Erin Kathleen Bahl, Kennesaw State University

Rich Shivener, York University

(Published June 12, 2020)

The field of comics studies is a productive partner of rhetoric and composition. Although many studies explore pedagogical examples featuring comics in classroom settings (Comer; Kashtan; Kirtley; Jacobs, “Marveling”; Johnson; Losh et al.)[1], there is an incredibly rich world of webcomics [2] out there that has yet to be taken up in rhetoric and composition scholarship, despite increasing interest in comics “and/as” multimodal rhetoric (Jacobs, “Comics”). Such a verbal-visual world includes creators’ accounts and publicly available texts, including the comics themselves; and meta-commentary located in author process blogs, fan discussion forums, and social media posts.

Creator-owned webcomics are especially interesting as serial media because of their often small-scale, single-creator settings. Comics powerhouses like Marvel and DC Entertainment are unable to reproduce such settings because of the larger nature of their teams, distribution channels and funding needs. As we argue in this essay, significant invention-delivery feedback loops emerge and expand with serial media, which an examination of webcomic creators’ processes enables us to theorize in closer detail. Along with Michelle Cohen, we articulate a need for scholars of multimodal rhetoric to investigate comics creators’ composing practices through data such as practitioner narratives. Narratives on composing and literacy practices are already well established in our field as objects of study (Brandt; Berry et al.; Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives; Roozen and Erickson). And recently, rhetoricians have begun to turn toward the theoretical through practitioners’ stories and projects that entangle rhetorical and comics theories (see Anderson; Figueiredo; Helms, “Making Rhizcomics,” Rhizcomics; Salter et al.). In this essay, we build on such research by using two practitioner stories to develop a rhetorical model that depicts invention, seriality, and delivery in a productive feedback loop.

The two practitioner stories we use for this model are quite distinct. In the first, a journalist speaks to how needles and neglected children were sources of invention for a multi-chapter webcomic on heroin abuse. In the second, a former graduate student explains how a webcomic miniseries featuring cartoon birds was a means to processing the pressures of dissertation writing and job-hunting. By applying our rhetorical model of webcomics’ seriality to these two practitioner cases, we open up productive insights into the generative forces shaping webcomics creators’ multimodal storytelling practices. This intervention extends understandings of the interrelationships between invention, delivery, and seriality by examining their intersections in webcomics and creators’ narratives; extends ways of thinking rhetorically about webcomics as serial narrative artifacts; and serves as a call for further investigation into the rhetorically rich world of communication through and around webcomics.

Invention, Delivery, and Seriality: Modeling A Productive Feedback Loop

Rhetoricians have expanded the rhetorical canons in response to developing media and communication technologies, expansions that include accounting for the interrelationships and overlaps between the various canons. For analyzing webcomics, our model of the invention and delivery feedback loop is particularly grounded in recent studies that have redefined the rhetorical canons to better address the exigencies of multimodal composing in the twenty-first century (Buehl; Eyman; Prior et al.; Ridolfo). Specifically, we draw from approaches that conceptualize invention as a distributed composing process resulting from visual arrangement and inventive juxtaposition (Alexander and Williams; Andrews and Bentley; Delagrange; Garrett et al.; Pigg). We also draw on approaches to delivery that account for initial distribution and the circulation of visual-spatial modes alongside textual channels (Edwards; Gries; McCorkle; Ridolfo and DeVoss). Below, we discuss how rhetorical conversations on invention, delivery, and seriality inform our understanding of their circulatory interconnections in webcomics creation.

Invention

Theories of invention in recent scholarship emphasize the distributed, affective, and often visual nature of idea generation in composing multimodal projects. Figueiredo (Inventing Comics; “The Same As It Ever Was”) grounds his rhetorical studies of comics and invention in the work of nineteenth-century cartoonist and educator Rodolphe Töpffer, who argues that line drawing, “with its quick convenience, its rich ideas, its happy and unexpected accidents, is an admirable stimulant of invention” in relation to figure creation (45). Figueiredo connects Töpffer’s experimental media work with Ulmer’s approach to multimedia invention via electracy to argue for invention as the driving force behind the arts and humanities’ potential to shape contemporary higher education (“The Same”). Here, Töpffer approaches invention as a primarily individual practice, but more recently scholars have emphasized invention as a collaborative act. For example, Kara Poe Alexander and Danielle Williams theorize acts of “distributed invention” (DI) based on their experiences creating a film at the Digital Media and Composition (DMAC) Institute. Their theory developed out of the institute’s communal context, defining DI as “two or more people engaging in brainstorming, problem-solving, and idea-generating activities together where original ideas become mutually appropriated and evolve into something different altogether” in shared material spaces (33).

Likewise, scholars such as Susan Delagrange and Bre Garrett, Denise Landrum-Geyer, and Jason Palmeri emphasize active, hands-on processes of generating and crafting ideas, rather than framing invention as a solely intellectual activity. In her webtext “Wunderkammer, Cornell, and the Visual Canon of Arrangement,” Delagrange explores in both theory and practice how new knowledge can be generated through arranging curious objects in surprising combinations. She argues that sixteenth-century Wunderkammern, or cabinets of curiosities, “are models of visual provocation in which objects were manipulated and arranged in order to discover new meanings in their relationships” (Lexia 6). This argument provides a foundation for visual-spatial (rather than exclusively verbal) approaches to invention as a rhetorical canon especially suited to analyzing comics as “juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence” (McCloud 9). Building on Delagrange’s work, Garrett et al. likewise frame invention in part as a process of bringing previously separate components into relation to create a new whole. Their webtext design includes an “invention box”; readers press a button to randomly display two images or quotes that suggest new relationships through their sequential pairing. As a further example of theorizing invention through digital practice, Kendra Andrews and T. Mark Bentley’s video essay discusses and demonstrates “sketchnoting,” or sketching as a multimodal process in which the composer recreates “the facial expressions, the environment, the sounds, and the sensory feelings of particular experienced places.” Sketchnotes emerge from “encounters with materials accessed as one moves through the world,” leading to “a more holistic generation of ideas.” In light of our project, we find it noteworthy that Andrews and Bentley enter into dialogue with Lynda Barry’s comics text Syllabus: Notes from an Accidental Professor, as well as scholars of multimodal rhetorics.

Invention, as these scholar-practitioners frame it, is not an abstracted intellectual act, but rather an ongoing process of creative negotiation with design materials—a distributed process of discovering something new by experiencing and reconfiguring these materials in unexpected ways[3]. From Alexander and Williams to Andrews and Bentley, these scholars’ emphases on hands-on, experiential visual invention as a generative force suggest their composing processes overlap to some degree with those of comics practitioners (see also Bahl, “Comics and Scholarship”). They also suggest that invention is spatially dynamic and dependent on materials and collaborative bodies in motion. Invention is contingent on movement, on encounters. In working towards a model of serial rhetorics in webcomics, our practitioner-oriented approach to invention complements theories of delivery that also concern affectively moving encounters with the material world.

