LuMing Mao, University of Utah

(Published December 18, 2018)

Introduction: Reading Protest Then and Now

In 1885, three years after the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, the United States began to install the Statue of Liberty as a symbol of American welcome for the “huddled masses” of the world. To help to pay for the installation cost including building the base for the statue, the government launched a fundraising campaign soliciting the general public, including all Chinese, to contribute to this effort. Outraged by the hypocrisy and discrimination made legal by the Exclusion Act, one Chinese resident and student of New York, Saum Song Bo, wrote an open letter to expose the irony and hypocrisy and to denounce the racism that all Chinese had to endure as a result of this new legislation. Titled “A Chinese View of the Statue of Liberty,” the letter begins as follows:

Sir: A paper was presented to me yesterday for inspection, and I found it to be specially drawn up for subscription among my countrymen toward the Pedestal Fund of the Bartholdi Statue of Liberty. Seeing that the heading is an appeal to American citizens, to their love of country and liberty, I feel that my countrymen and myself are honored in being thus appealed to as citizens in the cause of liberty. But the word liberty makes me think of the fact that this country is the land of liberty for all nations except the Chinese. I consider it as an insult to us Chinese to call on us to contribute toward building in this land a pedestal for a statue of Liberty. That statue represents Liberty holding a torch which lights the passage of those of all nations who come into this country. But are the Chinese allowed to come? As for the Chinese who are here, are they allowed to enjoy liberty as men of all other nationalities enjoy it? Are they allowed to go about everywhere free from the insults, abuses, assaults, wrongs, and injuries from which men of other nationalities are free? (290)[1]

In this opening paragraph, and throughout the rest of the letter, Saum Song Bo exposes and makes a mockery of the hypocrisy of the government in soliciting the Chinese to contribute to the building of a pedestal for the Statue of Liberty while having passed the most discriminating law against Chinese immigrants and labors in the history of this young nation. How should we then read this letter of protest from 1885 in the twenty-first century, in the here-and-now? What can we learn from it as we confront the exigencies of our own time? One possible impulse is to read it, first, as a historical document; second, as part of our Chinese/Asian immigrant history; and third, as a text that may bring its meaning to bear on the present. This way of reading, at first brush, may not strike anyone as inappropriate or deficient. After all, the letter is a historical document, and there is everything to be gained if it can be used to inform our understanding of the present.

This way of reading, however, may very well represent a persistent tendency in engaging history to following a linear chronology of what happened (past), what is happening (present), and what will happen (future) and to practice a way of reading that may not readily allow for dialogism or critical imagination. That is, how can we use dialogism and imagination—making connections, seeing possibilities, and developing a critical stance or disposition—to broaden our viewpoints and to remake our interpretive frameworks (Royster 83)? While we surely can read the present through the lens of the past, what about the other way around? What about looking back from our current vantage point to understand our past and to prepare for what might become our future? Better still, what about bringing both past and present into simultaneous view, into a dialectical tacking that enables us to move between past and present, between different cultural and rhetorical contexts, and to move into a process of becoming over being?

This effort of mine to enact a dialectical tacking, to frustrate the linear orientation in engaging history, resonates nicely with the work by Jennifer Sano-Franchini, et al. in Building a Community, Having a Home, a history of Asian/Asian American Caucus at the Conference on College Composition and Communication. Their collection brings together across time and space moments and memories that would otherwise be considered insignificant or not marked as “foundings” (11). Consequently, the caucus history they have constructed does not inhabit in one single linear narrative. Instead, it resides in “multiple beginnings, re/visions, accommodations, resistances, and sustaining threads” (24), and it thus provides possibilities and potentials for “re/visioning the caucus and for reconceptualizing a community that foregrounds alliances, unexpected connections and coalitions, redefining the categorical terms we use to understand ourselves” (25).

In what follows, I propose to advocate a temporal turn for the study of Asian American rhetoric while using Saum Song Bo’s letter of protest as an example for illustration. In so doing, I move away from linear temporality, from seeing past, present, and future as discrete entities. I want to shine a light on rhetoric’s relationality or its eventfulness that encompasses past, present and future and that crosses geographical boundaries and spaces. To accomplish these goals, and to better situate my proposal in the broader context, I begin with a brief review of recent scholarship on Asian American rhetoric. Following that, I make a case for a temporal turn through a series of questions and through analogical reasoning that foregrounds mutual entailment and interdependence-in-difference. I then apply the temporal turn to a reading of Bo’s letter, suggesting that studying Asian American rhetoric in the present and as importantly present represents an example of practicing untimely temporality. I conclude this essay by further reflecting on the relevance of Bo’s letter to the present and on the importance of enacting a temporal turn for developing a new narrative for Asian American rhetoric now and in the future.

