Kimberly Gunter, Fairfield University

(Published December 11, 2019)

Jennifer Beals makes women moan. And she knows it.

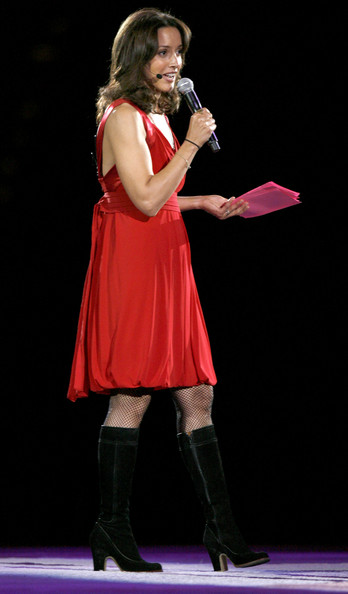

In 2008, the last year of production of Showtime’s The L Word (TLW), Eve Ensler celebrated the tenth anniversary of V-Day by bringing The Vagina Monologues to New Orleans’ Superdome. With TLW writer/producer Ilene Chaiken and TLW actors Alexandra Hedison and Daniela Sea in tow, Beals read “The Woman Who Loved to Make Vaginas Happy,” Ensler’s monologue of a tax lawyer cum sex worker who finds her calling and her paycheck in making women moan. In a plunging, baby-doll gown, fishnet stockings, and knee-high boots of which Bettie Page might approve, that Beals chose to perform this monologue, punctuated with an array of girl-on-girl orgasms, was no accident. Beals’ narrator and Beals herself declared, “…I was responsible for other women moaning” (violaky). To demonstrate her prowess, Beals, assisted by Chaiken, Sea, and Hedison (off to the side, around a single microphone, backup-singer style), performed a round robin of types of orgasms, Beals taking the African American moan; the uninhibited, militant bisexual moan; and the diva moan, all taxonomic lenses through which we might read her. When Beals later confessed to her Superdome audience, “I discovered how deeply excited I got ... when I was responsible for other women moaning” (violaky), she spoke not as “Bette Porter,” her TLW character, but she didn’t speak only as Ensler’s sex worker either. Instead, she spoke as a by-then queered Jennifer Beals who rhetorically insisted on her own intersectionality, perhaps as African American, uninhibited bisexual, diva, and more.

Herein, I trace the metamorphosis of Jennifer Beals as she transformed into a queer, intersectional public rhetor. To do so, I examine three sets of texts: Beals’ interventions into TLW scripts and storylines; the rhetoric that Beals effected in interviews and press conferences; and the rhetoric that Beals fashioned in LGBTQ cultural spaces such as pride parades and the queer press. My rhetorical analysis of these texts illustrates that Beals was hailed into intersectional, queer rhetorship by (at least) three forces: first, her experiences of alterity as a biracial girl; second, a voyeuristic, homophobic, and racist film industry; and third, a queer counterpublic desirous of images and icons of queer sexuality. While some might have resisted interpellation into what began as allegations of queerness, I show how Beals performed a rhetorical pivot and instead responded with relish, intervening into larger, monolithic rhetorics of race and sexuality, both on and off the TLW set. In addition, I show how Beals’ interventions amalgamated with LGBTQ viewers’ history of contrary reading practices, creating a “hyperreality” between Beals herself, the cultural assemblage of “Jennifer Beals,” TLW’s Bette, and queer audiences. The common denominator in all of these utterances was the material speaking body of Jennifer Beals, a “hybrid” body that became so marked by racial and sexual liminality that she emerged as an intersectional, queer rhetor.

To support this argument, I detail Beals’ own theorization of narrative and the dialectic into which she brings intersectionality and queerness, and I zoom in on the rhetorical strategies Beals deploys in the agentive co-construction of herself as public rhetor—strategies, I suggest, that sponsor counterrhetorics like those described by Jose Muñoz and thereby promulgate counterworlds. To contextualize the queer rhetorical strategies that Beals employs, I first rely on Jonathan Alexander and Jacqueline Rhodes’ description of queer rhetoric. I then extend Alexander and Rhodes by noting that Beals’ intersectional rhetoric, like that described by Karma R. Chávez, challenges instantiations of a too frequently whitewashed queer, underscoring the possibilities that bringing queerness and intersectionality into explicit dialectic provides, possibilities too often dormant in both queer and intercultural rhetorical scholarship.

Figure 2. Showtime press photo, reprinted in Kiy

In recovering Beals as an intersectional queer rhetor, I attend to two gaps in current scholarship. First, I attempt to address the absence of scholarship that attends to TLW, particularly the show and its cast’s rhetoric. Launching in 2004 as the U.S.’s first nationally distributed television drama primarily about lesbians, TLW remains remarkable simply because it exists. Showtime rolled out TLW with the marketing slogan “Same Sex. Different City,” a nod to HBO’s Sex and the City, then in its final season. Thanks to soaring ratings, the show grabbed the fastest renewal in Showtime’s history, earning a second season only days after the pilot aired. And as high as ratings climbed, they were often underestimated due to “…the large numbers of women who gather[ed] each week…at one another’s houses, or the local lesbian bar, to watch the episodes together” (Warn, “Introduction” 7). Considering that TLW dominated lesbian popular press during its six-season run and that TLW holds a singular place in the history of LGBTQ media and discourse, it is an important cultural rhetorical moment in need of investigation.

Second, I respond to the persistent scarcity of rhetoric and composition scholarship that privileges the rhetorical practices of queers of color. This absence endures despite the early promise of queer studies and despite repeated calls for this work. Eric Darnell Pritchard eloquently catalogues the calcified repercussions of this absence, writing of our field that:

tyranny of literacy normativity ... that perpetually treats African American, LGBTQ literacy, composition, and rhetorical studies as mutually exclusive ... makes it difficult, if not impossible, to speak to the intersections of these scholarly discourses in a way that gets us beyond what is a clear impasse so that work at the intersections of race, gender, sexuality, and queerness can be fully seen, heard, and taken up. (3)

Noting the failure of the discipline to build on the intersectionality of the work of scholars like Harriet Malinowitz and Gwendolyn Pough, two instances of “far too few moments in which a literacy, composition, and rhetoric scholar acknowledges Black queerness as an area within the disciplinary landscape” (20), Pritchard urges, “…redress means action” (23). With this article, I attempt to respond to Pritchard’s call. Scholarly attention to Beals’ rhetoric on- and off-set is especially important, I argue, in that it embodies the “intersectional paradigms” (“Gender” 41) that Patricia Hill Collins has called for. In “decentering dominant cultural assumptions, exploring…normalization, and interrogating the self and the implications of affiliation” (Winans 106), Beals—as intersectional, queer rhetor—suggests discourses that might be exploited by others interested in counterworld-making.

