Crystal VanKooten, Oakland University

(Published November 22, 2016)

In 1992, Gesa Kirsch characterized research in the field of rhetoric and composition using the phrase methodological pluralism: writing researchers were drawing from a variety of research traditions and fields, including literary studies, history, education, linguistics, psychology, sociology, and anthropology (“Pluralism” 247). Debates about practices, epistemology, and ideology related to the various methodologies for inquiry into writing and its processes were then just beginning, yet similar discussions continue today, and even more so as the study of rhetorical practice shifts to focus on texts composed in and through the digital medium. Just as it was in 1992, current approaches to methodology shape how we might observe and analyze texts, acts of composition, and learning—our methods affect what new knowledge we are able to make. Methodological considerations take on particular significance for the growing group of scholars who study, practice, and teach digital rhetoric. Digital rhetoricians examine, create, and theorize digital texts and the myriad practices surrounding them, a process that, in its complexity, necessitates developing new and hybrid methodologies.

Literacy researchers and videographers Bump Halbritter and Julie Lindquist describe methodology as “a way of imagining inquiries into particular questions” (174); methodology is the big picture of how research is theorized and framed, and it encompasses the systems that inform particular research practices, which are the research methods themselves. Those methods, the particular practices, for Halbritter and Lindquist, “are examples of local processes; methodologies are examples of global operations” (174). Digital humanist Tom Scheinfeldt has talked about the “seasonal shifting between methodological and theoretical work” in fields as they emerge over time (57). Digital Humanities (DH) scholars, he points out, “traffic less in new theories than in new methods,” playing with digital materials, tools, techniques, and modes (58). Is digital rhetoric, then, like DH, in a similar place of methodological experimentation? What are the global operations, the methodologies, of digital rhetoric? Subsequently, what are the local processes that those studying digital rhetoric are using to enact methodologies? And when we begin to take stock of the methodologies and methods of digital rhetoric, how might a consideration of these operations and processes help us to do the work of defining digital rhetoric as an emerging field?

In this article, I use a case study to work toward answers, examining the research methodologies and methods of the thirty presenters at the Indiana Digital Rhetoric Symposium (IDRS), held at Indiana University in April 2015. My analysis of their work reveals that the methodologies and methods of digital rhetoric are rooted most firmly in rhetorical theory and the analysis of written and digital texts, but these methods are beginning to expand to include more experimental, interdisciplinary approaches to research that include digital composition, empirical observation, and self-definition.

Research Methods

I started my inquiry into the methodologies and methods of digital rhetoric by mapping out several research questions:

1. What research methodologies (global operations) and methods (local processes) are in use by digital rhetoricians?

2. How do research methodologies and methods define the work of digital rhetoric?

3. Are researchers in digital rhetoric drawing on methodologies from other fields?

4. What might distinguish the methods of digital rhetoricians from other methods in the digital humanities, rhetoric and composition, or other fields?

To address these questions, I treated the work of the thirty speakers at the IDRS as a case study, as one site that can speak to how we are defining and enacting methods and methodologies for digital rhetoric.

First, I examined the content of the IDRS presentations as represented in the IDRS abstracts, asking questions about what methods and methodologies I could observe being used. I supplemented information from the abstracts with other descriptions of digital rhetoric scholarship and research found via a web search and a library database search. To find this additional information, I googled the names of the speakers on the IDRS program and read through the results, which included professional and school-based websites, CVs, academia.edu profiles, and Facebook and Twitter profiles. Through the library, I looked up the presenters’ books and articles and scanned the abstracts.

After examining and taking notes on this data set, which included the IDRS abstracts, presenters’ web materials, and books and articles authored by IDRS participants, I wrote up a phrase for each presenter that described his or her methodological approach to research (I used multiple phrases for the work of some IDRS presenters that fell into multiple categories), and I grouped each person’s work with other similar work. Online, some IDRS participants talked directly about a methodological orientation for their research, and others did not. When needed, I intuited methodological stance(s) based on what I saw and read. Once presenters were grouped based on over-arching methodology, I put together lists of particular methods and modes of delivery used for each group based on what I could observe in the work. I also compiled a list of academic fields with which each presenter was affiliated. Four over-arching categories of methodological approaches emerged from this analysis: 1) hermeneutics, 2) digital composition, 3) empirical observation of human experience, and 4) self-definition. I explore each of these methodologies, along with their related methods and modes of delivery, in detail below.