Challenging Chronological Hierarchy: A Case for a Temporal Turn

Since the publication of Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric in 2008, work on Asian American rhetoric has progressed in some significant fashions (Mao and Young). Through recognition, recovery, and re/presentation, growing scholarship has demonstrated how Asian Americans, both in history and in our own times, re/claim their discursive agency and authority, contest and transform representations by dominant discourses, and promote and practice a way of speaking and knowing that rejects and transcends biases, binaries, and borders (e.g., Adsanatham; Hoang; Shimabukuro). These works have further developed new and transdisciplinary methodologies, enabling us to re/frame Asian American rhetoric not as necessarily belonging to one nation-state but as traversing the boundaries of nation-states and as evidence of a dynamic rhetorical tradition that has been neglected, marginalized, or simply ignored (e.g., Ashby; J. Lee; Wang). Collectively, they have not only complicated and enriched our understanding of Asian American rhetoric but also are reshaping some of our deeply held assumptions about our own disciplinary identities and about our own methodological beliefs.

As we rhetoric and composition scholars continue to bring to the foreground how Asian Americans deploy languages and other symbolic resources to speak for and about themselves both in time and over time, we must also reflect more critically on what we are representing and how we are representing it. It is incumbent on us to cultivate, and indeed demand, an intersubjective and interdependent stance so that our own historically conditioned knowledge and dispositions can be appropriately examined and our own terms of engagement sufficiently imbued with a sense of accountability, interconnectivity, and vulnerability. [2] Once again, the pivot for or emphasis on self-reflexivity and accountability finds a ready echo in Building a Community, Having a Home, where the co-editors are both attentive to other “absent” voices and reflexive of their very own by moving beyond what is familiar and present and by appealing to other, yet-to-be familiar narrative constructions in historiography (Sano-Franchini, et al. 14). For example, how can we responsibly represent and speak with Asian American symbolic practices as rhetoric since many of them have hitherto been deemed as anything but? Further, can they be recognized as rhetoric without a predetermined context or beyond the chronology and linearity of the master narrative? That is, how can we represent these practices without relocating them according to an imposed chronological hierarchy or without—to appropriate Johannes Fabian—“the denial of coevalness?”[3] In other words, if Asian American rhetoric participates in an ongoing meaning-making process to disrupt those conditions that without fail anoint certain rhetorics as representing the point of arrival and being, what forms does it take to study the rhetorical work of Asian Americans most efficaciously? What methodology or analytical apparatus should we develop and deploy in order to promote and put to work such concepts as process, accountability, intersectionality, and transnationality?

To respond to these questions, and to move beyond the linearity of the master narrative, I suggest that a temporal turn be developed for the study of Asian American rhetoric. By a temporal turn I mean we recognize and put to practice that rhetorics, their contexts, and their practitioner identities are always the outcomes of practices that are both emerging and contingent. Further, such practices are always informed and shaped by an abiding presence of specificity, historicity, and multiplicity. Such a presence represents an integral part of rhetorical hybridity or what I have elsewhere called “heterogeneous resonance” (Mao 28). More importantly, by a temporal turn I mean that we engage Asian American rhetorical practices both in the present and as importantly present so that we can better resist or complicate linear temporality and promote the language of presence-and-absence.

Let me explain. Being in the present calls on us to productively negotiate between the meanings of the past and the exigencies of the present, and between the knowledge that is being produced right now because of what we know of the past, on the one hand, and the social and political circumstances of the present moment that resonate with or help to reframe those of the past, on the other. Being importantly present means that we stop placing Asian American rhetoric into a timeline other than its own, into a chronological hierarchy that places Euro-American rhetorics at its top, signaling the point of arrival or commencement of a real beginning. And we start engaging Asian American rhetoric according to its own timeline so that we can begin to demonstrate how it “significantly qualifies, defines, or otherwise shapes the culture” (Hall and Ames xv). As a result, we stop turning Asian American rhetoric, or other minority rhetorics for that matter, into silent or silenced handmaids to Euro-American rhetorics, and we begin to privilege process and becoming over permanence and linearity and to value experience and multiplicity of locations over reified or objectified knowledge and single points of arrival or commencement.

