April O’Brien, Sam Houston State University[1]

(Published May 11, 2020)

Geography is therefore the art of war but can also be the art of resistance if there is a counter-map and a counter-strategy.

– Edward Said, Peace and Its DiscontentsWhile we follow, observe, and create methodological guidelines to create knowledge that is generalizable, transparent, and systematic, in doing so, we often miss or purposefully elide connective heuresis—the ‘finding and creating’—that emerge from our methods.

– Jennifer Clary-Lemon, “Serendology, Methodipity”

According to Jim Enote, traditional Zuni farmer and director of the A:shiwi A:wan Museum and Heritage Center, “Modern maps don’t have a memory” (Loften and Vaughan-Lee). Disrupting Western practices of place and geography, Enote and several Zuni artists and storytellers have created a series of counter maps, which are decolonized maps “that bring an indigenous voice and perspective back to the land . . . challenging the arbitrary borders imposed on the Zuni world.” These practices of counter-mapping illustrate a critical spatial perspective, which is a way of understanding (a) how spaces and places are affected by social, cultural, ideological, and rhetorical contexts, and (b) how those contexts are in turn influenced by spaces and places.[2] In other words, space produces meaning, and meaning is produced by space. As Doreen Massey explains, space is “the product of interrelations,” and these relationships point back to dynamics of power and agency (9). In the words of Natchee Blu Barnd, “Any dominant form of space or spatiality stands as, and is, power, as it structures particular values about, views of, and practices within the world and reinforces these structures by shaping encounters to match that world” (13). Thus, critical spatial perspectives reveal inequitable power relationships in the ways space is used, remembered, and communicated.

While rhetoric and writing studies has taken up the study of spaces and places in multiple ways, this article introduces a critical spatial method-methodology called chora/graphy. Chora/graphy is an extension of Gregory Ulmer’s choragraphy, a theory of metaphysical invention in spaces and places.[3] Although chora/graphy loosely practices spatialized invention, it is foremost a method-methodology that reorients place and public memory as a measure to resist any controlling space/place narratives and meaning-making practices that ignore other cultural histories and considerations. Correspondingly, this article highlights the exigence for examining issues of race, place, and public memory; uncovering dominant white-centric narratives and meaning-making practices; and creating opportunities for multiply marginalized narratives to circulate in public memory.

In what follows, I offer chora/graphy as what Jennifer Clary-Lemon would call a method-methodology: that is, as both a methodology and a method. In one sense, it works as a theory that guides my research and informs my analysis; yet, it also functions as a fluid, loosely-arranged set of research methods. In terms of theory, this method-methodology puts the concept of chora into conversation with perspectives and practices in cultural geography and indigenous rhetorics to interrogate spaces and places. Furthermore, chora/graphy builds on Ulmer’s choragraphy to make overt connections between chora, critical spatial practices and cartographies, and counter-mapping. These connections help establish avenues for circulating stories and memories that have been marginalized and minoritized by Western settler narratives. As method, chora/graphy is affective, embodied, and nonlinear. It illustrates, in Clary-Lemon’s words, how “our methods are not untroubled and often do not reflect the rational idea of systemicity . . . we may establish them by accident, by familiarity, or by targeted expertise. Or we may establish methods by dwelling—by matching up what we know with what we make—even methodological work—often begins with the body” (206). Likewise, Lisa King et al. contend that “our discipline’s tendency to prioritize so-called objective approaches to knowledge . . . discourages the inclusion of American Indian voices,” and, as I argue further, other marginalized perspectives, methods, and practices (4). As scholars of rhetoric and writing studies, we are compelled to use respected time-tested research methods (qualitative, quantitative, mixed-methods), and although these methods have an important place in our field, I also argue that there is a need for more invention, creation, and emotion in our methods as a complement to these other (perhaps more precise) practices. Adopting methods that allow researchers to attune to the world with their bodies and emotions allows, if not invites, them to consider problems that are messy, blurry, and not easily analyzed by approaches that require precision, efficiency, and measurability. As Clary-Lemon writes, “While we follow, observe, and create methodological guidelines to create knowledge that is generalizable, transparent, and systematic, in doing so, we often miss or purposefully elide connective heuresis—the ‘finding and creating’—that emerge from our methods” (209). Chora/graphy especially acknowledges the researcher’s embodied responses, and it critically attunes practitioners to those moments of connective heuresis. Or, put in more expansive terms: instead of disassociating my physical body from spaces, places, and objects, chora/graphy compels me to feel and experience.

In this article I use chora/graphy as a method-methodology, and as I do so, I argue for alternative explorations of race, place, and public memory in rhetoric and writing studies. More specifically, bringing Black feminist geography and indigenous studies into the conversation adds greater granularity to the what/how of rhetorical inquiry and research. Scholars in rhetoric and writing studies have studied the relationship between place and writing practices (Dobrin; Reynolds), critiqued constructions of place within a framework of environmental justice (Sackey), widened the scope of the rhetorical situation to a place-based ecological practice (Edbauer), and analyzed the intersection of public memory and space/place (Blair; Boyle and Rice; Dickinson et al.; Sanchez; Tell). In related fields, scholars ranging from Gloria Anzaldúa to Edward Soja have drawn our perspective back to hegemonic power dynamics within spaces and places, including how difference is articulated and how spaces and places are ideological and rhetorical (de Certeau; Lefebvre; Sibley). In addition to this scholarship, which represents mostly Western ways of knowing, chora/graphy is inspired by place-based indigenous meaning-making and African American rhetorics, including Enote’s collaborative mapping project with Zuni artists that reorients identity, history, and culture (Loften and Vaughan-Lee); Tamara Butler’s BlackGirlLand; and the collaborative BlackLandProject. In this article, I bring principles and perspectives from rhetoric and composition and writing studies (RC/WS) into conversation with Black feminist geographies and indigenous studies.

I forge this methodological plan for three reasons. First, my citation practices are an ideological decision that reflect my desire to highlight diverse voices and viewpoints surrounding conversations about public memory, race, and place.[4] Second, the scholarship outside the immediate field of RC/WS adds greater specificity to critical considerations at the core of this work. For example, drawing from Black feminist geographies via Katherine McKittrick allows me to engage with contemporary issues on race and place, which in turn establishes a richer set of considerations for praxis. Third, the application of the theory offered here, chora/graphy, takes place in a predominantly Black community in South Carolina’s upstate; in this undertaking, as I support the community’s desire to reclaim stories and memories that have been marginalized and minoritized by Western settler narratives, I cannot simply use the same white, male, patriarchal voices, for doing so would only impose more colonial violence on the community. Likewise, as a white settler scholar, I need to be cautious that I do not perpetuate rhetorical violence through my research.

