locations, but I discovered that the identities constructed and performed through these social media postings are largely the same regardless of cultural and national backgrounds. Almost all of the reviews, blog posts and Instagram images that I have examined describe the Bing Sutt Corner as “nostalgic” without any further qualifiers or reflections. What is prominent and continuously reinscribed, however, is the patrons’ affection towards Starbucks and their appreciation for the conceptual incongruence behind the Bing Sutt Corner. For instance, , many Instagram users juxtapose the local baked goods they purchase at the coffee shop with signature Starbucks drinks. Many then remark on the “uniqueness” of this act of consumption and encourage others to experience the novelty and kitschiness of the store. Lacking in these images and descriptions are reflections that are personal and culturally specific. Although Starbucks markets the corporation’s Bing Sutts one-of-a-kind, consumers who represent the space on social media rarely deviate from the implicit genre conventions of Starbucks Instagram images that create a special relationship between the consumers and the brand.

As one of the most popular global brands, Starbucks currently has 11.3 million followers and 24,365,261 tagged posts on Instagram. Posting Instagram images of one’s Starbucks drink—particularly if it is a limited seasonal drink like the Pumpkin Spice Latte or the Unicorn Frappuccino—has become a recognized cultural phenomenon in the U.S. (Johnson; O’Connor). Most images center on the drink itself with the company’s logo prominently displayed; consumers also utilize filters to render their Starbucks experience romantic, pleasurable, and even dreamy. The images posted by Asian visitors of Starbucks’s Bing Sutt, in other words, cohere with other Instagram images produced and circulated by Starbucks’s transnational base of consumers—particularly those in the U.S.. As Banet-Weiser posits, participating in brand culture through social media allows consumers to develop entangled relationships not only with the brand but also with other consumers. In this case, participating in the dominant brand culture on Instagram without disrupting the dominant brand narrative acts as a platform for Asian consumers to temporarily suspend their difference and occupy a white, middle-class subject position like their peers in the U.S. who first populated the Starbucks hashtag.

By Instagramming their Starbucks experience through specific aesthetics, American and Asian consumers participate in a community that helps promote the brand’s image while they concretize their desired subject position as privileged, “worldly” cosmopolitans. The demographic of Instagram users overlaps with Starbucks’s target consumers: they are between the ages of 19 to 29 with members of households that make over $75,000 a year (qtd. In O’Connor). Together, the consumption of Starbucks and the usage of Instagram represents a coveted, privileged subject position. Similar to pictures of the Bing Sutt Corner, most images with a Starbucks hashtag rely on the app’s built-in filters to render the company’s coffee drinks aesthetically pleasing—romantic, even. At the same time, Starbucks actively encourages and participates in the marketing of such genre conventions: the posts released by the company, for example, often mirror the composition and style of images produced by popular Instagram users in the U.S. (O’Connor). By doing so, the corporation ensures a consistent brand image that boosts the aesthetics of an up-scale coffee culture while encouraging avid participation and loyalty from its customersBy posting images of the one-of-a-kind coffee shop while adhering—either intentionally or unintentionally through socialization—to genre expectations, Asian visitors of Starbucks Bing Sutt are able to assume and perform privileged, cosmopolitan whiteness.

Since Starbucks as a brand has come to represent a transnational, middle-class, cosmopolitan subjectivity (Mathieu), the Bing Sutt Corner—nestled tightly within it—encourages and rewards visitors who subscribe to such an identity. As Grewal points out, American corporations like Starbucks that have a large transnational consumer base often practice market segmentation to produce and target different identities. Through this process, multiculturalism becomes “a neoliberal corporate project of selling goods to a transnational consumer culture connecting many national identities” (91). By deploying boutique multiculturalism through the inculcation of prosthetic memory—coupled with “some aspect of Americannness” (Grewal 96)—Starbucks manages to create transnational consumer subjects who are “able to recognize ‘global brand names’ even if this recognition was incorporated into a unique cultural environment” (Grewal 92). What is being actively cultivated and encouraged within the transnational consumerist culture, in other words, is not particular cultural narratives and identities but knowledge of popular Western brands and the privileged subject positions they represent. The potent transnational brand recognition and loyalty among transnational consumers allows Starbucks to repurpose elements of local cultural memories without compromising the company’s brand and its connection with middle-class whiteness. The inculcation of prosthetic memories, in other words, is indeed effective in cultivating a shared identity across difference—except that it is an identity that promotes a neoliberal, and seemingly apolitical, subjectivity of cosmopolitan consumerism.