Findings

Hermeneutics

The first methodological approach to digital rhetoric can be labeled hermeneutics: the science and theory of textual interpretation, often related to biblical, literary, or philosophical texts. The work of twenty-three out of thirty IDRS presenters fits within this category, and the methods employed within this methodology include analysis of written theoretical texts (notably rhetorical theory) along with analysis of digital or material texts, all used to theorize aspects of digital-rhetorical experience. These twenty-three scholars weave together analysis of written and digital texts to theorize about how digital texts communicate and about the practices that users and authors participate in when they compose or consume digital texts, and they deliver their work via book and article manuscripts and oral conference presentations.

| Scholar / Researcher | Analysis of Written Texts | Analysis of Digital or Material Texts |

|---|---|---|

|

Caddie Alford |

rhetorical theory |

Twitter hashtags |

|

Kristin Arola |

composition theory, American Indian philosophy |

Facebook/Myspace, the digital asset

|

|

Sarah Arroyo |

rhetorical theory |

online video |

|

Estee Beck |

rhetorical theory |

websites, algorithms |

|

Casey Boyle |

philosophy |

networked events, digital products |

|

Kevin Brock and Ashley R. Kelly |

rhetorical theory and genre studies |

Drupal modules and code |

|

Collin G. Brooke |

rhetorical theory |

objects that go viral |

|

James J. Brown Jr. |

rhetorical theory |

Wikipedia |

|

E. Cram, Melanie Loehwing, John L. Lucaites |

digital visual rhetoric |

photographs

|

|

Matthew Demers |

rhetorical theory, cyber-history |

architectural works of Le Corbusier |

|

Bill Hart-Davidson |

rhetorical theory |

human-coded text corpus of scientific discourse and online discussions |

|

Byron Hawk |

rhetorical theory |

sound artist Stanley’s work |

|

Steve Holmes |

rhetorical theory |

mobile and gamified applications |

|

David Rieder |

rhetorical theory |

sensor data visualizations |

|

Jeff Rice |

rhetorical theory |

|

|

Thomas Rickert |

rhetorical theory |

|

|

Nathaniel Rivers |

actor-network theory |

Geocaching |

|

Annette Vee |

law writing |

patent law, Creative commons, Common Terms |

|

Anne Wysocki |

philosophy |

interactive software that utilizes touch |

|

Kathleen Blake Yancey |

rhetorical theory |

Hill’s manual |

As Table 1 indicates, those using a hermeneutic approach to digital rhetoric are drawing most often from written rhetorical theory, but also at times from composition theory, philosophy, social theory, and law writing to articulate their own theories. The digital and material sites of analysis, in contrast, include a wide range: these scholars are looking closely at social networking sites and activities (Facebook, Twitter, and other online discussion forums); at webpages, algorithms, and the code behind webpages; at mobile, interactive, and GPS software, applications, and devices; at photography; at works of architecture and sound art, and even, in a few cases, at historical texts. The sites of analysis for hermeneutic inquiry are diverse, but they are all linked to how digital texts communicate to authors and audiences—through the web, through mobile devices, and through images, structures, and sounds.

Digital Composition

The second methodological approach that came to the fore in this case study is digital composition. Digital composition as methodology for inquiry involves various methods, some of which begin to become visible through the work of seven IDRS presenters. Through the use of non-discursive, alternate forms of analysis and synthesis, these methods go beyond using digital composition only for delivery. Methods include, for example, the combination of modes of expression such as words, images, and sounds as a form of analysis, as well as the creation, collection, juxtaposition, and repurposing of media assets and objects as synthesis. Additionally, these methods are enacted in digitally-mediated spaces: on video and audio, in digital books, through repurposed digital objects like the Gameboy camera, or through digital sculpture. As Table 2 indicates, there are seven examples of IDRS scholars and researchers that use digital composition as a methodology for inquiry. Notably, five out of seven use a form of video, perhaps in part because hardware and software for video composition have become more accessible and usable in the past decade—a video author no longer needs a computer lab or specialized equipment to experiment, analyze, and compose with video.