Delivery

Theories of delivery account for the distribution and circulation of visual-spatial modes alongside textual channels. When composing a text for re-composition (e.g., a press release), Jim Ridolfo and Dànielle Nicole DeVoss argue, authors experience positive and negative appropriations by third parties and respond accordingly. In a more recent thread, Laurie Gries’ Still Life with Rhetoric investigates the Obama Hope image to reveal the distributed range of physical and digital manifestations that followed artist Shepard Fairey’s initial design and delivery. According to Gries, human and nonhuman actors contribute to the Obamicon movement and a range of affective desires. Affect accounts for “energy transfer and sense appeals that are material, autonomous, and dynamic that register in bodily experience before cognition takes place.” Things “propagate affective desires that induce unconscious collective identifications and unconscious imitative feelings, thoughts and desires” (130). Put differently, Gries’ view of affect accounts for ways in which texts––such as the iconic Obama Hope image––resonate with and move publics to action, even if publics don’t quite have words to describe their feelings behind an image or related manifestation[4]. Such an affective understanding of circulation is useful because it calls our attention to how publics’ actions influence creators and support or oppose a comic’s future installments. As we discuss below in our case studies, for instance, public actions such as emails and social media responses were significant for a comics journalist, as was encouragement from a smaller-scale public for a graduate student’s first foray into serial comics creation.

Although numerous scholars have augmented delivery and circulation theories in studies of digital production (see Edwards; Eyman; Stedman), recent inquiries like Gries’ Still Life with Rhetoric have turned to affect to account for, in Jenny Rice’s words, “shocked, angry, delighted, and feeling-full bodies” that accompany a digital production in circulation (Edbauer Rice, “Metaphysical Graffiti” 133). Sean Morey insists that “delivery can employ other kinds of psychic and bodily sensations: feeling and affect” (96). Delivery is an extension of the affective body, “even when that body becomes technologized through ink and paper or electricity and silicon” (101). Affects, in other words, are transient across humans and nonhumans and significant to rhetorical delivery and circulation in relation to serial media such as webcomics.

Although such attention to affect and bodies plays an important role in our research, Dustin Edwards’ idea of the backflow of circulation also plays an important role in studying comics in a feedback loop. As Edwards claims, “Circulation is . . . about navigating and inventing from what’s already there, kairotically surfing and plucking from mobile archives to make anew. We write to circulate, but we also write with, from, and because of circulation.” In his considerations of meme authors, “[n]ot only do tactical rhetors keep their eye forward on futurity, imagining how a particular intervention might play out, but they also keep their eye on the backflow of circulation, adapting and forging anew from what’s already in motion” (Edwards, our emphasis). This backflow between invention and delivery is one of the driving rhetorical dynamics of webcomics’ serial production and distribution. When a composer distributes a webcomic in the public sphere, this act initiates a circulatory, affective encounter that might––and often does––shape future invention practices[5].

Seriality

In the comics industry, serialization is a publishing strategy deployed to extend and segment longer story arcs[6]. Choosing to create a series is a decision to enter into a complex rhetorical process with potentially long-lasting effects far beyond the first publication. From a rhetorical lens, theories of seriality enliven modern theories of invention and delivery as well as provide new rhetorical frameworks for studying serial narratives[7]. Here, we consider Casey Boyle’s definition of serial practice along with Frank Kelleter’s concept of feedback loops in serial media, including comics.

Channeling Bruno Latour and Collin Brooke, Boyle argues that seriality, the engine of posthuman practice, is a continual mediation of becoming,” a blurring of invention and delivery practices. Series, then, are “composed of items that are continuous with but also distinct from one another without being separate” (547). In the case of webcomics, these “continuous but also distinct” items may include volumes, chapters, pages, or even individual panels released in sequence at intervals. Series are not only formal elements of narrative, but also ongoing processes of textual production and circulation that act on author, audience, and materials alike. In Boyle’s view, “[a] serial practice is not simply a choice of a particular style but is the adoption of a style of engagement, an ethic in developing capacities for becoming affected by others as much as affecting others” (“Writing” 548), and such practice “perceives difference by affirming prior experience and relations not based on a central actor or that actor’s agency or awareness” (Rhetoric 54). This dual dynamic of affecting and becoming affected, of affirming prior experience and relations, is critical to understanding comics creators’ rhetorical practices in making webcomics.

Boyle’s definition of serial practice and the dual dynamic of affect implicates Kelleter’s discussion of seriality in terms of a “feedback loop.” The feedback loop is central to how we understand serial dynamics operating in the webcomics examined in this article. Kelleter describes this loop as follows: “[S]erial aesthetics does not unfold in a clear-cut, chronological succession of finished composition and responsive actualization. Rather, both activities are intertwined in a feedback loop” (13, our emphasis). He further explains:

[Serial narratives] are evolving narratives: they can register their reception and involve it in the act of (dispersed) storytelling itself. Series observe their own effects—they watch their audiences watching them—and react accordingly. They can adapt to their own consequences, to the changes they provoke in their cultural environment (which is another way of saying that there is a feedback loop). (14, original emphasis).

Kelleter’s discussion highlights the mutually influencing relationships between production and reception inherent to serial narratives as ongoing public events. This dynamic is essential to our understanding of seriality as well, and we build on Kelleter’s model by elaborating on these generative forces in light of the rhetorical canons of invention and delivery.

However, Kelleter’s discussion of seriality focuses primarily on large-scale commercial serial media such as film and television. Working within this focus, he states, for example, that a single author is “a rare or improbable position in serial storytelling” (19). This perspective does not fully address invention and delivery processes for webcomics. Comics journalism tends to operate in smaller teams or pairs, rather than the massive-scale authorial production involved in film and television series. Likewise, a single artist-author is often the norm for webcomics (see for example O’Neill; Sundberg; Weaver). Furthermore, comics journalism and webcomics operate on a very different commercial scale than that of large-scale popular serial media narratives, even the large-scale comics such as those produced by Marvel and DC. Online self-publication, for example, makes it easier for individuals to share their work without necessarily relying on traditional publishing infrastructures. According to Romaguera’s (“Piecing the Parts”) findings, webcomics often start as something circulated among friends as a joke or personal entertainment. It is not until the series is already underway that the creator begins to see new potential for it and perhaps seek circulation for a broader public audience (154). Cohen also notes that sometimes webcomics are not meant for external audiences; rather, for some creators, they serve as expressive functions for their own sake (102).

Aligning with such perspectives, we elaborate on Kelleter’s discussion of feedback loops by examining serial feedback loops in a media he does not address—that of webcomics, both as comics journalism and as comics blog. Broad public circulation as well as smaller, more intimate exchanges of circulation are both significant sites for investigating rhetorical activities, as our two case studies demonstrate.

