Kevin Roozen, University of Central Florida

Joe Erickson, Angelo State University

Enculturation: http://www.enculturation.net/multiple-engagements (Published: April 7, 2014)

[Editor's Note: Full Title for this article is: "Doing Two-Dimensional Design, Arranging American Literature, Crafting Creative Writing: Re-situating the Development of Discursive Practice Across Multiple Engagements" ]

Figures 1–5.

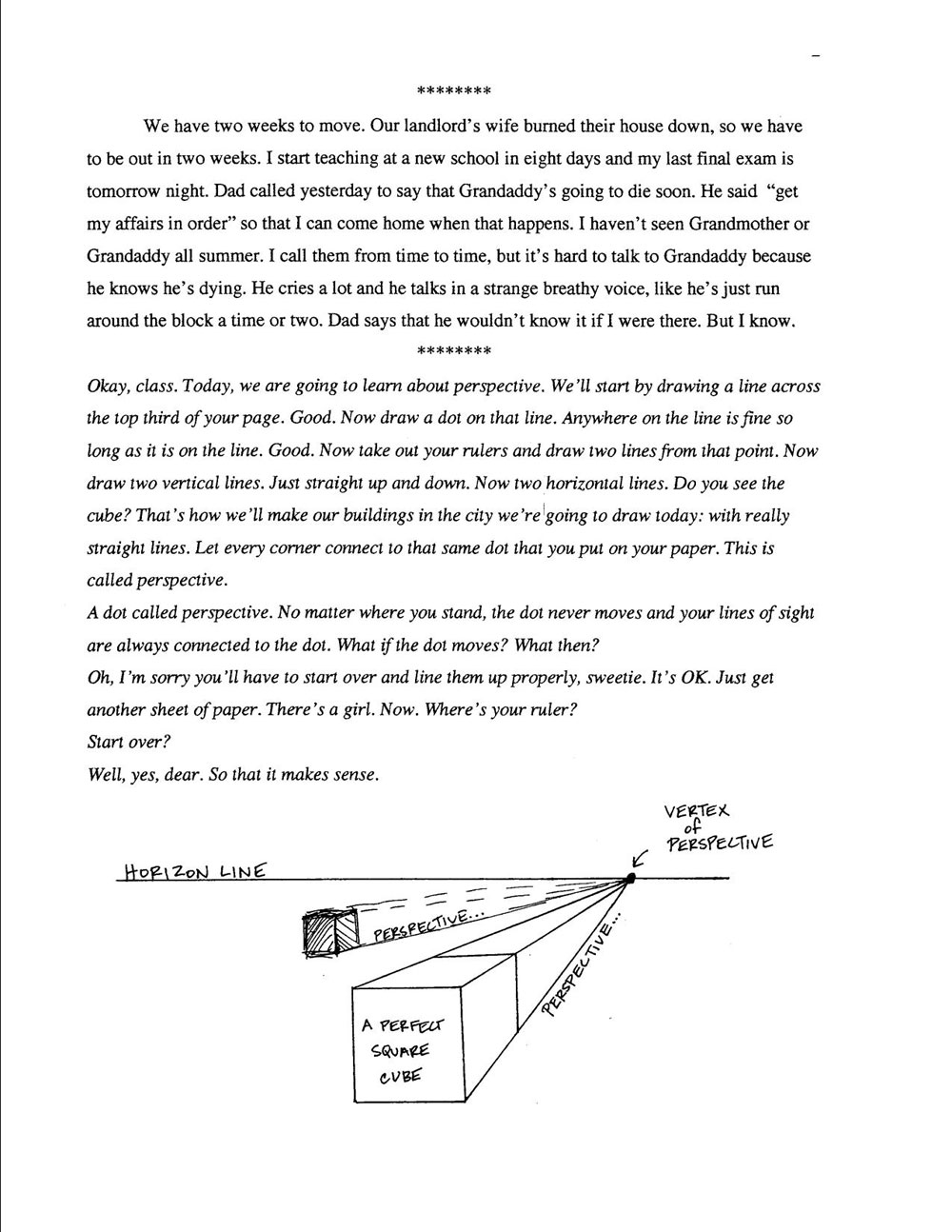

In crafting “Cotton,” the piece of creative non-fiction she was working on for her graduate course in Education focused on the teaching of creative writing, Lindsey Rachels (a pseudonym) spent several months continually organizing and re-organizing on various flat surfaces around her home pieces of paper containing textual descriptions and images representing some of the most poignant moments of her life—sometimes shuffling them around on her desk, dining room table, and countertops, and at other times taping them up on the walls and windows. The pages from Lindsey’s multiple drafts of “Cotton” shown above evidence her constant arranging and re-arranging of the prose and images she worked with. This “physical manipulation,” as she repeatedly referred to this practice during our interviews, was her way of coming to understand how these written and visual representations of a number of disparate events—her childhood visits to her grandparents, scenes of playing in the cotton fields that bordered her grandparents’ home, her pregnancy, memories of her grandfather’s passing—might be arranged to create a coherent lyric essay. According to Lindsey, the act of organizing and re-organizing these sections of text played a crucial role in helping her create a unified essay. “Without it,” Lindsey stated, “I couldn’t see how everything fit together, which piece goes where and how they all relate” (Interview July 30, 2009).

Lindsey’s mention of physical manipulation allowing her to “see” how the various written descriptions and images might be organized points toward its function as what Charles Goodwin refers to as a “discursive practice” (“Professional Vision,” 606). According to Goodwin, discursive practices are the “historically constituted architectures of perception” (606), the processes and procedures, through which a profession’s relevant objects of knowledge are shaped, produced, and understood. Describing the role of this shaping process in the production of knowledge, Goodwin writes, “[d]iscursive practices are used by members of a profession to shape events in the domain subject to their professional scrutiny. The shaping process creates the objects of knowledge that become the insignia of a profession’s craft: the theories, artifacts, and bodies of expertise that distinguish it from other professions” (606). In acting with the discursive practices privileged by a particular community, participants develop what Goodwin calls “professional vision,” “the socially organized ways of seeing and understanding . . . that are answerable to the distinctive interests of a particular social group” (606).