The idea of being importantly present also enables us to promote and practice what I call the language of presence-and-absence. By that I mean a meta-understanding that any rhetorical practice or its meaning in any given context is never complete and that being importantly present as a discursive condition or status is never permanent, not only because there are bound to be other meanings awaiting discovery, recovery, and/or recognition, but also because being importantly present necessarily entails or implies its latent or emerging opposite: absence or mere presence. In other words, being importantly present means being importantly present-becoming-absent/merely present. That is to say, there always is an excess of meaning in any given communicative act. And being importantly present and being absent or merely present stand in a relationship of independence, and one does not negate or exclude the other, though it may temporarily dominate the other. Meaning and its excess and presence of importance and absence/mere presence are parasitic of each other, and they constitute the yin and yang of rhetorical reality—hence the language of presence-and-absence. Advocating a temporal turn for engaging Asian American rhetoric precisely aims to underscore this language or this meta-understanding, to recognize and value, rather than flatten or diminish, rhetorical practices’ singularity, multiplicity, and fluidity. Corollary to this is a profound respect for local histories and traditions and for the development of terms of interdependence and interconnectivity to constitute and regulate representation of all discursive activities.

Perhaps not by accident, my pivot toward a temporal turn so far developed shares a welcome affinity with Michelle Ballif’s recent call to challenge “normative historical thinking” for historiography of rhetoric. According to Ballif, this kind of thinking “renders whatever happens, has happened, will have happened to a predetermined (linear) chronology of what happened (the past), what is happening (the present), and what will happen (the future)” (244). She urges us to “write histories that begin with this presumption of their always already untimely nature” and to “rethink history, how to write history, beyond traditional notions of linear temporality” (247; also see Sano-Franchini, et al. 14, 17, 24-25). Drawing on Ballif’s insight here, I suggest that studying Asian American rhetoric in the present and as importantly present becomes “untimely,” too. First, being in the present and being importantly present do not conform to the linear chronology of what happened, what is happening, and what will happen. Second, they seek to bring both past and present into a dialectical tacking through negotiation, critical imagination, and collective remembering. Third, they do so recursively, and in the process they shine a new light on rhetoric’s interdependence and relationality or its eventfulness beyond essence- and norm-based assumptions and approaches. To put it more succinctly, studying Asian American rhetoric in the present and as importantly present becomes an example of practicing untimely temporality.

Untimely temporality places a premium on immediacy, contingency, and local agency, too. Our engagement with the past now cannot help but speak to the present; meanwhile, echoing Sano-Franchini et al. again, our knowledge of the present and our present knowledge will make reference to or find resonance in the past. More directly put, untimely temporality sponsors a dialogic process where we remember, rejoin, reaffirm, and reclaim; where we make past an integral part of present and future; and we make past, present and future a process of becoming. This kind of dialogic process that emphasizes emergence and contingency also guards against reading the present into history or our own (present) biases in reading history. In so doing, we both foster a sense of tradition and claim a degree of authority, authenticity, and legitimacy for Asian American rhetoric. We further engage Asian American rhetoric in ways that valorize its heterogeneous agency and speak meaningfully to the present and future with a sense of continuity and collective memory.

Looking Back and Forth: Performing Untimely Temporality

I now turn to the past, to the letter of protest with which I started this essay. As noted at the outset, Saum Song Bo, a Chinese student and resident of New York, wrote this letter in protest of the legalized discrimination against Chinese immigrants and labors and the hypocrisy exhibited by the US government. The letter appeared in October 1885 in a missionary magazine, American Missionary, which was published by the American Missionary Association, a Protestant-based abolitionist group founded in 1846. The Association’s primary objective, according to its Constitution, is “to conduct Christian missionary and educational operations, and diffuse a knowledge of the Holy Scriptures in our own and other countries” (The American Missionary Association 3), and it was also among the pioneers in providing mission service to Chinese immigrants to California. The Association had also opposed the Exclusion Act and supported Chinese immigrants through its mission service (The American Missionary Association). The magazine was in operation from 1846 to 1934, and it had a circulation of about 20,000 in the nineteenth century.

