Kathleen Blake Yancey, Florida State University

(Published November 22, 2016)

During the last ten years, the field of Rhetoric and Composition has developed a renewed interest in rhetorical delivery, with most scholars seeking to re-theorize it for use in the digital age. Jim Ridolfo and Danielle Devoss, for example, re-theorize rhetorical delivery as rhetorical velocity:

Rhetorical velocity is, simply put, a strategic approach to composing for rhetorical delivery. It is both a way of considering delivery as a rhetorical mode, aligned with an understanding of how texts work as a component of a strategy. In the inventive thinking of composing, rhetorical velocity is the strategic theorizing for how a text might be recomposed (and why it might be recomposed) by third parties, and how this recomposing may be useful or not to the short- or long-term rhetorical objectives of the rhetorician.

This re-conceptualization puts delivery in dialogue with invention—through the inventive thinking of composing—as the authors have it; such a re-conceptualization suggests that considerations of delivery function as sites of invention. Taking a similar re-theorizing tack but conceptualizing delivery more broadly, Jim Porter suggests that the range of Internet-based choices for delivery marks a new moment in composing's history:

“Internet-based communication” is, of course, not a monolithic, well-defined thing: it is a range of media, technologies, rhetorical venues, discourse genres, and distribution mechanisms—everything from online discussion forums to news outlets to academic journals to shopping malls to online museums to simulated game and lifeworld environments to wikis to blogs to social networking services (SNSs), and so on. There are considerable rhetorical differences between a wiki, a blog, an email discussion list, and an SNS—and there are considerable ethical, editorial, and political decisions involved in setting up and maintaining any of these types of forums. We need a robust theory of digital delivery to help us navigate these kinds of rhetorical complexities. Understanding how the range of digital delivery choices influences the production, design, and reception of writing is essential to the rhetorical art of writing in the digital age. (207-08)

As depicted in Porter's view, delivery highlights the kinds of rhetorical complexities that digital composing entails and that a composer considers. Moreover, what's interesting in these two examples, in part, is twofold. First, the new affordances made available in digital composing environments are identified, theorized, and exemplified, which permits a heightened awareness of the affordances in non-digital environments as well. Put another way, as rhetorical delivery is re-theorized, so too is writing. Second, and as important, what we also see is what's missing in our consideration of rhetorical delivery: that we haven't fully attended to the effects of digital delivery on how we read, an observation I arrived at quite accidentally and that provides a point of departure for my theorizing of rhetorical delivery here.

But first, the anecdotal discovery: In the spring of 2015, I taught a one-credit graduate reading course, Digital Delivery, and in the fall of 2014, as part of preparing for the class, I read the usual suspects—Ridolfo and Devoss, Porter, Collin Brooke and Ben McCorkle—and pedagogical applications of the theory like that articulated by Chanon, Garrett, and Matzke. In addition, I did some bread-crumbing on the web, where I encountered Hill’s Manual of Social and Business Forms, published initially in 1874, a visually rich vernacular rhetoric bringing writing, speaking, and the body together under the umbrella of delivery to guide those aspiring to upper middle-class status. Put more accurately, however, in the process of bread-crumbing, I encountered numerous versions of Hill's Manual, especially many electronic versions:

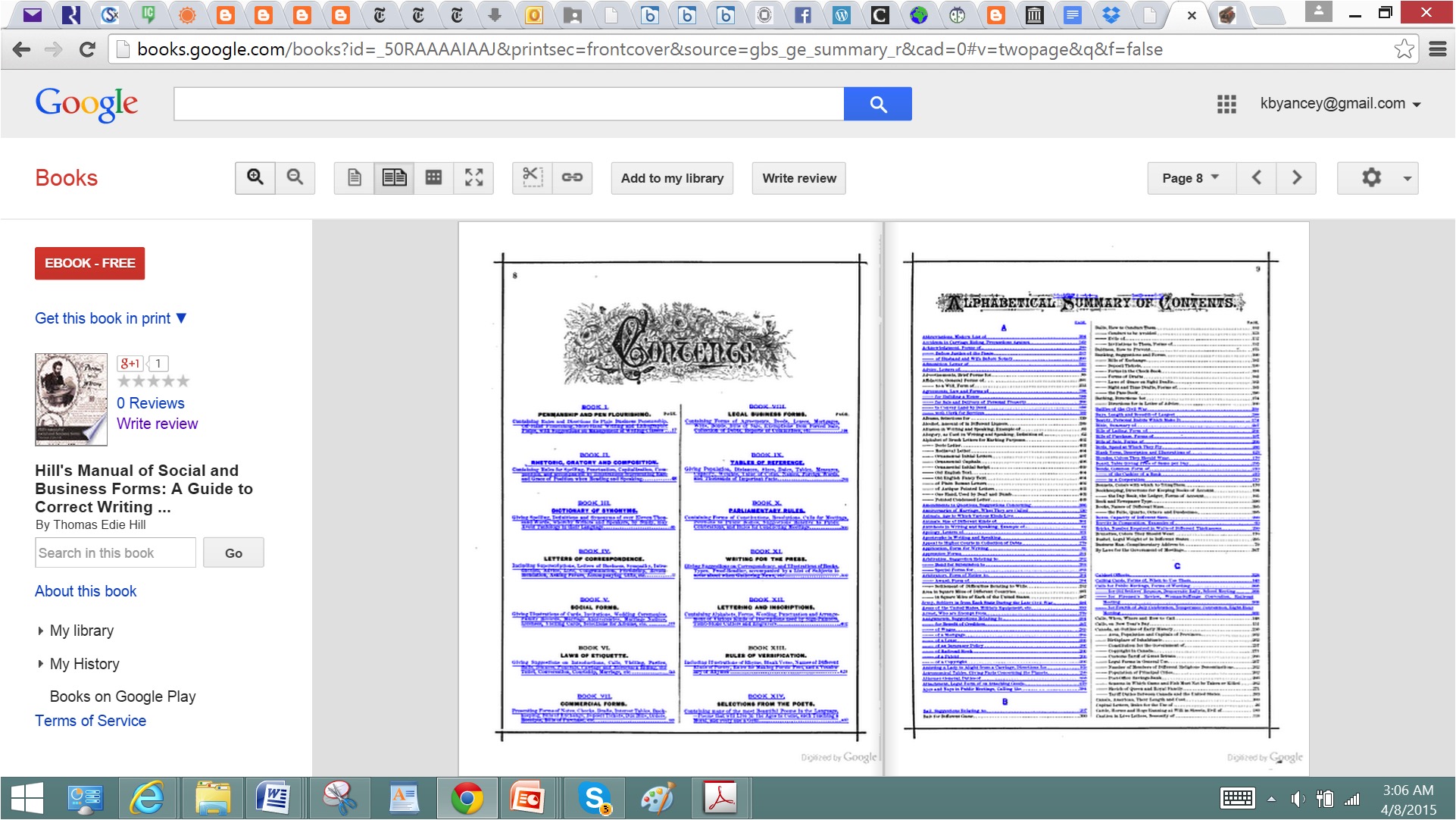

- a version hosted on Chest of Books that changes the font style from a formal serif to something resembling Comic Sans and that, as important, consistently re-arranges, or simply deletes, the many visuals enriching the print version;

- a Bancroft Library version that has all visuals and formatting deleted, with the result that this Hill's Manual is words-as-text without even layout to guide the reader; and

- a(nother) Bancroft Library version that, on first glance, appears to be a faithful, fully multimodal facsimile of one of the early print editions, but that is unexpectedly multimodal: it reads itself to me, atonally, in ways often running counter to my reading.