In this essay, then, I center chora/graphy as a critical spatial method-methodology that reorients the study of race, place, and public memory by exposing dominant cultural narratives and replacing them with community stories that have been historically marginalized. I make several moves toward that goal. First, I define chora/graphy and situate it within contemporary discussions about chora. Second, I describe critical spatial theories and practices in Black feminist geographies, indigenous studies, and RC/WS—describing their individual and collective implications and considerations for chora/graphy. Third, I argue for chora/graphy as a method-methodology that uses personal memory, affect, and story as a creative, loose set of practices. Fourth, I model chora/graphy via case study, using Pendleton, South Carolina, a small town in South Carolina’s Upstate, as a critical test object. Finally, I consider the implications for chora/graphy for writing and rhetoric research.

Chora/graphy: A Definition and Examples

As a method-methodology, chora/graphy is a critical construction that is rooted in chora. Although Indra McEwen has traced the Pre-Socratic beginnings of chora back to Homer and Hesiod (Rickert 254), chora, as a rhetorical concept, did not receive extensive attention in rhetoric and writing studies until rather recently (Arroyo; Carter; Clary-Lemon; Rickert; Santos and Browning). Chora is an ancient Greek word for space or place, and Plato considered it as a “third kind,” a bastard discourse that is neither rational nor definite (40e). Chora is difficult to define; further, to define chora is to constrain it and diminish its potentiality. Rather than define it, I trace two threads of chora: its sensory/affective component and its inventional capacity. As Sarah Arroyo writes, chora, as a third kind or meaning, “can only be felt”; it resonates and vibrates within our bodies (64). In E.V. Walter’s words, chora is connected to a space’s energies, passions, myths, fantasies, biographies, and histories—its “expressive space” (9). This embodied and affective element of chora compels us to deal in the material: How does this place make me feel? How does my body react to this space? Related to this notion of feeling and sensation is the second thread—chora as invention. This inclusion of invention moves chora from a philosophical theory into rhetorical inquiry and practice.

It is Ulmer who ultimately re/envisions chora as something we can do.[5] He calls this practice choragraphy, or place-as-invention (doing place). Choragraphy is a way of mapping an individual’s sense of place and memory; thus, it is subjective and open to interpretation (Ulmer 39). Doing choragraphy means that we move “in-between”—to the liminal space between the material and metaphysical world (Arroyo 68). According to Ulmer, there is no recipe for choragraphy (41); rather, choragraphy creates an environment for individuals to “feel an invention that is both sparked by a punctum and remembered by the body” (Arroyo 62). I will return to this concept of punctum later in this article, but for the purpose of understanding choragraphy, punctum refers to that which pricks or stings our consciousness. To do choragraphy, one must see relationships and networks within memory, space, and place—and rather than logically examine these relationships, we must be attuned to the punctum, to the pricks and stings, to make something from these felt experiences.

Whereas Ulmer’s choragraphy still mostly deals with metaphysical invention in spaces and places, here I want to offer chora/graphy as far more embodied and material than Ulmer’s germinating construct. That is, my chora/graphy differs from Ulmer’s choragraphy in key ways. First, Ulmer’s work with choragraphy is largely grounded in inventional practices. Chora/graphy, though, recognizes “graphy” from the Greek graphia, (which means “writing”); consequently, chora/graphy with a slash is a writing of the chora that draws from choragraphy, Black feminist geographies, and indigenous studies. Second, Ulmer’s work with choragraphy aims to inspire practitioners to discover relationships and networks. Chora/graphy, on the other hand, is a critical spatial method-methodology that is action-oriented and functions to resist dominant cultural narratives; it is specific and intentional in its focus on social justice, diversity, and inclusion. By using story, community engagement, and counter-mapping, chora/graphy redresses inequities through a critical examination of race, place, and public memory. I will describe a variety of models that incorporate traits of chora/graphy, and through a rhetorical engagement of these models, I will identify their fundamental features and then describe their implications and considerations for chora/graphy. In doing so, I will intentionally use story and relationality because, as Malea Powell et al. argue, “all cultural practices are built, shaped, and dismantled based on the encounters people have with one another within and across particular systems of shared belief” (1.2). As I describe chora/graphy as a method-methodology, the totality of these theories, stories, and descriptions are meant to be loosely instructive. In short, I am explaining and demonstrating at the same time.

Theories and Examples

Cultural geography and Black feminist geography—subfields within geography studies that focus on the interaction between people and place—are particularly instructive for chora/graphy because they theorize and apply critical spatial practices/perspectives. In particular, since Peter Jackson’s edited collection Race and Racism: Essays in Social Geography scholars in geography studies have grappled with how identities of race, gender, and class are linked to place and space. Cultural geographers offer critical mapping strategies to visualize, analyze, compare, and examine spatialized inequalities (Delaney; Jackson; Kobayashi and Peake; McKittrick; Nelson). In their forthcoming article on rhetorical countermemory, O’Brien and Sanchez highlight cultural geographer Stephen Legg’s “sites of countermemory,” a concept that they trace in the American South and Texas. The authors extend Legg’s discussion of countermemory into rhetoric and writing studies, and this thread of counter-theories is emphasized in this essay as well.

Although not explicitly endorsing a counter-theory of cultural geography, Katherine McKittrick argues that “Black matters are spatial matters” (xiii).[6] This assertion grounds Black feminist geography, an intersectional branch of cultural geography (xiii). Black feminist geography examines relationships between gender, race, and place and argues that scholars cannot separate place from considerations of race (and vice versa). Race and place are intrinsically linked. The 2018 American Association of Geographers (AAG) Annual Meeting choose Black Geographies as its theme, with the theme committee providing the following statement about race and place:

Practices of Black life, resistance, and survival are inseparable from the production of space. Decades of work within and beyond the discipline have centered Black Geographies frameworks in re/considering humanness, cities, regional blocs, social movements, faith, identities, and structural inequalities. Black-oriented epistemologies operate in resistance to reductionary claims on Black spaces, places, theories, and methods. (Black Geographies)

Scholars in Black feminist geography seek to redefine what counts as knowledge and which types of research circulate in the larger field of geography. These researchers continue to expand a canon that has been dominated by white cis-male scholars by becoming more interdisciplinary and drawing from Black feminist and decolonial studies. In addition to finding a “sense of place,” Black feminist geographers pursue a “Black sense of place” (Massey 149; McKittrick 949).