| Scholar / Researcher | Methods | Sites of Analysis/Composition and Delivery |

|---|---|---|

|

Angela Aguayo |

combination of modes of expression; juxtaposition |

documentary video, oral history |

|

Kristin Arola |

combination of modes of expression; juxtaposition |

video, digital book |

|

Sarah Arroyo |

combination of modes of expression; juxtaposition |

video |

|

James J. Brown Jr. |

collection of media objects and assets; repurposing |

cameras and digital objects |

|

David Rieder |

combination of modes of expression; juxtaposition, interaction |

GPS-based sculpture, digital interactive community project |

|

Nathaniel Rivers |

combination of modes of expression; juxtaposition |

video and audio |

|

Crystal VanKooten |

combination of modes of expression; juxtaposition |

video |

It is noticeable that only seven of thirty IDRS participants are using digital composition itself as a methodology in highly visible ways. In 2004, computers and writing scholar Cheryl Ball stated:

composition and new media scholars write about how readers can make meaning from images, typefaces, videos, animations, and sounds, but most scholars don’t compose with these media. It is evident from the scholarship available that compositionists are interested in new media. Yet, they do not seem to value creating new media texts for scholarly publications to explore the multimodal capabilities of new technologies. (407)

The multimodal capabilities that Ball references include the ability of digital composition to function as methodology, as a site for various local processes and methods of inquiry, including those listed above and more. However, based on the findings of this case study, Ball could still be talking to many digital rhetoricians in 2015: relatively few of today’s scholars in digital rhetoric are doing the work of digital composition and exploring its methodological potential. Composing with and using digital media for analysis as academics, of course, is complex. There are tenure requirements. There are the kinds of texts that journals solicit and publish. There is the learning curve for new or unfamiliar technologies and the extended time required to use many digital tools. There can be a bias against multimodal, digital scholarship and in favor of written scholarship. Even so, along with Ball, I continue to call digital rhetoricians to do the work of enacting scholarship through digital composition, to use composing with multiple and digital modes of expression as a methodology for inquiry into how digital texts communicate. Digital composition is a way of making new knowledge that digital rhetoric might tap into with more regularity.

Empirical Observation of Human Experience with Digital Texts and Digital Composition

Seven IDRS presenters are doing empirical, observational work of others’ experiences with digital texts and digital composition. As shown in Table 3, the various empirical methods they use include direct observation and analysis of community or classroom experiences, interviews, observation and aggregation of online discussions through corpus analysis, and ethnography. While the line between hermeneutics and empirical observation can sometimes blur, what sets an empirical approach apart from other methodologies is a focus on observing or documenting human experience with digital texts. Where others seek evidence in written theoretical texts and digital objects, empirical researchers do so through direct observation of others, at times using interviews, pedagogical documents, or compilations of records of online interaction.

| Scholar / Researcher | Methods | Sites of Observation/Analysis |

|---|---|---|

|

Matthew Demers |

direct observation |

school of architecture class’s experience |

|

Doug Eyman |

analysis of pedagogical documents, case studies |

course descriptions and syllabi, three teachers of digital rhetoric and their courses |

|

Bill Hart-Davidson |

observation and aggregation of online discussion through corpus analysis |

scientific discourse and online discussions |

|

Crystal VanKooten |

direct observation, interviews |

writing classrooms, students and teachers |

|

Jennifer Warfel Juszkiewicz & Joe Warfel |

direct observation |

discourse of the mathematical programming community |

|

Jon Wargo

|

ethnography, discourse analysis |

LGBT youth’s moments of media making on SnapChat and Tumblr |

The use of empirical methods for digital rhetoric parallels the turn to methodological diversification that has been occurring in rhetoric and composition more broadly over the past several decades. Kirsch tells us that currently in writing studies, “no longer do scholars apologize for using, adapting, or borrowing methods that originated in the social sciences,” but instead, writing researchers offer critiques, insights, reflections, explanations, and arguments for new, hybrid approaches to research (Foreword xv). Empirical research based on systematic observation has thus become more and more common in rhetoric and composition, and more and more rigorous, and this shift is beginning to show itself in digital rhetoric, as well.

