Alexandra Hidalgo, Purdue University

Enculturation: http://www.enculturation.net/national-identity

(Published: June 18, 2012)

THE SHRINKING B

Figure 1: Toy store advertisement

Growing up in Caracas, Venezuela, in the 1980s, I knew that the greatest accomplishment for any woman would be winning the Miss Venezuela beauty contest. I didn’t dare dream I would ever compete, however. My legs were too thick and my “potato nose,” as my cousin disdainfully called it, was bound to outrage the judges. By the time I became a teenager, the list of anatomical crimes committed by my body could cover a few pages of rampant (and I’d later learn nonsensical) dissatisfaction. However, my breasts never made it on the list. Sure, as a B-cup I didn’t turn heads with my cleavage, but it didn’t matter. So few of my classmates had any cleavage to speak of. B-cups were the norm in my school, and we had other things to obsess over, like split ends and slightly protruding bellies. Things that could actually be altered.

In 1993, when I was 16 years old, I moved to Dayton, Ohio, and have since returned home every other year to find that my breasts are shrinking. It started slowly, but about 12 years ago it exploded. Cs and Ds and other letters I’d never heard of in relation to bras were parading up and down the streets, making my Bs look incongruously small. The unalterable was being altered everywhere I looked. One by one my dearest friends chose to have breast implant surgery when none of my American friends would dream of it.

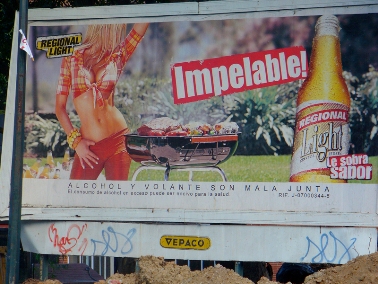

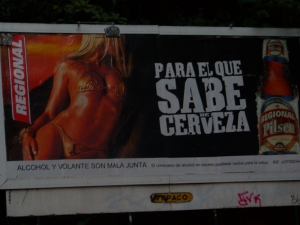

Figure 2: Beer advertisement

Something happened in my native country, and living abroad I failed to both be part of it and understand it, which is why when I purchased my first video camera, I booked a ticket home and made Perfect: A Conversation with the Venezuelan Middle Class About Female Beauty and Breast Implants, a 25-minute documentary shot in English and Spanish1. In this essay, I will use the 13 participants’ responses to analyze the rhetorical strategies they use to explain their own and Venezuela’s fascination with breast implants. I will show clips from the film to provide readers/viewers with a more intimate look at the participants’ particular ways of speaking and the tone, often playful, with which they address the issue.

I draw from material rhetoric to frame the participants’ responses since, as this essay will show, many Venezuelans’ reasons for undergoing breast implant surgery—a material transformation of women’s bodies—are not medical but rather the result of the country’s cultural rhetoric about the beauty, value, and goodness of women. Krista Ratcliffe asserts that “materiality may be introduced into rhetorical studies not just in terms of the subjects/objects studied but also in terms of their associated discourses” (618). In this essay, I will analyze the ways in which the documentary participants present and mold Venezuela’s cultural rhetoric about breast implants in order to navigate the contradictions in their relationship with the surgery. The participants realize and are bothered by the fact that Venezuelan culture has caused them to either want (for the women) or enjoy (for the women and men) breast implants, and yet, most of them still see the surgery as ultimately positive for themselves and for the country2.

Figure 3: Beer advertisement

In their attempt to make sense of their contradictory feelings and opinions about breast implants, the participants use five rhetorical strategies. The first four—arguments that breast implants are the norm, that they enhance self-esteem, that large breasts constitute the only source of female beauty and that they provide equilibrium—support the findings of my fellow feminist scholars3. The last strategy—the argument that they are part of our national identity—diverges from previous scholarship on the subject. Venezuela’s culture has a number of correlations with breast implants in America, yet it also provides fresh and unconventional ways in which to understand women and men’s relationships to plastic surgery.

Studying people’s relationships to plastic surgery can help extend our understanding of material rhetoric as it is mapped onto female bodies. As Sharon Crowley explains, “The scholarly focus on bodies and material practices owes much to the second-wave American feminists who launched a thoroughgoing critique of received attitudes about sex, gender and the body” (357-358). In spite of its origins in feminism, material rhetoric lends itself to the study of “women who are not feminist prototypes, women whose texts may even be implicated in patterns of hierarchy and domination” (Tolar Collins 550). Non-feminist women—and I will argue men—have much to offer feminism, providing a better understanding of the forces keeping women from reaching equality and helping scholars and feminists connect with those who stand outside feminism and may not approve of it (Tolar Collins 550). Although most of the women and men in this documentary do not seem to hold feminist ideals, I will show that their opinions about breast implants can help us find ways to argue for alternatives to plastic surgery both in and outside Venezuela.

Figure 4: Women walking

While I will support my claims with the findings of other feminist scholars, this essay focuses on Venezuelans’ perceptions of breast implants rather than on facts about plastic surgery in my country. As Naomi Wolf explains, it is hard to obtain trustworthy statistics about plastic surgery (237). According to Jesus Pereira, secretary of the Venezuelan Society of Plastic Surgeons, about 30 percent of women between 18-40 have undergone breast implant surgery with a yearly total of 30,000 to 40,000 women undergoing the procedure (Romero). I am not sure that these numbers are reliable since they come from the plastic surgery industry and are not backed up by any government or independent sources. None of the documentary participants were aware of these or any statistics on the issue when interviewed. Instead, they rely on the experiences of those around them, as well as their own, and most of the women they know have already had the surgery or are considering having it in the near future. I would also like to point out that “most of the women they know” is a key qualifier here, since these women, like the participants themselves, belong to the middle class.