Interpellation, Identification, and the Casting of Queerness

TLW premiered at a time when the country remained under the administration of George W. Bush, “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” reigned (and would until 2011), and no state had yet legalized gay marriage. Only five lesbian characters existed on network television (Grubb) at that time, and many were minor characters whose sexuality went largely unaddressed or provided punchlines for heterosexual main characters (consider Roma Maffia’s “Liz Winters” on Nip/Tuck). Accepting a lead on the first U.S. television series to foreground lesbian storylines, Beals was thus plunged into a cultural soup marked by homophobia and heterosexism.

In Judith Butler’s terms, Beals was also summoned into the discursive position of purported bisexual by the homophobic historicity which “exceed[ed] in all directions the history of [Beals as] the speaking subject” (Excitable Speech 28). In media responses to Beals’ moan, nameless Hollywood insiders, for instance, nattered to reporters that Beals must be bisexual (Stockwell). Their rationale? No actor who wasn’t really bisexual or lesbian could portray lesbian sex so convincingly. Many actors, of course, might have sought to tamp down gay rumors. Beals, however, like Colin Craig’s Black, gay student Leslie, “fram[ed] the rhetorical affect of the homophobic slur as opportunity for exploration, identity formation, and critique” (634). Beals, in fact, pivoted and through identification countered that being labeled bisexual “… was a huge compliment to me … . I feel really proud …” (Stockwell). In doing so, Beals demonstrates how rhetors, once summoned, do not cede agency and often respond in startling ways. Beals also demonstrates how rhetors can be beckoned into agentive existence in the face of interpellation. In one sense, Beals faced Althusserian interpellation through puerile rumor, underscoring the imperviousness of discourse to the subjects upon whom it acts, whom it constitutes (in this case, as bisexuals), regardless of what the subject already was, or “really” is, or perceives herself to be. On the other hand, Beals’ pivot demonstrates that if the power of interpellation exceeds the subject, that subject’s power also exceeds any single act of interpellation. Responding with pleasure, Beals co-constituted her rhetorical situation by occupying a vernacular space in which she positions herself as a bisexual “agent against discriminatory language practices” (Craig 634). Via public address, then, Jennifer Beals emerged as a powerful queer rhetor.

Beals transmogrified into queer rhetor in part because she repeatedly articulated queer utterances. Jonathan Alexander and Jacqueline Rhodes stipulate that queer rhetoric must, first, acknowledge the power-laden, creative discourses of (normative) sexuality and, second, disrupt such normalization. “Queer rhetoric,” they write, “… relies on (1) a recognition of the … ways in which sexuality … constitutes a nexus of power … through which identities are created, categorized, and rendered as subjects … and (2) a reworking of those identifications to disrupt and reroute … power, particularly discursive power.” I would extend Alexander and Rhodes by arguing that, to become queer rhetor, one must also issue queer rhetoric again and again. For example, two years after TLW’s premiere but two years prior to her Superdome monologue, Beals marshalled the 2006 San Francisco Pride parade. In her speech at the parade’s rally, Beals did not fashion rhetoric anew. When she invoked there “love in every variety, every shape, every size, every color, every race, every class, every orientation,” when she lambasted the “fools who would try to suppress [love]” (rps75), she was hardly a speaking Adam. However, because of her repeated iterations of progressive speech (in the press, at V-Day, in events such as this Pride rally), Beals renewed “the linguistic tokens of a community, reissuing and reinvigorating such speech” (Butler, Excitable Speech 39) and, in doing so, she recast herself as a queer rhetor.

Beals’ incentive for crafting this queer subjectivity seems rooted in two sources: her experience of alterity and her theorization of narrative. Beals confessed to Curve’s Laurie Schenden that, due to her biraciality, she had “always lived sort-of on the outside…. …[B]eing the ‘other’ in society is not foreign to me.” This confession emerged by way of explaining how Beals (a presumably “straight” woman) would approach playing lesbian Bette Porter. The daughter of an African American father and an Irish mother, marginalization, as a formative experience, manifested early for Beals. When accepting a 2005 Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) Golden Gate Award, Beals chronicled her childhood growing up in Chicago: “… I searched for images of girls that looked like me. As a biracial girl … there wasn’t a lot there … . … I had Spock. … My theme song was Cher’s ‘Half-Breed.’ … [S]ometimes my otherness was so palpable it was a wonder that anyone could see me. I was that invisible” (wildchildivy). Beals here describes abjection. Depending on address to bring her into recognizability, a young Beals suffered a kind of discursive death.

Perhaps predictably in light of such circumstance, awareness of narrative’s power was sparked early for Beals:

I think I’m an actor because I’ve always loved the idea of being part of a story. When ... my mother would tell me a bedtime story, I would just beg her to make me a character ... ‘Put me in the story,’ I would say, and ... she would ... There were a variety of fictions, and I think from an early age we all see our lives as a narrative ... Through our imagination and ... the imaginations of others, we are constantly in the process of creating ourselves. (wildchildivy)

For a child who foraged for images of girls who looked like her, this longing for representation is a longing to be called into discourse and to be recognized as extant. As an adult actor on TLW, Beals leverages such experience to combat the paucity and the homophobia of LGBTQ representation: “… that I am part of a narrative where I can offer up some sort of mirror, however imperfect, to someone who may never have seen themselves represented is very exciting” (wildchildivy).

Such leveraging is most obvious in Beals’ interventions in the narrative scripts of TLW. It was Beals, for instance, who insisted that TLW’s Bette be biracial: “… Bette was initially not biracial. I suggested that the character be made biracial so that I could serve all those people who are like me and have never seen themselves represented except for maybe in a Benetton ad” (wildchildivy). In so doing, Beals intervened in her own childhood abjection, offering her younger self a media image of racial complexity.[1]Yet, in leveraging her star status and stipulating Bette be biracial, Beals also transfigured into a writerly agent, productively fragmenting a frequently whitewashed LGBTQ community by rupturing what would have otherwise been far more homogenous depictions of race and sexuality on TLW. In demanding her character be biracial, in other words, Beals splintered what might have been seen as an all-white core cast portraying an all-white lesbian community.

Intersectionality and Rejection of the Singular

By insisting Bette be biracial, Beals also leveraged narrative to tell marginal and explicitly intersectional stories: “In a ... culture so dominated by media and by the manipulation of words and stories,” she explains, “telling the tales of people whose stories have historically not been told is a radical act and an act I believe that can change the world and help re-write history. Imagine if all of our stories were told... . [O]ne day all the narratives would intertwine ...” (wildchildivy). Here—though she is speaking at a GLAAD event—Beals references not just de-raced (white) LGBTQ identities but other experiences of alterity as well. Beals echoed such sentiments to New York Magazine’s Adam Sternbergh, “I wanted to explore what it means to be bi-racial in a larger cultural context and what it means within the gay community” (64). Beals’ rhetorship, then, is more than queer; it is also intersectional (and, perhaps, thereby, all the queerer).