Likewise, research in indigenous studies provides a vital perspective that centers considerations of land, decoloniality, and memory. Most importantly, though, indigenous studies exists in tension alongside settler colonial geographies—its presence demonstrates the need for counter-geographies that proclaim, “we [indigenous people] are still here” (Blu Barnd i). By fostering ethical, accountable, and reciprocal engagement and research with indigenous communities, scholars in indigenous studies value the spatial practices of tribal groups and seek involvement from these communities in place-based projects (Blu Barnd; Loften and Vaughan-Lee; Pappan).

A handful of scholars in rhetoric and writing studies have examined the implications of race, place, and memory and, in doing so, have laid the foundation for further study (Butler; King; Poirot and Watson; Sanchez; Sanchez and Moore; Tell). For example, in their analysis of Charleston, South Carolina’s problematic tourism industry, Kristan Poirot and Shevaun Watson recommend that more scholars “develop ways to read” the relationship between race, place, and memory, especially through the lens of tourism (112). Poirot and Watson’s statement is salient and highlights the need for theories and practices outside of rhetoric and writing studies as we develop a nuanced and inclusive vocabulary about race, place, and memory. The scholarship in Black feminist geography and indigenous studies opens opportunities for us to be attentive to land, decoloniality, and memory, as well as matters of race, racism, and space/place. These theories and methods help create a framework for chora/graphy by problematizing whitestream and other dominant narratives of place and memory, by using story and community engagement to recast place and memory, and by promoting action-oriented research and practice. In what follows, I cite three projects for the purpose of drawing out central features that inspire and inform chora/graphy, as well as to demonstrate how scholarship outside of rhetoric and writing studies adds to the granularity of these conversations.

As a scholar of African American and African Studies, Tamara Butler’s The BlackGirlLand Project is a collaborative project that links Black women, nature, land, and rural spaces (“Honoring”). Butler’s experiences as a Black woman with deep ties to the land inspires her research:

As a Black woman who grew up on a South Carolina Sea Island, [I am] aware of how sociocultural, economic and racial demographic changes in the community are erasing some of the Island’s histories. Therefore, The BlackGirlLand Project attempts to preserve some of those histories through oral history interviews with Black women living on the South Carolina Sea Island of Johns Island and Black women who once lived on (and responsible for caring for) farmland. (“The BlackGirlLand Project”)

Butler argues that “Our [Black lives] liberation requires cartographic knowledge,” and BlackGirlLand seeks to preserve the lived experiences of Black women in the South Carolina Sea Islands (“BlackGirlPraxis”). Her work also extends into the classroom, where she teaches courses that challenge students to constellate relationships between people of color and land, environment, and nature. From Butler’s research and pedagogy, we see the importance of story and relationality as she traces her family’s roots on St. Johns Island in South Carolina and as she discusses the differences between what is publicly circulated about the Island’s Black histories and the stories that are told in the churches, community centers, and homes. For example, Butler cites “The Progressive Club,” an organization began by Septima Clark and others to educate Black residents to read and write so they could pass the test for voter registration in the mid-twentieth century. Although she was never taught about this organization in school, she learned about it through her family and community (“Honoring”). The fact that Butler had to learn of these histories through The Progressive Club rather than her general education, which should have some connection to local history, suggests not only a gap in the educational structure but also reflects one of the very problems to which chora/graphy hopes to respond: the erasure of (or, at minimal, lack of exposure to) non-white histories, organizations, and cultural practices. Butler’s research demonstrates the exigency for chora/graphy and other critical spatial method-methodologies: repeatedly, across the United States, the public memory of black and indigenous people of color (BIPOC) has been systematically erased and/or white-washed. Thus, scholars concerned about issues of race, place, and public memory should be participating in “action-oriented research” that redresses inequalities like the one above (Jones and Walton 242).

Another example is Black/Land Project, a collective, digital engagement that “identifies and amplifies conversations happening inside Black communities about the relationship between Black people, land, and place in order to share their powerful traditions of resourcefulness, resilience, and regeneration” (“The Black/Land Project”). Black/Land Project’s organizers include community leaders and academics in a variety of fields including critical race studies, indigenous studies, public policy, and others. As the executive director of Black/Land Project, Mistinguette Smith seeks to “identify and amplify the current critical dialogues surrounding the relationship between Black people and land,” whether the locale is the Alabama Black Belt or a Detroit neighborhood (“About Us”). In addition to their community collaborations and speaking engagements, much of Black/Land Project is about sharing stories. On their website is a collated series of stories from the organizers and other participants. Like BlackGirlLand Project, Black/Land is collaborative and draws from story; for example, each blog post presents a different story from varied authors that explores the complexities of race and place and virtually maps those relationships. One of the key elements Black/Land Project provides is the need for and value of participatory community-based research within space-based scholarship. The project, like so many others, helps situate the significance of community involvement and community investment in the process and outcomes.

Along with Butler’s and Smith’s work that focuses on the intersection of Black individuals, memory, and place, is Jim Enote’s community work, which demonstrates the link between indigenous studies, memory, and place. Enote, a traditional Zuni farmer and director of the A:shiwi A:wan Museum and Heritage Center, partnered with Zuni artists, elders, and council members to create maps that challenge Western ways of knowing and making.[7] Their maps, what they refer to as “counter maps,” are intended, as Enote explains, to “reclaim the names of Zuni places and depict the land of the A:shiwi as they know and see it . . . with culture, story, and prayer . . . [because] modern maps do not have a memory” (Loften and Vaughan-Lee). The maps that the artists created look nothing like Western maps or atlases. Rather, they are composed of colorful, textured images and stories.[8] One of the artists, Ronnie Cachini, a Zuni medicine man for the Eagle Plume Down Medicine Society and a head rain priest, created a map called Ho’n A:wan Dehwa:we (Our Land). Cachini explains what makes Zuni maps unique: “A conventional map takes you to places—it will tell you how many miles and the fastest route. But the Zuni maps show these significant places that only a Zuni would know.” Cachini adds, “especially if you’re in a religious leadership position: you see the prayers that we say, the prayers that we hold . . . I incorporated a basket and prayer sticks to signify that” (qtd. in Loften and Vaughan-Lee).