In other words, the rhetorical delivery(ies) of this text, I thought, raised a set of complex issues requiring articulation, at the heart of which is whether these variants or versions of Hill's Manual, these differently similar texts, are the same text (and whether that question is even important); and whether the rhetorical delivery of such texts affects how we approach them. Here, then, I re-consider rhetorical delivery oriented to (1) the texts we read; (2) the ways we read them; and (3) the issues entailed in the design of texts that are circulated on the web as well as delivered on diverse devices, ranging from the screens of workstations and laptops to those of tablets and cells. More specifically, this re-consideration includes two dimensions: the difference in such delivery as understood in digital humanities, with its focus on canonical texts and its inattention to rhetorical delivery, as contrasted with that recommended by more rhetorical approaches; and a rhetoricity introduced by the device on which the text is delivered and displayed.

In theorizing rhetorical delivery for electronic texts, it's also useful to include print. Print texts are themselves delivered, as we will see below, and they function as the original source for electronically delivered texts; to understand the delivery of electronic texts originating in print, and the ways we read them, it is instructive to begin with the source text and its delivery. In addition, when we include print texts, we can begin to develop a fuller, richer concept of delivery. As an example, consider how we treat print and digital texts: conventionally, we have assigned them to different, discreet categories: the category of print, that of the digital. But when we view them together through the same lens, we find a third category that is only available if we use that single lens: the texts in the liminal middle that exhibit a family relationship to texts in print but are distributed and circulated digitally, as in Hill's Manual. Such liminal texts, what I am calling counterpart texts, are complete or partial facsimiles of an original print version, but versions in digital form that take advantage of new affordances—for instance, as we saw above, a facsimile text including an audio recording of the same text, or a digital variant that loses features prominent in the original, like the Chest of Books' Hill's Manual, a not-quite-facsimile text re-placing, or deleting, visuals centrally placed in the original version. Moreover, counterpart texts occur on a spectrum: imitation-oriented counterparts, with fidelity to the original as the primary virtue, mark one end, and divergent counterparts, exercising a license to change the target text as its defining feature, mark the other.

To explore these issues—counterpart texts; rhetorical delivery as constituted in digital humanities and in rhetoric; rhetorical delivery and the text created through delivery; and the role that a device plays in rhetorical delivery—I begin with an early print edition of Hill's Manual of Social and Business Forms as exemplar. Published first in 1874 and important in its own right, Hill's Manual, especially when viewed through Richard Lanhan's concept of looking at and looking through, helps us understand both how rhetorical delivery was conceptualized for nineteenth-century non-academic readers and how a nineteenth-century vernacular rhetorical delivery taps the affordances of the page.1 In so doing, Hill's delivers a good deal more than lessons in delivery. In addition, in analyzing Hill's Manual for its account of delivery, we set the stage for defining counterpart texts, for raising questions about how rhetorical delivery enacts differentiated texts, and for beginning to theorize such texts and their delivery.

In 1878, Thomas E. Hill—a teacher, a newspaper publisher, and a mayor of both Aurora and Glen Ellyn, Illinois—published the first edition of his Hill's Manual of Social and Business Forms: A Guide to Correct Writing. Available only by subscription, it defined writing capaciously and materially, its multiple genres ranging from business letters and letters of application to wedding announcements and tombstone epitaphs, and its advice on how to write well including lessons both on how to compose cursive in the Spenserian script popular at the time and on how to design writing by choosing the nineteenth-century equivalent of font size and style, what Hill called "pen and paper flourishing" and "engraver's inscriptions" (295, p). 2 Hill's Manual is thus about a good deal more than rhetorical delivery, but it is about that as well, and although published over a century ago, it has much to teach us. Here I focus on four of those lessons:

First, rhetorical delivery, at least in the nineteenth-century United States, is interestingly multimodal, bringing together writing and speech, embodiment and the visual, in a practice of delivery.

Second, Hill's lessons on delivery are themselves delivered, in part, through ornate visuals: on the pages of Hill's Manual, writing is literally, concurrently defined and illustrated as a visual practice, a point that becomes very clear when in digital versions, the line drawings are reduced, altered, or eliminated altogether. Third, Hill's lessons on delivery deliver much more than rhetorical delivery: even in focusing on delivery, they deliver other content. The content I'll focus on by way of example is twofold: the role of women and the nature of an aspirational life.

Fourth, Hill's lessons in the Manual are now distributed and circulated digitally: available in many different versions, Hill's multiple Manuals raise questions about the intersection of form, meaning, and reading; about relationships a given text has to forms of delivery and devices of display; about how we read these differently similar texts; and whether it matters that they aren't the same.

∞

Lesson One: Multimodal Rhetorical Delivery in the United States in the Nineteenth Century

The nineteenth-century rhetorical delivery encouraged in Hill's Manual of Social and Business Forms anticipates a twenty-first-century embodied electronic delivery incorporating many kinds of materiality. Hill's model was not distributed into separate domains of speech or writing, of posture or gesture; rather, Hill's rhetorical delivery collected together and employed speech, writing, and the body acting as ensemble. To be sure, delivery as it has been conventionally understood is part of the lesson. Hill advises, for example, that "To be effective, the speaker must exhibit variety in gesture, tone of voice, and method of illustration" (56, p), which is the kind of recommendation in elocution rhetorical history narrates. But even here, there is more than we might expect; in fact, Hill presents us with a vernacular physics of delivery. Pitch, Hill tells us, "represents the proper elevation of the voice . . . its use . . . to regulate the tone of the discourse to its character. If not regarded as it should be, the delivery becomes faulty and disagreeable" (451, e). Moreover, we should "Pitch the tone of voice no higher than is necessary to reach the ears of the person farthest from you in the audience, but be sure that it reaches its limit without losing its distinctness" (451, e). Also important, Hill says, is force, which "applies to the energy which is given to certain words and phrases as expressive of the earnestness with which they should be received. It is 'mental emphasis,' laying stress, in degrees, upon whatever is uttered" (451, e). We are aided by an Anglo-Saxon tongue, "filled with short, expressive words of one or two syllables, that point a sentence with wit and eloquence better than a flow of dissyllables" (451, e). But oratory, he says, isn't merely pitch, volume, force, and expressive words: oratory, as he defines it, is fully embodied, "express[ing] in the features, the position of the body, and the movements of the head and limbs, the emotions which govern the utterances of the speaker" (451, e).

