Julie Collins Bates, Millikin University

(Published November 10, 2020)

The story of environmental injustice and environmental racism in the United States is a long, complex one that has been occurring for centuries. It began in the moment in which colonization of the Americas occurred and has continued, in myriad forms, since then. This long history is important to acknowledge because, as Kathryn Yusoff states in A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None, “The Anthropocene might seem to offer a dystopic future that laments the end of the world, but imperialism and ongoing (settler) colonialisms have been ending worlds for as long as they have been in existence” (xiii). The contemporary environmental justice movement in the United States originated in response to this ongoing colonialism, combining tenets of social justice with an emphasis on how people of color in particular suffer disproportionately from exposure to toxic pollutants and environmental health problems at the same time they often are ignored during decision-making processes that affect their communities (Dickinson).

Environmental justice groups often work apart from mainstream environmental organizations, which mostly comprise white, middle- and upper-class members and have faced charges of racism, classism, and insensitivity to cultural groups (Pezzullo and Sandler). Many major environmental organizations are critiqued for promoting activist agendas that have little relevance to minority communities, and their understandings of relations to nature often differ from those of grassroots environmental activists of color (Anguiano et al.; Bullard, Dumping in Dixie). For instance, whereas traditional environmentalists tend to reify the separation between people and the “natural” world they seek to preserve and protect, environmental justice activists consider the places they live, work, and play all part of the environment and emphasize that people have a right to protection from environmental degradation (Bullard, Dumping in Dixie; Di Chiro, “Environmental Justice”). In fact, a common goal of environmental justice organizations is to combat environmental racism, which, according to Robert Bullard, “combines with public policies and industry practices to provide benefits for whites while shifting industry costs to people of color” (Dumping in Dixie 98, emphasis in original), as when toxic waste disposal sites or polluting industries are intentionally sited in communities of color.

Environmental justice activists often are influenced by and embrace other social justice movements, including civil rights, labor, religious, LGBTQ+, women’s, antiwar, and antinuclear movements, among others. Members of these sometimes-disparate groups “find common ground around the interrelated problems of toxic and hazardous wastes, air and water contamination, industrial pollution, workplace safety” and other issues resulting from industrial society (Fischer 120). For instance, in a study of nine grassroots environmental justice groups, Bullard found that most groups borrowed tactics from the civil rights movement, including public protests, rallies, sit-ins, boycotts, petitions, lobbying, and reports (“Anatomy”). Additionally, environmental justice leaders focus on common grassroots outreach efforts such as workshops and neighborhood forums to keep community members informed and engaged. Such efforts are about much more than the environment.

Environmental justice movements emphasize quality of life and “real and perceived threats faced in everyday living, working, and playing situations” (Allen et al. 123); recognize connections between the exploitation of land and of people; and acknowledge the real, embodied effects of environmental degradation on community members’ lives. For environmental justice activists who are already fighting toxic colonialism, the potential local effects of global climate change are not hard to imagine. Human geographer Anthony Leiserowitz argues that the lack of attention to climate change results from a dearth of “vivid, concrete, and personally relevant affective images of climate change” (1438). Recent research underscores this claim.

Consider a 2018 national survey conducted by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, which found that 70% of American adults think global warming is happening, yet only 41% believe global warming will harm them personally (Marlon et al.). As long as the public believes the effects of global climate change will be felt primarily by “geographically and temporally distant people, places, and nonhuman nature,” Leiserowitz claims, climate change and related environmental issues are not likely to become a priority in the United States (1437–1438). Yet for many people residing in marginalized communities, the effects of a rapidly warming world are not geographically or temporally distant. Climate change is exacerbating risks they already face, including air, water, and soil pollution; food insecurity; exposure to extreme heat; and inadequate housing and transportation, among others.