Figure 5: Waiter amused by beer advertisement

I chose to only interview members of the middle class (to which I belong) because the breast implant phenomenon has mainly affected the middle class and the rich. The main reason for this is that even if working-class and poor women would like to have breast implants (and further study would be needed to determine whether that is in fact the case), the vast majority of them cannot afford them. In spite of being the fifth largest oil-producing country in the world, Venezuela is crippled by paralyzing class disparities, which make breast implant surgery prohibitive to the approximately 80 percent of our population that constitutes the working class and the poor. Thus, the notion that most Venezuelan women have breast implants is in fact illusive, since the use of implants tends to be limited to the middle class and the rich, who comprise a small percentage of the population. However, the middle class and the rich are in control of most of the Venezuelan media, so that the aesthetic on television, advertising, and music tends to be that of the middle class’s embracement of breast implants4.

While there is no class diversity in the documentary participants, I felt that members of both genders needed to be interviewed. Kathryn Pauly Morgan argues that “[i]t is only once we have listened to the voices of women who have elected to undergo cosmetic surgery that we can try to assess the extent to which the conditions for genuine choice have been met” (33). Although I agree with her that we need to talk to women who have had surgery if we are going to understand the forces behind different countries’ embracing of cosmetic surgical procedures, I would argue that men’s perspectives are also vital. After all, as Brenda Weber explains in her study on television makeovers, most surgical and non-surgical transformations attempt to make female subjects attractive to men (and male subjects attractive to women). As I will show below, in concordance with Weber’s analysis, Perfect’s participants think of their implants in terms of pleasing the male gaze. It is also important to note that the rhetorical strategies used by female participants are similar to those used by male participants when trying to unravel their conflicted relationship to breast implants.

THE NORM

Figure 6: People entering a mall

When I moved to Dayton at 16, I was shocked when my first American friend, Julie, told me she was dying her hair that weekend and asked if I wanted to come along and dye mine too. I’d seen a few green-haired students at Centerville High School but they were outcasts. Julie was not one of the “weird” kids and here she was confessing to dying her hair. I’d had a friend back in Caracas who also dyed her hair. “Marissa” (even today I cannot betray her by revealing her real name) was one of the few blondes in our class. Light-eyed and golden-haired, her coloring embodied the dream so many of us aspired to in vain. It took Marissa years to confess her secret to me. Her eyes were real, but although her hair had been golden as a girl, it had begun to darken as she grew older. In desperation she’d taken to dying it. The shamefully confessed secret hung heavy with me. Never to be revealed until I write this almost 20 years later.

Dying one’s hair constituted cheating. A little bit of makeup might be tolerated on the more popular girls, but the rest of a girl’s beauty had to be natural, authentic. It wasn’t until my Ph.D. that I ran into Naomi Wolf’s The Beauty Myth. Wolf explains that “‘[b]eauty’ is not universal or changeless, though the West pretends that all ideals of female beauty stem from one Platonic Ideal Woman; the Maori admire a fat vulva, and the Padung, droopy breasts. Nor is ‘beauty’ a function of evolution: Its ideals change at a pace far more rapid than that of the evolution of the species” (12). Of course Wolf is right, but it took weeks for me to digest the idea. Even though I can now see that beauty is a constrictive social construct, it was hard to let go of my upbringing.

The reason why Marissa’s hair dying was so shameful back then is that not only did we believe that there was an ideal of (mostly Eurocentric) beauty, but any traces of that ideal found in our faces and bodies were a reflection of a deeper inner goodness, an indication of the quality of our hearts and souls—as I gave up the concept of universal beauty, I also had to give up whatever goodness I’d been assumed to possess because of my own “beauty.” As scholars have pointed out, the connection of beauty with goodness is fed early to Western children through fairy tales in which the heroes are beautiful and the villains ugly, with blondness representing youth and innocence (Ostry 94). Marissa’s dyed golden hair was not simply a lie about her appearance. It was a lie about her inner identity, about her value as a human being.

How did we go from Marissa’s torment to here?

Download video: Ogg format | MP4 format

The videos included in this essay are excerpts of a full-length documentary. The entire film is available at: http://alexandrahidalgo.com/perfect.php

Marlén, one of Perfect’s participants, says that when she had her breast implants done in 1981, they were “still a taboo,” so she kept them a secret. María Fernanda adds, “I do recall, for example, when I was in college, one friend getting breast implants and it was like ‘oh, my God,’ everybody was so shocked. I even got jealous friends that said, ‘I’m going to let everybody know because this is outrageous’ and ‘how dare she’ and stuff like that. And now in my office, there are basically a few of us who don’t have breast implants.” Her coworker, Edith, concurs, “At first it wasn’t important, it didn’t matter whether or not you had breast implants. Now I think it’s more normal to have them than not. And those who don’t have them and are teenagers or twenty-year-olds are going to get them. You think, ‘I want a car, I want a job and I want boobs.’” Edith, like many of her fellow participants, refers to the implants as boobs, not implants—the common term for the procedure is “having one’s boobs done,” as if the breasts women are born with do not count as “real” breasts anymore.

Edith’s sense that it is “normal” for women to have breast implants coincides with the findings of Patricia Gagné and Deanna McGaughey, who conducted a study on 15 women who had undergone various cosmetic breast surgeries and write that “[a]ll of the women we interviewed talked about cosmetic surgery as a normal procedure that nearly all women would choose if they had the means to do so” (201). If breast surgery statistics were easily available in Venezuela and the United States (where Gagné and McGaughey’s study takes place), many women would see that in spite of their beliefs to the contrary, the majority of women do not have or probably even want breast implants. However, since cosmetic surgery statistics are elusive, depending on what groups we move in it may indeed seem that everyone is opting for surgery.