In 1996, computers and writing scholar Scott DeWitt pointed out the dearth of empirical research that addressed what was then called “hypertext” and composing practices. DeWitt wrote that within computers and composition studies, “we see only a sparse tendency towards carefully designed empirical research studies—where research questions and research methodologies are explicitly stated and collected data analyzed, as well as where student experiences are revealed, and pedagogical agendas exposed” (70). Like Ball, DeWitt could still be making these same comments today about digital rhetoricians, nineteen years later, as this case study reveals. While some of the work in digital rhetoric parallels the turn to empirical research within rhetoric and composition, there is a need for more carefully designed empirical studies that focus on digital composition and rhetorical expression in digital spaces, on the uses of technologies inside and outside of schools, and on the teaching of digital rhetoric so that theories and practices can move beyond the anecdotal. More empirical observation would allow digital rhetoricians to look systematically across multiple experiences with digital texts and to be more clear about why and how they choose sites and methods of inquiry.

Self-Definition

The final category that came to the fore in this case study is the methodology of doing self-definitional work, of defining what digital rhetoric is and how digital rhetoric is enacted. Two IDRS presenters, Doug Eyman and Elizabeth Losh, are doing this work most directly in ways that were evident in the IDRS abstracts and other published work. In Digital Rhetoric: Theory, Method, Practice, for example, Eyman turns to definitions through a discussion of rhetorical and media theory and through examining pedagogical materials including course descriptions and syllabi. Losh, in Virtualpolitik, explores four areas of the study of digital rhetoric: 1) the conventions of new digital genres, 2) public rhetoric, 3) the emerging discipline of digital rhetoric, and 4) mathematical theories of communication from information science (47). At IDRS, Losh then extended this work through analysis of the complex texts of online transnational remixers who compose on Twitter, YouTube, and within online games. Both Eyman and Losh invite digital rhetoricians to extend our inquiries—to look to the pedagogical, to public discourse, to information science, and to online spaces to extend definitions of what digital rhetoric is and how it is enacted.

Digital Rhetoric as an Emerging Field

The findings thus far provide one answer to the first research question of what methodologies and methods digital rhetoricians use. To summarize, most of the scholars in the case study are using a hermeneutic approach to digital rhetoric, discussing how digital texts communicate as they draw on rhetorical and other written theories and on the analysis of digital texts and their uses in various spaces. Some within the sample are exploring multimodal forms of analysis and synthesis through composing digital texts, and others are using qualitative and empirical methods to begin to more systematically inquire into how humans use digital technologies to communicate and persuade. A few are defining digital rhetoric as it emerges as a field stemming from and related to several other fields and discourses.

As illustrated in Table 4, most of the IDRS presenters use rhetorical theory in their research – twenty do so directly. Even so, there are voices from other fields in the mix: from composition, philosophy, communication, programming, architecture, and law, for example. In this way, perhaps digital rhetoric may be headed in a similar direction as the Digital Humanities. Matthew Kirschenbaum has explained that DH projects are interdisciplinary and collaborative at their core, they “depend on networks of people” (6) that aren’t necessarily from the same discipline. The work of IDRS presenters shows some movement in such a collaborative, cross-disciplinary direction: some of the work is already collaborative; some of the work relies on knowledge not only from rhetoric but from other fields and disciplines.

| Academic Field | Number of IDRS Presenters |

|---|---|

|

Rhetoric Alford, Arroyo, Beck, Boyle, Brock, Brooke, Brown, Demers, Eyman, Hart-Davidson, Hawk, Holmes, Kelly, Losh, Rieder, Rice, Rickert, Rivers, Vee, Yancey |