Scientific evidence backs up what community members already observe. For instance, studies have shown that Black, Latinx, and low-income communities disproportionately experience the effects of air pollution (Clark et al.; Mikati et al.; Tessum et al). And the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has made clear that people at the intersections of gender, age, race, socioeconomic status, caste, indigeneity, and disability are at highest risk from a rapidly warming world (IPCC). Many among these vulnerable populations already recognize this increased risk. Studies have shown, for instance, that people in Maryland households where members had one or more medical conditions or disabilities and/or were low income, racial/ethnic minorities, or residents of a floodplain saw themselves at greater risk from climate change (Akerlof et al.). Other studies have found that Latinx people are more likely than non-Latinx to believe global warming is happening, worry about its effects, and become politically active in response to climate issues (Ballew et al.; Leiserowitz et al.).

All of this data is important, but one thing these studies do not convey is the epistemological value of the specific stories community members tell about their embodied knowledge and local experiences, which often are the first harbingers of environmental risk in cases where official evidence does not yet exist. Mei Mei Evans states that personal testimonies are the “lifeblood of the environmental justice movement” because they convey the real, lived consequences of environmental injustice rather than abstractions (29). This is why environmental justice case studies (see, for example, Cárdenas & Kirklighter; Di Chiro, “Local Actions, Global Visions”; Pezzullo; Simpson) are so vital. Such case studies illustrate the importance of local knowledges and values in developing responses to local environmental risk and highlight specific ways community activists draw on cultural knowledges, grassroots science, and community praxis in fighting environmental racism (Chen et al.; Houston). Consider, for instance, climate activism in the predominantly Latinx Chicago-area neighborhood of Little Village.

In Little Village, climate change activism began in the early 2000s, as the community fought to close two heavily polluting coal-fired power plants nearby. That activism continues today, as members of the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization (LVEJO) engage in a culturally situated, multimodal approach to addressing local environmental and climate injustices. Studying and learning from the local, cultural, and embodied expertise of LVEJO is important as people in vulnerable communities “experience and cope with crises under very different conditions,” as Induk Kim and Mohan Dutta found in their study of activism in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. I employ Angela Haas and Erin Frost’s apparent decolonial feminist rhetoric of risk methodology to analyze a case study of activism in Little Village. This methodology combines apparent feminism (in which rhetoricians strive to make their own “subject position explicit, to hail allies in redressing sexism, and to critique ethics of efficiency”) and a decolonial rhetorical methodology, which “interrogate[s] and seek[s] to redress the colonial effects of risk and its scientific and technical rhetorics on the land, communities, knowledges, and lifeways” (Haas and Frost 170). This case study helps illustrate why we must recognize and learn from the local contexts in which climate justice activism is delivered.

An Apparent Decolonial Feminist Approach to Analysis

The case study I present here illustrates one way to identify and learn from the complex efforts of community activists who are making connections between local environmental concerns and global climate change. I employ Angela Haas and Erin Frost’s apparent decolonial feminist rhetoric of risk methodology, which brings feminist, Indigenous, and decolonial theories into conversation with Jeffrey Grabill and Michele Simmons’s critical rhetoric for participatory risk communication. This methodology assists me in honing in on how environmental justice activists in specific communities position their arguments in contrast to the patriarchal and colonial construction of environmental risk. It requires listening to and learning from individuals’ lived, embodied experiences with toxic colonialism and the myriad ways they experience and are affected by environmental contamination and climate change. This methodology prioritizes the stories of those who are most at risk, so they are able to participate in meaningful ways in the “construction of risk itself” (Grabill and Simmons 420). It also emphasizes a systems approach to risk and questions asymmetrical power relations, values underrepresented knowledges and embodied experiences, and redresses social injustices, addressing how climate change affects people in specific locations across multiple timescales. Haas and Frost’s methodology promotes “a deeper understanding of the interdependencies between local, global, and international risks and across economic, environmental, geopolitical, cultural, and technological risks,” and it makes connections between risks that have occurred historically, are occurring now, and will occur in the future (169). Haas and Frost position their methodology as a flexible heuristic for analyzing localized global risks (or the ways that risks to one community also relate at the local and global levels to risks faced by other communities), as is illustrated in the analysis that follows.

Long-Term Activism in Little Village

An apparent decolonial feminist rhetoric of risk values local rhetorics of risk, especially as they originate in particular kinds of bodies. In this case study, the bodies most at risk are predominantly Latinx, immigrant, and working-class people, residing in and around the South Lawndale (commonly called Little Village) community near Chicago. Specifically, this analysis focuses on the efforts of community members engaged with the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization (LVEJO), for whom climate change is an integral part of their activist agenda.