The episode “Listen Up” powerfully demonstrates the interventions into narratives of race and sexuality enabled by Beals’ insistence on exploring intersectionality through her character on TLW. Interestingly, it also demonstrates how TLW played on viewers’ knowledge of Beals’ life outside the series. Series creators, in fact, injected Beals’ autobiography into Bette’s more than with any other actor/character dyad, relying on viewers’ knowledge of Beals’ life and fans’ subsequent co-construction of Bette (and, then, of Beals, too). Such insistence on explorations of intersectionality via interjections of Beals’ autobiography enabled, as I aim to demonstrate in this section, Beals to forge a hyperreal intersectional rhetor who ultimately forwarded the business of counterworld-making.

In “Listen Up,” Bette’s allegiance to intersectionality becomes most evident in the scenes in which Bette and partner Tina attend a therapy group for expectant parents. Yolanda, a darker-skinned, African American group member, blasts Bette for:

talking so proud and forthright about being a lesbian, but you never once refer to yourself as … African American … . … [L]ook, they’re wondering what the hell we’re talking about because they didn’t even know you were a Black woman. … [Y]ou need to reflect on what it is you are saying to the world by hiding so behind the lightness of your skin.

Bette replies, “… you know nothing about me. You don’t know how I grew up. You don’t know how I live my life.”

Figure 3. Clip from “Listen Up,” Gunter, “Yolanda Part 1”

The dialogue relaunches in the next group session:

Yolanda: “… I get the impression that you don’t even think of yourself as African American.”

Bette: “I am half African American, and my mother is white.”

Yolanda: “But legally you’re Black. Isn’t that a fact?”

Bette: “That’s the white man’s definition of me, yes. The one-drop rule.”

Shushing an intruding Tina, Bette continues: “… [H]ow do you justify pushing me so hard to come out as a Black woman when … you’ve let us mistake you for a straight woman?” The camera reveals surprise on the white faces of several group members.

Yolanda: “You thought I was straight?”

Bette: “Well, why wouldn’t I? … [Y]ou’re not exactly readable as a lesbian, and you didn’t come out and declare yourself.”

When Yolanda protests that she would never deny her lesbianism, Bette retorts: “Well neither do I. … I would never define myself exclusively as being white any more than I would define myself exclusively as being Black.... [W]hy is it so wrong for me to move more freely in the world just because my appearance doesn’t automatically announce who I am?” Yolanda rages, “Because it is a lie! ... She denies her Blackness because it is easier, preferable, for her to go through the world having people mistake her as white!” In contrast to Yolanda’s rising voice, Bette’s voice drops; she leans into the circle and, eyes welling, offers, “You don’t know how I’ve gone through the world. You have no idea.”[2]

Figure 4. Second Clip from “Listen Up,” Gunter, “Yolanda Part 2”

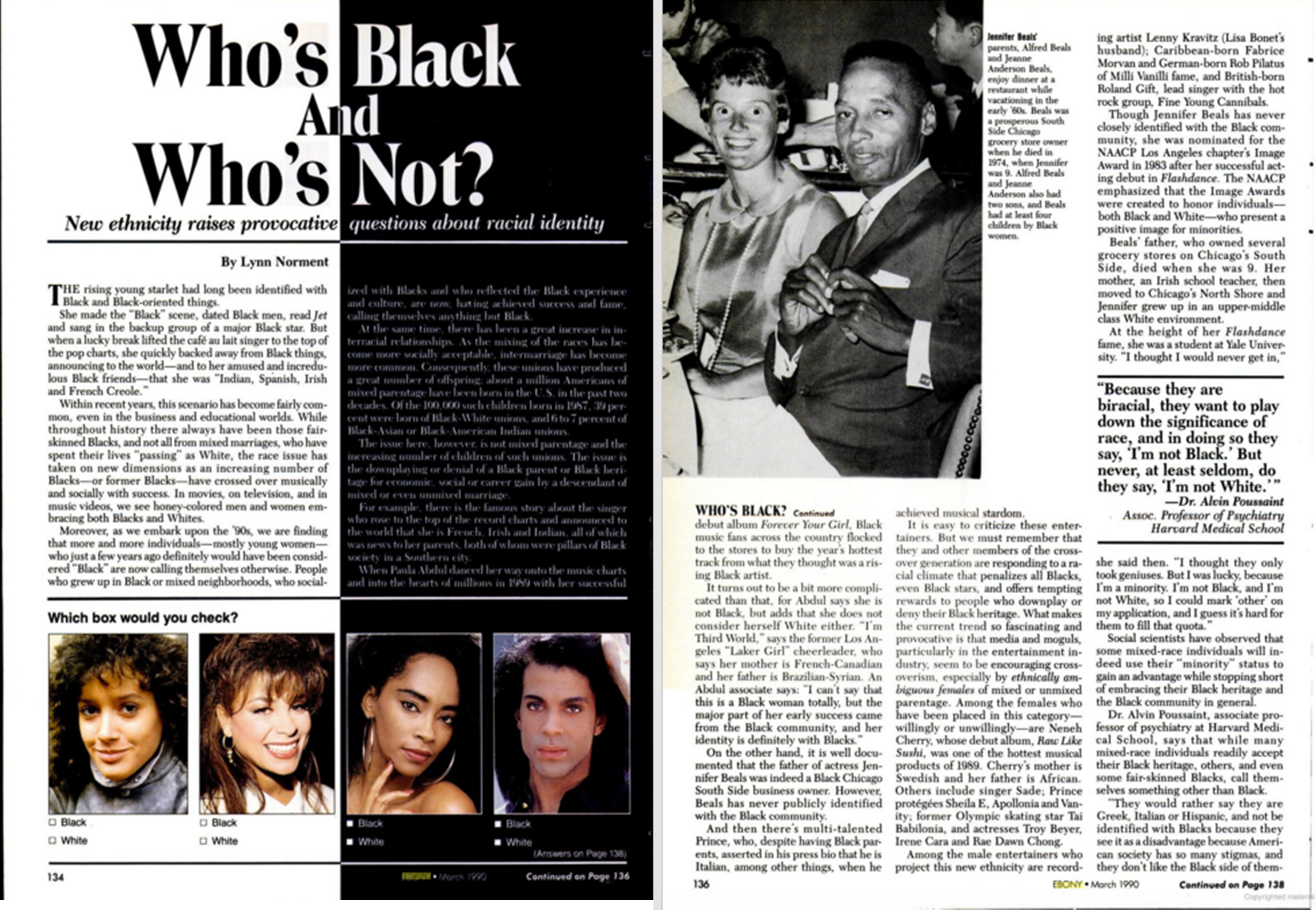

Interestingly, the commingling of Beals’ and Bette’s autobiographies and fans’ knowledge of both create a queer, intersectional hyperreality on TLW. As Bette responds to Yolanda’s charges, Beals, through narrative, concurrently answers allegations she has previously faced in the media. For instance, in the 1990 Ebony article “Who’s Black and Who’s Not,” Lynn Norment sneeringly appoints Beals as the paradigm of disingenuous or tragic race consciousness. The first page of the glossy article features a small, color photo of a young Beals. The article’s following page includes a far larger, black-and-white photograph of Beals’ parents. The visual rhetoric is not happenstance.