Conclusion

Starbucks’s Bing Sutt is a successful project for the corporation because it renders local cultural memories into a consumable and playful experience that may otherwise be alienating and esoteric to some. Moreover, it does so in a way that highlights rather than obscures the brand and its overarching ethos. The maintenance of brand image is important not only for the company but also for the consumers. For many consumers in non-Western contexts, the white, cosmopolitan subject position they desire can only come from consumption of the brand’s products. Although our impulse as rhetoricians may be to critique TNCs like Starbucks for their selective commodification of collective memory, this article demonstrates that we should also consider how people in postcolonial, non-Western contexts make use of such branding projects to assert their transnational subjectivity and agency.

- 1. For a more detailed discussion on how the red-white-blue canvas has been deployed as a symbol of collective identity among local Hongkongers, see Nga-ying Liu’s work.

- 2. The annual, large-scale civil rights protests on July 1—the day on which Hong Kong was returned to China in 1997—are indicative of the political tensions between the mainstream Hong Kong public and the Chinese state. The tension culminated into the Umbrella Movement in 2014, during which protesters occupied central areas of the city demanding universal suffrage for the SAR’s Chief Executive.

- 3. The direct translation of “paper cakes” is “paper wrapped cake.” It is a small, cone-like yellow sponge cake wrapped in wax paper.

- 4. In his book Suburban Dreams: Imagining and Building the Good Life, Dickinson examines how chained Italian restaurants allow middle-class American suburbanites “a circumscribed but affectively powerful mode for experiencing the world beyond the suburb’s gates” (98). Although I was no white suburbanite in the U.S., the affective charge and familiar comfort that Starbucks’s Bing Sutt offered me was similar to the consolation chained restaurants offer them.

Aiello, Giorgia and Greg Dickinson. “Beyond Authenticity: A Visual-Material Analysis of Locality in the Global Redesign of Starbucks Stores.” Visual Communication, vol. 13, no. 3, 2014, pp. 303–21.

Au, Pei-sheung. “The Story of Old Bing Sutt.” Apple Daily, 5 Sept 2014, http://hk.apple.nextmedia.com/supplement/food/art/20140905/18855741.

Au-yeung, Allen. “Demolition Work Begins on Historic Hong Kong Pawn Shop Slated to Become Commercial Tower.” South China Morning Post, 27 July 2015, http://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/health-environment/article/1843855/demolition-work-begins-historic-hong-kong-pawn.

Banet-Weiser, Sarah. AuthenticTM: The Politics of Ambivalence in a Brand Culture. New York UP, 2012.

Blair, Carole and Neil Michel. “Commemorating in the Theme Park Zone: Reading the Astronauts Memorial.” At the Intersection: Cultural Studies and Rhetorical Studies, edited by Thomas Rosteck,. Guilford Press, 1999, pp. 29-83.

Blommaert, Jan and Piia Varis. “Enough is Enough: The Heuristics of Authenticity in Superdiversity.” Linguistic Superdiversity in Urban Areas: Research Approaches, edited by Joana Duarte and Ingrid Gogolin, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2013, pp. 143-160.

Bruner, Edward. Culture on Tour: Ethnographies on Travel. U of Chicago P, 2004.

Casey, Edward. “Public Memory in Place and Time.” Framing Public Memory, edited by Kendall Philips, U of Alabama P, 2004, pp. 17-44.

Chatterjee, Partha. The Nation and Its Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial Histories. Princeton UP, 1993.