Little Village activists’ efforts have always originated in their embodied experiences with local environmental injustices. LVEJO was formed in 1994, sparked by parents’ initial concerns about dangerous particles children were exposed to during a local school renovation. The formation and longstanding efforts of this activist group have been aided in part by its location and the political context in which it operates. Beginning in the 1960s and continuing into the 1990s, neighborhood groups and community organizing became prevalent ways for specific Chicago-area communities to advocate for themselves in a city dominated by machine politics and clear borders delineating racial and economic demographics (see, for instance, Clavel; Squires et al.). In the 1980s in particular, Latinx community members became increasingly vocal within their neighborhoods as their population grew dramatically without proportionate political representation (Pallares). The homogeneity of many Chicago-area neighborhoods, including Little Village, has proven beneficial in that it leads to “group consciousness” and coalition building around common concerns, particularly those related to race and class (Cano 40).

In the late 1990s in Little Village, those concerns shifted to air pollution. After Little Village resident and LVEJO community organizer Kimberly Wasserman rushed her infant son to the emergency room because he had an asthma attack, she went door to door gathering residents’ stories of their own serious breathing issues. The realization that two coal-fired power plants were responsible for the high rates of asthma in their community led Little Village activists to spend twelve years building local coalitions and engaging in a variety of culturally situated, multimodal tactics to raise awareness about the environmental injustices they faced. These tactics combined traditional forms of activist writing such as letters to policymakers and local newspapers and information posted on the LVEJO website with culturally and locally situated material and visual rhetorics, including street art, street theater, protests, and toxic tours. Eventually, activists’ tireless and creative efforts at community and coalition building helped lead to the shutdown of the power plants.

This initial detection of their embodied experiences with asthma began in a similar way as many other environmental justice narratives, in which community members notice health problems occurring in their own families or among friends and neighbors that they suspect relate to local sources of contamination or pollution (Edwards). Often, the community members who first recognize these problems and seek to find out what is causing them are women, particularly women of color whose efforts are rooted in the minority communities in which they reside (Bullard; Taylor). More recently in Little Village, concerns over the embodied effects of the lack of access to green space, fresh and local food, public transportation, and more have led to a variety of activist efforts. These include transforming a Superfund site into the community’s first large park in 75 years, establishing a prolific community garden, advocating for a new bus line, leading toxic tours to educate people about the community’s toxic history and environmental justice efforts, raising awareness of the health effects of obesity, and fighting for immigration legislation. This broad approach to community activism is common among environmental justice organizations, which recognize that environmental issues connect to other social issues (see, for instance, Di Chiro, “Environmental Justice”; Field).

Little Village activists put their embodied knowledges into conversation with scientific evidence to persuade fellow community members, policymakers, and the broader public of their concerns. Initially, in fighting to shut down the coal-fired power plants, activists relied on a Harvard School of Public Health study about coal power plants in Illinois that attributed more than 2,800 asthma attacks, 1,500 emergency room visits, and 41 premature deaths per year to the nearby plants (Levy & Spengler). Yet they also convened “bucket brigades” of community volunteers who helped collect and analyze air samples to accurately gauge pollution affecting their community. Such data collection continues today.