Cachini’s contention directly refutes the notion that maps represent Truth and objectivity:

[Modern maps] are widely assumed to convey objective and universal knowledge of place. They are intended to orient us, to tell us how to get from here to there, to show us precisely where we are. But modern maps hold no memory of what the land was before. Few of us have thought to ask what truths a map may be concealing, or have paused to consider that maps do not tell us where we are from or who we are. Many of us do not know the stories of the land in the places where we live; we have not thought to look for the topography of a myth in the surrounding rivers and hills. Perhaps this is because we have forgotten how to listen to the land around us. (Loften and Vaughan-Lee, emphasis mine)

As Enote and the Zuni artists reject maps that circulate a settler colonial narrative, the process of counter-mapping demonstrates the importance of drawing from the community to align social justice practices with mapping practices. Along with some of the similar threads of story and community engagement (which are apparent in Butler, Enote, and Smith's scholarship) is a new concept: counter-mapping. In terms of its theory and practice, chora/graphy draws from these concepts to resist any controlling space/place narratives and meaning-making practices that ignore other cultural histories and considerations. Chora/graphy works to extend the memory of multiple marginalized individuals in specific spaces and places. Although these examples span a variety of disciplinary practices, theories, and frameworks, when presented together they demonstrate key concepts that have the potential to recast the way rhetoric and writing studies investigates race, place, and public memory. Several threads occur in these examples, including the significance of story, community engagement, and counter-mapping that resist dominant cultural stories—these three elements are the components of chora/graphy.

In addition to these three elements of chora/graphy, it is important to recognize and discuss chora’s affective and inventive capacities because chora, as a felt and creative impulse, propels chora/graphy as a method-methodology. As Clary-Lemon writes, “Making, questioning, or inventing methodological choices while considering the roles of memory, place, affect, and the material world positions emotions as generative, as . . . effects that offer a fuller understanding of the messiness of methodology and its rhetorical, choric nature” (210). To understand how affect and emotion operate as generative aspects of chora/graphy’s method-methodology, I turn to Roland Barthes’s theory of punctum.

Taken at face value, Barthes’s theory of punctum is a way to recognize images that prick or wound, in contrast to images of studium that perform a more educational and distancing role in visual rhetorics (26-27).[9] However, when applied in a more expansive context, punctum can be understood as anything seen, heard, felt, or experienced that pierces one’s consciousness. By applying punctum to any material-rhetorical spaces, places, or things, the link between affect and invention is forged (if not foregrounded). Employing punctum in research practices is a deeply personal journey (one that I describe in a narrative), especially when story is/functions as a research practice.[10] In many cases, it is through this function of story that the punctum itself becomes intelligible, where we bring to light the obtuse or “third meaning” (i.e., that element beyond communication and signification) (“The Third Meaning” 52-53). According to Arroyo, the third meaning is something that can only be found in the chora, what she calls a “holey” or sacred space (62). Arroyo, drawing from E.V. Walter, argues that a sacred place is not merely where the “literal remains of the dead ‘remain’”; rather, sacred places have the ability to generate, create, and invent (Arroyo 62; Walter 120).

A Case Study

In what follows, I provide a narrative that describes how I used chora/graphy to analyze specific sites, as well as how those sites function as memory sites in Pendleton, South Carolina. Before I do so, I need to begin with some context about the site of my study. Pendleton, South Carolina is a rural town located in South Carolina’s Upstate. A small, rural town, Pendleton was established in 1790 after forcibly taking the land from the Cherokee nation. The town is 229 years old and, like many historic communities in the US, suffers from historical myopia, especially in the manners in which it represents itself as a heritage tourism destination and how it erases Black history from public memory. The town is also overtly segregated, with the majority of its Black residents residing on the West Side of Pendleton. This historical and spatialized framework is the backdrop for my case study.

Fig. 1: The Village Green in Pendleton, South Carolina. Photo by the author.

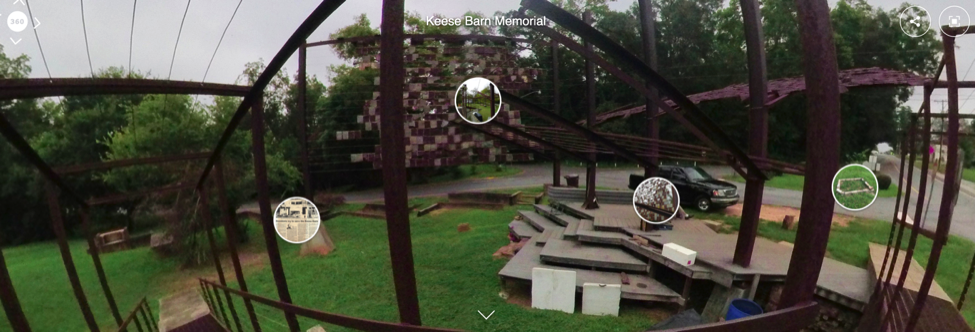

The first time I drove past Keese Barn Memorial, located on the West Side of Pendleton, I was pricked (the punctum). The rusty memorial towers over a large, triangular plot of land, and colorful, plastic Adirondack chairs line the area beneath it. After conducting interviews a few months later, I discovered that the structure was once an antique store and market that provided fresh produce and food, and as a result of the location, the store was a boost to the local economy.[11] Eventually, the store closed, and years later, architecture students from Clemson University tore down the original structure and rebuilt a memorial, using the shingles from the roof and other parts of the original structure to create it. I took photographs of the structure and the surrounding area, including monument-like stones with verses engraved—also a part of the “memorial” that Clemson students created. Aside from a historical marker text located a quarter of a mile around the bend, there is no signage near Keese Barn Memorial to educate visitors about this structure or its historical significance. Once I interviewed local residents, I came to understand that Keese Barn Memorial is viewed as an eyesore in the community—and is a material reminder of what happens when academics create community-engaged projects without actually engaging with the community. In contrast, chora/graphy is a method-methodology that values community relationships, and, in the words of Dustin Edwards, “[i]t requires doing the work of listening to and dwelling with the persistence of colonial erasures while also contemplating possible paths of mutuality in the shared project of working toward collective flourishing” (64).