Figure 7: Marlén

The belief that women everywhere are having plastic surgery begins to unravel the change that both María Fernanda and Edith pinpoint, but it is not enough. What else caused Venezuelan women to go from worrying about “lies” like the one told by Marissa’s hair to wishing for breast implants as we would for a car and a job? In her widely studied essay on postfeminism, Angela McRobbie explains that “individuals must now choose the kind of life they want to live. Girls must have a plan” (35). Tasker and Negra argue that besides believing that feminism’s aims have been achieved, thus rendering feminism unnecessary, postfeminists see “the self as a project; kick-ass working-out women as expressions of agency” (21). All aspects of our beings must be worked on.

Perfect participant Marlén explains that, “Now the majority of people are always thinking, and I include myself here, about a future surgery.” While Marissa’s hair dye was considered a violation of her beauty’s authenticity, postfeminist women may view it as a logical step to bettering themselves. Seeing herself as a project, it would make sense for Marissa to dye her hair and engage in many other “improvements.” The static internal goodness reflected by authentic golden hair has been replaced by a malleable goodness. A woman’s value no longer seems to be found in her natural “beauty” but in her ability to make the best out the body she was born with for as long as she lives.

The self-as-project is a lifelong commitment. Prompted by the body’s changes as we age, a woman finds that there is always something to be done, from gray hairs to varicose veins to expanding hips, the project draws on and on, giving women a possibility to distinguish themselves for their cleverness and determination to remain beautiful in spite of it all—if they can afford the cost of their “betterment,” of course. Plastic surgery is a tricky subject to discuss because “it involves agency as well as subordination” (Gagné and McGaughey 193). One could argue that by allowing women to alter their bodies to become whoever they dream of becoming, plastic surgery is empowering them to go beyond the limitations of their birth bodies. After all, isn’t it sad for Marissa to spend her adolescence weighed down by a secret as harmless as hair dye? Indeed, it is. And yet, we cannot ignore the price of our newfound “agency.”

As both Wolf and Pauly Morgan explain, breast implants carry many risks, such as hardening scar tissue, hardened breasts, leaking silicone implants, difficulty detecting cancer and loss of nipple sensitivity. María Fernanda mentions that “you hear these horror stories about breast implants going black, about not being able to detect cancer and things like that.” As Naya, another participant, explains “I would love to have the surgery. I really would. If it wasn’t for the medical risks, of which I am afraid, especially cancer, I’d have done it long ago.” Her family’s history of cancer has kept her from getting the implants. Like the working-class and the poor, who cannot afford the surgery, she is kept out. Her ability to succeed in her self-as-project endeavor is limited by what has happened to the bodies of the women who gave her life. When we argue that plastic surgery gives us agency, we have to ask, who benefits from this agency? Who is left out and why?

Figure 8: María Fernanda

Another problem arises with the agency argument. Besides the health risks we undergo while having surgery, we must admit that the vast majority of women having plastic surgery are doing so to achieve whatever beauty ideal they perceive at the time, not some creative or rebellious expression of their individuality. As Iris Marion Young argues, the current ideal for breasts is impossible to achieve for most women (79). The self-as-project, I would argue, is as oppressive as the authentic, static beauty that once incarcerated Marissa. A malleable prison is still a prison, and if I am to believe Perfect’s participants, the hours I spent worrying about the authenticity of my own beauty during my Venezuelan high school days would today be spent trying to convince my parents to let me “get my boobs done.”

Eduardo, who believes that “breast implants are a necessity,” says that his “friends, who just graduated [from high school] with me want to do it now and if they could, they would do it right away. But their parents try to slow them down a little. But that’s something that’s going to get resolved in a year, and they will have their implants. At 18 or 19 they will have them.” Berónika thinks it happens even earlier, “Before they leave high school, girls already have breast implants. At 15, that's their birthday present.” Lest we feel shocked by Venezuela’s particular take on child abuse, in 1991 Wolf wrote that it was a trend for American high school graduates to be rewarded with breast implants (211). I’d never heard of this type of graduation gift here, though the rumors of young teenagers undergoing breast implant surgery have reverberated across Venezuela for years. Whether or not Eduardo and Berónika’s perceptions accurately reflect the reality of young middle-class Venezuelan women right now—even our President Hugo Chávez has spoken against fifteen-year-olds undergoing the surgery—they will no doubt influence the decisions and desires of younger generations to come.

If Eduardo’s friends manage to convince their parents to pay for their much coveted implants, will the procedure help them achieve the heteronormative goal of attracting men?

Download video: Ogg format | MP4 format

Pauly Morgan argues that “it does not matter who the particular judges are. Actual men—brothers, fathers, male lovers, male beauty ‘experts’—and hypothetical men live in the aesthetic imaginations of women” (36). Not only are women trying to please current and future partners. It’s the abstract, ever-present, collective male gaze that women seek to engage. And yet, guessing what the members of a whole gender would like to see in us is, of course, an impossible task. As a matter of fact, Gagné and McGaughey found that all but one of the women they interviewed claimed that they were not having the surgery to please their husbands and boyfriends, who in most cases were against the procedure (207). However, the women still thought they needed to undergo the surgery in order to please the male gaze.

Figure 9: Eduardo

In contrast to the partners in Gagné and McGaughey’s study, Perfect’s male participants are for the most part enthusiastic in their endorsement of implants and they use humor to describe their enjoyment of them. Defusing the gravity of his statement with self-mockery, Glen says that he’s “one more of the millions of just trashy men that think that large, firm, lay down and they don’t lay down titties are wonderful.” It isn’t just the size which Glen is interested in, but something that no real breasts could do no matter how much they approximate the ideal. The firmest of natural breasts will still change shape when a woman lays down. Only implants will retain their shape. Thus, it is the implants, not large breasts that Glen seems to find attractive.