In May 1882, the United States passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which practically barred all Chinese laborers from entering the country and further denied Chinese who had already been in the country the right to seek naturalization. It was the first law ever implemented to deny a specific ethnic group the right to immigrate to the United States. Originally proposed as a temporary law purportedly meant to be in place for a decade, the Chinese Exclusion Act actually lasted for sixty-one years. It would not be until December 1943 that the law was repealed by Congress. The passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act was the culmination of the widespread anti-Chinese and anti-immigrant sentiment of the time, as well as discriminatory measures and restrictions against Chinese migrant workers carried out at the state and city level prior to 1882.

Against this background of discrimination, bigotry, and terror came the fund-raising campaign in 1885 by the US government to ask its people, including all Chinese, to help pay for the installation cost of the Statue of Liberty. Infuriated by the hypocrisy and deeply offended by the injustice made legal by the Exclusion Act, Saum Song Bo rose to resist, to voice his opposition, to call on others to join him, by composing this open letter, which is included here in its entirety:

Sir: A paper was presented to me yesterday for inspection, and I found it to be specially drawn up for subscription among my countrymen toward the Pedestal Fund of the Bartholdi Statue of Liberty. Seeing that the heading is an appeal to American citizens, to their love of country and liberty, I feel that my countrymen and myself are honored in being thus appealed to as citizens in the cause of liberty. But the word liberty makes me think of the fact that this country is the land of liberty for all nations except the Chinese. I consider it as an insult to us Chinese to call on us to contribute toward building in this land a pedestal for a statue of Liberty. That statue represents Liberty holding a torch which lights the passage of those of all nations who come into this country. But are the Chinese allowed to come? As for the Chinese who are here, are they allowed to enjoy liberty as men of all other nationalities enjoy it? Are they allowed to go about everywhere free from the insults, abuses, assaults, wrongs, and injuries from which men of other nationalities are free?

If there be a Chinaman who came to this country when a lad, who has passed through an American institution of learning of the highest grade, who has so fallen in love with American manners and ideas that he desires to make his home in this land, and who, seeing that his countrymen demand one of their own number to be their legal adviser, representative, advocate, and protector, desires to study law, can he be a lawyer? By the law of this nation, he, being a Chinaman, cannot become a citizen, and consequently cannot be a lawyer.

And this statue of Liberty is a gift to a people from another people who do not love or value liberty for the Chinese. Are not the Annamese and Tonquinese Chinese, to whom liberty is as dear as to the French? [4] What right have the French to deprive them of their liberty?

Whether this statute against the Chinese or the statue to Liberty will be the more lasting monument to tell future ages of the liberty and greatness of this country, will be known only to future generations.

Liberty, we Chinese do love and adore thee; but let not those who deny thee to us, make of thee a graven image and invite us to bow down to it. (290)[5]

Here are some relevant questions for us to think about now: How can we read Bo’s letter of protest in the present moment? How can a temporal turn be enacted and untimely temporality performed? In what ways can we use the letter to help us better understand the ever-evolving relationship between the meanings of the past and the exigencies of the present? What are the resonances and dissonances between the knowledge that is being produced here-and-now and the social, political, and linguistic conditions that surrounded the making of Bo’s letter there-and-then? And how can we connect our engagement with these questions, with historical documents like Bo’s letter, to the ongoing efforts to make the study of Asian American rhetoric importantly present and an integral part of Asian American collective experience?

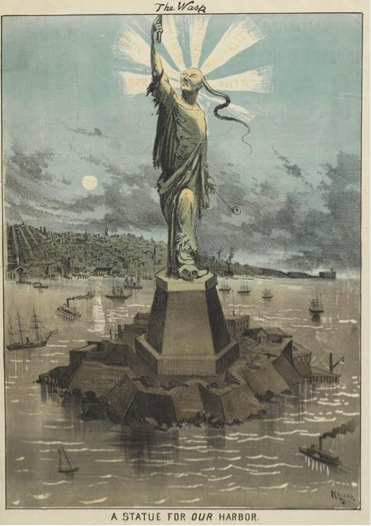

Before I respond to these questions, I want to look back a few years, to the year of 1881. In November 11 of that year, at the height of the anti-Chinese and anti-immigrant sentiment in the country, The San Francisco Illustrated Wasp published George Frederick Keller’s cartoon titled “A Statue for Our Harbor.” In a way, the publication of Keller’s cartoon, playing on the fears and anxieties of the country with respect to Chinese immigrant laborers, anticipated, or served as a barometer on, what was to come: the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act and the penning of the letter by Saum Song Bo.