Around the same time that I encountered Keese Barn Memorial for the first time, I was struck by another image of punctum. This image took the form of a local advertisement for “The Ghosts of Pendleton—Where the Spirits Come to Life!” This sign was advertising nighttime Halloween tours inside the local plantation houses, Ashtabula and Woodburn. Immediately, I was struck by the images and text in this ad, and I started to ruminate about how Pendleton remembers some histories and forgets others, as well as the implications for using contested spaces like plantation houses as tourist destinations. Although this was early on in the research process, as well as the fact that I recently moved to the area, I was almost immediately aware of the disconnection between Pendleton’s public narrative and how it erased and misused black histories. In the time since I was first pricked with “The Ghosts of Pendleton” punctum-image, I created a short video to deal with these questions that I found so concerning.[12] Through the making of this video, I was able to engage with the issues of racism that were represented in Pendleton’s material places and via the town’s public memory. The video explores that initial question that I posed: What would the ghosts of Pendleton say to us if they haunted us today? (O’Brien, “The Ghosts”). Since then, I have continued to trace this “ghostly” punctum in Pendleton and, in doing so, have noted that the ghost narrative is a way to deflect from uncomfortable aspects of the town’s history, including the fact that even though slavery and Jim Crow laws have not been in effect for many years, the town still demonstrates various forms of structural and implicit/explicit racism.

Each October the Pendleton Historic Foundation hosts a Ghost Walk (in other years, this “ghost walk” was housed at the plantation houses, as mentioned earlier) where individuals can “meet prominent Pendletonians who have gone into the beyond” (“Ghost Walk”). Unsurprisingly, when I went on the ghost walk, the “prominent Pendletonians” were all wealthy, white individuals—many of them slave owners. We visited several historic homes and a local church established in the early-nineteenth century—St. Paul’s Episcopal—that two of Pendleton’s most “prestigious” residents once attended, Thomas Green Clemson and Anna Calhoun Clemson. Anna’s “ghost,” played by a local resident, spoke to us that evening in the church and explained the challenges that Anna endured as the daughter of John C. Calhoun and the wife of Thomas Green Clemson. In spite of historical knowledge about the Clemsons, during Anna’s ghostly appearance there was no mention of her husband’s overtly racist beliefs and policies or how her life with Thomas was troubled (Quigley). Instead, the actress playing Anna told light-hearted stories about her life as a wealthy socialite and made several flippant jokes about the Clemson’s large family and the challenges of having a husband who was frequently out of town. In fact, during the entire Pendleton Ghost Walk words like “slavery,” “enslavement,” or “slaves” were never once used. Although Africans were being enslaved in the United States during this time period, the Ghost Walk was performed in such a way as to pretend that these historical moments never existed in the American South. All participants (both actors and the roles they played) were white Pendletonians. Not a single Black historical figure was mentioned, in spite of the fact that various significant Black men and women lived in the town including Benjamin Keese, an entrepreneur and businessman; Jane Edna Hunter, who later founded the Phillis Wheatley Association, a residence for single African American women in Cleveland; and Robert Henry Thompson, a Pendleton Community Center Board member and activist with the NAACP during the mid-20th century (Hassan; Gantt). I felt the noticeable absence of Black and brown narratives and the refusal to address the town’s part in slavery and Jim Crow. Their absence haunted me in a tangible, visceral way.

The tour also included a stop at Gallows Hill, which included the historic home of Col. Joseph Taylor and a large tree on his property where notorious criminals are said to have been hanged during the nineteenth century. Although Taylor’s “ghost” mentioned some of these criminals, he conspicuously avoided mentioning the word “lynching” or any of the Black residents who were lynched without a trial. Gallows Hill was garishly lit up that night with a flood light on the hanging tree, and a sound loop of an eerie, high-pitched scream played as we stood in front of the house. As I stood there with the others in my tour group, I thought again about the other ghosts of Pendleton whose voices we did not hear on the tour. These individuals had been carefully removed from Pendleton’s public memory in favor of a false memory of the Old South. As McKittrick writes, “[A] black sense of place can be understood as the process of materially and imaginatively situating historical and contemporary struggles against practices of domination and the difficult entanglements of racial encounter” (“On Plantations” 949). During this stage of chora/graphy, I began to visualize how Pendleton’s Black history could be “materially and imaginatively” represented in the public sphere as an act of cultural resistance.

These questions about representing Pendleton’s Black history led me to consider how I could use punctum to map erased memory sites. As a result, rather than beginning my research in Pendleton’s archives or through interviews, I allowed those felt spaces, places, and objects to guide my research. Some days, I drove around town, stopping and photographing spaces that captured my attention. Other days, I mapped out areas that I wanted to visit, and I shot video and gathered audio clips. Once I established the sites of focus, I first created a map using Google Maps and placed pins on the punctum spaces, historical marker texts, memorials, and other sites that caught my attention. As I visited new sites and participated in historical tours to gain more information, I used a different Geographic Information Systems (GIS) platform: Google Tour Builder. With this technology, I was both able to add more photos and videos and to create a step-by-step tour that represented mychora/graphic process.[13] The narrative I have described is part of chora/graphy, the part where the researcher (myself, in this case) explores sites of punctum and maps these points using GIS. Next, I describe how I used other elements of chora/graphy including story, community engagement, and counter-mapping.

As a collaborative, community-based project that uses critical-mapping practices, I worked with a local nonprofit organization to collectively create a counter tour called Remembering Black History in Pendleton, South Carolina. As I have already described, Pendleton has carefully curated a public memory that valorizes the Old South, and in doing so, erases the town’s rich Black histories. After I completed my initial examination of the town’s chora, I conducted a series of interviews with various town leaders including the director of tourism, board members from the Pendleton Historic Foundation, and town council members. These initial interviews introduced me to a nonprofit organization called the Pendleton Foundation for Black History and Culture (PFBHC). In my archival research and interviews, I learned how the town represented its history through a white-centric lens. Instead of educating visitors and residents about the implications of slavery and Jim Crow, as well as what the Civil Rights years looked like in Pendleton, the Pendleton Historic Foundation (PHF) hosts social events at the plantation houses.[14] The PFBHC, however, fought to create a Black history and cultural center on the west side of town for twenty-five years without help from the town. The PFBHC was unable to raise the funds, so the original Keese Barn was torn down and Clemson University students created the “memorial.” There was little conversation between the university and the Black residents about this memorial, and the rusty structure was not what the residents expected. They expected a usable space that overtly depicted the legacy of Benjamin Keese, who created a social and economic space in the early-twentieth century right in the middle of Jim Crow South. I cannot overstate the significance of Keese’s impact on the community, from the Saturday night BBQs to the campfires. Keese would mentor young Black men in the community during a time when lynchings were common and violence and injustice surrounded the Black community (Hassan).