In his examination of the range of discursive practices used by archeologists and lawyers, Goodwin notes that seeing and understanding are often accomplished through acting with texts and inscriptions. The participants that Goodwin observe, for example, employ practices for tailoring documents so that the parts of them that contain information relevant to the action at hand are made salient, practices for making and using graphic representations, and practices for transforming observed phenomena into the objects of knowledge that animate a particular profession. Discursive practices also include acting with graph paper, rulers, tape measures and the “perceptual structures” that support the use of such tools. A wealth of situated studies have elaborated the discursive practices associated with a wide array of engagements, including trade workers jotting quick diagrams to cut and fit a piece of lumber or plumb a sink (Rose); lawyers preparing and arguing a case (Goodwin and Goodwin); shoppers using grocery lists (Witte); architecture students using sketchbooks (Medway “Writing and the Formation,” “Fuzzy Genres”); healthcare professionals interacting with patients (Nikolaidou and Karlsson; Schryer, Lingard, and Spafford; Schryer, McDougall, Tait, and Lingard); scientists and engineers acting with graphs, tables, charts, and other inscriptions and tools (Goodwin “Seeing at Depth,” “Transparent Vision,”; Latour Pandora’s Hope, Science in Action; Latour and Woolgar Laboratory Life; Pontille; Roth; Roth and Hsu; Suchman); childcare workers observing children (Tusting); dairy farmers managing their animals (Joly); ship workers docking a vessel (Hutchins); and persons using scrapbooking and diaries to document, organize, and reflect on events in their lives (Barton and Hamilton). For those engaging with these activities, these practices for acting with texts and inscriptions function as “ways of seeing in the world.”

In Mediated Discourse, Ron Scollon writes that the cultural resources persons act with are linked to two histories, “a history in the world [and] a history for each person who has appropriated it” (120). The discursive practice that Lindsey uses to transform the array of prose descriptions and visual images into a unified lyric essay certainly has an extensive history in the world of creative writers. The Writers at Work series of the Paris Review Interviews contains numerous references to this sort of physical manipulation from novelists, poets, and playwrights. Eudora Welty, for example, stated that after writing large chunks of prose, she would “revise with scissors and pins. Pasting is too slow, and you can’t undo it, but with pins you can move things from anywhere to anywhere, and that’s really what I love doing—putting things in their best and proper place . . . often I shift things from the very beginning to the very end” (“Eudora Welty” 290). Describing her writing process for Run River, Joan Didion indicated that she worked on the novel’s scenes in no particular order and then, once they were finished, “I would tape the pages together and pin the long strips of pages on the wall of my apartment” (“Joan Didion” 413). Describing Vladimir Nabokov’s writing practices, the interviewer notes that the author composes “his stories and novels on index cards, shuffling them as the work progresses since he does not write in consecutive order. . . . These cards are gradually copied, expanded, and rearranged until they become his novels” (“Vladimir Nabokov” 92-93). In physically arranging and re-arranging the images and prose vignettes to create her lyric essay, Lindsey participates in the historical constitution of this practice.