Humor is crucial as a rhetorical strategy here, because he is in fact saying that he and millions of other men are more excited by artificial sacks inside a woman’s body than by the breasts the sacks are meant to imitate. Glen does not explain why that is. Is it an aesthetic choice? Is it the fact that a woman who has the surgery is considered more attractive because she engages in the self-as-project game so dutifully? Whatever his reasons, if his predilection for implants is as widespread as he seems to believe, naturally large firm breasts (however ephemeral they may be) may no longer be enough to please Venezuelan men, and Eduardo and Berónika’s impression that teenagers often undergo the procedure may become a reality, if it isn’t one already.

Figure 10: Memo

Memo, also using humor to soften the blow, explains that that he “was raised in a culture where breast implants are attractive. Not breast implants, big breasts. Big breasts are attractive. I have it stuck in the hypothalamus and in the last marrow of my primitive brain.” Unlike Glen, Memo seems to be more interested in the breasts themselves, though he does not seem to find the lack of authenticity in implants to be a problem. He is not the only one to mention the culture’s influence in making his choice. Rolando says that he finds “big breasts sensual. I fall into that group in our society that likes big breasts.” For Rolando, there is no difference between breasts and implants. He enjoys big breasts, regardless of their authenticity.

While one could argue that Memo and Rolando are evading responsibility by blaming their fondness for breast implants on Venezuelan society instead of their own choices, women make similar arguments throughout the film. Every participant displayed awareness that breast implants are popular because society and/or the media have decided that they should be. However, only three of them—Berónika, who now regrets her implants, Yarima, who has always been bothered by her naturally large breasts, and Pedro, who still finds implants attractive—critique the implants as a predominantly negative influence on Venezuelans’ lives. The fact that the culture has coerced Perfect’s participants into enjoying breast implants does not lessen the implants’ value in their minds. Both female and male participants agree that the implants help women who undergo the procedure better their life and their self-esteem.

SELF ESTEEM

Figure 11: Luisa

Weber explains that the subject of a makeover finds a “new appreciation of being looked at, basking in a visuality she or he once avoided, the gaze no longer perceived as objectifying but as a tool of empowerment” (82). While women who feel unattractive may fear the male gaze, which in their minds would be mocking or disdainful the way I once feared how the Miss Venezuela judges would regard me, women who feel beautiful welcome the gaze, which they believe showers them with appreciation. Memo explains it this way, “I know women who had a certain personality until they got the implants, and then they become extroverted, ‘Now I am much more accessible, friendly,’ and all that. Because there’s an awakening after you’ve reached a higher level of social acceptance.” It is interesting that for Memo, the women’s transformation includes accessibility and friendliness.

If Memo is right, small-chested women have been curtailing their social, not just their romantic, interactions, so that breast implants aren’t simply helping women fulfill their heteronormative goals of finding male partners but also influencing their friendships, and one would imagine their professional opportunities, if their personalities are so deeply altered. My comment about professional advancement, however, is speculation. It is curious that even though scholars like Wolf spend considerable amounts of time discussing how women’s appearance complicates their professional lives, none of Perfect’s participants—and almost all of them have stable, white-collar jobs—mentioned the ways in which breast implants feature in the work environment.

Figure 12: Edith

The female participants’ comments seem to support Memo’s statement about implants deeply changing a woman’s life. Although Luisa refers to it in purely physical terms— “For me it was a matter of self-esteem, you know? I didn’t wear small tops because I had no breasts at all"—for Edith, the impact is more profound. Though she does mention physical improvements due to the implants, “I don’t need to wear a bra. I can wear backless dresses without one. Bathing suits look better on me,” her discussion also involves her relationships with others: “I feel comfortable with my partner. There are a lot of ways in which I do think that my life is better.” Even though she doesn’t say that the implants helped her become involved with her partner (as the makeover logic has us believe), they do seem to strengthen her relationship with him. Although, as I discussed above, I don’t find the agency argument too convincing, it would be counterproductive to argue against the benefits women who have undergone the procedure enjoy as a result.

While the notion that women exercise agency when choosing to have breast implant surgery is questionable, the benefits discussed by Perfect’s female participants are very real (material) to them. As we attempt to come to terms with women’s choices to have cosmetic surgery, we must keep in mind that in spite of the health risks and the financial and social cost, many women who undergo the surgery do perceive their lives to be significantly better as a result.

Marlén explains, “I feel more complete, and not in the sense of calling attention to myself. I feel more complete in the sense that I’ve always been afraid of old age, and since everything falls, right? Because of gravity everything falls, I would now have some wrinkled prunes hanging there, and that would really depress me.” Like Glen and Memo, she is using humor to dispel a painful statement. As an older woman, she is aware that “[t]he world is run by old men; but old women are erased from the culture” (Wolf 259). Marlén, who earlier confessed that she is always thinking about the next surgery she will have, believes that surgery will help her remain visible in a world that insists on counting her out because of her age and gender.

It is perhaps because she believes that surgery has shielded her from the price of aging that Marlén sees implants as protection. “Women feel more sure of themselves when they’re outside struggling, because they radiate an image, and they realize that others notice them … they feel like they have a weapon to fight with in their lives. In their exterior, they feel secure.” Just as navigating the professional environment is absent from the participants’ discussion, so is sexual harassment and rape. Wolf and other feminists have documented the way in which provocative outfits have been used by judges to argue that victims of sexual assault and harassment were “asking for it,” but this danger was not mentioned by the participants.

Marlén’s description of implants as weapons counters the idea of women being victims of the sexuality implied by their bodies. Instead, Marlén seems to believe that breast implants’ ability to attract the male gaze protects them. It is unclear why Marlén believes this, but for a Venezuelan woman, who, as I will show in the last section of this paper, is told by society and the media that she can only succeed in her female and patriotic duty by being beautiful, implants can mean the difference between success and failure as a human being. By helping a woman become “beautiful,” implants allow her to consider herself a “good” person who is fulfilling her role in society.