I created maps early in this process, and I added to the maps based on personal interviews with community members. From there, I composed a Google Map that visualized unseen boundaries; various routes that individuals took to get to school, work, or stores; sites of memory; historical locations; and other such locations. The Google Map—Mapping Chora in Pendleton—seeks to make visible that which is (or has been) invisible or unknown. From there, I worked with the PFBHC to create an initial framework for a counter tour that was collaboratively composed with community stories and memories—stories and memories that actively resisted the town’s dominant cultural narratives. These stories, like the Zuni maps, “have a memory, a particular truth. They convey a relationship to place grounded in ancestral knowledge and sustained presence on the land” (Loften and Vaughan-Lee). As a white settler scholar without ancestral knowledge and sustained presence in Pendleton’s spaces and places, my role was listener and creator. Collectively, we decided that the tour would be virtual rather than material because it was important that people could engage with the West Side of Pendleton, even if they were not physically in the space. Interactive VR would allow individuals to be immersed into the spaces and places in Pendleton via the click of a few buttons on their keyboard. The sphere of influence is significantly larger than a material site, and because 360-degree footage compels the user to be immersed in the site, there is a deeper engagement with the material spaces virtually.[15]

Fig. 2: Screenshot of Keese Barn Memorial, one section of the VR counter tour.

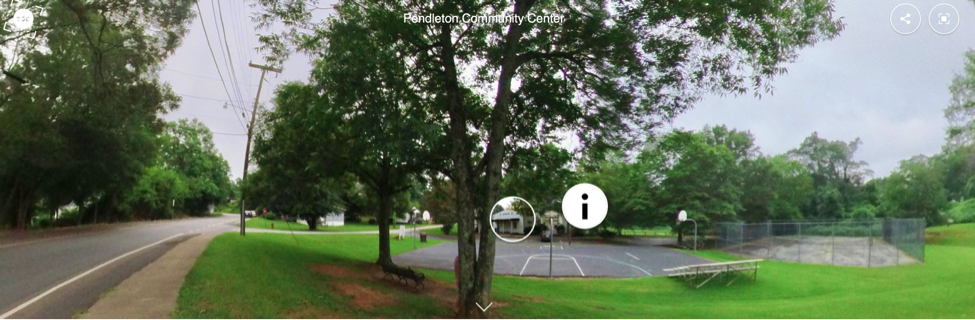

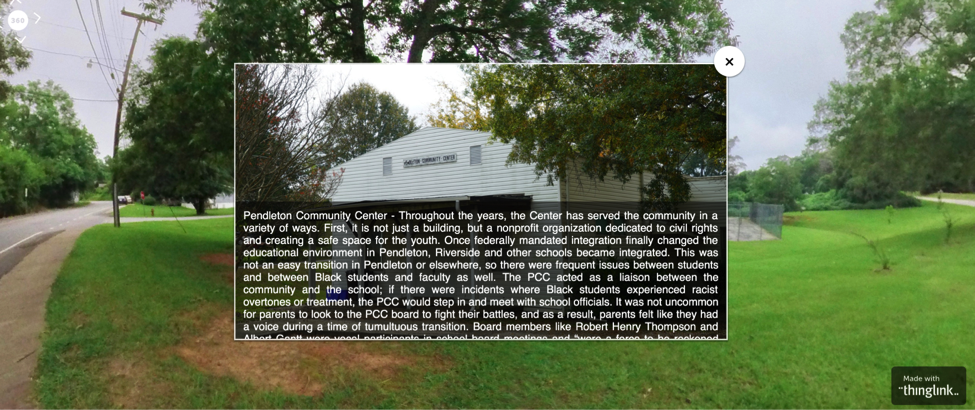

Fig. 3: Screenshot of Pendleton Community Center, one section of the VR counter tour.

I want to circle back to Enote’s counter-mapping and the Zuni artists’ rendering of their land via nontraditional maps. Their maps focus more on story and prayer than on representations of space and place the way Western maps do.[16] I position the counter tour along these same lines. Although it is not a “map” in the traditional sense of the word, the counter tour is nonetheless a counter-mapping project that reclaims Pendleton’s Black histories and depicts the town through the eyes of its Black residents. As a VR counter map, visitors can click around the town’s spaces and places, and each site flows into the next, just as if they were physically moving through the town. Each site is looped and linked with the next so that the experience is seamless. Figure 2 and Figure 3 demonstrate different aspects of the interface: Each 360-degree image is fully interactive, and users can click around the image on various “tagged” circles.

Fig. 4: Screenshot of “tagged” image of Pendleton Community Center. When users click on the circle, a text box and image opens and users can read about the site.

Once the circle is clicked (see Figure 4), a text box emerges with information about the site. This text is derived from interviews, participant observations, and archival research. It’s important to consider how the VR counter tour operates as a disruptive mechanism in Pendleton, a town that emphasizes a nostalgia for the antebellum South and erases people of color from public memory. As a critical spatial method-methodology, chora/graphy in this particular case seeks to expose the effects of whitesplained histories and to collaboratively redress those wrongs to reclaim those histories that have been erased by dominant white culture. The counter-tour used story, community engagement, and counter-mapping to create a new artifact that reflects a portion of Pendleton’s erased narratives. Future iterations of chora/graphy in Pendleton might examine other memories that have been elided.

Implications for Writing and Rhetoric Research

Chora/graphy is a method-methodology that has the potential to bring multiple lines of conversation in Black feminist geography, indigenous studies, and rhetoric and writing into relation. Thus, chora/graphy can further allow the field to re/evaluate decolonial practices in space and place research and perform what Elise Verzosa Hurley calls a “spatially informed praxis” (108). As a white-skinned individual participating in research with people of color, it is imperative that I be vigilant and transparent about power dynamics and to practice ethical community-engaged research. I did this through listening—listening to the perspectives of community members including all the ways that other academics had inflicted colonial violence in this community in recent years. My goal for the counter tour is that it would continue to evolve as more community members collaborate in its production. As that process occurs, I will recede into the background, and the community’s stories will circulate. Without this mindset, though, projects can quickly become settler colonialism in action.