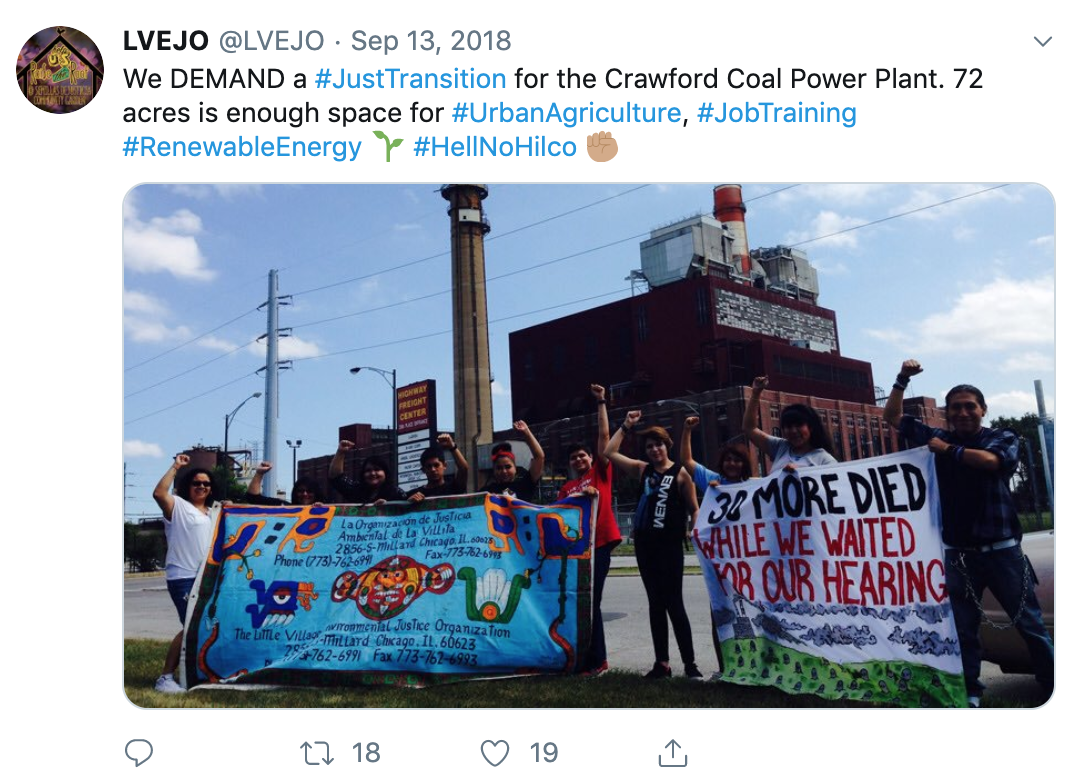

During their efforts first to convey the problems with the coal-fired power plants and now to advocate for action in response to global climate change, community activists artfully weave together their cultural, embodied, and scientific knowledges. At rallies and protests, many of the banners community members hold are written in Spanish or a combination of English and Spanish, further emphasizing the centrality of multiple languages to Little Village residents’ community and culture (see figure 1). Furthermore, the costumes worn for street theater performances and banners held up at protests demonstrate examples of what Haraway calls “art-science-activist worldings” (79). Activists’ colorful banners are so striking that they have been featured in a local art installation. Additionally, Facebook and Twitter are two prominent ways activists spread word about relevant local and global environmental and climate justice news, share information on upcoming events such as community garden potlucks and local climate justice marches, and educate community members on important environmental justice issues. For instance, recently LVEJO activists posted frequently about resistance to a proposed transformation of the closed Crawford coal-fired power plant into a logistics hub, which would increase diesel truck traffic and pollution. (Examples of different approaches to activist intervention into this issue are highlighted in figures 1–3 below.)

Figure 1. A screen shot of an @LVEJO Tweet showing activists protesting the proposed redevelopment of the Crawford plant and advocating instead for urban agriculture, green jobs training, and renewable energy in response to climate justice exigencies. Hand-drawn banners are prominent at local rallies, marches, and meetings alongside props (such as gas masks and papier-mâché cutouts), musical instruments, and street theater performances. All of these tactics, inspired by community activists’ cultural frameworks and shared values, help them “educate people in nontraditional ways, but ways that have been shown in our history and culture to be very effective,” according to activist Kimberly Wasserman (Thompson).

Figure 2. An LVEJO Facebook post asks Zapata Academy students, parents, and alumni to participate in the organization’s truck traffic study aimed at reducing toxic diesel truck traffic. Although LVEJO activists recognize the value of residents’ testimonies about the effects of local pollution, they also know embodied evidence is not enough to persuade city officials, environmental regulators, and others in positions of power. They regularly assemble local volunteers to assist with collecting scientific data to present alongside existing cultural and embodied knowledges.