As important, or at least as interesting, is the relationship Hill's Manual posits between writing and speaking, with the latter developing from the former. Inside school, "during the week, the student should declaim, the declamation being generally the student's own composition. Thus youths become acquainted to the speaking of their own thoughts correctly, and oftentimes eloquently" (56, p). We might expect to see declamation in school, but even for those out of school a kind of declamation is advised, as Hill adapts his recommendation to suggest something of an extracurricular exercise:

Let a debating club be established of half a dozen or more persons, to meet regularly during the week, at stated times, for the discussion of current topics of the day, either at a private residence, some hall chosen for the purpose, or at a schoolroom, the exercises of the occasion being interspersed with essays by members of the club, the whole to be criticized by critics appointed. (56, p)

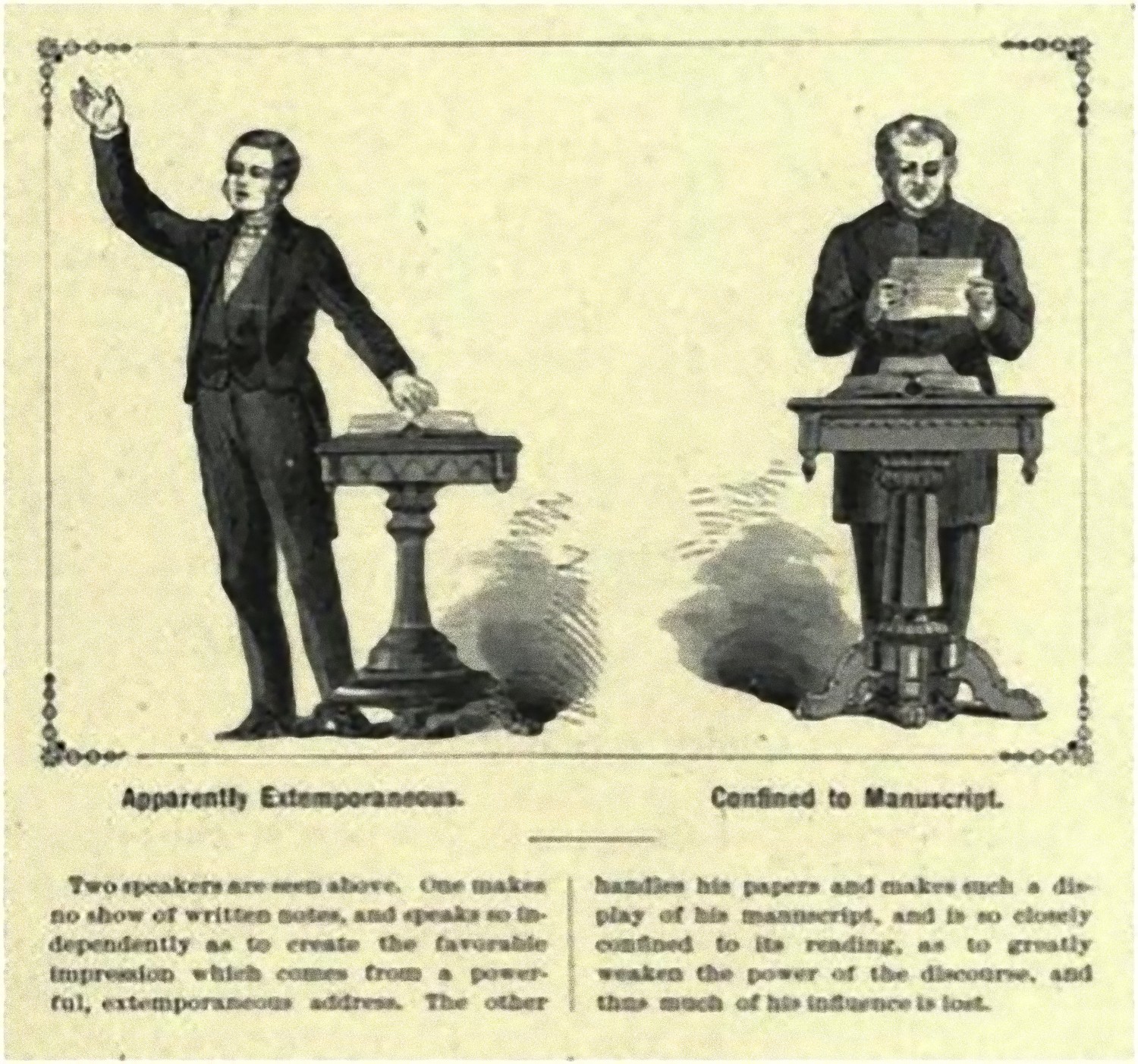

In sum, speaking begins with writing; to have something to say, one might read; but when one speaks, it's important not to read but rather to deliver the talk as though it is extemporaneous. In sum, rhetorical delivery in Hill's Manual is embodied and multimodal, a process incorporating writing, reading, speaking, and gesturing.

Lesson Two: The Depiction of Writing as a Visual Practice

Hill's Manual, however, delivers more than lessons in rhetorical delivery. The Manual is richly, classically visual, that visual performing its own delivery of an upper class elegance assuring readers of the value of Hill's advice through layout, titles, images, typefaces, graphics, and lettering collectively reminiscent of a medieval manuscript. Indeed, it's worth noting the difference in the visuals defining delivery in Hill's Manual and the absence of those in the more scholarly oriented Adam Sherman Hill's The Foundations of Rhetoric. In T. Hill's Manual, images carry the point home, as in the case of "Apparently Extemporaneous" delivery and "Confined to a Manuscript" delivery.

The extemporaneous man is, as the image portrays, younger and good looking, the man tethered to the manuscript older, less attractive, and downcast. Although the instructions for how to deliver are useful, the visuals tell their own story, one paralleling the verbal directions, and in so doing invite a kind of Burkean identification with the extemporaneous, energetic man. Who wants to be confined—in word or image? Likewise, the pages invite a Lanham-like reading: we look both AT them for instruction and THROUGH them for articulation of how they mean.