A Graphic Model

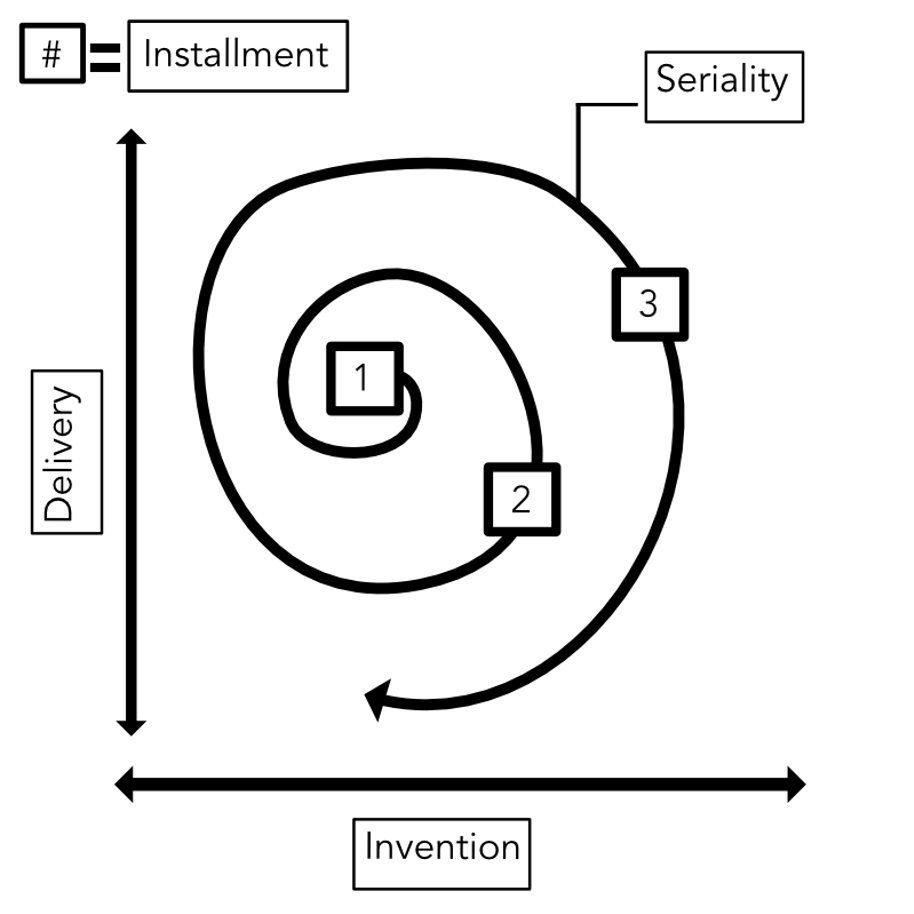

Figure 1

Figure 1. Our model for the feedback loop between invention, delivery, and seriality in webcomics.

Figure 1 models our argument for understanding webcomics in terms of invention, delivery, and seriality. Installments, or separately published segments of a serial comic, are numbered sequentially and arranged on a single-directional line to indicate their serial progression (one installment released at a time in succession). Invention and delivery, however, are continuous axes to indicate their ongoing influences on comics creators’ serial processes (represented by the expanding spiral). The spiral itself visualizes our argument for seriality: progressing temporally, expanding spatially, and inflecting continuously in response to the rhetorical forces of invention and delivery. With each installment, the invention-delivery feedback loop expands, as creators work with and from prior and new relations (audiences, ongoing events) and materials (increasing installments, tools) en route to a new comic.

This rhetorical model allows us to step back and take a global look at the relationship between invention, delivery, and seriality across multiple webcomics. For clarity’s sake, we use the key terms “invention,” “delivery,” and “seriality” to summarize the complex set of interrelated rhetorical practices, including composing and circulation. When webcomics are examined closely as case studies through this model, webcomics amplify the strange temporality of feedback loops in which such practices occur. We can especially learn how webcomics at once move forward in time while also drawing on “prior experience and relations” (Boyle, Rhetoric 54) that contributed to a prior release.

The Needle and the Bird: Two Case Studies

Our first case features cartoonist and comics creator Kevin Necessary who co-authored with reporter Lucy May the three-part webcomic series “Childhood Saved.” Published by Cincinnati news company WCPO, the webcomic series is considered a work of “comics journalism,” or reporting represented in comics form. It follows six children affected by their mother’s heroin addiction and later saved by grandparents who were willing to adopt them. Our second case, Little Yellow Bird, engages a graduate student’s quasi-daily webcomic composed while immersed in the academic job market and final dissertation stages. Rather than engaging in detailed visual analyses of individual panels, we use images from both comics to contextualize our model and focus on the rhetorical processes underlying their creation and circulation. In particular, we take up Kelleter’s method of “dense descriptive detail” as a tool for investigating serial processes to articulate the rhetorical dynamics of these smaller-scale feedback loops within two webcomics case studies (26)[8]. When laid side by side, these two case studies demonstrate the intertwined nature of invention, delivery, and seriality in very different ways. In both cases, we interweave the discussion of our key constructs to set up a comparison between two different comics, and to understand more fully how seriality plays out uniquely in both of their ongoing rhetorical processes.

Childhood Saved

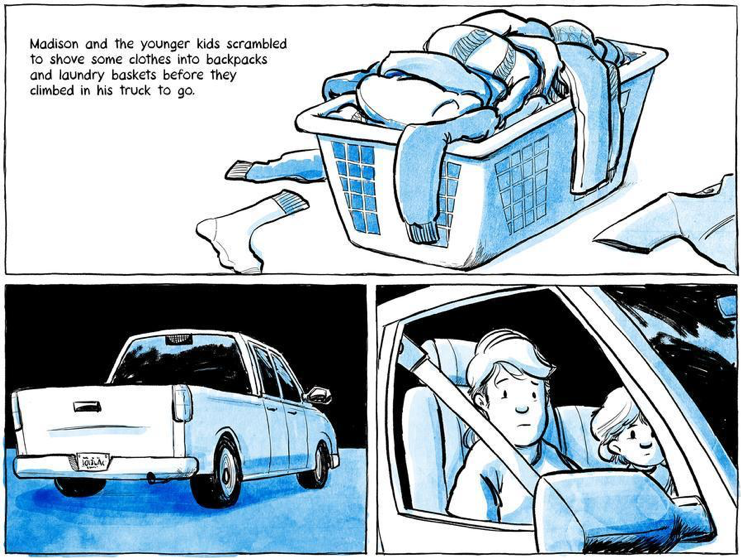

Figure 2

Figure 2. An excerpt from the first installment of “Childhood Saved.” Used with permission by Kevin Necessary.