Figure 3. An LVEJO Facebook post invites community members to a “Fighting for our Right to Breath” rally and meeting, with an infographic explaining the issue. Social media posts like this can reach community members who might otherwise be left out of planning discussions and assist LVEJO activists in communicating about climate justice issues in a way that is not “purposefully obfuscated, jargon-laden, or complex beyond the grasp of an interested public” (Peeples 207).

The seed of climate activism in Little Village was planted during the twelve years LVEJO activists and other Chicago Clean Power Coalition members promoted clean power alternatives to the local coal-fired power plants and participated in global warming town hall meetings. By 2011, discussion of “climate justice” was prominent on the LVEJO website. Today, LVEJO activists work to tactically intervene in environmental and climate injustices in as many ways as possible with the understanding that, as Haas and Frost point out, in local communities, “economic, environmental, geopolitical, societal, and technological risks are understood as inextricably tied” (169). The Semillas de Justicia garden in Little Village is one example of the ways brownfield redevelopment, zero waste and recycling, food and environmental justice, and climate adaptation and resiliency efforts—all vital components of LVEJO’s strategic plan (“LVEJO 2015–2020 Strategic Plan”)—are intertwined (see figure 4).

Figure 4. A screen shot of the “Community Garden” section of the LVEJO website, which showcases a slideshow of the Semillas de Justicia garden. The 1.5-acre garden—formerly a site for depositing leftover oil barrels—illustrates how climate justice efforts are integrated alongside LVEJO’s other goals. Organic gardening, sustainability, and climate adaptation workshops are offered at the redeveloped brownfield, which also serves as a gathering space and source of free, fresh food for community members.

Furthermore, LVEJO activists recognize that climate change and extreme weather events may disproportionately affect Little Village (“Climate Adaptation”) and that low-income people of color who comprise their community are “sources of important knowledge and solutions to climate change” with whom respectful engagement is key (“LVEJO 2015–2020 Strategic Plan”). To that end, local activists often share their own stories in person at community meetings, rallies, and other events and online via social media. They also seek to amplify the voices of fellow community members and ensure their experiences are being heard, as in the case of this tweet from July 2018 when LVEJO shared one woman’s experience with pollution (see figure 5).

Figure 5. An LVEJO Tweet shares the embodied effects of industrial pollution experienced by a community member named Gianna. In Little Village, such environmental health concerns are common. By sharing embodied evidence like this alongside their own and others’ scientific research, LVEJO activists are able to persuade their fellow community members to intervene in local climate injustices. Communicating via social media also enables some community members to engage with activist efforts even if their time and resources are limited.

Particularly notable are the ways LVEJO activists simultaneously seek to make tangible the effects of environmental racism and climate injustice and argue for a more sustainable and just future. Rather than focusing solely on the discussion of climate change, LVEJO activists integrate climate change advocacy efforts into other local concerns they seek to address because these local issues, ranging from food insecurity to industrial pollution, are intertwined with global climate change. Through artwork, infographics, written arguments, toxic tours, and more, LVEJO activists are able to take up Darryn DiFrancesco and Nathan Young’s call that “visuals and text should be considered together as ‘co-constructors’ of environmental narratives that, in combination, convey complex and multidimensional messages to media consumers” about climate change (520). The toxic tours, in particular, lend what Jennifer Peeples calls the “corporeal aspects of residents’ toxic epistemology” as visitors are invited to smell the air, meet residents, and “put their own bodies at risk, at least for the moment” (374). As activists conduct tours of contaminated sites in Little Village, they raise awareness of toxic chemical sites and the old power plants and make visible the material effects of industrial pollution, lack of green space, and public transportation on community members’ lives.

In these brief examples, the LVEJO activists are creating a locally focused conversation that, as Rebecca Jones states, demonstrates a “valuation of real bodies, their emotions, and experiences as an important component of public discourse.” Specifically, they continue to focus on reaching other members of the Little Village community to connect to fellow residents’ “own bod[ies], emotions, and intuitions as a method of conversing rather than appealing only to logic” (Jones). Although they draw on climate change data to support their arguments, Little Village activists also emphasize shared experiences, storytelling, artwork, and calls for collective action when conveying their messages to friends, families, and neighbors. They also build broader coalitions and navigate Chicago power dynamics in an attempt to be heard by decision-makers.