We are interested in the development of this discursive practice in Lindsey’s history, in how she has come to appropriate it, especially given that this was Lindsey’s first creative writing class. Our interest is motivated partly by Writing Studies’ long-standing interest in understanding the practices associated with writing and reading, particularly recent calls for fine-grained accounts of the development of those practices over time (Lewis, Encisco, and Moje; Street), and partly by calls for increased scholarship on the development of disciplinary writing expertise (Beaufort, College Writing, “Developmental Gains”; Artemeva). In response, we address two key research questions. First, what is the pathway of development of physical manipulation as a discursive practice in Lindsey’s history? Second, what role(s) might Lindsey’s engagement with other activities play in the development of the physical manipulation practice? While dominant perspectives would locate the development of this practice within Lindsey’s engagement with creative writing, we argue that attention to her participation with creative writing alone is insufficient to understand its ontogenetic path. We are arguing that the discursive practice Lindsey employs to arrange “Cotton” had developed along a lengthy historical trajectory of use across multiple activities including graphic design and literary criticism. Ultimately, our analysis argues for a more dispersed, complexly mediated and heterogeneously situated understanding of the ontogenesis of discursive practice.

Dominant Notions of Development

The dominant model for understanding the development of practice situates practice tightly within a bounded social space, and then views the person’s acquisition of practice as a result of regular and repeated encounters with that practice through increasingly deeper, fuller, richer engagement with that community’s activities. This model configures the person’s history of engagement with a focal practice in terms of his or her history within a particular community. This perspective is reflected in what Anne Beaufort refers to as composition studies’ dominant metaphor for understanding literate development, “one of writers moving from outsider to insider status in particular discourse communities or activity systems” (College Writing 24).

While this perspective affords fine-grained accounts of what animates a particular community (see, for example, the detailed accounts of disciplinary writing development offered by Beaufort; Dias, Freedman, Medway, and Pare; Freedman and Adam; Geisler; McCarthy), it configures histories of practices and persons, action, and artifacts in particular ways. One consequence of focusing on a particular community is configuring histories solely in terms of the spatial borders typically associated with a particular social space. Yrjö Engeström and Reijo Miettinen, for example, argue that dominant model “depicts development primarily as a one-way movement from the periphery, occupied by novices, to the center, inhabited by experienced masters of a given practice. What seems to be missing is movement outward and in unexpected directions” (12). Another consequence of focusing on a particular community is configuring histories solely in terms of the temporal borders typically associated with a particular social space. Engeström points to issues with the temporal framing, writing “the notion of time tends to be reduced to relatively discrete slices, often described in algorithmic terms with clear-cut beginnings and ends, dictated by given goals or tasks” (22). These observations are consistent with the critiques by a number of literacy scholars who argue that anchoring writing within a particular social space obscures connections to other times and places (Bartlett; Bartlett and Holland; Baynham and Prinsloo; Brandt and Clinton; Burgess and Ivanic; Collins and Blot; Reder and Davilla; Street).

These temporal and spatial boundings might not seem so unusual if we image a person’s participation with a particular disciplinary world or within a single engagement. And yet, consider how these temporal and spatial boundings serve to sever the historical trajectories persons trace as they live their lives, lives that play out through space and time and traverse multiple engagements across multiple timescales. Person’s lives are not confined to a single engagement; rather, they are forged across “trajectories of participation” (Wenger) or “chains of socialization” (Van Mannen) or “trajectories of socialization” (Wortham) that stretch across multiple activities. In “Place, Pace, and meaning: Multimedia Chronotopes,” Jay Lemke argues that rather than being confined to any single site of engagement, “[w]e make meaning along our lives’ traversals: across real and virtual spaces, across multiple institutions, genres, media, and semiotic systems. We do so in real time, across multiple timescales of action and activity, from the blink of an eye to the work of a lifetime” (110). Describing the daily life of a student, for example, Lemke traces a pathway that “will take him or her from classroom to classroom, from school to schoolyard, to street corner, to home, to the shopping mall, to TV worlds” (Lemke, “Across the Scales of Time,” 284).