George Frederick Keller/Historical Society of Pennsylvania.[6]

As one can see, Keller’s cartoon depicts a Chinese immigrant man standing on a pedestal surrounded by a harbor and with a moon with the face of a Chinese man shining in the night sky as its backdrop. He appears to have inherited all the major unflattering features associated with immigrant workers hailing from China: squint eyes, long, thin ponytail hair, and tattered clothes. His left hand holds an opium pipe, a symbol of decadence and addiction, and his right hand holds a torch with six beams of light, on which are written “filth, “immorality,” “diseases,” “ruin to,” “white,” and “labor,” words that were frequently used to depict Chinese immigrants or what they purportedly had brought to America and the white labor force then: filth, immorality, diseases, and ruin. Meanwhile, his right leg rests on a skull, signifying nothing short of doom and gloom and implying that such a fate would befall white Americans should the influx of Chinese immigrant laborers be allowed to continue.

What to make of such a portrait at this particular moment in history? For starters, it perpetuated the most demeaning stereotypes about the Chinese immigrants and fanned many of the rampant fears that were sweeping the country during that period—fears about how the Chinese immigrants were bringing ruin and destruction to the white working-class and to the cultural and moral fabrics of American society. These fears, as well as the rise of hate and bigotry, coincided with increasing measures of discrimination being enacted against the Chinese laborers, and together culminated in the final passage of the Chinese exclusion law in 1882, the very first time in American history when immigrants were barred from entry because of their race and class.

By visualizing the anti-Chinese sentiment of the time through imagery, symbols, and caricature, the cartoon appeals to, and indeed manipulates, the emotions of the public—their fears, anxieties, and prejudices. It helps instigate them to turn their raw emotions into action, into supporting discriminating measures against Chinese immigrants, into further inflaming the anti-Chinese sentiment and the perceived menace and threat they allegedly embody. It thus becomes part of the overall narrative of the time, one that constructs the Chinese immigrant laborers as depraved, as disease-bearing, invading the shores of the United States with ruinous consequences for its people. Such a narrative presaged the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, and it also propelled Bo to compose this powerful letter of protest so as to openly challenge this narrative and oppose the discriminating law.

Bo begins his letter by wasting no time to point to this situational irony with sarcasm and to call out the government for failing to live up to the ideals embodied in the Statue it was about to install. One can almost feel the palpable anger and outrage bubbling to the surface in this opening paragraph, as well as the contradiction being exposed between what the State of Liberty stands for and what the Chinese exclusion law means. By juxtaposing liberty with exclusion, and freedom with oppression, Bo succeeds in not only exposing the hypocrisy by the government’s capital campaign to ask the Chinese to contribute to the installation of the Statue of Liberty but also denouncing the legalized racism and discrimination against the same group of people. To drive home the point that the law has now made a mockery of the ideals enshrined in the Statue, Bo fires off a series of rhetorical questions to end the opening paragraph:

But are the Chinese allowed to come? As for the Chinese who are here, are they allowed to enjoy liberty as men of all other nationalities enjoy it? Are they allowed to go about everywhere free from the insults, abuses, assaults, wrongs, and injuries from which men of other nationalities are free?

Obviously, the answer to each of these questions is an unambiguous no. If no Chinese could be accorded liberty and freedom, both of which are tantalizingly promised by the Statue but denied to them by the law, why should they be asked to contribute to the Statue’s installation? This request by the government, therefore, epitomizes the hypocrisy, insult, and injustice all rolled into one. To further lay bare and challenge the discriminating nature of this law and its insulting and indefensible consequences, Bo goes on to provide a concrete example in the second paragraph:

If there be a Chinaman who came to this country when a lad, who has passed through an American institution of learning of the highest grade, who has so fallen in love with American manners and ideas that he desires to make his home in this land, and who, seeing that his countrymen demand one of their own number to be their legal adviser, representative, advocate, and protector, desires to study law, can he be a lawyer? By the law of this nation, he, being a Chinaman, cannot become a citizen, and consequently cannot be a lawyer.

Such an example, vivid and relatable, once again brings to the fore the injustice and discrimination that are being levied against the Chinese and appeals directly to the emotions of the American public for justice and equality.