An Opening for More Action

The case study discussed above draws attention to how communities of color like Little Village are organizing to address environmental justice and climate justice exigencies. It is but one example of many ongoing environmental justice campaigns currently underway. From local instances of intervention like these, scholars, students, and community activists can learn new tactics for sparking climate change intervention in and across diverse communities. We must work to amplify the voices in those communities that will be most affected, to support their work and share it. One way we can do that is by archiving, analyzing, and sharing artifacts related to community members’ efforts at intervention, as I have advocated for elsewhere in relation to other environmental justice issues (Bates) and as I have briefly modeled in the case study presented here. This is work that our students can take up alongside scholars. For instance, in rhetoric and writing courses I teach, students collaborate on archival projects where they collect and analyze examples of local activist interventions or they pick a specific activist or group of activists—teens engaged in local climate justice marches, for instance—whose social media messages they collect and rhetorical tactics they analyze and share.

Beyond this pedagogical and archival work, we should engage community activists directly, learn from their stories, recognize their expertise, and connect to and stand in solidarity with them. As Phaedra Pezzullo and Catalina de Onís state, “[W]e have an ethical obligation to respond to crises and also to honor the people, places, and nonhuman species who share our world” (115), even if that means we must change “everything, including how we imagine our research, our relationships, our role(s) in the world, and, ultimately, ourselves” (114). We can invite local activists to speak to our classes and share their experiences. Furthermore, we can facilitate collaborations between our students, campus communities, and local activists—whether informally connecting them or more formally developing community engagement projects in our courses. Our students also can identify ways to expand local activist efforts into new spaces, such as their own neighborhoods, our college campuses, or online. To be truly rooted in an apparent decolonial feminist methodology, we must recognize and value the lived, embodied expertise of the community activists who are most affected. Solidarity efforts must be grounded in coalition building, ensuring that we (both professors and students) are working alongside the people who are the experts, seeking ways to support and amplify their work, not taking over their efforts or getting in their way.

We all are complicit in a system that aggressively pumps carbon into the atmosphere and distributes the chemicals and wastes of our daily life to areas predominantly occupied by Black, brown, and underrepresented bodies, a system that ignores these bodies. In response to the increased risk from climate change that vulnerable communities face, we can reduce our use of fossil fuels, pressure our campuses to become more sustainable, donate to environmental justice causes, and stand in solidarity with communities of color fighting these environmental injustices.

Akerlof, Karen L., et al. “Vulnerable Populations Perceive Their Health as at Risk from Climate Change.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 12, no. 12, 2015, pp. 15419-15433.

Allen, Kim, et al. “Becoming an Environmental Justice Activist.” Environmental Justice and Environmentalism: The Social Justice Challenge to the Environmental Movement, edited by Phaedra C. Pezzullo and Ronald Sandler, MIT Press, 2007, pp. 105-134.

Anguiano, Claudia, et al. “Connecting Community Voices: Using a Latino/a Critical Race Theory Lens on Environmental Justice Advocacy.” Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, vol. 5, no. 2, 2012, pp. 124-143.

Ballew, Matthew, et al. “Climate Change Activism Among Latino and White Americans.” Frontiers in Communication, vol. 3, 2019, doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2018.00058.

Bates, Julie Collins. “Activist Archival Research, Environmental Intervention, and the Flint Water Crisis.” Reflections, vol. 19, no. 2, 2020, pp. 208-239.

Bullard, Robert D. “Anatomy of Environmental Racism and the Environmental Justice Movement.” Confronting Environmental Racism: Voices from the Grassroots, edited by Robert D. Bullard, South Bend Press, 1993, pp. 14-40.

---. Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality. Westview Press, 2000.

Cano, Gustavo. “The Chicago-Houston Report: Political Mobilization of Mexican Immigrants in American Cities.” Research Seminar on Mexico and US-Mexican Relations, 30 Oct. 2002, The Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies, University of California, San Diego.

Cárdenas, Diana L., and Cristina Kirklighter. “Using a Hybrid Form of Technical Communication to Combat Environmental Racism in South Texas: A Case Study of Suzie Canales, a Grassroots Activist.” Communicating Race, Ethnicity, and Identity in Technical Communication, edited by Miriam F. Williams and Octavio Pimentel, Baywood, 2014, pp. 23-43.