20 |

|

Composition / Rhetorical Genre Studies Arola, Brock, Kelly, VanKooten |

4 |

|

Philosophy Arola, Boyle, Wysocki |

3 |

|

Communication (Visual Rhetoric) Cram, Loehwing, Lucaites |

3 |

|

Mathematical Programming/Modeling Warfel Juszkiewicz and Warfel |

2 |

|

Architecture Demers |

1 |

|

Documentary Film / Interdisciplinary Aguayo |

1 |

|

Education / Literacy Studies Wargo |

1 |

|

Information Science Losh |

1 |

|

Law Vee |

1 |

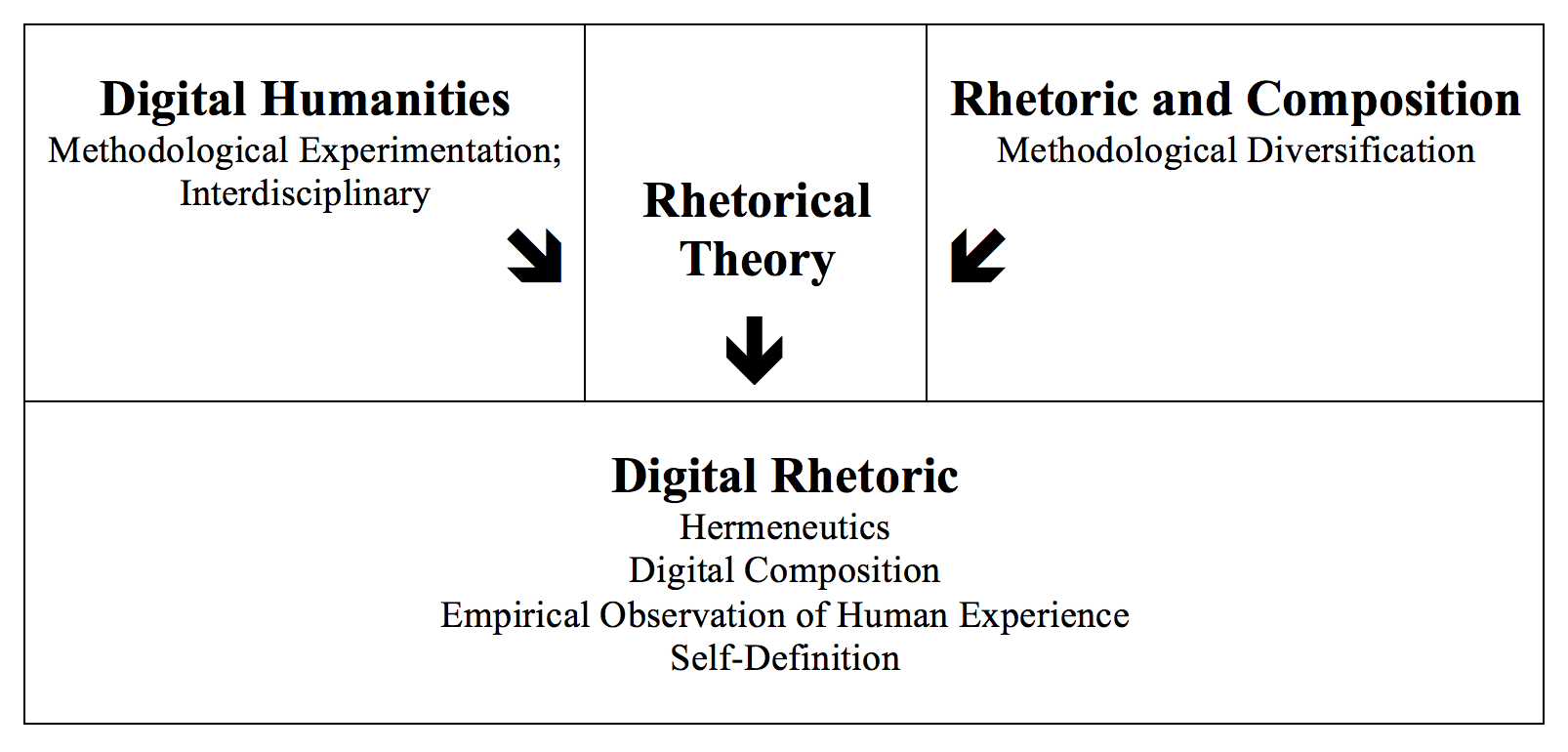

Below, Figure 1 represents how this case study has helped me to think about digital rhetoric’s relationship to sister fields and discourses as it begins to emerge as a field of study of its own. The work of digital rhetoric shows some movement toward a “methodological experimentation with digital tools” phase, like that which is occurring in the Digital Humanities; digital rhetoric also includes some interdisciplinary work as is more common in DH. From rhetoric and composition, digital rhetoricians bring a recently developed openness to new and diverse research methods. But what makes digital rhetoric unique is a strong foundation in rhetorical theory that speaks to how and why authors might compose and experiment with tools or design new or hybrid methods for inquiry.