In the last two years, WCPO has published numerous editorial and special reports on the “heroin epidemic that is ravaging” the region. The news company has also assembled a heroin advisory board that comprises “a group of scientists, treatment specialists, social workers, law enforcement officers and parents who have lost children to heroin,” suggesting that the heroin epidemic is an ongoing exigence in the city (Holthaus). “Childhood Saved” is an example of editors taking a risk after two journalists pitched a webcomic as an ethical method for depicting children troubled by heroin abuse. Necessary and May conceptualized a webcomic approach because the story involved minors who couldn’t be photographed, and “there was a bit of an emotional disconnect” because of the lack of imagery: “We sent a photographer out [to help with reporting], but one thing that I noticed was in the photos, you were either getting the back of people’s heads or their shoulders, or their feet. You weren’t seeing any faces” (Necessary). Necessary and May wanted audiences to see faces and much more, albeit in more abstract representations. Eliding photographic representation (see Figure 2, for example) in a comic is an invitational technique. Even silhouettes unflatten interpretation, for “incompleteness reveals that there is always more to discover” (Sousanis 150).

When “Childhood Saved” was commissioned by WCPO editors, Necessary and May’s collaborative invention was strong over several weeks as the family––six children, grandparents, and a social worker––spoke to the team. We quote Necessary’s recollection of their invention strategies at length to demonstrate their collaboration.

We were both taking notes. Lucy’s notes were much more [in the vein of] traditional journalism. She was typing on her computer …. I had my sketchbooks out and I was doing kind of a hodgepodge of written notes and really crude sketches as I was going along. Someone would say something and it would spark an image in my mind that may or may not have been used later in the story. But it was something to give me a visual touchstone, and so what we did after all the reporting …. I scanned all my pages of notes in, sent those to Lucy, she gave me her typed notes, and we just started meeting back and forth, and going over the notes, and crafting the story. She came up with the idea for how she wanted a lot of the characters to look in terms of the design of the drawings.

I would then sometimes take one of the chapters that Lucy's written and I would rewrite it so that it would fit into what I wanted to do visually. So there was a lot of back and forth . . . . it was very much a synthesis to tell the best story. (Necessary)

Necessary’s commentary on drafting “Childhood Saved” is striking because it demonstrates the collaborative “distributed invention” (Alexander and Williams) that shaped Part One of the series. Put differently, material and affective forces of everyday life for the children impinged on and pulsed through Necessary and May’s draft work. Pencils, sketches, reporter’s notes and more, combined with a family’s first-hand commentary on a hard, everyday life overshadowed by heroin, were sources of invention. Sources were widely distributed, in fact. For the creators, seeing the family’s household, speaking with children, carefully depicting their likenesses, and sharing and circulating designs among staff and editors, were vital to the digital comic’s production. Necessary and May’s collaboration continued for roughly four months, shifting between paper and digital tools (e.g., Adobe Photoshop, HTML code) and, finally, to the web. In two intense weeks of drawing, Necessary even took the project to his home studio and stayed up late at night to tinker with images and text boxes (Necessary). From a nexus of forces spread between a family, a news station, and a home studio, a story emerged.

Part One of “Childhood Saved,” in which six chapters are placed on a single, scrolling webpage, was delivered on May 31, 2016. Each chapter maintains a minimalist aesthetic, with line art drawings accented with shades of blue, purple, red and green that reflect shifting emotions and themes. One chapter opens with a horizontal panel depicting a needle and spoon used to cook heroin, setting up readers for two panels zoomed in on the mother’s eyes before and after heroin abuse. “She couldn’t keep her eyes open,” the oldest daughter remembers (Necessary and May, “Saved”). This sequence of panels reflects the transformation of Necessary and May’s reports on the children and their advocates into an emotional narrative. As the story later shows, the children’s hardships eventually took a turn for the better, thanks to the work of family members and a social worker. In the months followed, Necessary and May spoke again to the family, whose invitation to participate in their story would serve as a gateway to a new comic.

Part One of “Childhood Saved” was distributed widely via social media, Necessary’s personal Facebook page, and the news station’s TV segments. Necessary and May’s work was featured by journalism institutes such as Nieman Lab (Wang) and Poynter (Nelson) and in their respective reports on the future of comics journalism. Later, Part One was remediated to a print mini-comic and distributed by ProKids, Inc., a nonprofit in Cincinnati. The delivery and circulation of the “Childhood Saved” installment cultivated new desires and felt memories about heroin abuse and child endangerment, as Necessary and May received numerous responses from readers.

As Necessary remembers, “We were getting a decent number of private messages sent to us from people some very surprising people even around the community whose names I’m not going to mention. There would be people that I was surprised to see on email saying something like, ‘This has happened in my life. I'm a grandparent and I had to do this with my kids.’ That was amazing” (Necessary). Audience reception on content and form was indeed fuel for Necessary and Mays’ invention strategies for Part Two of “Childhood Saved,” titled “A New Chapter” but so too was their interest in following the children’s adoption process. Necessary and May were invited to see the adoption in court. “I brought my sketchbook with me, and I had no idea if I was going to capture anything. I just started taking notes and doing more things, and I came back and I said, ‘I think we’ve got a second chapter’” (Necessary).

Beyond the family’s invitation to the ceremony, Necessary’s illustration choices for “A New Chapter” were shaped by audiences who, in his words, were gripped by Part One but found it a challenging read on mobile phones because its side-by-side panels shrink to fit small screens. Thus, “A New Chapter” is a long sequence of single panels delivered in a vertical format that depicts the children being adopted. It is unlike many American comics that follow a horizontal, Z-like logic, moving from left to right. Nevertheless, the child depictions and color choices reflect those of Part One. Again, the oldest daughter is depicted in scenes of hope and despair, warm colors and smiles moving to needles awash in blue shades and shadows. Ultimately, Part Two brings closure to the family’s story and raises awareness of many kids still out there. “That moment,” Necessary said, “that release of seeing the kids finally adopted with their families and rushing up and taking the photos with their grandparents and everybody just breaking out into cheers. Seeing that actually happen was amazing. Knowing that we affected people’s lives in some small manner” (Necessary).

Figure 3

Figure 3. A GIF in the third installment of “Childhood Saved.” Used with permission by Kevin Necessary.

Part Three of “Childhood Saved,” titled, “The Hurt and Healing Continue,” wouldn’t come until August 2017, more than a year after Part Two’s release and circulation. Heroin abuse and its impact on kids still lingered in the city, and it was grounds for Necessary and May to once again return to the family they had followed for months. As their story depicts, the mother depicted in “Childhood Saved” Parts One and Two had died after using heroin laced with the narcotic carfentanil. “The Hurt and Healing Continue” zooms in on the children’s affective responses to her death and their maturation under the care of grandparents. This time, Necessary and May’s invention strategies were shaped by their attunement to previous structures of “Childhood Saved” as well as comics journalism writ large. May’s paragraphs on the family are integrated with Necessary’s illustrations and animated GIFs that depict the children and grandparents. As the story winds down, one GIF alternates between a teenaged daughter standing in a bar and wearing a lab coat outside of an emergency room (Figure 3). Necessary reflects on his process this way: “We didn’t want to do the same thing a third time. One of the things that I’ve noticed about these [news] comics is it can be a lot of talking heads at times, which I think is just the nature of journalism” (Necessary).