Figure 5. 1990 Ebony article, Norment

After delineating the phenomenon of “fair-skinned Blacks” “calling themselves otherwise,” Norment offers Beals as a case study (134). She accuses, “… [I]t is well documented that the father of actress Jennifer Beals was indeed a Black Chicago South Side business owner. However, Beals has never publicly identified with the Black community” (136, emphasis mine). Norment here implies that Beals has conspired to deny her “real” race. As proof, she quotes Beals on her acceptance to Yale: “I thought I would never get in… . But I was lucky, because I’m a minority. I’m not Black, and I’m not White, so I could mark ‘other’ on my application, and I guess it’s hard for them to fill that quota” (136). In “Listen Up,” when Bette, fatigued, acknowledges, “I am half African American, and my mother is white,” it is not difficult to imagine Beals herself responding to critics such as Norment who, as Bette accused Yolanda and “the white man” of doing, seem to believe that “one drop” of African American blood in her ancestry is enough to designate Beals as Black alone.

The conflation of Bette and Beals is especially imaginable here in that Norment’s perspective seems quite imbued in Yolanda’s specific lines. That young Beals neither denies nor embraces only one portion of her racial heritage reveals, Norment suggests, insincere duplicity, for Norment follows Beals’ quote with a purported survey of the psychology behind such “deceit”: “Social scientists have observed that some mixed-race individuals will indeed use their ‘minority’ status to gain an advantage while stopping short of embracing their Black heritage and the Black community …” (136). With the photo of Beals’ parents looming, Norment further implies Beals is calculatingly lying by quoting psychiatrist Alvin Poussaint: “[S]ome fair-skinned Blacks, call themselves something other than Black. They would rather … not be identified with Blacks because they see it as a disadvantage …” (136). While implicit here, through Yolanda, we can almost hear Norment shouting, “She denies her blackness because it is easier, preferable, for her to … hav[e] people mistake her as white!”

Beals’ intersectional queerness as articulated in these hyperreal examples challenges not just heteronormativity but homonormative metanarratives that verge on positivism, and I’m not talking (only) about identity politics rhetorics that queer theorists have made their mark decrying. I’m instead speaking to queerness’ frequent erasure of race and, thus, its frequent whiteness. Similarly, Beals’ rhetoric contests intercultural communication studies’ tendency to fixate on nationality or race alone. By writing discussions about race and sexual orientations into the script, Beals (and, through her, TLW) craft intersectional, queer rhetoric that challenges white queer discourses and straight intercultural ones. In so doing, Beals signals “redemptive power in bodies that are hated and condemned,” “languaging how we want to be read … and exist in the world” (Craig 630).

Such rhetorical moves toward intersectionality are especially important in that Alexander and Rhodes argue against the construction of irreconcilable and singular conceptions of identity:

The binaries of black/white, ethnic/nonethnic, … gay/straight and female/male, must be challenged… . More pressingly, [José] Muñoz and [David] Wallace insist … that we understand how … sexuality, race, ethnicity, and gender complicate one another, and how rhetorical practices might have to shift to articulate and intervene in particular representations and debates about sexual experience and identity.

Even as Alexander and Rhodes acknowledge the importance of multiplicity and “call for additional work on how such queernesses intersect multiple identity positions and practices,” they turn to a largely white queerness in their exploration, for instance, of the queer rhetorical interventions of Walt Whitman, Oscar Wilde, and their 1980s and ‘90s activist “heirs.” I acknowledge, of course, the near impossibility of considering every possible subjectivity in any single analytical moment. As potentially unending lists of enumerated identities demonstrate, more are erased with each new identity cited. Moreover, as Karma R. Chávez has reassured, “It is not hard to think of times when race or gender appear to be the most salient factor in a given communicative exchange. … [N]ot … every identity needs to be addressed in every given analysis” (31). That said, I worry about what feels too easy a division of race from the “queer rhetorical practice” that Alexander and Rhodes discuss, even as they attempt to intervene in “discourses of normalized, and normalizing, sexuality.” Beals’ rhetoric pushes us to consider that, in a culture so imbricated by race and racism, it may be impossible to consider normalized sexuality at all without attending to racialized subjects and that attempting to do so hazards reinstantiating the queer as white. As Pritchard reminds us, “… queer literacies … must remember that successful literacy theories … are built from deliberate and realized considerations of race and ethnicity alongside queer sexualities and genders” (22). Doing so abets our attempts to achieve Karen Kopelson’s sense of queerness “as it strives to push thought beyond circumscribed divisions” (20). Too easy a separation between queerness and race especially risks making some intersectional, queer rhetors such as Beals feel (yet again) that they are “standing under a sign to which one does and does not belong” (Butler, Bodies 231). Beals as rhetor refuses to accede to essentialist pressures and serve only as a representative of Blackness or even multiraciality. Instead, Beals time and again invokes intersectionality of identity, “the interlocking nature of race, class, gender, sexuality, ability and nation” (Chávez 21). Referring repeatedly to her experiences with and sense of alterity, Beals uses intersectionality as a “tool … to understand operations of culture, identity and power” (22). In so doing, Beals fulfills E. Patrick Johnson and Mae G. Henderson’s project of “sabotaging neither and enabling both” racial and sexual identities (1).

Queer Readership and Jennifer Beals’ Dialectical Embodied Rhetoric

The dearth of LGBTQ film and television characters has historically been so ample that the absence has transmogrified into a presence in itself. Resultantly, LGBTQ audiences have long read contrarily, askew, and co-created queer storylines (Russo). TLW distinguishes itself, not only as the first mainstream American drama to focus primarily on lesbian storylines. TLW’s cast and creators also deliberately cultivated an I/Though relationship with the show’s queer fan base. The dialogic relationship can be seen in actors’ improvisations designed to fuel fan obsession; writers’ decisions to center episodes around iconic (if bourgeois) lesbian rites of passage (like Olivia cruises and Dinah Shore weekends)[3]; post-episode online chats; fan conventions; the creation of OurChart.com and its podcasts with TLW insiders; message boards that TLW creators read; and polls regarding how fans hoped storylines would evolve. Viewers influenced what became at its core an interactive series. TLW’s invitation to fans to co-create the show amalgamated with its inclusion of autobiographical details from actors’ lives. Toss in the tapping of its queer audience’s history of contrary reading, and viewers not only co-constituted the show but “real life” narratives for the actors themselves, blurring distinctions between representation and the unrecoverable real.