Chen, Yea-Wen, et al. “Challenges and Benefits of Community-Based Participatory Research for Environmental Justice: A Case of Collaboratively Examining Ecocultural Struggles.” Environmental Communication, vol. 6, no. 3, 2012, pp. 403-421.

Clark, Laura P., et al. “National Patterns in Environmental Injustice and Inequality: Outdoor NO2 Air Pollution in the United States.” PLoS ONE, vol. 9, no. 4, 2014, doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0094431.

Clavel, Pierre. Activists in City Hall: The Progressive Response to the Reagan Era in Boston and Chicago. Cornell UP, 2010.

“Community Garden.” LVEJO.org, http://www.lvejo.org/our-accomplishments/community-garden.

Dickinson, Elizabeth. “Addressing Environmental Racism Through Storytelling: Toward an Environmental Justice Narrative Framework.” Communication, Culture & Critique, vol. 5, 2012, pp. 57-74.

Di Chiro, Giovanna. “Environmental Justice from the Grassroots: Reflections on History, Gender, and Expertise.” The Struggle for Ecological Democracy: Environmental Justice Movements in the United States, edited by Daniel Faber, The Guilford Press, 1998, pp. 104-136.

---. “Local Actions, Global Visions: Remaking Environmental Expertise.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, vol. 18, no. 2, 1997, pp. 203-231.

DiFrancesco, Darryn Anne, and Nathan Young. “Seeing Climate Change: The Visual Construction of Global Warming in Canadian National Print Media.” Cultural Geographies, vol. 18, no. 4, 2011, pp. 517-536.

Edwards, Nelta. “Radiation, Tobacco, and Illness in Point Hope, Alaska: Approaches to the ‘Facts’ in Contaminated Communities.” The Environmental Justice Reader: Politics, Poetics, and Pedagogy, edited by Joni Adamson, et al., U of Arizona P, 2002, pp. 105-124.

Evans, Mei Mei. “Testimonies.” The Environmental Justice Reader: Politics, Poetics, and Pedagogy, edited by Joni Adamson, et al., U of Arizona P, 2002, pp. 29-43.

Field, Rodger C. “Risk and Justice: Capitalist Production and the Environment.” The Struggle for Ecological Democracy: Environmental Justice Movements in the United States, edited by Daniel Faber, The Guilford Press, 1998, pp. 81-103.

Fischer, Frank. Citizens, Experts, and the Environment: The Politics of Local Knowledge. Duke UP, 2000.

Grabill, Jeffrey T., and W. Michele Simmons. “Toward a Critical Rhetoric of Risk Communication: Producing Citizens and the Role of Technical Communicators.” Technical Communication Quarterly, vol. 7, no. 4, 1998, pp. 415-441.

Haas, Angela M., and Erin A. Frost. “Toward an Apparent Decolonial Feminist Rhetoric of Risk.” Topic-Driven Environmental Rhetoric, edited by Derek Ross, Routledge, 2017, pp.168-186.

Haraway, Donna J. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Cthulucene. Duke UP, 2016.

Houston, Donna. “Crisis and Resilience: Cultural Methodologies for Environmental Sustainability and Justice.” Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, vol. 22, no. 2, 2008, pp. 179-190.

IPCC. “Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.” Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability, edited by Christopher B. Field et al., Cambridge UP, 2014, pp. 793-832.

Jones, Rebecca. “The Aesthetics of Protest: Using Image to Change Discourse.” enculturation, vol. 6, no. 2, 2009, enculturation.net/6.2/jones. Accessed 8 October 2019.

Kim, Induk, and Mohan J. Dutta. “Studying Crisis Communication from the Subaltern Studies Framework: Grassroots Activism in the Wake of Hurricane Katrina.” Journal of Public Relations Research, vol. 21, no. 2, 2009, pp. 142-164.

Leiserowitz, Anthony A. “American Risk Perceptions: Is Climate Change Dangerous?” Risk Analysis, vol. 25, no. 6, 2005, pp. 1433-1442.