“The Hurt and Healing Continue” and previous installments merged traditional journalism storytelling and graphic narrative approaches while not losing sight of the webcomic’s primary exigence––child poverty in relation to heroin abuse. August 2017 marked the conclusion of Necessary and May’s “Childhood Saved,” and its final delivery and reception gave way to new comics composed by Necessary under the auspices of WCPO. Necessary recently completed a series on an undocumented family, responding to the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy debate. The DACA policy created an exigence for “Living in the Shadows” and another discussion about comics as an ethical journalism method (see Tompkins). It was Kevin’s first single-author webcomics series, and likely won’t be his last at WCPO. Indeed, the success of “Childhood Saved” validated comics journalism as a viable form of storytelling in the news company. “Childhood Saved” was a proving ground for Kelleter’s claim that proliferation is a key characteristic of serial narrative. As Kelleter observes, “[c]ommercial series tend to proliferate beyond the bounds of their original media and core narratives” in part to sustain the culture of serial storytelling as a whole (20).

Overall, Necessary’s practitioner narrative demonstrates the invention-delivery feedback loop in which he and May found themselves as they composed a webcomic. Their approaches to Part One and the comic’s delivery and circulation influenced Part Two, which came to light only after the family and readers contacted Necessary and May. Part Two wasn’t planned ahead of time. It was emergent, a product invented from and with external forces (e.g., readers, fellow reporters) and affective desires (e.g., seeing the adoption) in circulation. Part Three, finally, was a response to previous parts and lingering sentiments about the family and heroin abuse in the city. New ideas for and approaches to each part, that is, took form because of the previous parts’ delivery and backflow of circulation.

Little Yellow Bird

Figure 4

Figure 4. An image of title character Little Yellow Bird. Used with permission by Erin Kathleen Bahl.

Little Yellow Bird (hereafter LYB) serves as another example of how seriality functions as a rhetorical strategy for negotiating with affective pressures in daily life through cyclical processes of invention and delivery. Co-author Erin Kathleen Bahl began creating LYB during the final semester of her doctoral program, while she was on the academic job market and preparing to defend her dissertation that spring. This time is typically a period of high stress for graduate students; individuals in this position face the dual pressures of completing a challenging intellectual project on a tight timeline while navigating uncertain career prospects in the face of intense competition. Many graduate students experience severe affective pressures such as depression and anxiety during the course of their education (Evans et al.). Every individual responds differently to these pressures; LYB became one channel through which Bahl could negotiate her response to an intensely stressful transition.

One challenge of studying this webcomic and other ongoing serial narratives is that they continue to unfold and take shape as new needs arise beyond the initial exigence, as we illustrate through our model of iterative feedback loops. As Kelleter observes, it is methodologically difficult to “do justice to the evolving, interactive, and auto-adaptive character of serial narratives” (16). Such sequences are difficult to definitively interpret when they have no clear conclusion; any scholarship engaging an ongoing serial narrative must by necessity try to make sense of an unfinished story. The comic remains ongoing at the time of writing this article, but the initial exigence from which the comic was invented has passed; Bahl graduated in spring 2018 and joined Kennesaw State University’s English department in fall 2018. Thus, although LYB as an ongoing webcomic continues to reflect experiences in the creator’s daily life, this discussion emphasizes the comic’s originating period in spring 2018.

LYB is a single-authored serial comic inspired by a tradition of autobiographical comics creators such as Lynda Barry, Alison Bechdel, and Leslie Stein[9]. Its autobiographical focus means it operates in some ways more like a blog, with episodes constructed in response to particular events in daily life, rather than carrying out a pre-planned narrative trajectory. For Bahl as composer, the webcomic initially served as a means to practice digital composing and illustration; to provide distance from the dissertation; and to process the pressures of the job market. As LYB developed, though, it took on a life of its own through interactions with Bahl’s friends and family, which opened up new possibilities for how the webcomic continued (and continues) to take shape. Writing a dissertation can be an intensely isolating experience without a clear end in sight. In contrast, creating installments of LYB provided many short-term, significantly simpler writing tasks that could then be shared with a personally meaningful audience.

the series consists of 283 installments created between January 4, 2018, and June 5, 2020. These installments follow the adventures of the eponymous Little Yellow Bird (Figure 5): a fluffy, bright yellow bird who finds joy in small things like packing peanuts and rollerblades. All cast members are likewise anthropomorphic birds. Although Bahl’s decision to feature birds developed idiosyncratically, this choice reflects the broader work of a “small but passionate group of comic artists who have found birds to be excellent mediums for depicting life’s ups and downs” (Valentine; see also Barkman; Mosco; Mullin; Stapleton; Thomas). The all-avian cast, bright colors, simple narration, and geometric illustration style set a lighthearted tone for playfully engaging daily events on a minute scale.

LYB was created and developed entirely in a digital environment. All illustrations are vector art created in the program Affinity Designer; each image is a compilation of digitally generated geometric shapes manipulated and grouped into an object, landscape, character, or other narrative element. For Bahl’s geometric illustration style, these available shapes serve as affordances and constraints for inventing a range of characters, environments, and objects. A grouped set of digital shapes can be easily adapted in future illustrations, for example; however, the flat, cartoonish aesthetic communicates a less weighty ethos than would a hand-drawn comic representing three dimensions.

Lived material circumstances are important invention resources for comics creators’ ongoing rhetorical practices more broadly considered. For example, as Fraser notes of early cartoonist Rodolphe Töpffer, “the urban must not be seen as merely as a container, that is, the material place where Töpffer lived and worked. Instead, the modern city influenced his work on many levels, in terms of method, content, theme, narrative, and distribution or readership” (25). In the case of LYB, the primary sources of inspiration based on lived experiences are people, objects, and events encountered in Bahl’s everyday life, with transitional life events (e.g., dissertation defense, graduation, moving) serving as the driving narrative arc. These recurring topics become storylines and serve as invention resources for building continuity within an ongoing, open-ended narrative arc (Jones). Apart from these major events, though, virtually any experience is fair game, from accidentally walking into a window (“LYB61”) to long walks on the beach (“LYB81”). Much of LYB builds on brief, salient moments in daily circumstances, responding to micro-exigencies as they emerge. Some installments reflect explicitly on the job market or dissertation writing processes. “LYB4,” for example, reimagines the application letter-writing process as a towering stack of letters into which the main character dives gleefully. Other installments, however, feature the creator’s collection of succulent plants (“LYB13”) or a trip to the grocery store (“LYB38”); “LYB9” addresses “laundry day” and the pains of a squeaky dryer, while “LYB19” recounts claiming (and defending) a favorite spot on a city bus. This daily serial comics format provided a flexible storytelling strategy through which Bahl could respond to stressful experiences with a degree of narrative control over what she did and did not choose to represent. Thus, although the dissertation and job market remained constant pressures throughout LYB’s initial development, the range of situations addressed reflect the creator’s decision to focus the narrative lens on other dimensions of daily experience.