Beals’ on- and off-screen queerness and intersectionality fed fans’ co-construction of her public ethos. TLW followers could hardly miss Beals’ astute politics, for instance, when she schooled reporters. When asked during one press conference if she had a sexual relationship with any cast or crew member, Beals stormed:

When is the last time you slept with someone? … Who was it, what was it like, was it good? … If I were George Clooney and Catherine Zeta-Jones was standing next to me, you wouldn’t ask me if I’d had an affair with her. Because it’s a gay-themed show you find it salacious. In your older, heterosexual male mind, you think it’s OK to ask me that question. (Kennedy)

Beals might have answered this reporter’s question, not just differently but at all. She might have cited her real-life husband’s reaction to TLW, as Kate Capshaw did regarding her performance in A Girl Thing [“... it made him go, ‘Oh, my gosh, that looked enjoyable. That looked beautiful and was very tender and very intimate’” (Kaye 52)]. Instead, Beals’ rhetorically pivoted and interrogated heterosexist privilege again and again while she played Bette Porter.

The queer, intersectional promise of Beals’ performance as Bette is fulfilled by her performative actions as Beals, and her performative actions as Beals infuse fans’ viewing of her performance as Bette and fans’ co-creation of a public Beals. If recognition is a signifying act of creation, Beals was interpellated into intersectional queerness by everyone from jejune studio execs to lesbian viewers. Beals as rhetor, however, doubles down, not by saying “Yes I Am” (á la Melissa Etheridge) or “No I’m Not” (á la Capshaw’s “Steven loves my lesbian sex scenes”). Instead, she skates across identity, opts for a chosen queer alliance, and articulates trans utterances that escape the “is or isn’t she” binary.

The common element in these utterances, performance or performative, on- and off-stage, remains the speaking brown body of Jennifer Beals. Beals submitted her very body in service to her queer, intersectional rhetoric, for example, in Bette’s (frequent) sex scenes. TLW’s sex scenes may have read as “vanilla” for viewers in the know, but they were far more explicit than any lesbian sex scenes previously aired on mainstream television. No stolen glances across a locker room or dissolves to black followed by naked shoulders peeking above sheets, actors passionately played their sex scenes, due in part to TLW’s creators. (Cast members participated in a lesbian sex workshop prior to filming.) For all of TLW’s flaws (and there are many), Chaiken’s vision especially guarded the series from creepy scenes of lady-touching or lesbian sex filled with coy glances at “horny, hetero guys” (Beals’ words) who were among the show’s viewers (wildchildivy). Beals, with name recognition and roles in big budget films, had the most to lose in portraying lesbian sex as realistically as scripts and censors allowed. But in sex scenes and off screen, Beals leverages her role of “cultural producer” (Halberstam 159) not only to embody queer rhetoric but to challenge white queerness via an intersectionality that she both incarnates and insists be recognized by manipulating her willing body to create powerful images. Alexander and Rhodes write, “Visibility becomes … the pressing rhetorical strategy—and need—of LGBT rights movements. It is our demand for acknowledgement ... But it also conditions numerous visual rhetorics … in the spectacle-laden realm of the public sphere.” Whether Beals shows up at a Philadelphia gay bar (“Rally for Obama, Pure Club”), marshals a Pride parade (rps75), or allows us to stare at Laurel Holloman’s white hands on her naked breasts in the episode “Lights! Camera! Action!,” she manipulates mass media while framing herself within an intersectional, queer visual aesthetic. As we stare at Beals’ body, she rhetorically stares back, “willfully opt[ing] for abjection” (Craig 624) and thereby redirecting our gaze, “assert[ing] agency and visibility” (Craig 633) and fissuring “the process of identity formation” (Craig 621) for all who behold her.

Figure 6. Bette and Tina in Lights! Camera! Action!

Beals own self-determinedly queered visuals (e.g., the leather and lace at the Superdome) are themselves redoubled as queer fans manipulate images of Beals. Her body transmogrifies into a kind of assemblage as fans edit footage of Beals into scratch videos, stop video to create still images of her, or simply deploy their imaginations (and picture Holloman’s mouth somewhere south of her hands). These visuals not only redouble but then double again as Beals’ determination to queer and race Bette and to queer and race Beals ultimately queers and races her audience. William J. T. Mitchell writes, “The medium does not lie between sender and receiver; it includes and constitutes them ... Our relation to media is one of mutual and reciprocal constitution ...” (qtd. in Gorkemli). Thereby, Beals not only casts herself a queer, intersectional rhetor but queers and races (and is dialectically re/queered and re/raced by) the audience who views her.

The visual rhetoric that Beals deploys foregrounds the interdependence of rhetor and audience, of race and sexuality, her images making demands on the viewer (just as discourse has acted upon Beals). However, Beals wrestles control of the gaze, unhinging the biracial and the queer from pathology or kink. Race has always been wielded as a hegemonic mechanism to regulate sexuality and vice versa. With Beals’ insistence on “fluidity and mobility” (Craig 633), her embodied rhetoric becomes embodied resistance to the material conditions that have generated these circumstances in the first place.

Queerness, Intersectionality, and Counterworld-Making

Thus far I have outlined three rhetorical strategies that Beals appropriates to accomplish queer and intersectional ends: identification and conscious coalition with alterity, rejection of essentializing singularity in favor of intersectionality, and dialectical embodiment. Whether she dresses down a sophomoric reporter, theorizes the necessity of revising metanarratives to generate representations of and discussions about intersectionality, or recasts her own queered, intersectional body, Beals manifests a verbal, visual, and embodied rhetoric that critiques hegemony. By rejecting naïve, bumper sticker tropes (e.g., “straight, not narrow,” thereby reinstantiating the heteronormative, or “born this way,” instantiating a homonormative), Beals works toward Alexander and Rhodes’ goal of “unseat[ing] the rhetorical and material tyranny of the normal itself.”

In this section, I briefly highlight three additional rhetorical strategies that Beals employs as means of realizing her rhetorical endgame of counterworld-making. First, she recurrently turns normative metanarratives to her advantage, obliging the revolutionary to appear temporarily mundane. Michael Warner offers, “all discourse or performance addressed to a public must characterize the world in which it attempts to circulate and ... must attempt to realize that world through address” (113). Warner understands worlds as formed, furthered, and disrupted via discourse. Skilled rhetors, then, must hold shrewd grasps of these worlds, the extant and the aspirational. When Beals in her 2006 Pride address, for example, invokes love, she summons an inclusive discourse that unsettles homophobic characterizations of LGBTQ relationships, manipulating popular discourse that may be persuasive within the status quo. Alexander and Rhodes address the comprehensibility that Beals’ rhetorical move gives queer relationships:

… If queers are to have agency within the dominant public sphere, they must address how that sphere characterizes itself to itself... . [Q]ueer lives become intelligible ... only when they articulate themselves in the rhetoric of the dominant... . Agency ... becomes possible ... to the extent to which they can position themselves rhetorically as both challenging and maintaining the ... dominant culture.