There is an added irony to this entire event. The Statue is a gift from France. As one would expect, a government that doles out gifts that symbolize liberty and freedom would do all it can to respect and safeguard both. On the contrary, in the same year of 1885, the French government forced the people of Annan and Tonkin—the Annamese and Tonquinese Chinese—to give up their homeland to be absorbed into the French Empire. Once again, the hypocrisy being exposed here takes one’s breath away: a government deprives one people of their independence, freedom, and liberty while presenting another people with a gift that symbolizes all these rights. In the third paragraph of this letter, Bo confronts head-on such hypocrisy by once again deploying rhetorical questions in order to reclaim these rights for the Chinese in other parts of the world as well as for himself.

Against this level of hypocrisy, and against the nationwide hysteria and legalized discrimination, Bo wonders aloud, in the penultimate paragraph, whether it is this statute against the Chinese or it is the Statue of Liberty that would end up serving to tell the future generations about America’s liberty and its greatness. It is clear that he wants to believe in this country, in the liberty and freedom symbolized by and enshrined in the Statue of Liberty. However, it is equally clear his belief is being sorely tested, if not already battered or, worse still, shattered.

Bo ends his letter of protest as follows:

Liberty, we Chinese do love and adore thee; but let not those who deny thee to us, make of thee a graven image and invite us to bow down to it.

In this concluding, one-sentence paragraph, Bo personifies Lady Liberty and exhorts her not to be made into a false and empty image of honor and homage. With this emotional appeal as a coda, and by unrelentingly exposing the irony and hypocrisy throughout the letter, Bo delivers a scathing condemnation of two governments that have deprived the Chinese of their liberty, freedom, and independence while at the same time paying lip service to liberty and freedom with one government asking the same group to support a cause that symbolizes that which has been taken away from them.

Bo’s letter is rhetorical. Not only does he deploy a number of tropes including sarcasm, personification, rhetorical question, as well as emotional appeals, but he also directly responds to and intervenes in the exigency of his time. By exposing the glaring contradiction or hypocrisy between the law sanctioned by the US government and the fund-raising campaign sponsored by the same government, he confronts the increasingly blatant racism and legalized discrimination against the Chinese. With his personification of and evocative appeal to Lady Liberty, he calls on people of all nations to aspire to their highest ideals and to join with him to oppose racism and discrimination and to fight for justice, equality, and liberty for all.

To perform untimely temporality, we must then move beyond treating it as some historical artifact that just belonged to a discrete past, and we should look both back and forth, and do so recursively. For example, as our gaze moves into the present, we can start looking for parallels between past and present so that we learn from that past to inform our responses to the exigencies of our own present, including our ongoing struggle against economic injustice and racial discrimination and violence directed toward immigrants, toward ethnic minorities. As Erika Lee reminds us, for example, while the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed more than fifty years ago, “the legacies of Chinese exclusion remain embedded in American gatekeeping, especially in the government’s recent efforts to control both U.S.-Mexican border and Mexican immigrants” (195). Similarly, as we look back again, our view of the letter can become richer and sharper because what is happening in the present moment can help us better understand those concomitant social, political, and economic conditions that gave rise to bigotry, discrimination, and violence, and that propelled the making of Bo’s letter. We can also better appreciate those other voices that emerged in the wake of Bo’s letter in support of his stance and in direct opposition to discrimination and injustice.

For example, just two months after the publication of Bo’s letter, Reverend F. P. Woodbury wrote an article in the same magazine, in which he condemned the Exclusion Act by calling it “ludicrous,” “revolting,” and “the very barbarism of terror” (369). He also gives praise to Bo’s letter and to his bravery. In a direct response to Bo’s remark in the fourth paragraph of his letter—“whether this statute against the Chinese or the statue to Liberty will be the more lasting monument to tell future ages of the liberty and greatness of this country”—Woodbury expresses optimism and places hope in the ideals symbolized by the Statue of Liberty. He writes: “Despite all bills of Congress and all hoodlum riots, we believe in the statue as against the statute. We believe in the main steady current of American devotion to liberty, and not in a single eddy here or there, a mere swirl of filthy foam soon to be swept away by the mighty stream” (370). For Reverend Woodbury, Bo’s letter becomes part of this mighty stream that will wash away and wash out discriminating Washington and the “filthy foams” of hate and bigotry.[7]

There is more. As we look back and forth recursively, we must learn to view Bo’s letter within time and as an integral part of our collective experience. That is, we treat it as belonging to past, present, and non-time. Here I draw on Royster’s discussion of African conceptions of time encoded in two Swahili words, sasa and zamani. To be specific, sasa refers to “the present, the immediate past, and also the immediate future,” whereas zamani is “the past, the present, and also non-time, or a macro dimension in time, which is beyond both before (past) and after (future)” (Royster 79). Reverting back to my own term, sasa and zamani can be seen as untimely temporality writ large.