Figure 5

Figure 5. “LYB7: Work Day.” Used with permission by Bahl.

LYB was first circulated via single digital images shared with friends and family. “LYB11,” for example, was created during an evening spent with friends at their home and passed around via laptop screen; “LYB31” celebrates a friend’s successful dissertation defense and was sent via text. As these individuals responded positively, Bahl continued inviting additional acquaintances to participate as characters and began to investigate broader publication options. Before a person became a character in the comic, they were typically asked for permission, as well as which kind of bird they would like to be. Like Necessary and May’s use of comics rather than photographs to protect identities in “Childhood Saved,” representing characters as birds rather than by face or name offers some measure of anonymity to an audience outside the circle of acquaintances. Furthermore, this approach built a cast of characters tailored to the primary audience (Bahl’s friends and family) and invited them to participate in the webcomic’s ongoing creation and circulation.

The series was publicly launched on its own website and social media pages in May 2018 following Bahl’s defense, graduation, and accepted hiring offer; the initial launch included the first fifty installments. At the time of writing, delivery consists of website uploads upon creation plus twice-a-week social media posts to Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, DeviantArt, and Instagram (as well as continued texts and laptop-passing with friends and family). Given that the series began in January 2018, there is a delay of several months between an installment’s delivery via social media and the events represented. For example, the anime convention (“LYB17”) occurred on January 28th and the opera (“LYB18”) on February 2nd; however, these comics were not posted on social media until July 10th and July 12th, respectively.

This gap between source event and delivery has the advantage of delaying time-sensitive information, such as hiring announcements and dissertation writing anxieties. However, this gap distances audience members from the moment of experience, which may decrease the investment of following along with a story as it unfolds in “real time.” The situational nature of some of the humor also decreases through release at a less opportune moment. In the midwestern US, for example, jokes based on snow (“LYB10”) are less relevant to readers’ current experiences when delivered in June, and a post about springtime (“LYB48”) was posted on social media the day after Halloween. Nevertheless, the delivery delay’s key advantage lies in its aid to invention on a hobbyist’s schedule; with several months of content already prepared, the webcomic can be developed at leisure as time permits.

Furthermore, LYB’s small-scale circulation and short serial period make it adaptable to audience suggestions and participation as invention material—a practical demonstration of Edwards’s “backflow of circulation,” in which serial delivery generates new material for continued invention. Sometimes readers informally suggest new scenarios; a joke about a “construction crane” (“LYB57,” presented in Figure 6), for example, was offered by a pun-loving friend, and taken up after a trek across campus dodging widespread renovations. Other times, a planned event sparked a new idea; “LYB79” was created to thank another friend who’d hosted an exquisitely detailed tea party, based on photos taken during the event. Although LYB operates on a much smaller scale than “Childhood Saved,” audience response and circulation play a significant role in shaping both webcomics’ serial invention and delivery processes.

Overall, LYB emerged as one individual’s negotiation with the affective pressures of dissertation and job-market processes. The webcomic’s invention materials were people, objects, and experiences encountered in everyday life, as well as geometric digital shapes manipulated in Affinity Designer. The comic was delivered to a primarily small-scale audience, then later to a broader public via social media. Because of the comic’s subject matter, flexible means of design, small-scale circulation, and short serial period, each new installment emerged out of the ongoing feedback loop between changes in everyday experiences (sources of invention) and audience responses to previous installments (channels of delivery), rather than according to a predetermined narrative arc. For Bahl as a comics creator, LYB served as a method of serial meaning-making during an ongoing professional and personal transition period. The series represents these transitional experiences, along with more ephemeral daily moments and experiences, and offered a channel through which to connect with friends and family members in the midst of affectively challenging, often intensely isolating experiences.

Implications for Re-imagining Rhetorical Canons, Re-framing Serial Practices

By rhetorically elucidating the serial dynamics of “Childhood Saved” and Little Yellow Bird through practitioners’ narratives, we foreground the interdependency and mutual exchanges between invention and delivery strategies. Retrospective investigations of published multimodal rhetorics in the form of webcomics helped us see the richness of such an interdependency, or a generative feedback loop between two canons steeped in emotionally charged life events. As rhetoricians continue to investigate feedback loops intensifying relations between invention and delivery, webcomics provide a clear illustration of the ways in which a delivered (i.e., published and circulated) text might be both the end and the beginning of a new installment. In such serial texts, invention and delivery are not bookends of knowledge production. They are recursive, even on small and large scales with respect to “Childhood Saved” and Little Yellow Bird. And if we take up Edwards’ position on the “backflow of circulation,” then we can see that delivery, more simply, creates flows and rhythms that cultivate new ideas for a serial installment. New invention strategies, as our case studies demonstrate, are contingent on the affective energies that stem from delivery and circulation.

Beyond strengthening invention and delivery’s relationship, our imagined rhetorical model implicates the diverse approaches and publishing scales in the broader webcomics scene. E.K. Weaver’s gay romance webcomic The Less Than Epic Adventures of TJ and Amal amounted to more than 500 pages, released from December 2009 to 2014, chronicling the main characters’ cross-country trip. Its reception online parlayed into a contract with small-press publishing house Iron Circus as well as three epilogues to The Less Than Epic serial webcomic (see Shivener). A theory of the invention-delivery feedback loop positions us to question the extent to which the wide readership fueled the contract and epilogues, as well as extra art, notes, and more collected in the hardcover edition. Researchers might do the same questioning for Katie O’Neill’s fantasy series The Tea Dragon Society, which ran as a webcomic from September 2016-September 2017 and was collected in print by Oni Press. O’Neill’s work is worthy of future investigation, as the New Zealand comics creator uses reader commentary and monetary support (via the crowdfunding site Patreon) to sketch ideas for the next iterations of the Tea Dragon Society, and was additionally recognized with the 2018 Eisner Awards for Best Webcomic and Best Publication for Kids (ages 9–12). All temporally sensitive, such creators invented and delivered content in serial form to push a narrative forward and to refine their practices. Rhetorical approaches to seriality such as ours may support further insights for studying and understanding these comics practitioners’ communication strategies and narrative craft by drawing greater attention to the forces out of which these stories emerged.

[1] See Molly J. Scanlon and Jason Helms for engagement with comics focusing on professional and scholarly practices.

[2] We follow Romaguera (“To Start, Continue, and Conclude” 15) in referring to online, serialized digital comics as “webcomics” for the sake of consistency and concision throughout our project.

[3] See visual studies scholars such as Amy Propen and Benjamin Fraser for more theories on the relationship between invention and material environments, such as cities and GPS devices.

[4] Gries draws from Brian Massumi, Jenny Rice (“Unframing Models”), and many others to account for rhetorics and affects in circulation.