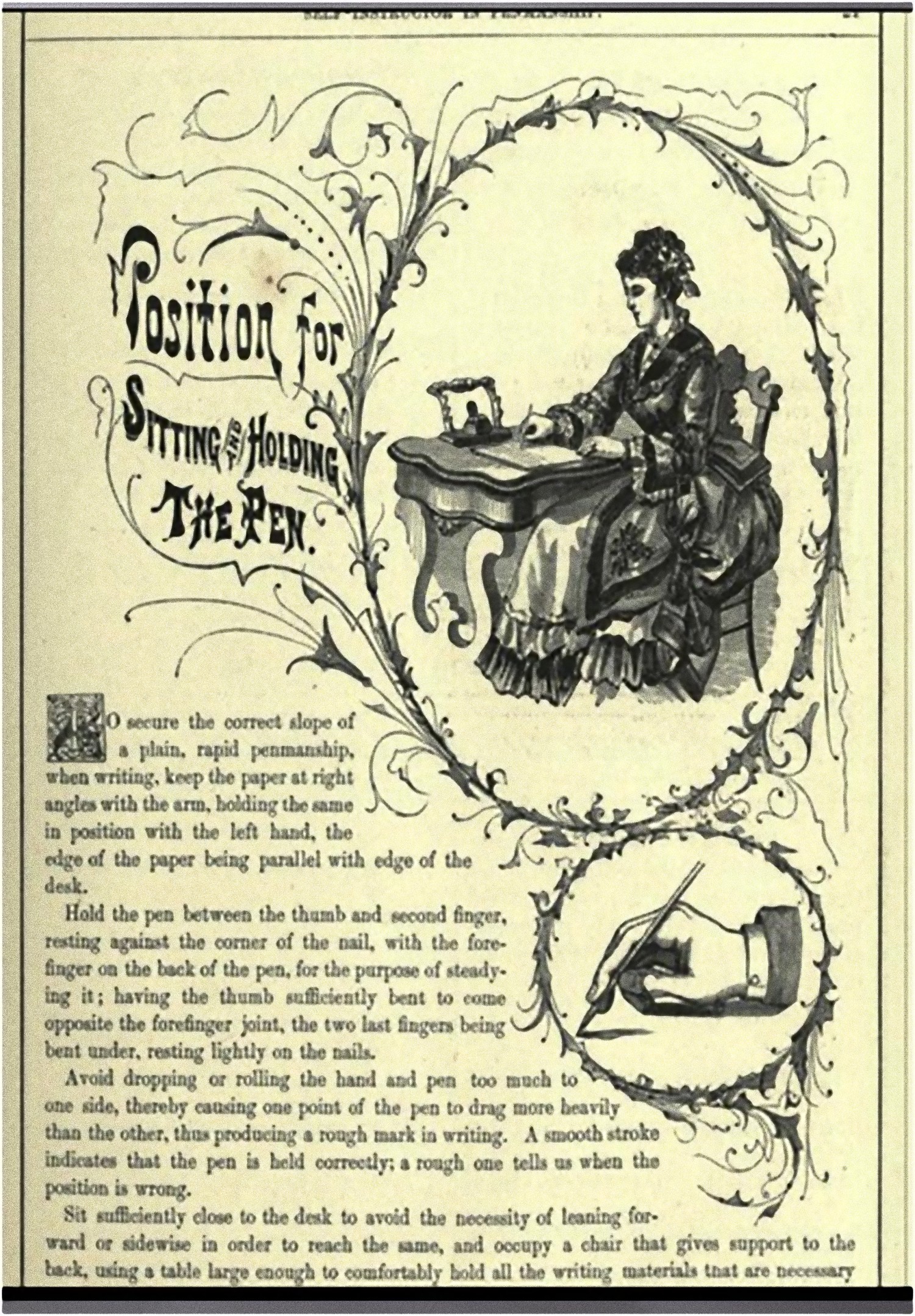

Hill's instructions for how we should position ourselves while writing provide another example of how visuals deliver. Here, Hill's language describes precisely how we should sit, where our backs should rest, and how our materials should be arranged. "Sit sufficiently close to the desk," he tells us, "to avoid the necessity of leaning forward . . . and occupy a chair that gives support to the back, using a table large enough to comfortably hold all the writing materials that are necessary" (21, e). The visual shows us how to do this, and the woman writing at the desk is postured as Hill describes, but she is no ordinary woman: the desk is fine, the back of the chair ornate, the woman herself wearing a tailored dress with a shawl flowing over the skirt cascading into two rows of ruffles, her hair dressed as finely as her body.

And the frame itself—with the image of the writing encircled in a kind of portrait oval, suggesting the kind of portrait suitable for framing in an upper middle class parlor, adjacent to the title of the lesson, "Position for Sitting and Holding the Pen"—consumes not only over half the page but also the entire top half of the page, with the language confined to the bottom half. As we literally see, delivery here has a decidedly visual cast.