Ontogenesis across Engagements

Our thinking about the development of Lindsey’s physical manipulation is informed by a body of work that understands social practice as emerging from repeated restructurings across multiple engagements1. In theorizing “the mode of generation of practice” in Outline of a Theory of Practice, Pierre Bourdieu identified “habitus,” “the system of transposable, durable dispositions, structured structures predisposed to function as structuring structures” (53) as playing a central role in generating and organizing practice. In describing habitus as “a past which survives in the present and tends to perpetuate itself into the future by making itself present in practices structured according to its principles” (82), Bourdieu emphasized its durability across the person’s multiple engagements throughout the life span. As a way to explain just how far its durability might extend through time and space, Bourdieu writes that “[t]he habitus acquired in the family underlies the structuring of school experiences. . . . and the habitus transformed by schooling, itself diversified, in turn underlies the structuring of all subsequent experiences. . . . from restructuring to restructuring” (87). It is from these continual restructurings across domains that practice emerges. From this perspective, practice is produced from being continually restructured as it is employed to meet the demands of present conditions. Accounting for how practice appears here and now, Bourdieu writes, is a matter of “relating the objective structure defining the social conditions of the production of the habitus which engendered them to the conditions in which this habitus is operating” (78). In other words, understanding how practice has come to be means attending to both “the social conditions . . . which engendered them” and their use in present conditions.

Informed by Bourdieu’s work, Ron Scollon’s Mediated Discourse: The Nexus of Practice offers a similar view in arguing that the re-use of practice throughout the life span crossing multiple sites of engagements is critical to its production. Based on his fine-grained analysis of the practice of handing being woven into different “nexus of practice,” which Scollon defines as a network of heterogeneous practices, some local and unique and some spun-off from other sites of engagements, he concludes that

[a] social practice is developed as practice through a sequence of social or mediated actions through which a person consolidates that practice in the habitus . . . across a variety of new or different situations. Of course this movement into new circumstances is always partial and always involves further adjustments and accommodations of the practice in the habitus to these new objective conditions. (141)

Similar to Bourdieu’s notion of “restructuring,” Scollon views practice as emerging from the continual “adjustments and accommodations” needed to refashion the practice for use in “new objective conditions” (141). When Scollon writes that “a practice is an action with a history,” (66), he does not mean a history of use within a single “nexus of practice,” but rather a history of use and re-use that extends across time and space and multiple engagements. “In this sense,” writes Scollon, “practice is always, to borrow Bakhtin’s terms, unfinalizable. A practice changes with each action as does the habitus of the social actor” (167). The “adjustments and accommodations” to the practice are not just relevant in refashioning them for use in present circumstances; they also figure prominently in opening up practice for potential future uses. “Each use,” writes Scollon, “elaborates and complicates” practice as it consolidated in the habitus, and “therefore each use opens up the potential for more complex uses” (135) in the near and distant future.

The elaboration of practice to meet the demands of new conditions often involves transformations across representational media. In a later work, Ron Scollon refers to these pathways of reuse across media as “discourse itineraries,” which he defines as “the historical path of . . . resemiotized displacements” (“Discourse Itineraries” 234). Kevin and his colleagues Paul Prior, Julie Hengst, and Jody Shipka refer to these transformations as “semiotic remediation,” which they define as “the reuse and re-representation of semiotic performances across modes, media, and chains of activity” (Prior, Hengst, Roozen, and Shipka 734).

Beyond merely tracing the movement of practice across space and time and multiple activities, this perspective also accounts how such movements can impact the development of practice. It invites us to locate the development of practice in chains of repurposings and remediations across time, space, and representational media. This framework also suggests that analysis of the development of practice should begin with examinations of the activity of persons in specific sites of engagement, but should also address how practices are restructured and semiotically remediated along historical trajectories that feed into and emanate from those sites. As an analytic lens, then, it accounts for both historical continuity and local, situated contingency in understanding how practice is acquired across an expansive landscape of activity.