Figure 1: Digital rhetoric’s relationship to sister fields and discourses

Limitations

Of course, drawing conclusions about the status of digital rhetoric as an emerging field based on one case study has limitations, one of which is the sites for data collection. I drew from IDRS participants’ published or public scholarship, examining IDRS presentations, peer-reviewed journal articles and books, and online self-published materials. Excluded from the data set is work that is in progress, unpublished, or that occurs within the classroom. For some, digital composition, experimentation with digital tools, and empirical observation might occur in alternate, less publically visible spaces. A second limitation may be the terminologies in use to solicit, define, and classify the work of digital rhetoric. Some scholars, for example, explicitly call themselves digital rhetoricians, and many of these individuals responded to the IDRS call for papers. Others within communications, rhetoric and composition, information science, or related fields might be participating in the kind of work that is labeled digital rhetoric here, but instead using shifted labels and terminologies such as computers and writing, digital composition, digital humanities, digital media, multimodal composition, new literacies, new media, and more. The specific terminologies in use, then, may have limited the data set in some ways.

Conclusion

Using the work of the presenters at IDRS as a case study reveals that the methodologies and methods for digital rhetoric—both the global operations and the local processes—are in flux; they are as yet emerging. Many digital rhetoricians take a hermeneutic approach to research through analysis of written theory and digital examples, and this aligns us with more traditional methodologies within the humanities and within English departments. Some digital rhetoricians are beginning to use digital composition as a methodology, to design new methods for observation and data collection in digital spaces, and to draw on fields outside of rhetoric and writing that have built knowledge about the digital. This movement mirrors the current methodological experimentation phase of the Digital Humanities, which looks across disciplinary boundaries more readily. These new methodological movements for digital rhetoric are located in somewhat unfamiliar spaces, spaces populated by colleagues from the learning and social sciences, from cinema studies and design, and from information science. Even amidst such uncertainty, however, it is exciting to see where digital rhetoric might go from here, to see who digital rhetoricians might work with and what they will compose, and to see the new and assembled methodologies and methods that they might design to learn more about how digital texts are composed and experienced in the world.

Ball, Cheryl E. “Show, Not Tell: The Value of New Media Scholarship.” Computers and Composition, vol. 21, no. 4, Jan. 2004, pp. 403–425.

Dewitt, Scott Lloyd. “The Current Nature of Hypertext Research in Computers and Composition Studies: An Historical Perspective.” Computers and Composition, vol. 13, no. 1, 1996, pp. 69–84.

Eyman, Douglas. Digital Rhetoric: Theory, Method, Practice. University of Michigan Press, 2015. muse.jhu.edu, https://muse.jhu.edu/book/40755.

Halbritter, Bump, and Julie Lindquist. “Time, Lives, and Videotape: Operationalizing Discovery in Scenes of Literacy Sponsorship.” College English, vol. 75, no. 2, Nov. 2012, pp. 171–198.

Kirsch, Gesa. “Foreword: New Methodological Challenges to Writing Studies Researchers.” Writing Studies Research in Practice: Methods and Methodologies, edited by Lee Nickoson and Mary P. Sheridan, Southern Illinois UP, 2012, pp. xi–xvi.

---. “Methodological Pluralism: Epistemological Issues.” Methods and Methodology in Composition Research, edited by Patricia A. Sullivan and Gesa Kirsch, Southern Illinois UP, 1992, pp. 247–269.

Kirschenbaum, Matthew. “What Is Digital Humanities and What’s It Doing in English Departments?” ADE Bulletin, Sept. 2015, pp. 1–7.

Losh, Elizabeth M. Virtualpolitik: an Electronic History of Government Media-Making in a Time of War, Scandal, Disaster, Miscommunication, and Mistakes. MIT P, 2009.

Scheinfeldt, Tom. “Theory, Method, and Digital Humanities.” Hacking the Academy: New Approaches to Scholarship and Teaching from Digital Humanities, edited by Dan Cohen and Tom Scheinfeldt, U of Michigan P, 2013, pp. 55–9. muse.jhu.edu, http://muse.jhu.edu/chapter/833159.