To be more specific, Bo’s letter belongs to or lives on a sasa-zamani time continuum. Namely, while the letter indeed was written by an individual in a not-too-distant past, it lives on in the present and future as long as we remember and make reference to it, and as long as there are or will be injustice, racism and discrimination around us. In fact, its relevance will not recede into the background when it enters into zamani time and “joins the community of spirits and achieving collective immortality” (Royster 79). It can no longer be merely present; having achieved collective immortality, it becomes importantly present, and it also takes part in the process of becoming as the community of sprits keeps expanding and takes on new memberships. In short, through a sasa-zamani time continuum, we gain a more dynamic understanding of the interdependency between the knowledge regarding the experiences of Chinese immigrants and laborers as depicted in the letter and the collective experience shared by all Chinese Americans and other minority immigrants to the US over time, including the present.

Now, with this letter living on the sasa-zamani time continuum, Bo has made himself listened to and heard and has become part of our collective experience. Through a confluence of agency, immediacy, and historicity, he catapults himself into a tradition of resisting political and social injustice and discrimination, reasserting a discursive agency and authority within the dominant culture, and carving out a space for Asian Americans to speak for and about themselves.

Conclusion: Protest Now and in the Future

Throughout this essay, with the help of Saum Song Bo’s letter of protest composed well over a century ago, I make a case for a temporal turn for studying Asian American rhetoric. Not only do I want to disrupt temporal linearity and the chronology of the master narrative but I also aim to engage both past and present in ways that foreground process and becoming and foster mutual entailment and interdependence-in-difference. This kind of engagement thus makes Bo’s letter of protest as relevant to us now as ever. For we are bound to find, as we look back and forth, many different and differing layers of resonance with the present. Meanwhile, our own protest right now against bigotry, injustice, and discrimination calls on us to reflect more critically on our own historically-conditioned knowledge and dispositions and on how best to continue this present work into the future, into our collective rhetorical experience. Throughout this process, I see myself performing two closely related discursive acts that are worth spelling out as part of this conclusion.

On the one hand, I want to read and remember Bo’s letter so as to capture a past that may have been forgotten or, worse still, erased altogether. I want to enrich our collective memory as Chinese/Asian Americans continue to deploy language and other symbolic means to make knowledge, fight discrimination, and seek justice and liberty for all. On the other hand, I want to represent the same past on terms of engagement that are not tethered to one single place or meaning but are generative of new meanings and significances. In other words, I want to develop and promote terms of engagement, such as untimely temporality, that recognize both meaning and its access and that embrace both being importantly present and being absent/merely present (read as the yin and yang of rhetorical reality). Out of these two discursive acts emerges a new narrative, one that is marked by an unmistakable sense of interconnectivity and a process of becoming and noncompletion. Such a narrative should become an integral part of Asian American rhetoric, further opening up new spaces where different modes of thinking can be valorized and deployed, and different chronologies and different histories composed and celebrated.

In short, reading and remembering Bo’s letter through the lens of a temporal turn requires that we recognize and give voice to its situatedness in the past and its resonance with the present. Equally important, we interrogate, in the process of representation, what Linda Alcoff calls “rituals of writing”—discursive practices of speaking or writing involving both the text or utterance and its position within a socio-cultural order (12). Advancing this kind of work necessarily embodies a dialogic process whereby we both assert or affirm its situated history and defer its meaning to a context that is continuously being recontextualized through untimely temporality. A temporal turn cannot help but make our engagement, now and in the future, of Asian American rhetoric both in the present and importantly present.

[1] Bo’s letter first appeared in October 1885 in American Missionary, a religious magazine published by the American Missionary Association. It was reprinted in East/West: Chinese American Journal (26 June 1986), and anthologized in The Columbia documentary History of the Asian American Experience in 2002, edited by Franklin Odo and published by Columbia University Press. The letter can also be accessed now in Cornell University’s Making of America digital library.

[2] Jacqueline Jones Royster refers to them as “passionate attachments.” She states that knowledge has “its sites, material contexts, and points of origin” and that its producers are “embodied and in effect have passionate attachments by means of their embodiment” (280).