[5] See Marilyn Cooper’s “Rhetorical Agency as Emergent and Enacted” and Thomas Rickert’s Ambient Rhetoric: The Attunements of Rhetorical Being. The “continuous loop of conscious and nonconscious processes in the nervous system,” Cooper argues, implicates agency and ethos (428). Rickert calls attention to “a dynamic interchange of powers and actions in complex feedback loops; a multiplication of agencies that in turn transform, to varying degrees, the agents; a distribution of varied powers and agencies” (10). Although these theories on loops are intriguing, we find more use in Kelleter’s theory because it concerns seriality.

[6] See Verano for a brief history of the periodical comic’s evolution.

[7] Webcomics are part of a larger discussion on popular media seriality (Golden; Yancey; Romaguera “Piecing the Parts,” “To Start, Continue, and Conclude”). Robyn Warhol and Colleen Morrissey’s digital humanities project Victorian Serial Novels, for example, is designed to evoke the temporal experience of serial reading as would have been the initial audiences’ experiences for engaging the text. For the scope of this article, though, we focus on webcomics, and we recognize the rich scholarly conversations on serialized print comics (see for example Chute; Gardner).

[8] This descriptive approach to two case studies provides a useful methodological lens for examining serial dynamics because “commercial series are inevitably multi-authored, produced, and consumed in many-layered systems of responsibility and performance, and always dependent on both the material demands of their media and the constraints of their cultural environments” (Kelleter 26).

[9] For further discussion on autobiography and graphic narrative forms, see Michael A. Chaney’s edited collection Graphic Subjects: Critical Essays on Autobiography and Graphic Novels.

Alexander, Kara Poe, and Danielle M. Williams. “DMAC after Dark: Toward a Theory of Distributed Invention.” Computers and Composition, vol. 36, 2015, pp. 32-43.

Anderson, Amy. “Exploring the Multimodal Gutter: What Dissociation Can Teach Us About Multimodality.” enculturation, no. 25, 2017.

Andrews, Kendra L., and T. Mark Bentley. “Multimodal Composing, Sketchnotes, and Idea Generation.” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, vol. 22, no. 2, 2018, http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/22.2/disputatio/andrews/index.html.

Bahl, Erin Kathleen. “Comics and Scholarship: Sketching the Possibilities.” Composition Studies, vol. 43, no. 1, 2015, pp. 178-182.

---. Little Yellow Bird, http://erinkathleenbahl.com/littleyellowbird/.

Barkman, Joshua. False Knees, https://falseknees.com/about.html.

Berry, Patrick W., Gail E. Hawisher, and Cynthia L. Selfe. Transnational Literate Lives in Digital Times. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital P/Utah State UP, 2012. Web.

Boyle, Casey. Rhetoric As a Posthuman Practice. Ohio State UP, 2018.

—- “Writing and Rhetoric and/as Posthuman Practice.” College English, vol. 78, no. 6, July 2016, pp. 532-554.

Brandt, Deborah. The Rise of Writing: Redefining Mass Literacy. Cambridge UP, 2014.

Buehl, Jonathan. Assembling Arguments: Multimodal Rhetoric and Scientific Discourse. U of South Carolina P, 2016.

Chaney, Michael A., editor. Graphic Subjects: Critical Essays on Autobiography and Graphic Novels. U of Wisconsin P, 2011.

Chute, Hillary. “Temporality and Seriality in Spiegelman's In the Shadow of No Towers.” American Periodicals, vol. 17, no. 2, 2007, pp. 228-244.

Cohen, Michelle. Style Made Visible: Reanimating Composition Studies Through Comics. 2018. Ohio State U, PhD Dissertation.

Comer, Kate. “Illustrating Praxis: Comic Composition, Narrative Rhetoric, and Critical Multiliteracies.” Composition Studies, vol. 43, no. 1, 2015, pp. 75-104.

Cooper, Marilyn M. “Rhetorical Agency as Emergent and Enacted.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 62, no. 3, 2011, pp. 420-449.

Delagrange, Susan H. Technologies of Wonder: Rhetorical Practice in a Digital World. Computers and Composition Digital P/Utah State UP, 2011.

Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives, http://www.thedaln.org/.

Edbauer Rice, Jennifer H. “(Meta)Physical Graffiti: ‘Getting Up’ as Affective Writing Model.” JAC, vol. 25, no. 1, 2005, pp. 131-159.

Edbauer Rice, Jenny. “Unframing Models of Public Distribution: From Rhetorical Situation to Rhetorical Ecologies.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 35, no. 4, 2005, pp. 5-24.

Edwards, Dustin. “On Circulatory Encounters: The Case for Tactical Rhetorics.” enculturation, no. 25, 2017.

Eyman, Douglas. Digital Rhetoric: Theory, Method, Practice. U of Michigan P, 2015.

Evans, Teresa M. et al. “Evidence for a Mental Health Crisis in Graduate Education.” Nature Biotechnology, vol. 36, 2018, pp. 282-284.

Figueiredo, Sergio. Inventing Comics: A New Translation of Rodolphe Töpffer's Reflections on

Graphic Storytelling, Media Rhetorics, and Aesthetic Practice. Parlor P, 2017.

—-. “The Same As It Ever Was: Invention as the Future of Digital Rhetoric.”

Digital Rhetoric Collaborative, Blog Carnival 14, 9 Oct. 2018, http://www.digitalrhetoriccollaborative.org/2018/10/09/figueiredo-the-same-as-it-ever-was/.

Fraser, Benjamin. Visible Cities, Global Comics: Urban Images and Spatial Form. UP of Mississippi, 2019.

Gardner, Jared. Projections: Comics and the History of Twenty-First-Century Storytelling. Stanford UP, 2012.

Garrett, Bre, et al. “Re-Inventing Invention: A Performance in Three Acts.” The New Work of Composing, edited by Debra Journet et al., Computers and Composition Digital P/Utah State UP, 2012, http://ccdigitalpress.org/book/nwc/chapters/garrett-et-al/.

Golden, Catherine J. Serials to Graphic Novels: The Evolution of the Victorian Illustrated Book. UP of Florida, 2017.

Helms, Jason. “Making Rhizcomics.” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, vol. 23, no. 1, Fall 2018, http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/23.1/inventio/helms/index.html.

—-. Rhizcomics: Rhetoric, Technology, and New Media Composition. U of Michigan P, 2017.

Holthaus, David. “How Should We Combat Heroin Epidemic?” WCPO, 29 Jan. 2016, https://www.wcpo.com/news/opinion/editorial-well-work-on-finding-a-way-forward-on-the-heroin-epidemic

Jacobs, Dale. “Marveling at ‘The Man Called Nova’: Comics as Sponsors of Multimodal Literacy.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 59, no. 2, 2007, pp. 180-205.

Jacobs, Dale, editor. “Special Issue: Comics and/as Rhetoric.” The Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics, vol. 3, no. 1, 2019, http://journalofmultimodalrhetorics.com/3-1-issue.