Lesson Three: What Delivery Delivers—Instruction and a Different Content

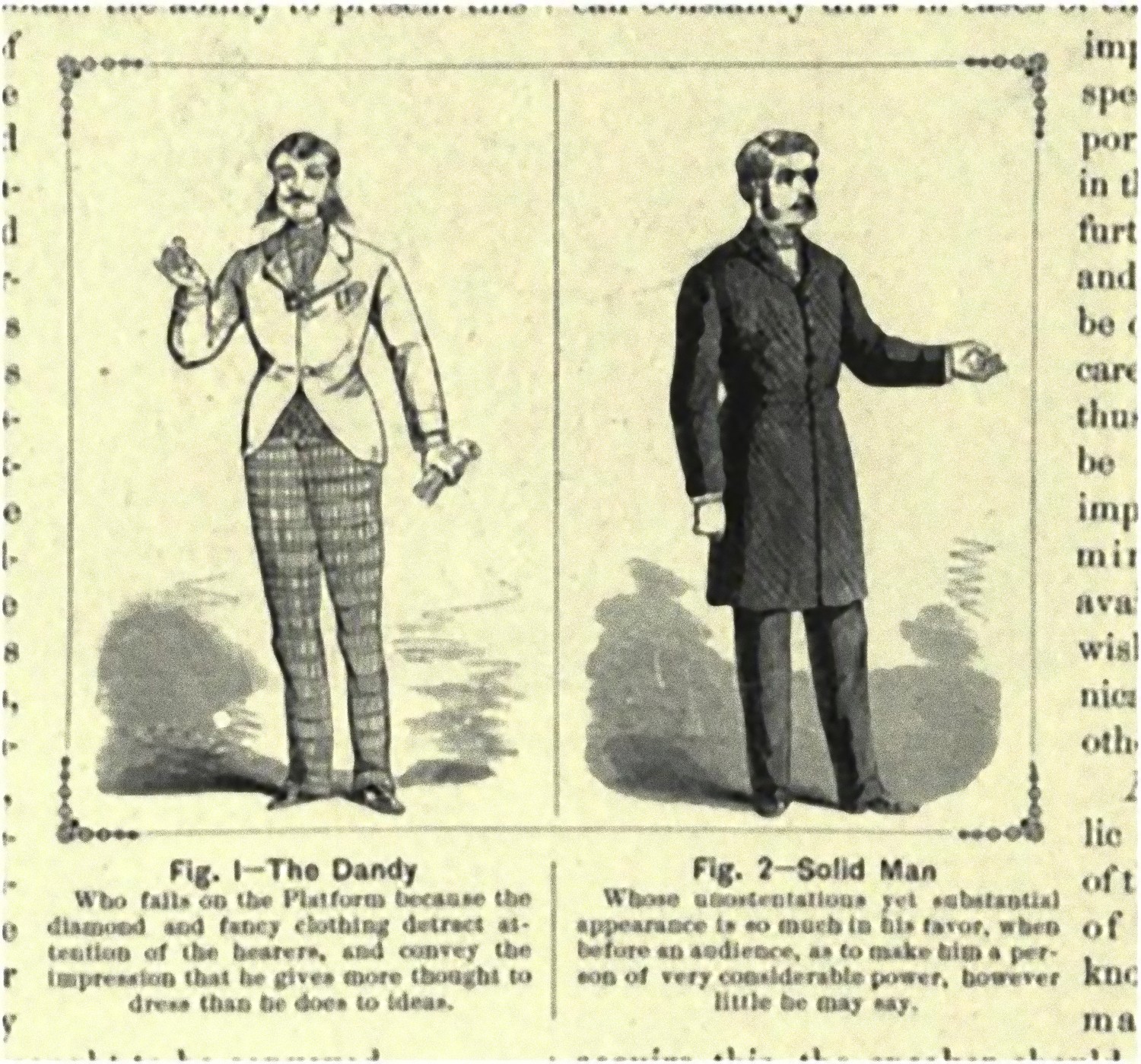

What Hill's Manual is delivering is considerably more than delivery, in part because it is a hybrid genre—part manual, part book of etiquette, part encyclopedia. Put as a proposition: Hill's Manual, though ostensibly about Social and Business Forms, delivers another content, principally about the decorum characterizing upper class life and ways that readers adopting such practices can replicate this behavior, at the least, or use these practices to become one of the upper classes, at best. Such an analysis demonstrates that rhetorical delivery—like instruction about writing, like school itself—is never transparent: it always delivers multiple content and in multiple ways. Thus, in outlining aids to public speaking, Hill's contrasts “the dandy" with "the solid man," again in a visual dominating the page. In words, the dandy, who "conveys the impression that he gives more thought to dress than he does to ideas" is the poster child for what one doesn't want to be—speaking in public or anywhere else—a point that is underscored in the description of the solid man, "whose ostentatious yet substantial appearance is so much in his favor when before an audience as to make him a person of very considerable power, however little he may say" (446, e). To deliver, as language and image working together suggest, the solid man simply needs to be.