As one of many critical spatial methods and methodologies, chora/graphy is a way of knowing that “require[s] a shift in our thinking” (Hurley 106). This particular shift in thinking provides three major impacts in rhetoric and writing studies. First, this method-methodology opens opportunities for more fluid, embodied methods and methodological practices. It likewise allows us to be attentive to other types of adaptive and emotional theories and practices. Second, chora/graphy demonstrates a more inclusive episteme by bringing Black feminist geography and indigenous studies into a conversation that has been largely dominated by white male scholars. These ways of thinking also add greater granularity to the what/how of rhetorical inquiry and research. Finally, chora/graphy accounts for notably different kinds of bodies operating in diverse kinds of (rhetorical) relations to space/place considerations, or in Sara Ahmed’s words: “To share a memory is to put a body into words” (23). This is my hope for rhetoric and writing studies: that we would include more bodies and more memories that have previously been erased.

[1] I want to thank Laurie Gries, one anonymous reviewer, and especially Justin Hodgson for their helpful feedback. The revision process was considerably less intimidating because of their kindness and support. Also, although this article was initially written in South Carolina on Cherokee land, I completed the revisions in southeast Texas on Atakapa land.

[2] Scholars define the terms “space” and “place” in various ways, but I view places as regions that are defined by boundaries and spaces as non-defined areas. I often use these terms interchangeably, though, because the most ancient word for space/place is chora. For more on space and place, see Martin Heidegger’s “Building Dwelling Thinking,” Edward Soja’s Thirdspace, Michel de Certeau’s The Practice of Everyday Life, and E.V. Walter’s Placeways.

[3] Greg Ulmer’s choragraphy is a theory and practice that positions space and place as fluid, metaphysical, and open to interpretation. Choragraphy emerged as a result of Ulmer using heuretic invention to reconceive how chora informs place, as well as to examine the scholar’s relationship to place (both materially and metaphysically).

[4] I cannot take credit for any bold citational decisions; instead, I thank participants from the Conference on Community Writing in 2017 who challenged the way I have been taught to cite, as well as Sara Ahmed (in Living a Feminist Life and others) and Rebecca Walton, Kristen R. Moore, and Natasha N. Jones in Technical Communication After the Social Justice Turn. These folx, through their citational practices, have inspired me to re/think whose voices I am circulating.

[5] Ulmer’s conception about chora and choric invention is inspired by Derrida’s scholarship. For more about Derrida and chora, see On the Name.

[6] I want to mention Byron Hawk’s Counter-History of Composition as instructive to scholars in rhetoric and writing studies who are interested in counter-projects of various kinds.

[7] The term “Zuni” is a Westernized name for the A:shiwi, a word meaning “human being.”

[8] The maps can be viewed here: https://emergencemagazine.org/story/counter-mapping/.

[9] In Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida, he explores several photographs that are meaningful to him, and he contrasts them with photos that do not stir him. Some photographs may be historically significant or culturally appropriate, but to Barthes, they are images of studium. On the other hand, some images wound/sting/prick him—these are images of punctum (26-27).

[10] Again, this is not a unique concept but one that has been practiced for thousands of years in various cultural traditions (Driskill; Haas; Thomas King; Powell; Riley-Mukavetz, Wilson). As a white-skinned individual, one way that I can work in solidarity with my colleagues of color is to intentionally cite their work and honor their research practices while not claiming them as my own.

[11] Currently, there are no grocery stores located in Pendleton, and the only place to buy groceries is located a few miles away on the main highway. When the market was located in the West Side, it provided jobs for local residents, as well as fresh produce and groceries without having to leave the local neighborhood.

[12] “The Ghosts of Pendleton,” published in The Journal for Cultural and Religious Theory, is included in the Works Cited below.

[13] The tour can be viewed here: https://goo.gl/pBSs24.

[14] During the research process, the director of the PHF blocked me from speaking with the recently-hired docent for the town’s plantation homes. Apparently, the new docent openly encouraged the PHF to be more honest in its tours and focus more on the town’s Black histories. The PHF director, who was aware of my research project, informed me in an email that she would be the only one who would be responding to my questions.

[15] The VR counter-tour can be viewed here: https://www.pendletonfoundation.net/tour.

[16] The counter-maps can be viewed here: https://emergencemagazine.org/story/counter-mapping/.

“About Us.” Black/Land Project, http://www.blacklandproject.org/about-us. Accessed 2 May 2019.

Ahmed, Sara. Living a Feminist Life. Duke UP, 2017.

Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. 4th ed., Aunt Lute Books, 2012.

Arroyo, Sarah. Participatory Composition: Video Culture, Writing, and Electracy. Southern Illinois UP, 2013.

Blu Barnd, Natchee. Native Space: Geographic Strategies to Unsettle Settler Colonialism. Oregon State UP, 2017.

Boyle, Casey and Jenny Rice, editors. Inventing Place. Southern Illinois UP, 2018.

Butler, Tamara. “Honoring Black Women’s Lives: Documenting Untold Stories.” YouTube, uploaded by Michigan State University College of Arts and Letters, 14 Nov. 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bywbApi5EzA.

---. “BlackGirlPraxis.” Conference on Community Writing, 19 Oct. 2017, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO. Panel Presentation.

---. “The BlackGirlLand Project.” https://tamaratbutler.com/blackgirlland.

Clary-Lemon, Jennifer. “Serendology, Methodipity: Research, Invention, and the Choric Rhetorician.” Serendipity in Rhetoric, Writing, and Literacy Research, edited by Maureen Daly Goggin and Peter N. Goggin, Utah State P, 2018, pp. 205-218.

de Certeau, Michel. The Practice of Everyday Life, translated by Steven Rendall. 2nd ed., U of California P, 2011.

Derrida, Jacques. On the Name. Translated by David Wood, John P. Leavey Jr. and Ian McLeod. Stanford UP, 1995.

Dickinson, Greg, et al. “Spaces of Remembering and Forgetting: The Reverent Eye/I at the Plains Indian Museum.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, vol. 3, no. 1, 2006, pp. 27-47.

Dobrin, Sidney. Ecology, Writing Theory, and New Media. Routledge, 2015.

Driskill, Qwo-Li. “Doubleweaving Two Spirit Critiques: Building Alliances Between Native and Queer Studies.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, vol. 16, no. 1-2, 2010, pp. 69-92.