Beals, as rhetor, is shifty. Her rhetoric invokes but also acts in excess of the normal. Beals’ “embodied boldness” pivots from the Linda Tripp tactic of “I’m just like you” and “intervene[s] to break silences, to launch critique” (Alexander and Rhodes). Beals thereby provides “deep questioning of normative understandings and practices of identity” that “give[s] voice to ... excluded others” (Alexander and Rhodes).

Second, Beals as rhetor strategically elicits her own hybridity.[4] For José Muñoz, many queer counterrhetorics emanate from a “hybrid self” (1). In defining the hybrid, Muñoz points to lesbian comic Marga Gomez. Muñoz describes Gomez’s comedy as, on the one hand, disidentification with distorted, homophobic stereotypes but, on the other, invocation and playful reconfiguring of these now newly desirable stereotypes. Muñoz frames this hybridity as both a survival strategy for Gomez and as a manifestation of counterrhetoric and counterworld-building: “The importance of such public … enactments of the hybrid self cannot be undervalued in relation to the formation of counterpublics that contest the hegemonic supremacy of the majoritarian public sphere” (1).

Beals manifests hybridity in part by collapsing J.L. Austin’s binary of illocutionary versus perlocutionary speech acts, crafting instead trans discourse that skates across categorization. Butler defines Austin’s distinction: “… illocutionary speech acts produce effects without any lapse of time … the saying is itself the doing” [a judge pronouncing, “I sentence you to …”], whereas “Perlocutionary acts … initiate a set of consequences” [a prosecutor beseeching, “I ask that you vote the accused guilty”] (Excitable Speech 17). In revising Austin, Butler examines hate speech and fragments the illocutionary/perlocutionary partition:

The threat ... promises a bodily act, and yet is already a bodily act, thus establishing ... the contours of the act to come. The act of threat and the threatened act are, of course, distinct, but they are related ... . Although not identical, they are both bodily acts: the threat begins the action by which the fulfillment of the threatened act might be achieved. And yet, a threat can be derailed, defused ... . (11)

If instances of hate speech (a cross-burning, a shouted homophobic slur) not only instigate consequences (triggering violent acts that follow) but are violence due to the condensed historicity inherent in the utterance (the audience’s memory of fire-bombings that have followed burning crosses, of gay-bashings that began with yelled threats)—what can we make not of uttered threat but of uttered promise or praise or hope? Already bodily acts, what acts do Beals’ performance as Bette and her performativity as Beals not only promise but instantiate in the moment they are performed? TLW characters’ attendance at the 2005 West Hollywood Pride parade and Beals’ keynote at San Francisco’s 2006 Pride “are, of course, distinct, but they are related” (Butler 11). “The [promise of Beals’ Pride attendance] prefigures ... a bodily act and yet is already a bodily act, thus establishing ... the contours of the act to come.” The act to come will not necessarily be performed by Beals but by a counterpublic that Beals helps to shape. The “act” to come might even materialize as only the expanded worldview of one isolated queer of color. It may be easy to be blasé about TLW in Soho. It’s quite another thing to watch the show from your parents’ basement in Woodbury, Tennessee. And even if the promise inculcated in that one subject’s imaginary is “derailed, defused,” it may still be considered effective at promulgating a queer, intersectional counterrhetoric that chips at a “racial heteronormativity” that “position[s] elite, White, cisgender, male, heterosexuality as the model of normativity” (Pritchard 9).

Third, to the extent that queerness is whitewashed or intersectionality is straight, Beals performs disidentification. She disidentifies, for example, not only with normative discourses of love as always already heterosexual but with sometimes-myopic discourses of queerness itself:

[D]isidentification scrambles and reconstructs the encoded message of a cultural text in a fashion that both exposes the encoded message’s universalizing and exclusionary machinations and recircuits its workings to account for, include, and empower minority identities and identifications. Thus, disidentification is a step further than cracking open the code of the majority; it proceeds to use this code as raw material for representing a disempowered politics or positionality that has been rendered unthinkable by the dominant culture. (Muñoz 31)

Beals brings intersectionality to bear, challenging queerness’s sometime monomania, when she employs disidentification to slash the mulatta tragedy. Think briefly back to that 1990 Ebony article. In her indictment of Beals, Norment concedes that, at best, perhaps Beals is simply ill: “[P]sychiatrists say that the search for racial identity can be a mentally anguishing ordeal for mixed-race individuals... . How a biracial child copes with his identity crisis often depends on ... his parents. In many cases ... the child has little, if any, contact with the Black parent. Consequently, he or she may not develop a healthy Black identity” (138). With her late introduction of the feminine pronoun, Norment summons Beals and invokes the mulatta tragedy, a trope of which Beals and TLW writers were aware.

In the episode “Loneliest Number,” for instance, Bette and Franklin (the blundering chair of her museum’s board) enter into a confrontation. When Franklin informs Bette that a potential donor is “one of your people,” Bette snaps, “One of my people? ... What, is she a Yale graduate? Is she an art history major? Is she a mulatto gal?” This episode aired on March 6, 2005. Just three months later on June 11, 2005, when accepting her GLAAD Golden Gate Award, Yale graduate Beals recounts her girlhood attempts to locate images of biracial women, sharing, “... I wasn’t aware I was supposed to be this insane, over-sexed, tragic mulatto gal” (wildchildivy). It’s difficult to know where the phrasing of mulatto gal first arose: in TLW writers’ room, in Beals’ mind, in the larger cultural consciousness that Beals and Bette tap, or in a mashup of all the above. Regardless, Beals’ invocation of and disidentification with the mulatta is not unlike Marga Gomez’s invocation of and disidentification with “truck-driving closeted diesel dykes” that Jose Muñoz describes (3). Like Gomez, both Beals and Bette leverage disidentification, here with a racist heteronormativity, finding “redemptive power in bodies that are hated and condemned” (Craig 630). As a biracial woman, Beals has always “been labeled as being outside ... acceptability and normality” (Pritchard 2). That very alterity provokes Beals to argue not for what Patricia Hill Collins calls “alternative knowledge claims” (e.g., reassuring racists that biracial women are not pathological) but for an “alternative epistemology” whereby Beals flouts “the basic process used by the powerful to legitimate their knowledge claims” (Black 219). Defying a regime of essentializing binaries with rhetoric that hinges on proliferating, interlocking resignifications, Beals generatively ruptures both straight and queer metanarratives.

Conclusion

Figure 7. L Word Fan Tweet, included in Jones

On November 23, 2017, the British “LGBT+” media service Pink News confirmed Showtime’s reboot of TLW. The resulting hullabaloo surprised no one familiar with the loyal fandom that has continued to surround the show. “Its dedicated fanbase had some intense reactions,” writer Maddie Jones deadpanned. Noting lesbian comic Carmen Esposito’s tweet “PUT ME IN COACH IM READY TO PLAY” and Roxanne Gay’s “Dear @Showtime I will be a writer on this for you,” average viewers’ reactions were the most priceless. Learning that Jennifer Beals would return, as an actor but also now an executive producer, fans gushed, “The L Word sequel? God is real, I can feel her. I’ve never felt gayer” (@bbpretty96, qtd. in Jones).