Leiserowitz, Anthony A., et al. Climate Change in the Latino Mind. Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, 2017.

Levy, Jonathan, and John D. Spengler. Public Health Impacts of Criteria Pollutant Air Emissions from Nine Fossil-Fueled Power Plants in Illinois. Harvard School of Public Health, 2000.

Little Village Environmental Justice Organization (LVEJO). Call out to students, parents and alumni of Zapata Academy. Facebook, 8 March 2019, https://www.facebook.

Little Village Environmental Justice Organization (LVEJO). Invitation to join the Little Village community in Fighting for our Right to Breath. Facebook, 12 Sept. 2018, https://www.facebook.

“LVEJO 2015–2020 Strategic Plan.” LVEJO.org, www.lvejo.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/LVEJO_StrategicPlan_2020-2.pdf. Accessed 28 Aug 2019.

@LVEJO. “Gianna said she already struggles with pollution from existing industrial sites nearby, including odors that gave her trouble breathing and sometimes upset her stomach. ‘It’s not fair how everybody else gets to have clean air and not us,’ she said.” Twitter, 31 July 2018, https://twitter.com/LVEJO/status/1024346579254292480

@LVEJO. “We DEMAND a #JustTransition for the Crawford Coal Power Plant. 72 acres is enough space for #UrbanAgriculture, #JobTraining #Renewable Energy #HellNoHilco.” Twitter, 13 Sept. 2018, https://twitter.com/LVEJO/status/1040237368756920323

Marlon, Jennifer, et al. “Yale Climate Opinion Maps 2018.” Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, 7 Aug 2018, climatecommunication.yale.edu/visualizations-data/ycom-us-2018/?est=happening&type=value&geo=county.

Mikati, Ihab, et al. “Disparities in Distribution of Particulate Matter Emission Sources by Race and Poverty Status.” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 108, no. 4, 2018, pp. 480-485.

Pallares, Amalia. “The Chicago Context.” ¡Marcha!: Latino Chicago and the Immigrant Rights Movement, edited by Amalia Pallares and Nilda Flores-González, U of Illinois P, 2010, pp. 37-64.

Peeples, Jennifer. “Imaging Toxins.” Environmental Communication, vol. 7, no. 2, 2013, pp. 191-210.

Pezzullo, Phaedra C. “Performing Critical Interruptions: Stories, Rhetorical Invention, and the Environmental Justice Movement. Western Journal of Communication, vol. 65, no. 1, 2001, pp. 1-25.

Pezzullo, Phaedra C., and Catalina M. de Onís. “Rethinking Rhetorical Field Methods on a Precarious Planet.” Communication Monographs, vol. 85, no. 1, 2017, pp. 103-122.

Pezzullo, Phaedra C., and Ronald Sandler. “Revisiting the Environmental Justice Challenge to Environmentalism.” Environmental Justice and Environmentalism: The Social Justice Challenge to the Environmental Movement, edited by Phaedra C. Pezzullo and Ronald Sandler, MIT Press, 2007, pp. 1-24.

Simpson, Andrew. “Who Hears Their Cry?: African American Women and the Fight for Environmental Justice in Memphis, Tennessee.” The Environmental Justice Reader: Politics, Poetics, and Pedagogy, edited by Joni Adamson, et al., U of Arizona P, 2002, pp. 82-104.

Squires, Gregory D., et al. Chicago: Race, Class, and the Response to Urban Decline. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 1987.

Taylor, Dorceta E. “Women of Color, Environmental Justice, and Ecofeminism.” Ecofeminism: Women, Culture, Nature, edited by Karen J. Warren, Indiana UP, 1997, pp. 38-81.

Tessum, Christopher, et al. “Inequity in Consumption of Goods and Services Adds to Racial–Ethnic Disparities in Air Pollution Exposure.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 116, no. 13, 2019, pp. 60001-60006.

Thompson, Claire. “Meet the Woman Who Shut Down Chicago’s Dirty Coal Plants.” Grist, 15 Apr. 2013, grist.org/climate-energy/interview-wkimberly-wasserman-nieto-goldman-prize-winner/.

Yusoff, Kathryn. A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. U of Minnesota P, 2018.