Edbauer Rice, Jenny. “Unframing Models of Public Distribution: From Rhetorical Situation to Rhetorical Ecologies.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 35, no. 4, June 2009, pp. 5-24.

Edwards, Dustin. “Digital Rhetoric on a Damaged Planet: Storying Digital Damage as Inventive Response to the Anthropocene.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 39, no. 1, Jan. 2020, pp. 59-72.

Gantt, Sandra. Personal interview. 15 Jan. 2018.

“Ghost Walk in Pendleton.” Discover South Carolina, http://discoversouthcarolina.com/products/28931.

Gries, Laurie. Still Life with Rhetoric: A New Materialist Approach to Visual Rhetorics. UP of Colorado, 2015.

Haas, Angela M. “Wampum as Hypertext: An American Indian Intellectual Tradition of Multimedia Theory and Practice.” Studies in American Indian Literatures, vol. 19, no. 4, 2007, pp. 77-100.

Hassan, Terence. Personal interview. 19 Feb. 2018.

Hawk, Byron. A Counter-History of Composition: Toward Methodologies of Complexity. U of Pittsburgh P, 2007.

Heidegger, Martin. “Building Dwelling Thinking.” Poetry, Language, Thought, translated by Albert Hofstadter. Harper Colophon Books, 1971.

Hurley, Elise Verzosa. “Spatial Orientations: Cultivating Critical Spatial Perspectives in Technical Communication Pedagogy.” Key Theoretical Frameworks: Teaching Technical Communication in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Angela M. Haas and Michelle F. Eble, Utah State UP, 2018, pp. 94-113.

Jackson, Peter, editor. Race and Racism: Essays in Social Geography. Routledge, 1987.

Jackson, Rachel, and Dorothy Whitehorse DeLaune. “Decolonizing Community Writing with Community Listening: Story, Transrhetorical Resistance, and Indigenous Cultural Literary Activism.” Community Literacy Journal, vol. 13, no. 1, Fall 2018, pp. 37-54.

Jones, Natasha, and Rebecca Walton. “Narratives to Foster Critical Thinking About Diversity and Social Justice.” Key Theoretical Frameworks: Teaching Technical Communication in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Angela M. Haas and Michelle F. Eble, Utah State UP, 2018, pp. 241-267.

Jones, Natasha, et al. “Disrupting the Past to Disrupt the Future: An Antenarrative of Technical Communication.” Technical Communication Quarterly, vol. 25, no. 4, 2016, pp. 211–229.

King, Lisa, et al. Survivance, Sovereignty, and Story: Teaching American Indian Rhetorics. Utah State UP, 2015.

King, Thomas. The Truth About Stories: A Native Narrative. U of Minnesota P, 2005.

Kobayashi, Audrey, and Linda Peake. “Racism Out of Place: Thoughts on Whiteness and an Antiracist Geography in a New Millennium.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, vol. 90, 2000, pp. 392-403.

Lefebvre, Henri. The Production of Space. Wiley-Blackwell, 1992.

Loften, Adam, and Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee. “Counter Mapping.” Emergence Magazine. https://emergencemagazine.org/story/counter-mapping/.

Massey, Doreen. For Space. Sage Publications, 2005.

McKittrick, Katherine. Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle. U of Minnesota P, 2006.

---. “On Plantations, Prisons, and a Black Sense of Place.” Social & Cultural Geography, vol. 12, no. 8, 2011, pp. 947-63.

Nelson, Lise. “Racialized Landscapes: Whiteness and the Struggle Over Farmworker Housing in Woodburn, Oregon.” Cultural Geographies, vol. 15, 2008, pp. 41-62.

O’Brien, April. “The Ghosts of Pendleton.” Journal for Cultural and Religious Theory, vol. 16, no. 1, 2016, http://www.jcrt.org/archives/16.1/Obrien.pdf.

O’Brien, April, and James Chase Sanchez. “Racial Countermemory: Tourism, Spatial Design, and Hegemonic Remembering.” The Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics, forthcoming.

Plato. Timaeus. Penguin Classics, 2008.

Powell, Malea. “Learning (Teaching) to Teach (Learn).” Relations, Locations, Positions: Composition Theory for Writing Teachers, edited by Peter Vandenberg et al. NCTE Press, 2006, pp. 571-580.

Powell, Malea et al. “Our Story Begins Here: Constellating Cultural Rhetorics Practices.” enculturation, vol. 18, 25 Oct. 2014, http://enculturation.net/our-story-begins-here.

Quigley, Stephen. “Welcome to the Letters of Anna Calhoun Clemson.” Kairos, vol. 22, No. 2, 2018, http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/22.2/disputatio/quigley/index.html.

Reynolds, Nedra. Geographies of Writing: Inhabiting Places and Encountering Difference. Southern Illinois UP, 2004.

Rickert, Thomas. Ambient Rhetoric: The Attunements of Rhetorical Being. U of Pittsburgh P, 2013.

---. “Toward the Chōra: Kristeva, Derrida, and Ulmer on Emplaced Invention.” Philosophy and Rhetoric, vol. 40, no. 3, 2007, pp 251-273.

Riley-Mukavetz, Andrea. “Theory Begins with a Story, Too”: Listening to the Lived Experiences of American Indian Women. 2012. Michigan State University, PhD dissertation, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

Sackey, Donnie Johnson. “An Environmental Justice Paradigm for Technical Communication.” Key Theoretical Frameworks: Teaching Technical Communication in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Angela M. Haas and Michelle F. Eble, Utah State UP, 2018, pp. 138-160.

Sanchez, James Chase. “Recirculating Our Racism: Public Memory, Folklore, and Place in East Texas.” Inventing Place: Writing Lone Star Rhetorics, edited by Casey Boyle and Jenny Rice, Southern Illinois UP, 2018, pp. 75-87.

Sibley, David. Geographies of Exclusion. Routledge, 1995.

Soja, Edward. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places. Blackwell, 1996.

Tell, Dave. Remembering Emmett Till. U of Chicago P, 2019.

Ulmer, Gregory. Heuretics: The Logic of Invention. The Johns Hopkins UP, 1994.

Walters, E.V. Placeways: A Thory of the Human Environment. U of North Carolina P, 1988.

Walton, Rebecca, et al. Technical Communication After the Social Justice Turn. Routledge, 2019.

Wilson, Shawn. Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Fernwood Publishing, 2008.