Such responses demonstrate that Jennifer Beals’ rhetoric matters—it enables us to witness intersectional, queer discourse that transpires in far-reaching, popular ways that remain imperative for her queer, intersectional audience. Beals’ counterrhetoric may have begun partly as an attempt to harness the “power to name oneself and determine the conditions under which that name is used” (Butler, Bodies 227). Yet soon enough, her discursive interventions were taken up via reception, allowing us to observe how co-constitutive construction between audience and rhetor can take place as they engage in queer, intersectional dialectic. According to Muñoz, “performance permits the spectator, often a queer [or person of color] who has been locked out of the halls of representation or rendered a static caricature there, to imagine a world where queer [and Black and Brown] lives, politics and possibilities are representable in their complexity” (1). TLW, and especially Beals’ rhetoric on and surrounding it, remain significant because intersectional and/or queer viewers continue to seek themselves in a too-often white and heteronormative social. Beals’ rhetoric enabled a dialectic in which rhetors need not be de-raced or un-sexed, thereby creating countercommunities and forging new ways to make and participate in countercultures.

While it is instructive to trace Beals’ savvy use of varied rhetorical strategies—identification and coalition with alterity, rejection of singularity and embrace of intersectionality, embodiment, manipulation of metanarrative, hybridity, and disidentification—more important is that Beals shapes these strategies to provide performances and performatives that promote counterpublics in which racist and heteronormative essentializations splinter. Beals’ rhetoric forces us to examine the privilege often imbued in constructions of both “queer” and “Black.” Jasbir Puar, for example, criticizes “normative gayness, queerness, or homosexuality,” creations that “execute a troubling affirmation of the teleological investments in … [metanarratives] that have long been critiqued for the privileged (white) gay, lesbian and queer liberal subjects they inscribe and validate” (2). Though their projects differ, relatedly, Joan Morgan argues Black female sexuality “remains comparatively under-theorized” and “stubbornly heteronormative” (38). Queer rhetorical studies could learn a lot from Puar and Morgan. And from Beals, too.

Perhaps the most important implication of Beals’ rhetoric is that, while maybe not in every rhetorical moment but far more often, intersectional queerness ought to become queer rhetoricians’ default lens of investigation. We see in Beals’ rhetoric how intersectionality can abet the early promise of queer studies. Intersectionality cracks open concepts and identities naturalized to appear singular. Not unlike early queerness’ rejection of identity politics, intersectionality’s refusal of a sole mandrel of identity helps to prevent the expansion of oppression of those already oppressed—the erasure of race within the white gay community in service to false unity claims, for example. Intersectionality refuses myths of singularity in part by insisting that identity is not static but “negotiated with other people, cultures, spaces, and values” (Chávez 22). In acknowledging the audience’s role in the discursive creation of subjects, intersectionality facilitates the very coalition-building that queer activism has advocated. Conjuring the coming of queer and intersectional politics, Audre Lorde, who refused to ignore or hierarchize her identities of woman, Black, lesbian, warrior, mother, and poet, detailed 40 years ago how “racism, sexism, and homophobia are inseparable” (“The Master’s” 110). Advocating an “interdependency,” Lorde argues, “Difference must be not merely tolerated, but seen as a fund of necessary polarities between which our creativity can spark like a dialectic” (111). Focusing on single subjectivities, then, can not only further the subjugation of those cast as minorities within minorities but oversimplify our analyses of identity, power, and culture. Employing masters’ logics, even “when they are adopted by oppressed people who attempt to challenge their oppression” (“Age, Race” 23), tragically mutes possible counterworld-making that might be forwarded.

Just as early promises of queerness were in part derailed due to its appropriation into unacknowledged (forget untheorized) whiteness, we must guard against the hazard that intersectionality’s project will be deflected into articulating increasingly micro-classifications of identity, returning us to silos of disassociated oppressions. Instead, intersectionality and queerness ought to disturb either’s stasis, and to the degree that either queerness or intersectionality is erased in rhetorical studies, we might proceed apprehensively.

Beals fashioned intersectional, queer rhetoric that acted. Like Whitman and Wilde whom Alexander and Rhodes laud, Beals was “clearly queer, in [her] investment in the homoerotic, but also in [her] insistence … of the inter-relationship between sex and politics” and, I would add, race. Beals disrupted normalizations of heterocentrism and whiteness, enabling a rhetoric which Carly S. Woods describes as “concerned with shifting webs of relationships rather than singular articulations of identity” (79). Beals’ shifty rhetoric refuses an oversimplified “purity logic” (Lugones) where she might have cast herself solely as a de-raced, straight supporter of LGBT folk. As Chávez writes, “An intersectional perspective highlights some of what gets obfuscated, collapsed, or ignored …” (29). Significantly, Beals frequently uttered intersectional rhetoric in the very spheres in which interlocking identities are often suspended: at GLAAD galas, on LGBTQ websites, and at Pride events. Beals appears as a queer and intersectional rhetor before audiences that might reject her layered, complex subjectivity and discourse. In doing so, her intersectional, queer rhetoric—like Lorde’s—moves toward queer politics’ goal of coalition-building and counterworld-making, promises of queer thinkers too often unrealized.

[1] Beals received a 2004 Mixed Media Watch Image Award for her “unwavering commitment to promoting the visibility of mixed race people,” as did TLW for “tackling difficult racial issues and portraying this mixed race family with depth” (Warn, “Radical” 196), recognition the series could hardly have garnered without Beals’ interventions.

[2] TLW’s construction of Yolanda is disturbing. A political poet, Yolanda too easily replicates the pervasive “angry Black woman” trope. Bette’s dismissal of the spelling of sistah in the title of Yolanda’s book, Sistah Stand Up, underscores the show’s indictment of Yolanda’s anger and perhaps her dark skin, too. However, turning to Beals’ history may somewhat explain Yolanda’s depiction.

[3] Surreally, not only did fictive TLW characters attend Dinah Shore, but so did the cast of Showtime’s reality series The Real L Word, also produced by Chaiken.

[4] Like Patricia Bizzell, I am uncomfortable with the term hybridity as it can suggest a melding of stable identities. I use it guardedly here, partly to invoke Muñoz’s important work.

Akass, Kim, and Janet McCabe, editors. Reading The L Word: Outing Contemporary Television. I.B. Tauris, 2006.

Alexander, Jonathan, and Jacqueline Rhodes. “Queer Rhetoric and the Pleasures of the Archive.” enculturation, no. 13, 16 Jan. 2012, http://enculturation.net/files/QueerRhetoric/queerarchive/Home.html.