Method

Participant and Setting

Kevin met Lindsey, a Caucasian female in her mid-twenties, in May of 2008. She was working toward her MEd in Secondary Education English Language Arts at a large public university in the southeast and teaching middle school Language Arts at a rural school in the area. As an undergraduate, Lindsey had initially pursued a double major in graphic design and English before concentrating solely on English during her final year and then, immediately after earning her BA, entered an MA program in English literature at another public university in the same area. After her first year of graduate school, Lindsey took a position teaching middle school English Language Arts and began taking classes to earn her teaching certificate, and then continued coursework toward her MEd. Kevin met Lindsey during a brief talk he had given during a workshop for local educators. Lindsey had been attending both as a current middle-school language arts teacher and as one of the graduate students leading the workshop. Kevin’s talk had focused on the kinds of literate activities that often go unnoticed by teachers, and as an example he had drawn from a case study of one undergraduate’s rich history with autobiographical journaling. Following the session, Lindsey approached Kevin to talk about her various types of journaling for a number of literate activities, including documenting the events of her life, understanding religious texts, working on papers for her English, generating material for her blog, and taking notes for her creative writing. Earlier that year, Kevin had received approval from his university’s Internal Review Board to study persons’ engagement with a broad range of literate activities. Because of her extensive engagement with a journaling for a wide variety of activities and her willingness to talk at length about them, Kevin asked Lindsey if she would be interested in participating in a research study focusing on her journaling, and she volunteered to do so.

Data Collection

Initially, Kevin began this case study to get a sense of Lindsey’s journaling practices, and had planned to conduct text-based interviews and ethnographic observation of her multiple journaling activities. To this end, the initial interview addressed Lindsey’s journaling for a number of purposes. While discussing her journaling, Lindsey mentioned a number of connections to other literate activities, particularly those associated with her processes and practices for creating literary analysis papers she had written for the literature courses she had taken as an undergraduate and a graduate student. These seeming connections between seemingly divergent writing activities struck Kevin as interesting, first because of the contrast between journaling and doing literary analysis, but also because linking these activities seemed to involve the repurposing of discursive practice across contexts. At this point, then, Kevin’s shifted the inquiry from Lindsey’s journaling activities to understanding the connections she forged among different literate engagements.

Lindsey’s comment about the connections between her writing processes and practices for different literate engagements suggested a method of data collection sensitive to the repurposing of practice across her processes of invention, production, and use for a variety of different engagements. To this end, Kevin conducted a series of process tracing interviews (Emig, 1971; Flower & Hayes, 1981; Prior, 2004; Prior & Shipka 2003) focused on texts and materials Lindsey provided me with from a number of her different textual activities. Process tracing involves having participants create retrospective accounts of the processes involved in the production of a particular writing project. In addition to providing a means to generate detailed accounts of discursive processes and practices used for specific tasks, these retrospective tracings also have the potential to illuminate activities and practices drawn from a wide array of engagements from the near and distant past. Rather than have Lindsey draw pictures of her process, as Prior (2004) and Prior and Shipka (2003) have done, Kevin asked her to describe the process involved in the invention and production of various projects by showing me how various texts and materials were employed. In addition to helping trigger and support Lindsey’s memory of the processes and practices she employed in the production and use of these materials, some of which had occurred ten years before, this form of “stimulated elicitation” (Prior, 2004) during the interviews also helped to make visible Lindsey’s tacit knowledge of text invention and production. It was frequently the case that we delayed scheduling interviews in order to give Lindsey time to locate and retrieve materials she had stored in her home or at her parents’ home in a neighboring state. All identifying information was removed from collected materials as Kevin received them. In addition to the focal texts for the process tracing interviews, Kevin made all of the other collected materials available to Lindsey by placing them in stacks within reach of the table where we conducted the face-to-face interviews in my office at the university.

The initial process tracing interview focused on the materials Lindsey provided for what she referred to as the feminine ideal project for a graduate English course, one of the most challenging papers she had written as an MA student in Literature. Successive interviews over the next twelve months focused on the materials Kevin collected for any engagements that Lindsey mentioned were relevant to the invention and production of the feminine ideal paper, particularly the two that from her perspective played the most prominent role in shaping that task: keeping her prayer journal and creating visual designs for an undergraduate course in graphic arts. The initial process tracing interviews tended to focus on one of these three engagements, but later interviews tended to move recursively back and forth across the materials for all of those engagements as well as others Lindsey had mentioned that were more recent than her writing as an MA student in Literature. Those engagements included some of the courses she had taken as a graduate student in Education, including a Composition Approaches for Teachers class and Web Design course. They also included her current work as middle school Language Arts teacher and her work on the curriculum she would be teaching at a new junior high school starting the next academic year. Multiple interviews over a period of twelve months provided opportunities for the kinds of “longer conversations” and “cyclical dialogue around texts over a period of time” that Lillis (362) identities as crucial for understanding practice within the context of the participant’s history. Lindsey’s frequent references to discursive practices and inscriptional tools she acted with to create the stacks of collected texts in Kevin’s office and her tendency to pick through them to select sample texts as a way to make a point or provide an example prompted me to start videotaping interviews and taking still photos in order to keep track of specific texts she indicated. Kevin examined all of the materials that were not employed as the focal texts for the process tracing interviews in order to confirm or disconfirm the use of the practices Lindsey described.