Chow, Chung-ming. “Bing Sutt Strives for 50 Years.” Oriental Daily, 21 Apr. 2010, http://orientaldaily.on.cc/cnt/lifestyle/20100421/00321_001.html.

DeChaine, D. Robert. “Ethos in a Bottle: Corporate Social Responsibility and Humanitarian Doxa.” The Megarhetorics of Global Development, edited by Rebecca Dingo and J. Blake Scott, U of Pittsburgh P, 2012, pp. 75-100.

Dickinson, Greg, et al. editors. Places of Public Memory: The Rhetoric of Museums and Memorials. U of Alabama P, 2010.

Dickinson, Greg. “Joe’s Rhetoric: Finding Authenticity at Starbucks.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 32, no. 4, 2002, pp. 5–27.

---. Suburban Dreams: Imagining and Building the Good Life. 2nd ed., U of Alabama P, 2015.

Dingo, Rebecca, et al.. “Toward a Cogent Analysis of Power: Transnational Rhetorical Studies.” JAC, vol. 33, no. 3-4, 2013, pp. 517-28.

“Duddell Street—Central.” Starbucks, http://www.starbucks.com.hk/coffeehouse/store-design/duddell-street.

Fish, Stanley. “Boutique Multiculturalism, or Why Liberals Are Incapable of Thinking about Hate Speech.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 23, no. 2, 1997, pp. 378–95.

Grewal, Inderpal. Transnational America: Feminisms, Diasporas, Neoliberalisms. Duke UP, 2005.

In-Store Display. Starbucks Bing Sutt, Shop M2, Mezzanine Floor, Baskerville House, 13 Duddell Street, Central.

Johnson, Lauren. “Starbucks’ Pumpkin Spice Lattes are Killing it on Instagram: Fall-themed Posts Boost ‘Likes’ by 493%.” AdWeek, 8 Sept. 2016, http://www.adweek.com/digital/starbucks-pumpkin-spice-lattes-are-killing-it-instagram-173351/.

Liu, Nga-ying. Red-white-blue and Hong Kong Installation Art. MPhil Thesis, Lingnan University, 2011.

Philips, Kendall and G. Mitchell Reyes, editors. Global Memoryscapes: Contesting Remembrance in a Transnational Age. U of Alabama P, 2011.

Kaplan, Caren. Questions of Travel: Postmodern Discourses of Displacement. Duke UP, 1996.

Landsberg, Alison. Prosthetic Memory: The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture. Columbia UP, 2004.

Mathieu, Paula. “Economic Citizenship and the Rhetoric of Gourmet Coffee.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 18, no. 1, 1999, pp. 112–27.

Sturken, Marita. Tourists of History: Memory, Kitsch, and Consumerism from Oklahoma City to Ground. Duke UP, 2007.

O’Connor, Clare. “Starbucks and Nike are Winning Instagram (and your Photos are Helping).” Forbes, 13 Feb. 2014, https://www.forbes.com/sites/clareoconnor/2014/02/13/starbucks-and-nike-are-winning-instagram-and-your-photos-are-helping/#6e4ab84831b0.

Olalquiaga, Celeste. The Artificial Kingdom: On the Kitsch Experience. U of Minnesota P, 2002.

Ong, Aihwa. Flexible Citizenship: The Cultural Logics of Transnationality. Duke UP, 1999.

Spencer, Richard. Hong Kong to Lose Historic Pier. 1 Aug. 2007. Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/1559157/Hong-Kong-to-lose-historic-pier.html.

Vickers, Edward. In Search of an Identity: The Politics of History as a School Subject in Hong Kong, 1960s-2005. Comparative Education Research Centre, Hong Kong University, 2007.

Yam, Shui-yin Sharon. “Affective Economies and Alienizing Discourse: Citizenship and Maternity Tourism in Hong Kong.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 46, no. 5, 2016, pp. 410–33.

---. “Education and Transnational Nationalism: The Rhetoric of Integration in Chinese National and Moral Education in Hong Kong.” Howard Journal of Communications, vol. 27, no. 1, 2016, pp. 38–52.