Althusser, Louis. Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, Monthly Review Press, 2001.

Bizzell, Patricia. “The Intellectual Work of ‘Mixed’ Forms of Academic Discourses.” Alt/Dis: Alternative Discourses and the Academy, edited by Christopher Schroeder, Helen Fox, and Patricia Bizzell, Boynton/Cook Heinemann, 2002, pp. 1-10.

Butler, Judith. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex. Routledge, 1993.

---. Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative. Routledge, 1997.

Chávez, Karma R. “Doing Intersectionality: Power, Privilege, and Identities in Political Activist Communities.” Identity Research and Communication: Intercultural Reflections and Future Directions, edited by Nilanjana Bardhan and Mark P. Orbe, Lexington Books, 2012, pp. 21-32.

Collins, Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness and the Politics of Empowerment. Routledge, 2000.

---. “Gender, Black Feminism, and Black Political Economy.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 568, no. 1, 2000, pp. 41-53.

Craig, Collin. “Courting the Abject: A Taxonomy of Black Queer Rhetoric.” College English, vol. 79, no. 6, 2017, pp. 619-639.

Ensler, Eve. The Vagina Monologues: The Official Script for the 2008 V-Day Campaigns. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, http://web.mit.edu/dvp/Public/TVMScript2008.pdf.

Gardner, Sean. “V TO THE TENTH – V-Day 10th Anniversary Benefit Performance (Jennifer Beals).” Zimbio, 2007, http://zimbio.com/pictures/Hh44neE_Jvg/V+TENTH+V+Day+10th+Anniversary+Benefit+Performance/sklWoo7GwRv/Jennifer+Beals.

Gorkemli, Serkan. “Gender Benders, Gay Icons, and Media: Lesbian and Gay Visual Rhetoric in Turkey.” enculturation, no. 10, 18 Jan. 2011, http://enculturation.net/gender-benders.

Grubb, R.J. “Before ‘The L Word,’ TV Was What You Made It.” Bay Windows, 15 Jan. 2004. LGBT Life with Full Text.

Gunter, Kim. “Yolanda Part 1.” YouTube, 12 Sep. 2016, http://youtube.com/watch?v=xZKlcdEafa8&feature=youtu.be.

---. “Yolanda Part 2.” YouTube, 12 Sep. 2016, http://youtube.com/watch?v=lNWxYCc0xaU&feature=youtu.be.

Halberstam, Judith. In a Queer Time and Place. NYU P, 2005.

Johnson, E. Patrick, and Mae G. Henderson. “Introduction.” Black Queer Studies: A Critical Anthology, edited by Johnson, E. Patrick, and Mae G. Henderson, Duke UP, 2005, pp. 1-20.

Jones, Maddie. “The L Word Reboot Is Here and Queer Women Cannot Contain Themselves.” Pink News, 23 Nov. 2017, http://pinknews.co.uk/2017/11/23/the-l-word-reboot-is-here-and-queer-women-cannot-contain-themselves/.

Kaye, Lori. “Rose in Bloom.” The Advocate, 30 Jan. 2001, pp. 52-53.

Kennedy, Lisa. “The J Word.” Out, Jan. 2004, pp. 17-19. LGBT Life with Full Text.

Kiy, Elizabeth. “Queer Women as Sexual Beings: ‘The L Word’ and More.” Bitch Flicks, 30 May 2014, www.btchflcks.com/2014/05/queer-women-as-sexual-beings-the-l-word-and-more.html#.XWRmOHt7m71.

Kopelson, Karen. “Dis/Integrating the Gay/Queer Binary: ‘Reconstructed Identity Politics’ for a Performative Pedagogy.” College English, vol. 65, no. 1, 2002, pp. 17-35.

“Lights! Camera! Action!” The L Word, season 5, episode 6, Showtime, 10 Feb. 2008.

“Listen Up.” The L Word, season 1, episode 9, Showtime, 7 Mar. 2004.

“Loneliest Number.” The L Word, season 2, episode 3, Showtime, 6 Mar. 2005.

Lorde, Audre. “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference.” Lorde, pp. 114-123.

---. “The Master’s Tools Will Never Destroy the Master’s House.” Lorde, pp. 110-113.

---, editor. Sister Outsider, The Crossing P, 1984.

Lugones, Maria. Peregrinajes/Pilgrimages: Theorizing Coalition Against Multiple Oppressions. Rowman & Littlefield , 2003.

Morgan, Joan. “Why We Get Off: Moving Towards a Black Feminist Politics of Pleasure.” The Black Scholar, vol. 45, no. 4, 2015, pp. 36-46.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. U of Minnesota P, 1999.

Norment, Lynn. “Who’s Black and Who’s Not? New Ethnicity Raises Provocative Questions about Racial Identity.” Ebony, Mar. 1990, pp. 134-139.

Pritchard, Eric Darnell. Fashioning Lives: Black Queers and the Politics of Literacy. Southern Illinois UP, 2017.

Puar, Jasbir. Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times. Duke UP, 2007.

“Rally for Obama, Pure Club.” jennifer-beals.com, http://jennifer-beals.com/gallery/thumbnails.php?album=304.

rps75. “Jennifer Beals’ speech at SF Pride 2006.” YouTube, 3 July 2006, www.youtube.com/watch?v=pPW2gbomBC0.

Russo, Vito. The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies. Harper & Rowe, 1987.

Schenden, Laurie. “Folks Like Us.” Curve Magazine, Dec. 2002. thelword2004.tripod.com, 11 Feb. 2004, http://thelword2004.tripod.com/index/id9.html.

Sternbergh, Adam. “Back in a Flash.” New York Magazine, 10 Feb. 2005, pp. 63-64.

Stockwell, Anne. “Soul of The L Word.” The Advocate, 31 Jan. 2006, pp. 42-50. LGBT Life with Full Text.

violaky. “VDAY – To the Thent.” YouTube, 22 Apr. 2008, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cFlJugUaIXE.

Warn, Sarah. “Introduction.” Akass and McCabe, pp. 1-8.

---. “Radical Acts: Biracial Visibility and The L Word.” Akass and McCabe, pp. 189-197.

Warner, Michael. Publics and Counterpublics. Zone Books, 2002.

wildchildivy. “jennifer beals glaad awards.” YouTube, 28 Nov. 2005, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DRUFu_m_Nn4.

Winans, Amy E. “Queering Pedagogy in the English Classroom: Engaging with the Places Where Thinking Stops.” Pedagogy, vol. 6, no. 1, 2006, pp. 103-122.

Woods, Carly S. “(Im)mobile Metaphors: Toward an Intersectional Rhetorical History.” Standing in the Intersection: Feminist Voices, Feminist Practices in Communication Studies, edited by Karma R. Chávez and Cindy L. Griffin, SUNY Press, 2012, pp. 78-96.