Figure 13: Sofía

Another aspect of breast implants that makes the issue complex for feminists is the female bonding that takes place as women share knowledge about how to undergo the procedure safely and about their experiences once they have the implants. Gagné and McGaughey found that all participants in their study “identified their immersion in a culture of beauty and involvement in an network of women whose beauty practices included cosmetic surgery as the most significant influence on their decision to go forward with surgery” (208). Although we often see beauty practices as creating competition between women in order to attract men, they at the same time bring women together. When discussing their decision to undergo the surgery, none of the documentary participants mentioned speaking to male doctors.

Participants instead talked to other women who already had implants. Edith says, “I wanted recommendations. Who else had the doctor operated on? He had operated on two or three of my friends at that time.” Sofía, who was worried about the surgery’s anesthesia’s effects “started talking with friends that had had the surgery and they told me that everything was fine with the anesthesia, and I saw them that they were satisfied with the results.” Not only does having breast implants allow many women to better their self-esteem, the process of having the implants done invites them to call upon the female networks they belong to and most likely help them deepen those bonds.

Sofía and Edith’s mention of their fears over the implants’ safety is the only mention of medical risks besides María Fernanda and Naya’s comments on why they decided against the procedure. Issues with breastfeeding and loss of nipple sensitivity were absent from the participants’ discussion. Rhetorically Perfect’s participants chose to ignore the medical issues in favor of discussing the benefits and the ways society pushes women toward getting the implants and men toward enjoying them. Although implants endanger women’s health and strengthen the hold of the increasingly unnatural beauty ideal, they also provide women with the opportunity to help each other and allow them to discuss their bodies in ways that they can’t discuss with the men in their lives. As I mentioned above, these are substantial benefits for those who decide to undergo the procedure. Another benefit is that breast implants are the one thing that, above all others, is considered to guarantee that a woman will be “beautiful.”

ONLY SOURCE OF BEAUTY

Figure 14: Glen

As Sandra Lee Bartky demonstrated, the rituals of beauty are plentiful and often exhausting. What if one could undergo one procedure that would guarantee that no matter what else a woman did she would be considered beautiful? I imagine most women would at least be tempted to try it, even if we decided against it in the end. Perfect’s participants seem to believe that implants represent that panacea of beauty. As Young explains (and most American women have no doubt noticed), since breasts are often the focus of beauty notions in the States, women are judged by the size and shape of their chest (76). This fixation applies to Venezuela today, but it didn’t always.

Rolando argues that “[t]he arrival of breast implants was a turning point. Before that, women would use different resources. Maybe their hair, maybe their makeup. But now it’s like the goal of every woman who doesn’t naturally have voluminous breasts is to at some point be able to have surgery and get her breasts.” Glen, who believes that the arrival of the television show Bay Watch is responsible for the popularity of breast implants, explains that before Pamela Anderson burst into our screens, Venezuelan women were “very conscious of their look but it didn’t involve breasts. It involved physical beauty. The way of walking, the way of talking, the way that they carried themselves about, and if there was any one physical aspect it might be the buttocks. But that radically changed.”

In contradiction to what Glen says, Eduardo seems to believe that buttocks are still important. He tells us that “you ask a man what’s the first thing he sees in a woman, you ask him to tell you honestly because otherwise he says the eyes. No. That’s after you fall in love. The first thing you really see is her ass and her tits.” His mention of ass and tits echoes the proverbial American "T & A" expression. For Eduardo, as for the rest of the participants, the whole point of the implants is to attract the opposite sex. Nobody addresses women who choose to decline men as partners because of sexual orientation or other reasons.

Eduardo, who at 18 is the youngest participant, seems to believe in a rather romantic turn that once a man falls in love with a woman, her breasts will cease to matter as much as her eyes. His mention of eyes is important here since eye contact is usually necessary for face-to-face conversation. However, it would seem that for Eduardo before a man is ready to converse in that way with a woman, he must first decide that her breasts and her butt have made her a subject worthy of that sort of attention. Unlike the rest of the male participants, however, Eduardo does seem to believe that once in love with a woman, her sexuality will be relegated to a secondary place of value. It is as if he believes that breast implants (ironically) allow women to be valued for something besides their bodies.

Figure 15: Yarima

The more holistic Venezuelan beauty ideal in which the whole body was valued instead of the breasts alone wasn’t any less constrictive to women. After all, having to worry about every aspect of one’s appearance can be exhausting. However, focusing on only one aspect of a woman’s body to determine her beauty (and by extension her goodness) can be devastating for those who do not naturally possess that asset and are unable to obtain it for financial, medical or political/social/moral reasons. The focus on breasts alone can, moreover, make implants seem almost unavoidable to those who do have access to them. As Yarima puts it, also using humor in her description of a situation she finds problematic, “Now if you are a beautiful girl but your boobs are not outstanding, you’re sort of like, oh, well, nothing. But the moment you go and you have your silicones put in and the things poop up and the things flop out, there you go, you’re beautiful.”

Neither myself nor Perfect’s participants have any proof that large breasts guarantee that a woman will be considered beautiful. Not one of the participants who have undergone the procedure, however, was dissatisfied with the results. Even Berónika, who regrets getting the implants, regrets them from a moral/political conviction—“If I had to turn back the clock, I wouldn’t have had the surgery. One grows up and realizes a lot of things, and this is something that isn’t necessary”—not because they did not lead to the results she had expected. The chorus of satisfied women and men regarding implants can only provide more pressure for others to undergo the surgery.