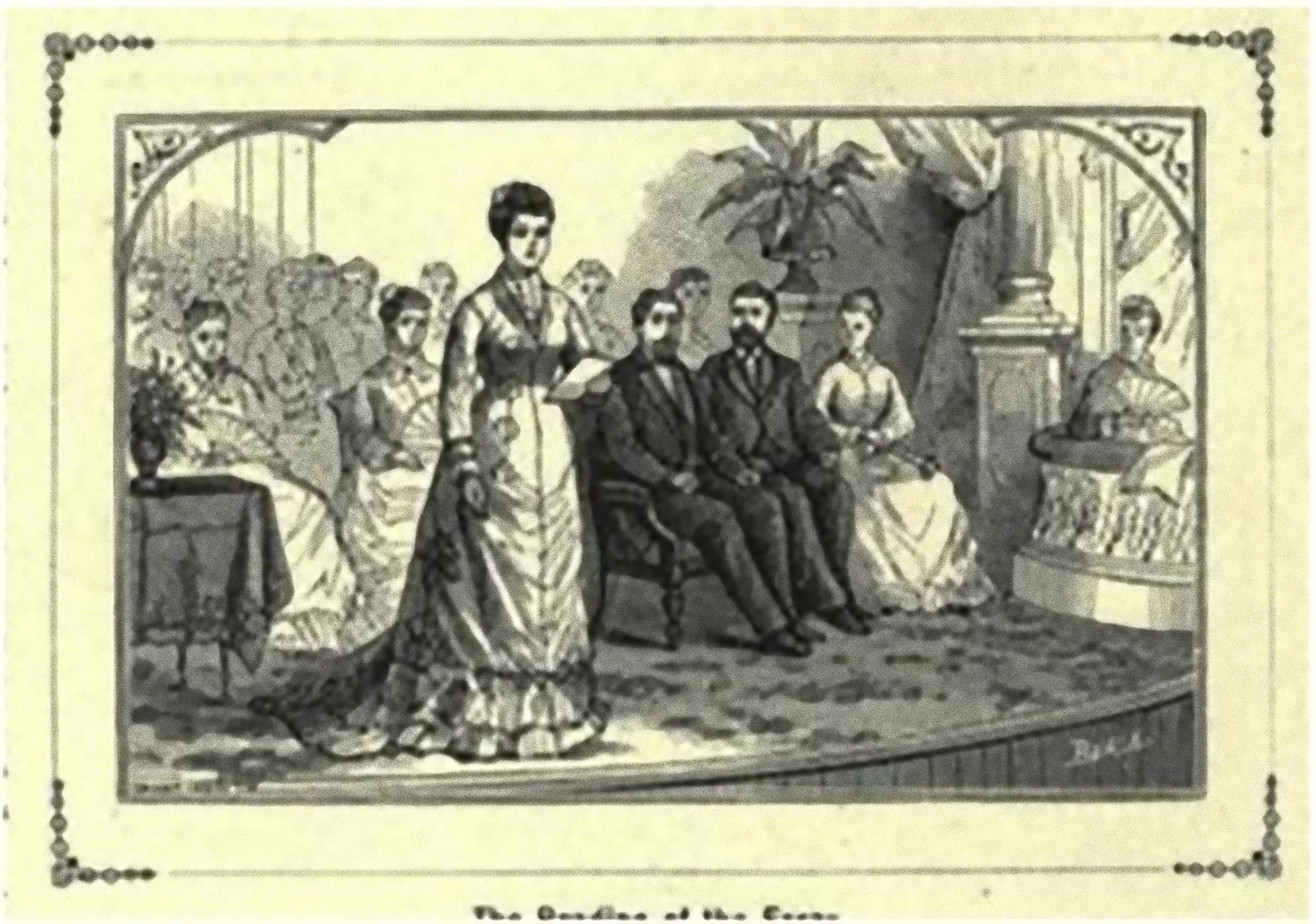

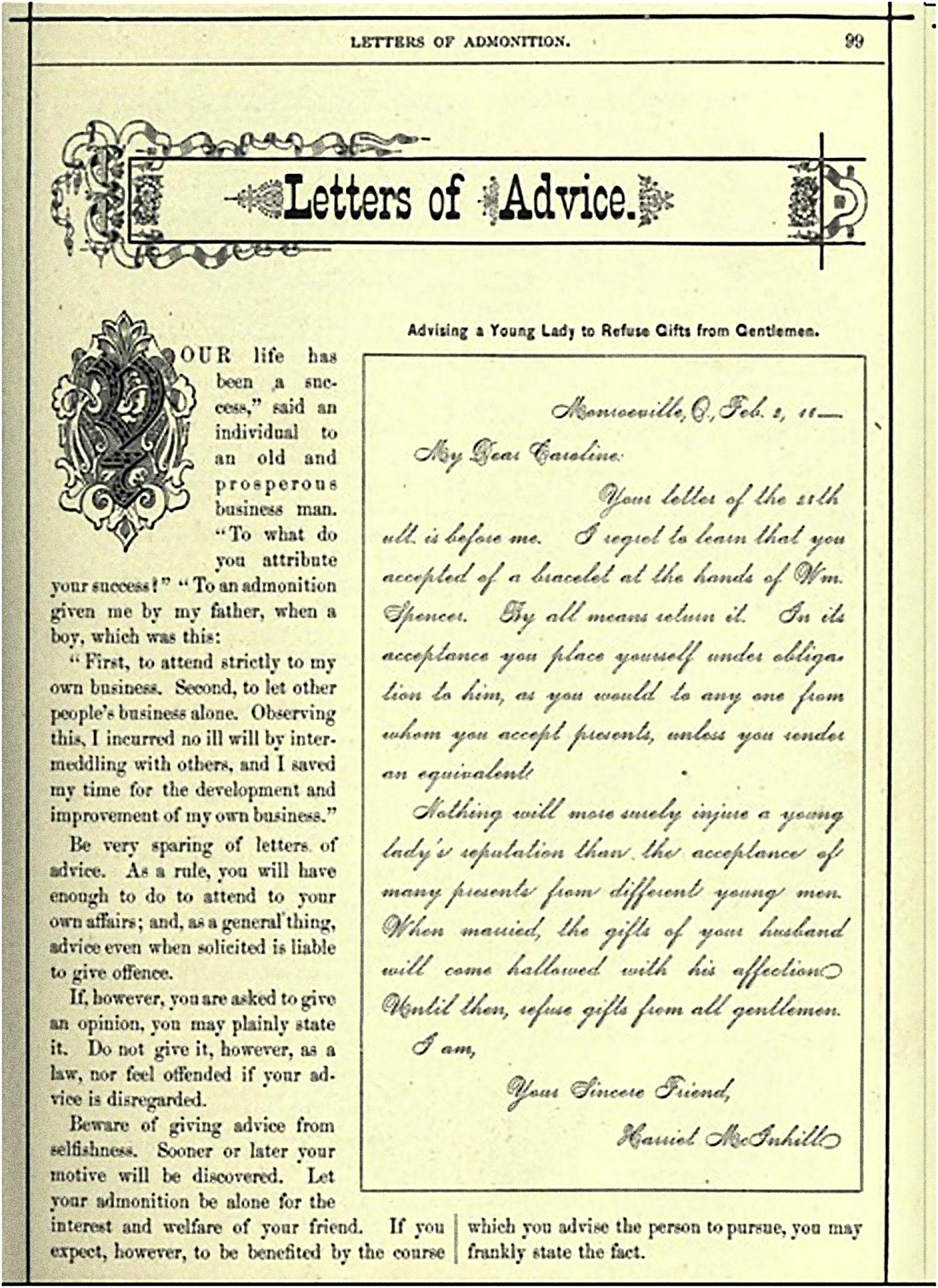

We see similar lessons in the examples Hill's provides, examples that are not innocent or neutral but rather directive if inconsistent. For instance, as we see in the visual and in the language describing effective delivery, women too can deliver, no small thing in the nineteenth-century United States. But most of the content is less progressive, more prescriptive, collectively portraying a very gendered upper middle-class behavior and thus encouraging readers to behave similarly. There are parties and receptions requiring ornate invitations, family records to properly maintain. Such records, we learn, are especially helpful when there are "claims to pensions or heirship to estates" (128, e). When writing letters of advice, we can consult Hill's model letters, which remind us to beware of bad company; to avoid a hurried marriage—but apparently only if you're a young man and to maintain health by developing good habits and regularity of habits, especially when it comes to sleep, dress, cleanliness, "inflation of the lungs," diet, exercise, and condition of the mind. Women are included, though minimally: the singular model letter of advice addressing women encourages them to "refuse gifts from all gentleman" because with patience on their part, such gifts will—presumably—be delivered by a husband "with his hallowed affection" (101, p). And so too the lesson on conveying congratulations: the two women receiving congratulations in the model letters have completed school and gotten married, respectively, while the men have collectively been promoted to school superintendent, fathered a son (not a daughter), and received a legacy. In other words, the lesson on how to write letters of advice, like the lesson on congratulatory letters, is at least as much a lesson on how to live a certain kind of gendered life depicted under the guise of providing rhetorical help—a masculine, upper middle class, professionally and personally successful life.

Lesson Four: What Hath Electronic Delivery Wrought? 3

In contrast to its availability through subscription in the nineteenth century, Hill's Manual of Social and Business Forms, in original print and in digitized reproductions, in whole and in parts, is today distributed and circulated widely. Many editions of Hill's can be purchased on eBay; can be viewed in diverse formats in the Internet Archive; can be accessed on other free sites like Chest of Books; can be purchased in original print, reproduced print, and electronic book form on Amazon and other bookselling sites; and can be viewed in fragments disassembled from the book and re-assembled by others on their own websites. In moving from subscription to distribution and circulation, Hill's Manual illustrates a myriad of possibilities for a rhetorical delivery facilitated by digital technologies as it also raises questions about how we treat such texts, about the material differences among them, about the content(s) they deliver, and, not least, about how we read these differently similar texts.

To explore what this means, it's useful to look at three digital versions of Hill's Manual of Social and Business Forms. A first version is hosted at the Internet Archive, and the first observation about it that we might make is twofold: (1) it opens with a facsimile of the book cover, and (2) at first glance, the pages seem almost perfect imitations of the original pages. In that sense, the cover and the pages resonate with the original—which might or might not be important.

- Is such resonance important?

A second observation is that the affordances of this facsimile version of Hill's Manual widen reading options considerably. No longer confined to a single means of accessing the text—moving pages forward or backward by finger-touch—we can engage this counterpart text in any number of ways via multiple formats, from a standard PDF to a Kindle version, though each of these is its own counterpart text. If we're using the PDF version, for example, we need to have solid bandwidth because the download isn't microwave quick; if we are using the Kindle version, we should be prepared to give up the visuals. Suppose that we use the Internet Archive version with its several affordances: we can simply read; we can enlarge pages or shrink them; we can search inside the text. As important, the interface itself offers us a Lanham-like experience. What Lanham claimed is that computers enhance the capacity to create and deploy texts in which "the textual surface has become permanently bi-stable. We are always looking first AT it and then THROUGH it, and this oscillation creates a different implied ideal of decorum, both stylistic and behavioral. Look THROUGH a text and you are in the familiar world of the Newtonian interlude . . . . Look AT a text, however, and we have deconstructed the Newtonian world" (5).4 Such oscillation characterizes the first text offered by this interface, but there is a second, a plain text, that refuses such oscillation; opt for the plain text, and that's exactly what we get.