[3] By that Fabian means “a persistent and systematic tendency to place the referent(s) of anthropology in a time other than the present of the producer of anthropological discourse” (qtd. in Saussy 95) so much so that the objects of anthropological study are put into the past and relocated in a chronological hierarchy, with the historian or the producer of anthropological discourse at its top and being the closest to “the eventual self-understanding of Spirit” (Saussy 95).

[4] Annam referred to the central region of Vietnam and Tonkin to northern Vietnam during the colonial era. In 1885 both became parts of French Indochina.

[5] The second commandment reads, “You shall not make for yourself an idol, or any likeness of what is in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the water under the earth. You shall not worship them or serve them” (The Bible, Exod 20: 4-5).

[6] Keller’s cartoon is part of the exhibit, “Nativism and Xenophobia,” at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (https://hsp.org/statue-our-harbor).

[7] Similarly, in the September 1887 issue of American Missionary, Yan Phou Lee, in his graduating address at Yale College, also issues a blistering condemnation of the discrimination and injustice leveled at the Chinese immigrants and labors by the US government and by the Exclusion Act.

Adsanatham, Chanon. Civilized" Manners and Bloody Splashing: Recovering Conduct Rhetoric in the Thai Rhetorical Tradition. Dissertation, Miami University, 2014.

Alcoff, Linda. “The Problem of Speaking for Others.” Cultural Critique, no. 20, 1991-1992, pp. 5-32.

American Missionary Association. History of American Missionary Association with Illustrative Facts and Anecdotes. New York: Bible House, 1891.

Ashby, Dominic. “Uchi/Soto in Japan: A Global Turn.” Rhetoric Review Quarterly, vol. 43, no. 3, 2013, pp. 256-69.

Ballif, Michelle. “Writing the Event: The Impossible Possibility for Historiography.” Rhetoric Review Quarterly, vol. 44, no. 3, 2014, pp. 243-55.

The Bible. English Standard Version, Faithlife.com, 2018.

Bo, Saum Song. “A Chinese View of the Statue of Liberty.” American Missionary, vol. 39, no. 10, October 1885, p. 290.

Hall, David L., and Roger T. Ames. Anticipating China: Thinking through the Narratives of Chinese and Western Culture. SUNY P, 1995.

Hoang, Haivan. Writing against Racial Injury: The Politics of Asian American Student Rhetoric. U of Pittsburgh P, 2015.

Keller, George Frederick. “A Statue for Our Harbor.” The San Francisco Illustrated Wasp, 11 Nov. 1881. Thomas Nast Cartoons, 14 Feb. 2014. https://thomasnastcartoons.com/2014/02/14/a-statue-for-our-harbor-11-november-1881/

Lee, Erika. At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration in the Exclusion Era: 1882-1943. U of North Carolina P, 2003.

Lee, Jerry. “Semioscapes, Unbanality, and the Global Reinvention of Nationness: Global Korea as Nation-Space.” Verge: Studies in Global Asias, vol. 3, no. 1, Spring 2017, pp. 107-136.

Lee, Yan Phou. “The Other Side of the Chinese Question.” American Missionary, vol. 41, no. 9, September 1887, pp. 269-73.

Mao, LuMing. Reading Chinese Fortune Cookie: The Making of Chinese American Rhetoric. Utah State UP, 2006.

Mao, LuMing, and Morris Young, editors. Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric. Utah State UP, 2008.

Royster, Jacqueline Jones. Traces of a Stream: Literacy and Social Change among African American Women. U of Pittsburgh P, 2000.

Sano-Franchini, et al., editors. Building a Community, Having a Home: A History of the Conference on College Composition and Communication Asian/Asian American Caucus. Parlor P, 2017.

Saussy, Haun. Great Walls of Discourse and Other Adventures in Cultural China. Harvard UP, 2001.

Shimabukuro, Mira Chieko. Relocating Authority: Japanese Americans Writing to Redress Mass Incarceration. Utah State UP, 2016.

Wang, Bo. “Rethinking Feminist Rhetoric and Historiography in a Global Context.” Advances in the History of Rhetoric, vol. 15, no. 1, 2012, pp. 28-52.

Woodbury, Reverend F. P. “Address on the Chinese Work.” American Missionary, vol. 39, no. 12, December 1885, pp. 368-70.