EQUILIBRIUM

Figure 16: Beer advertisement

I have never been good with numbers. Math tormented me throughout my educational career, but there are three numbers that were as natural to me as my own name since I was a girl: 90-60-90. Noventa-Sesenta-Noventa. They rhyme in Spanish, a rhythmic mantra that sticks to the mind like a catchy pop song. It isn’t only the sound of those numbers. It’s the look of them, the three zeros, the six looking like an upside down nine. The look is so round and cohesive, so orderly, as to seem divinely ordained, which, of course, I grew up thinking it was. Whenever I’ve told American women about 90-60-90, their eyes gloss over, and eventually with a spark of recognition they say, “36-24-36.” Somehow it doesn’t seem to hold the same weight here, but as a girl in Venezuela I waited with anticipation and mostly dread to see whether my body would fit the hallowed numbers.

When the measuring tape finally coiled itself around my hips, waist and breasts, I saw with horror that my fears had come true. I was only a few centimeters off for each measure, but enough to fill me with dread. There, on the measuring tape, was irrefutable scientific (these were numbers after all) proof of my failure to be a beautiful (good) woman. By turning the measurement into numbers, 90-60-90 allows women to know to the millimeter how much correcting their bodies need.

Figure 17: Berónika

Perfect’s participants did not mention 90-60-60 directly. Instead they spoke of equilibrium and balance. Gagné and McGaughey found that among their interviewees, “there was a sense that a beautiful body was a proportionate body and that successful breast surgery would look natural or normal” (209). The hourglass will topple if both sides are not equal, so that an abnormal body would be one, which like my own, is out of balance since one side (the hips and butt in my case) is larger than the other. Marlén explains that the implants “balanced my body, because my butt looked as if something had been done to it to make it smaller. It brought equilibrium to my body.” Similarly, Edith argues, “I am tall, I’m not really skinny. I have legs, I have a butt. For me, it’s a matter of aesthetic equilibrium.” Not only are small-chested women who fail to have implants lacking the main source of beauty, but their bodies are out of control, unable to find their balance.

Equilibrium must be respected by choosing the “right” implant size. While no men complained about breasts being too big, a few of the women found some large breasts to be problematic. Edith explains, “I don’t want to be like Pamela Anderson, all huge like that. No, because then they don’t look at your face when you’re talking.” Interestingly, according to Eduardo’s comment, it is the breasts that will eventually lead a man to look a woman in the eye. Marlén concurs with Edith, but instead of blaming the men for focusing on the breasts, she blames the women for inviting that interaction: “Some women are exhibitionists and when they do it, their nipples are almost sticking out. That becomes vulgar.” The supportive female bonding space created by sharing breast implant experiences seems to have a counterpart in which women criticize one another for going too far in their wish to be desirable.

Even though all participants see implants’ goal as inviting the male gaze, there are kinds of male gazes that are unwelcome. Berónika, who regrets having the surgery, says she didn’t want to become “the prototype of a voluptuous woman, ordinarily voluptuous." She explains, “I’m not mad at myself because it was a very discreet surgery. They’re not very large and they can be dissimulated, and I’m not Berónika of the big breasts, but Berónika something else.” Like Edith and Marlén, Berónika’s relationship to the implants seems contradictory. All three want the implants to help them please the male gaze but they don’t want to be defined by the implants either. They struggle between their desire to be considered “beautiful” (good) and their fear of being loved only for one part of their body.

Berónika solves the problem by returning to the very value that breast implants have toppled: authenticity. She argues that “eventually, you slow yourself down and say, ‘I can’t go from my body type to a created, false body type.’ You then select something in between, and you choose to have small implants done.” For Berónika, if the implants go with your body type (if they are in equilibrium with your hips and waist), you have managed to regain some authenticity, your body no longer being “false.” Athough it is immediately clear that some women have implants because it seems impossible that their bodies would naturally have such large breasts, in her case the implants look natural enough to seem real.

Figure 18: Rolando

Sofía addresses the last form of equilibrium mentioned by Perfect’s female participants (none of the men used this rhetorical strategy): equilibrium between age and body. Gagné and McGaughey found that “[s]ome women thought that because their breasts were too small, they were not treated with the respect normatively accorded adult women. Instead, they were treated like children” (200). Sofía, who provides the most emotional account of the ways in which implants have improved her life, coincides with Gagné and McGaughey’s findings; before talking about the shame and pain she felt when trying to buy underwear and bathing suits, she explains, “I was completely flat and there was a moment where I was very self-conscious because I felt that there was not a match between my age and my body.” Thanks to her implants that “has changed completely.” Once again, we are reminded of the reality of the implants’ material benefits for these women. Even though 90-60-90 is a social construct, it is one that is deeply rooted in the culture and being able to fulfill its arbitrary demands through implants seems to women who undergo the surgery to greatly improve their lives.

NATIONAL IDENTITY

Figure 19: Women waiting to cross the street

I began this essay by talking about growing up knowing that winning the Miss Venezuela pageant represented a woman’s greatest possible accomplishment. That knowledge came from endless recess breaks singing the “Miss Venezuela” song, which the participants intone as they walk down the stage. Sometimes my mother and I watched the pageant alone, but more often we’d get together with our extended family. The only comparable television event in the United States is the Super Bowl. We would all be glued to the screen, everyone commenting on the women’s bodies, faces, hair, outfits. The conversations as we all watched the Miss Universe pageant were similar, but the stakes were much higher. After all, every contestant of the Miss Venezuela pageant was Venezuelan. However, for the Miss Universe, our own Olympics and World Cup combined, we got to dazzle the world, and dazzle we did (and still do).

We are second for most Miss Universe victories and are tied with India and the United Kingdom for most Miss World crowns. I don’t know what our Miss Universe and Miss World victory celebrations are like now, but when I lived in Caracas people would take to the streets, honking, screaming and singing, holding Venezuelan flags in the air. I stared out the window, gleefully screaming along with everyone else. Besides the Virgin Mary, no other women were celebrated with such fervor, and I saw no reason to object even if I knew my body and face would keep me away from ever reaching such glory.