- Does that matter?

Alternatively, we might return to the earlier interface and try another button allowing the reading to become oral: we read along with a computer-modulated a-tonal and a-inflected voice. Such a reading may not be intuitive, but it accomplishes several objectives: it provides access; it changes—and some might say enlarges—the reading experience; it revises Lanham so that we are looking at/looking through/listening to. Reaching such objectives of course assumes that I can access the sound on the device I'm using—another element in delivery, the device (about which, more below). Now suppose that I'm "reading" Hill's Manual—and I have reading in quotes because I'm not sure that reading describes my engagement—and linking not with mouse or keyboard but with my finger on a touchscreen so that there is a more direct tactile element: in this situation, I become a secondary agent of the text's delivery.

- How does this delivery shape our reception of the text, and does it matter? Is a more immersive reading experience, created with sight, touch, and sound, a more persuasive experience? Is that persuasion lessened given the nature of the automated voice? Does such reading transform the reading experience into a disruptive one?

A second example: the digitized version available on Google. This Hill's Manual of Social and Business Forms is easy to access, but because of the arhetorically visual nature of the text—that is, its monochromatic color, its blue linking, its badly scanned pages—its Googlized text interface overwrites the scanned text. "Looking at" for this Hill's Manual seems very at odds with the looking at prompted in both the original text and the Internet Archive facsimile. And that's before we get to the clunkiness of the navigation, which makes reading a fairly arduous task.

- Does it matter that in this delivery, the looking is very different and that the relationship between looking at and looking through is distorted?

We can consider a third example, the Chest of books version, which is also easy to access but offers a Hill's Manual that is different yet again, in part because of additions of different kinds, in part because of deletions, and in part because of re-arrangements. Surrounded by a variant of Edward Tufte's chart junk, this Hill's Manual is surprisingly linear and word-centric: not quite print uploaded but close (Yancey). Each entry is fronted with a brief synopsis and citation, making it obvious that this version has diverged from the original. This version does include some visuals from the original text, but it also re-arranges them for us, re-placing images that were side by side into a vertical placement, or removing all the images to the very end of the entry, almost as though not to interrupt our reading. Moreover, when we look at the way pages appear, we see more to distinguish variants. For example, the letters of advice in the Internet Archive, following the print text and as explained above, feature layers of visuals with different functions: here the visuals have been all but eliminated; the new font, which seems a cousin of Comic Sans, doesn't suggest elegance; and layout too has been nearly erased so that the letters run into each other. An addition to the text is a set of links taking the reader to surprising places inside Hill's—in one case, to an explanation of letters, in another to information about resorts. In that sense, reading this Hill's is like reading a text with links functioning as annotations: it's a text of someone else's reading.

- Does the inclusion of images matter? Does their placement? Do we create one meaning with clicking and another with scrolling? How important is a consistent visual aesthetic? Do we find the links others have planted for us an annoyance or an opportunity to read differently and more richly?

These questions about rhetorical delivery of in the twenty-first century, in other words, are multifold. They are partly a question about interfaces, partly a question about contexts, partly a question about affordances, partly a question about access, and partly about the role of a Kressian multimodality in the making of meaning. Put as a list of successive questions, they include:

- Is there a text in these deliveries?

- Are these three texts—and the original–the same Hill's Manual? Or are they adaptations? Or translations? Or versions? (Or are such questions simply an exercise in nostalgia?) Does it matter that when we talk about a given text, we might not be aware that we had read variants of the text, which might explain the why of how we read?

- If the visual is part of the text, does inclusion of the visuals matter? Does their placement?

- And given the role of content, what is being delivered? And what are the implications for composition? For rhetorical velocity? For the assemblage and remixing of texts?

Counterpart Texts Redux

My theory, as outlined early in this text and as demonstrated above, is that we have a set of texts requiring a new theory of rhetorical delivery. To date, we have conceptualized texts in two categories: in print or in digital. But as documented here, there is a third category: the texts in the liminal middle that have a family relationship to texts in print but that are distributed, and sometimes circulated, digitally. Because of their relationship to their print cousins, these texts are what I am calling counterpart texts.

The spectrum of counterpart texts is wide. On the one hand, we have imitation counterparts like the Internet Archive version; their appeal, in part, is that they are facsimile texts nearly identical to the print original. At the same time, given the multiple ways that such texts can be displayed and accessed, here including a version that we read differing from the version that reads the text to us, any given imitation counterpart text isn't itself necessarily a single text. In this case, the text is more a portal into a set of imitation counterparts of (what we think of as) the same text, but which are different texts both in the reading experience they offer and in the reading practices readers engage in. On the other hand, we have divergent counterpart texts whose lack of resemblance to the original is immediately obvious. In the case of the Chest of Books version of Hill's Manual of Social and Business Forms, as we have seen, images from the original are sometimes reduced, other times re-placed; the visual design that is a major component of the rhetorical delivery of the print text is nearly eliminated; and the text hosted by the Chest of Books site includes annotating links inside the text, electronic bread crumbs to someone else's reading but unaccompanied by a logic explaining it.

Rhetorical delivery of these liminal counterpart texts raises a set of complex issues; such delivery thus constitutes an exigence for a re-consideration of rhetorical delivery. This re-consideration includes two dimensions, at least: first, the difference in such delivery as understood in digital humanities as contrasted with rhetorical approaches; and second, the rhetoricity introduced by the device on which the text is displayed and which readers use to read with.

In Digital Humanities (DH), as Todd Presner explains, early work focused on digitizing texts such that the electronic texts mirrored the original print texts as closely as possible:

Just as early codices mirrored oratorical practices, print initially mirrored the practices of high medieval manuscript culture, and film mirrored the techniques of theater, the digital first wave replicated the world of scholarly communications that print gradually codified over the course of five centuries: a world where textuality was primary and visuality and sound were secondary (and subordinated to text), even as it vastly accelerated the search and retrieval of documents, enhanced access, and altered mental habits . . . .

More recently, however, DH has encouraged copies, seeing in them a kind of abundance unavailable in the single copy: the copy, according to Presner, "implies the multi‐purposing and multiple channeling of humanistic knowledge: no channel excludes the other. Its economy is abundance based, not one based upon scarcity. It values the COPY more highly than the ORIGINAL. It restores to the word COPY its original meaning: abundance.” Copies, of course, open the door to difference and remix. At the same time, Digital Humanities is also interested in maintaining "the scholarly value of the digitized resource," as this ad for a DH position makes clear:

The study of this Experienced Researcher project aims to critically explore the range of measures and methods for establishing trustworthiness, quality parameters and authenticity of digital reproductions in libraries and archives, particularly by looking at cases where levels and measures are negotiated between such memory institutions and external agents hired to perform parts of the process. The results of such negotiations might have significant bearing on the value of the digitized resource, and the level of post-processing work, use and re-use that can be performed with the digitized material within digital edition projects and other scholarly work. How and to what extent are these measures and methods maintained consistently throughout projects versus being renegotiated, possibly affecting the scholarly value of the digitized resource?