Johnson, Fred. “Perspicuous Objects: Reading Comics and Writing Instruction.” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, vol. 19, no. 1, 2014, http://technorhetoric.net/19.1/topoi/johnson/index.html.

Jones, Sara Gwenllian. “Serial Form.” Routledge Encyclopedia of Narrative Theory, edited by David Herman et al., Routledge, 2010, p. 527.

Kashtan, Aaron. “Talismans: Using Comics to Teach Multimodal Writing.” Class, Please Open Your Comics: Essays on Teaching with Graphic Narratives, edited by Matthew L. Miller, McFarland Publishing, 2015, pp. 103-116.

Kelleter, Frank. Media of Serial Narrative. Ohio State UP, 2017.

Kirtley, Susan. “Considering the Alternative in Composition Pedagogy: Teaching Invitational Rhetoric with Lynda Barry's What It Is.” Women's Studies in Communication, vol. 37, no. 3, 2014, pp. 339-359.

Losh, Elizabeth. M., Jonathan Alexander, Kevin Cannon, and Zander Cannon. Understanding Rhetoric: A Graphic Guide to Writing. Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2017.

Massumi, Brian. Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. Duke UP, 2002.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: HarperCollins, 1994.

McCorkle, Ben. Rhetorical Delivery as Technological Discourse: A Cross-Historical Study. Southern Illinois UP, 2012.

Morey, Sean. Rhetorical Delivery and Digital Technologies: Networks, Affect, Electracy. Routledge, 2015.

Mosco, Rosemary. Bird and Moon, http://www.birdandmoon.com/.

Mullin, Chuck. Chuck Draws Things, https://www.instagram.com/chuckdrawsthings/.

Necessary, Kevin. Personal Interview. 6 Dec. 2017.

Necessary, Kevin and Lucy May. “Childhood Saved: The Hurt and Healing Continue.” WCPO, 1 August 2017, https://www.wcpo.com/longform/childhood-saved-the-hurt-and-healing-continue.

—-. “Childhood Saved: A New Chapter.” WCPO, 23 September 2016, https://www.wcpo.com/longform/childhood-saved-the-next-chapter.

—-.“Saved: How One Call Rescued Six Kids.” WCPO, 31 May 2016, https://www.wcpo.com/longform/childhood-saved.

Nelson, Blake C. “Ready to Practice Comics Journalism? Ask These Questions before You Commit.” The Poynter Institute, 10 Nov. 2017, https://www.poynter.org/news/ready-practice-comics-journalism-ask-these-questions-you-commit.

O’Neill, Katie. The Tea Dragon Society, Oni P, 2017, http://teadragonsociety.com/.

Pigg, Stacey. “Coordinating Constant Invention: Social Media’s Role in Distributed Work.” Technical Communication Quarterly, vol. 23, no. 2, 2014, pp. 69-87.

Propen, Amy D. Locating Visual-Material Rhetorics: The Map, The Mill, and the GPS. Parlor P, 2012.

Prior, Paul et al. “Re-Situating and Re-Mediating the Canons: A Cultural-Historical Remapping of Rhetorical Activity.” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, vol. 11, no. 3, 2007, http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/11.3/binder.html?topoi/prior-et-al/index.html.

Rickert, Thomas J. Ambient Rhetoric: The Attunements of Rhetorical Being. U of Pittsburgh P, 2013.

Ridolfo, Jim and Dànielle Nicole DeVoss. “Composing for Recomposition: Rhetorical Velocity and Delivery.” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, vol. 13, no. 2, 2009, http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/13.2/topoi/ridolfo_devoss/.

Ridolfo, Jim. “Rhetorical Delivery as Strategy: Rebuilding the Fifth Canon from Practitioner Stories.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 31, no. 2, 2012, pp. 117-129.

Romaguera, Gabriel. E. “Piecing the Parts: An Analysis of Narrative Strategies and Textual Elements in Microserialized Webcomics.” 2010. U of Puerto Rico, MAEE Thesis.

—-. “To Start, Continue, and Conclude: Foregrounding Narrative Production in Serial Fiction Publishing.” 2017. U of Rhode Island, PhD Dissertation.

Roozen, Kevin, and Joe Erickson. Expanding Literate Landscapes: Persons, Practices, and Sociohistoric Perspectives of Disciplinary Development. Computers and Composition Digital P/Utah State UP, 2017.

Salter, Anastasia, et al. “Making ‘Comics as Scholarship’: A Reflection on the Process Behind Digital Humanities Quarterly (9)4.” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, vol. 23, no. 1, Fall 2018, http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/23.1/inventio/salter-et-al/index.html

Scanlon, Molly. J. “The Work of Comics Collaborations: Considerations of Multimodal Composition for Writing Scholarship and Pedagogy.” Composition Studies, vol. 43, no. 1, 2015, pp. 105-130.

Shivener, Rich. “Epic Queer Web Comic ‘TJ and Amal’ Coming to Print.” Publishers Weekly, 1 April 2015, https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/comics/article/66071-epic-queer-web-comic-tj-and-amal-coming-to-print.html.

Sousanis, Nick. Unflattening. Harvard UP, 2015.

Stapleton, Janie. St. Janie, https://www.instagram.com/st.janie/.

Stedman, Kyle. D. “Remix Literacy and Fan Compositions.” Computers and Composition, vol. 29, no. 2, 2012, pp. 107-123.

Sundberg, Minna. Stand Still, Stay Silent, http://sssscomic.com/index.php.

Thomas, Jess. Birdstrips, https://www.instagram.com/birdstrips/.

Tompkins, Al. “A Local TV Station Hired a Cartoonist to Tell Stories that Are Tough to Photograph.” The Poynter Institute, 12 Apr. 2018, https://www.poynter.org/news/local-tv-station-hired-cartoonist-tell-stories-are-tough-photograph.

Valentine, Katie. “Are These Quirky Comics Launching a New Generation of Bird Enthusiasts?” Audubon, 18 Sept. 2018, https://www.audubon.org/news/are-these-quirky-comics-launching-new-generation-bird-enthusiasts.

Verano, Frank. “Spectacular Consumption: Visuality, Production, and the Consumption of the Comics Page.” International Journal of Comic Art, vol. 8, no. 1, 2006, pp. 378-387.

Wang, Shan. “‘But It’s…Cartoons?’: Comics and Cartoons are Coming to Life Well Beyond the Printed Page.” Nieman Lab, 31 Aug. 2016, http://www.niemanlab.org/2016/08/but-its-cartoons-comics-and-cartoons-are-coming-to-life-well-beyond-the-printed-page/.

Warhol, Robyn, and Colleen Morrissey. Victorian Serial Novels, http://victorianserialnovels.org/.

Weaver, E. K. The Less Than Epic Adventures of TJ and Amal, 2015, http://tjandamal.com/.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. “Made Not Only in Words: Composition in a New Key.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 56, no. 2, 2004, pp. 297-328.