While our Miss Universe celebration may seem foolish or excessive to Americans, it makes sense in Venezuela. We don’t get many reasons to shine on the international stage. Our music and soap operas are famous but mostly in Latin America. We are good at baseball but our performance at the Olympics usually renders only a few medals. Our oil and natural gas production staunched our previous production of coffee and cocoa. International glory is something we seldom taste except in one area: the beauty of our women. Not only do we believe our women are the most beautiful in the world, some non-Venezuelans seem to agree. I’ve lost count of the men I’ve met in the States and Europe who comment on how my beauty fits that of the country that has the most beautiful women in the world. I imagine non-Venezuelan women must hear similar things about their countries, but I wonder if they, like I did for so many years, believe it without question.

Has the Miss Venezuela pageant lost its influence since I left Venezuela?

Download video: Ogg format | MP4 format

Figure 20: Advertisement for a radio station

Like myself, Perfect’s participants believe that the value of beauty is so ingrained in our culture that it pervades the media as a driving force. Sofía argues that “beauty is important for our culture. If you want to sell a pen you have to show a beautiful girl with a pen and in other countries it’s not that much.” María Fernanda concurs, “I work in advertising and sadly one can’t help it but to see any kind of product advertised by a woman in a thong or a bikini … you can take a cell phone and put it next to a woman with big breasts. And it’s supposed to, that’s what the regular client thinks, it’s going to sell your cell phone or whatever your product is.” Berónika does not mention the implants but rather sex itself. “Most products are sold through sex. They are sold with beauty standards that have been created, and the media guarantee that these products will be commercialized, and the only option they have is through sex, which has been the great mobilizer of the masses.” Similar arguments have been made about advertising by feminists around the world. However, Perfect’s participants believe (and I have to admit I tend to agree with them) that in our country advertising is more sexist than in other places.

The idea that our advertising is particularly pernicious in its use of the female body serves to reinforce the notion that in Venezuela a woman’s beauty is more vital to her value and wellbeing than in other countries. The participants’ complaints about Venezuela’s use of the female body show their awareness that our beauty worship is problematic. However, this awareness does not lead them to try to undermine beauty’s hold on our country. Instead, the female participants try to survive by making themselves as attractive as they can and the male participants bask in their pride of living in “a country of beautiful women,” as Luisa defines Venezuela.

Figure 21: Pedro

The only participant to place the source of Venezuela’s infatuation with breast implants outside Venezuela itself is Glen, who says, “This is a Bay Watch thing. You know back in the late 80s, early 90s we were submitted to this bombardment of boobs and it caused a radical change in what Venezuelan men wanted to see.” If he is right and Bay Watch did help influence women’s desires to have large breasts, we must remember that it was Venezuela’s fascination with female beauty that made the country so susceptible to Pamela Anderson’s image. After all, Bay Watch was an international phenomenon and did not have the same results in every country where it was popular.

The Miss Venezuela pageant works as a symbol of the self-as-project for Venezuelan women. As Naya argues, “in Venezuela, product of the Miss Venezuela pageant, that prototype of a perfect woman who does exist—there are many because of plastic surgery—has caused women to undergo surgery in their search for that ideal of perfect beauty that the pageant has sold us internationally.” The notion that any woman can be perfect may seem like a baffling throwback to Plato’s forms, but it surfaced over and over throughout the documentary interviews. Not only perfection, but the way in which surgery can help us achieve it. Rolando, also refers to the international value of beauty for Venezuelans, explaining that “when the women from Miss Venezuela, who are an export product, were established as a parameter of beauty, a benchmark was created: I want to be like that.” Rolando’s mention of the contestants as “export products” is a good description of our relationship to female beauty. It makes Venezuela shine internationally (at least in Venezuelans’ own perceptions) and it is something that must be produced, not just through exercise and good diet, but through surgery.

Figure 22: Naya

Plastic surgery is needed because for all our pride in “Venezuelan beauty,” our sense of beauty is influenced by Eurocentric standards that most Venezuelan women do not fit into, so they turn to surgery to reach them. Berónika is the only participant to address how surgery undermines our racial identity, “I think that when one grows up, one realizes that the important things in life have nothing to do with having a beautiful body, with beauty canons that aren’t even natural. We’re not like that. Latinas are not like that. Latinas have normal breasts, thick legs, thick bodies, and we should at least respect our ethnicity, our race.” Berónika is more worried about the implants altering our racial identity than about the culture manipulating her into desiring a surgery she now regrets.

Perhaps addressing how large breasts go against the “world-famous” beauty of Venezuelan women may be a steppingstone to questioning the breast implant trend we are facing. However, that wouldn’t be much of a solution since some new ritual or surgery would no doubt emerge to keep women shackled to their beauty. The solution, as Wolf suggests, would be to relinquish the whole notion of beauty being part of a woman’s value. Attempts at tearing down the beauty myth, however, have been difficult to carry out around the world. In Venezuela, giving up our beauty worship would not only ask women to rethink their sense of value and goodness, it would ask the whole country to relinquish a crucial and most beloved aspect of our national identity.

MANAGING OUR RESISTANCE

Figure 23: Caracas Mall

In spite of how daunting the task of undermining beauty as a woman’s value may seem, I believe we should still try. It is a change that will take generations to achieve, if we ever manage to do so at all, but even if the society at large cannot be influenced, the knowledge that beauty is not a universal ideal can be liberating for individual women. As we try to tackle the beauty myth, however, we may find that addressing particular aspects of it, such as breast implants, is more manageable than trying to bring down the whole behemoth at once. Examining the rhetoric—material in this case—utilized by supporters of breast implants and other aspects of the beauty myth can help us develop our own rhetorical strategies to respond to their arguments. When evaluating viable alternatives to cosmetic surgery, though, we cannot ignore how real its benefits are for those who choose to use it.