The focus here is on the text itself in the context of traditional literary concerns—the role of editions, for example, here remediated into digital editions.

By way of contrast, rhetorical studies includes digital texts as well, but taking a different focus, engages three other questions:

- What are the kinds of digital texts that are created, by scholars and others, especially texts that claim fidelity to what we might call the same origin text? Here I have created a schema accounting for such texts and showing their range, but the source material for the schema is a single text. Given a wider set of resources, are there other kinds of digital texts, and if so, what are their characteristics; do they fit into this schema, or do we need another?

- How do readers make use of these texts? For example, do readers choose different digital versions to accommodate different purposes? Or to meet different needs, such as access—as a general matter, or access given a unique situation (e.g., a loss of electricity)? Do readers have preferences for one kind of digital text, and if so why? Or perhaps different kinds of readers have different kinds of preferences?

- What rhetorical effects does each text exert? As demonstrated above, the different digital versions have different affordances; such affordances support rhetorical effects. What meaning do we make of the Hill's Manual if the visuals are stripped away or re-placed, especially when we don't know what the origin text looked like? Is it reasonable to think that we can comment on this text as a version of Hill's when the visual that so animates the origin text is absent? Put as a very specific question by way of example, is the solid man as solid without the image?

I'm on the smart phone right now and it [Hill's Manual] does have a nice mobile interface—but voiced reading doesn't appear to be part of it.

I could be missing it, or it could be a functionality specific to non-mobile devices?

Matt Davis

A second dimension of rhetorical delivery is the role that the device hosting the text plays in our meaning-making practices. In print texts, short of a misprint, the text displays the same way for every reading—until, of course, it is annotated. In digital texts, the agent of delivery isn't a page, but rather a device that determines the text that we read and can permit full access to the digital version, or not. As Jacob Craig, Matt Davis, Michael Spooner, and I explain elsewhere:

The ways texts are displayed is also, increasingly, related to what we read given that what we read is related to how we read. In 1993, for example, Bernhardt could confidently assert that "readers become participants, control outcomes, and shape the text itself" (154), but given the proliferation of reading devices, from smart phones and tablets to e-readers, laptop computers and notebooks, such a claim is much less accurate. Not infrequently, devices themselves now cooperate with or even substitute for the reader in controlling outcomes. In some cases, the device and reader work together, as when a reader adjusts the size of letters on an e-reader, for example, itself a different material practice than reading in print, one that seems very helpful. In other cases, the digital text has been "optimized" for the device, and the device itself determines what the page will be.

In other words, two factors related to device and display are important here for rhetorical delivery: the rhetorical effects of the device versus the rhetoricity of the device itself.

Rhetorical Delivery and Counterpart Texts

As both concept and practice, rhetorical delivery in the late-nineteenth, twentieth, and early-twenty-first centuries has widened considerably, as documented in Hill's Manual of Social and Business Forms, both the origin text and its multiple variants. Hill's Manual demonstrates, first, that the rhetorical delivery of the nineteenth-century everyday person in the United States, especially one aspiring to an upper-class life, was advised to be fully multimodal and embodied, bringing together print, speech, the visual, and the body. And because this theory of rhetorical delivery is itself so fully delivered in the pages of Hill's Manual, it, second, provides a telling example of what digital texts are delivering in the twenty-first century, especially when they re-deliver an historical text intended for print. Put another way, Hill's Manual of Social and Business Forms, because of its multiple digital variants, helps us understand the range of possible counterpart texts, some intended as a faithful facsimile, and others re-formatting, de-visualizing, re-assembling, and vocalizing the origin text. As students of rhetoric, we thus have new tasks before us, among them documenting the rhetorical effects of counterpart texts.

- 1. Though beyond the scope of the argument here, it's worthwhile to consider how multimodality does not inform the more academic, contemporaneous rhetoric of the time, Adam Sherman Hill's Principles of Rhetoric and Their Application, and also thus how the rhetorical delivery of counterpart texts in this case is less an issue of concern.

- 2. For a fuller account of Hill's notion of delivery, I call on two editions, one in print published in 1880, the second published in print in 1888 and available online. I have marked each citation with either a p for the print 1880 edition or an e for the 1888 version online. The considerable number of editions of Hill's, in addition to the numerous ways each is delivered, adds another layer of complexity to the issues discussed here.

- 3. In this header, readers will no doubt hear echoes of the first telegraph message between Washington, DC, and Baltimore: "What hath God wrought?"

- 4. As indicated above, it's also worth noting that Lanham's schema of looking AT and looking THROUGH applies to the print version of Hill's Manual, a potential made manifest by the detailed visuals, although given the similarities between digital editions of the Manual, the oscillation in the print editions is much more stable.

Adsanatham, Chanon, Bre Garrett, and Aurora Matzke. "Re-Inventing Digital Delivery for Multimodal Composing: A Theory and Heuristic for Composition Pedagogy." Computers and Composition, vol. 30, 2013, pp. 315–331.

Bernhardt, Stephen. “The Shape of Text to Come: The Texture of Print on Screens.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 44, no. 2, 1993, pp. 151-175.

Brook, Collin. Lingua Fracta: Toward a Rhetoric of New Media. Hampton Press, 2009.

Hill's Manual of Social and Business Forms: A Guide to Correct Writing. Moses Warren & Co., 1880. By Subscription.

Hill's Manual of Social and Business Forms: A Guide to Correct Writing. Moses Warren & Co, 1888. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/manualofsochills00hillrich.

Hill's Manual of Social and Business Forms: A Guide to Correct Writing. Chest of books. http://chestofbooks.com/business/reference/Social-Business-Forms/

Kress, Gunther Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. Routledge, 2010.

Lanham, Richard. The Electronic Word: Democracy, Technology, and the Arts. U of Chicago P, 1993.

Porter, James E.. “Recovering Delivery for Digital Rhetoric.” Computers & Composition, vol. 26, 2009, pp. 207-224.

Ridolfo, Jim and Danielle Devoss. "Composing for Recomposition: Rhetorical Velocity andDelivery." Kairos, vol. 13, no. 2, 2009. http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/13.2/topoi/ridolfo_devoss/intro.html

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. “Postmodernism, Palimpsest, and Portfolios: Theoretical Issues in the Representation of Student Work.” College Composition and Communication, June 2004, pp. 738-62.

-----, Jacob Craig, Matt Davis, and Michael Spooner. "Device. Display. Read: The Design of Reading and Writing and the Difference Display Makes." What Is College-Level Reading?, edited by Patrick Sullivan, Howard Tinberg, and Sheridan Blau. Forthcoming NCTE 2017.