If the plastic surgery trend is going to subside, we need to use rhetoric to show women that refusing surgery can also be a source of self-esteem, protection and female bonding. Moreover, since most women who undergo the surgery do so in order to please the male gaze, we should also find ways of asking men to examine and question their predilection for an ideal that most women cannot achieve. Lastly, we must take care to do all this without hurting the millions of women who have undergone cosmetic surgery, since, as I’ve shown above, they often have logical reasons for their choices, not to mention the right to do as they wish with their bodies—our key argument in the pro-choice battle should also hold when it comes to plastic surgery. Let’s not forget that just like there are millions of women who have undergone surgery and bond through the experience, there are millions of women (and men) who are worried by the trend and also bond through their concern. Making our voices of resistance heard above the surgery-is-everywhere rumors spread by much of the media and the cosmetic surgery industry is a valuable strategy as we persevere in our attempt to undermine this particular aspect of the beauty myth.

Notes

1 Since I made this documentary as part of my American scholarly work and its main intended audience is English speakers, I gave participants the choice to be interviewed in English if they felt comfortable doing so. Four of them, María Fernanda, Sofía, Yarima and Glen, elected to speak English. Everyone else’s opinions quoted in this essay were translated by me.

2 Even though the participants are answering questions (which they saw in advance) and for the most part not working from premeditated arguments regarding breast implants in Venezuela, I believe their discourse is very much rhetorical. They are trying to get their opinions across to an audience that is at once real and vague. Since I conducted all the interviews, participants were presenting their arguments to me, but they were aware of a future audience for the documentary consisting of unidentified Venezuelans and Americans and potentially people in other countries if the documentary screened at international festivals (which it has). With this at once present and absent audience in mind, they create parallels between their own and Venezuela’s relationship with plastic surgery and female beauty, consciously making rhetorical moves to show that in spite of being aware of the dysfunctions within the Venezuelan culture, they are still tied to our cultural rhetoric when it comes to breast implants.

3 I will primarily draw from the work of Sandra Lee Bartky, Patricia Gagné, Deanna McGaughey, Angela McRobbie, Kathryn Pauly Morgan, Diane Negra, Yvonne Tasker, Iris Marion Young, Brenda Weber and Naomi Wolf.

4 I originally asked participants a question about the injustice of breast implants being so important to female beauty when only a small portion of the population can afford them. The question came toward the end of the interview, when participants had already discussed how vital it is for women to be able to get the implants. When asked about the ways in which the breast-implant aesthetic excludes the working class and the poor who cannot pay for them, most of the participants found themselves backtracking and saying that even though breast implants were important, they weren’t as important to those who could not afford more basic necessities like food and housing. I realized that by placing the question toward the end of the interview, I had led those in favor of breast implants (the vast majority of Perfect’s participants) into a trap where they could not answer the question without contradicting themselves or sounding callous, which is why those answers did not make it to the final cut of the film. I would like to point out, however, that while discussing the problems posed by the prevalence of breast implants, no one mentioned how they would affect those who cannot afford them unless prodded to address the topic by me.

Works Cited

Bartky, Sandra Lee. “Foucault, Femininity, and the Modernization of Patriarchal Power.” The Politics of Women’s Bodies. Ed. Rose Weitz. New York: Oxford UP, 2010. Print.

Crowley, Sharon. “The Material of Rhetoric.” Rhetorical Bodies. Eds. Jack Selzer and Sharon Crowley. Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 1999. Print.

Gagné, Patricia and Deanna McGaughey. “Designing Women: Cultural Hegemony and the Exercise of Power among Women Who Have Undergone Elective Mammoplasty.” The Politics of Women’s Bodies. Ed. Rose Weitz. New York: Oxford UP, 2010. Print.

McRobbie, Angela. “Postfeminism and Popular Culture: Bridget Jones and the New Gender Regime.” Interrogating Postfeminism. Eds. Yvonne Tasker and Diane Negra. Durham: Duke UP, 2007. Print.

Pauly Morgan, Kathryn. “Women and the Knife: Cosmetic Surgery and the Colonization of Women’s Bodies.” Hypatia 6:3 (Autumn 1991): 25-53. Print.

Perfect: A Conversation with the Venezuelan Middle Class about Female Beauty and Breast Implants. Dir. Alexandra Hidalgo. 2009. DVD.

Ostry, Elaine. “Accepting Mudbloods: The Ambivalent Social Vision of J.K. Rowling’s Fairy Tales.” Reading Harry Potter: Critical Essays. Ed. Giselle Liza Anatol. Westport: Praeger, 2003. 89-101. Print.

Ratcliffe, Krista. “Material Matters: Bodies and Rhetoric.” College English 64.5 (2002): 613-623. Print.

Romero, Simon. “Chávez Tries to Rally Venezuela Against a New Enemy: Breast Lifts.” The New York Times. 16 March 2011. Web. 1 April 2011.

Tasker, Yvonne and Diane Negra. “Introduction.” Interrogating Postfeminism. Durham: Duke UP, 2007. Print.

Tolar Collins, Vicki. “The Speaker Respoken: Material Rhetoric as Feminist Methodology.” College English 61.5 (1999): 545-573. Print.

Young, Iris Marion. On Female Body Experience: “Throwing like a Girl” and Other Essays. New York: Oxford UP, 2005. Print.

Weber, Brenda R. Makeover TV: Selfhood, Citizenship and Celebrity. Durham: Duke UP, 2009. Print.

Wolf, Naomi. The Beauty Myth: How Images of Women Are Used Against Women. First Perennial ed. New York: Harper Perennial, 2002. Print.