In all, Kevin conducted seven formal process-tracing interviews, which resulted in just over twelve hours of video- and audio-tape data, one process-tracing interview conducted via email, and took 60 still photographs during interviews or while he was examining Lindsey’s materials between interviews. The formal interviews were supplemented with dozens of follow-up questions Kevin developed while examining the interview recordings, his notes, and texts that Lindsey had brought to the interviews or had provided at other times. Kevin emailed these follow-up questions to Lindsey after the formal interviews and she emailed her responses, which usually arrived within the week and which he then printed and archived. Kevin also supplemented process tracing interviews with dozens of informal conversations throughout the data collection period. Notes were kept on eight of these informal conversations, which occurred during chance meetings on campus or when Lindsey stopped by Kevin’s office. All identifying information was removed from these data after they were collected. In all, Kevin read approximately six hundred pages of inscriptions (collected texts, key sections of transcripts of audio- and video-recordings of interviews, interview notes, and analytic notes), listened to and viewed more than a dozen hours of audio- and video-recordings, and examined dozens of photographs in order to develop a sense of Lindsey’s various literate practices and how she might be repurposing them across engagements.

Analysis

To identify Lindsey’s history of acting with particular practices, Kevin analyzed these data interpretively and holistically (Miller, Hengst, & Wang, 2003). Kevin first arranged data inscriptions (i.e., sample texts, sections of interview transcripts, interpretive notes, printed versions of digital photographs and still images captured from video, etc.) chronologically. Those data inscriptions were examined for instances where Lindsey had indicated or where it appeared that practices were being repurposed across contexts. For example, Lindsey had mentioned that she had reused what she referred to as her “physical manipulation” practice for creating visual designs while working on literary analysis papers as a graduate student. Further, while discussing the practice she used to arrange an essay she crafted for her Composition Approaches for Teachers class, Lindsey indicated that she had reused the physical manipulation practice she had employed for literary analysis. Lindsey also mentioned a practice of writing down verbatim some key phrases she heard during church sermons that informed her note-taking for several of her college courses. From Kevin’s perspective, it also appeared that Lindsey’s encounters with different uses of outlines for religious engagements, including the ones her father crafted each Sunday morning in preparation for teaching his Sunday-school class and also her engagement with sermon outlines that were printed in the bulletins both informed and were informed by her use of outlining for a number of school activities.

Based on that analysis, Kevin constructed brief initial narratives of Lindsey’s history of use of a number of practices across multiple engagements (e.g., an initial drawing of a flow chart that included by brief written notes in paragraph form supplemented with copies of the texts Lindsey had indicated during interviews) describing the use of a particular practice for one activity and then re-deploying it for another. Those initial narratives were reviewed and modified by checking those constructions against the data inscriptions (to ensure accuracy and to seek counter instances) and by submitting them to Lindsey for her examination. At these times Kevin often requested additional texts from Lindsey, and frequently she volunteered to provide him with additional materials and insights that she thought might be useful in further detailing the repurposing of discursive practices across contexts. It was frequently the case that Kevin’s understanding of the use of practices for these different literate activities needed significant modification as a result of closer inspection of the data, identification of additional relevant data, or discussions with Lindsey during interviews or via email. Kevin modified accounts of these interactions according to Lindsey’s feedback. Finally, Kevin asked Lindsey to member check (Lather, 1991; Stake, 1995, 2000) final versions of the trajectories in order to determine if they seemed valid from her perspective. The analysis produced a number of interesting narratives elaborating historical trajectories of practice-in-use across engagements.

Joe’s engagement with this analysis began in 2011 when our common interests in activity theory and genre theory brought us together to talk about the multimodal practices persons employ to mediate transitions across literate activities. While talking about some of our current projects, Kevin mentioned some of the practices that had emerged from the case study with Lindsey, which prompted a rich discussion about the theoretical and methodological approaches for making practices and their pathways of use visible and the pedagogical possibilities of valuing learners’ histories with such practices. That initial meeting led to a year of ongoing discussions via phone and over email about the reuse of practice and how that perspective informed our teaching for first-year composition and upper-division classes. The historical trajectories that had emerged from the study with Lindsey were frequently referenced during those talks, particularly those that flowed through school activities, and we began to look closely at some of the data inscriptions from those pathways. We eventually decided to collaborate on this article as a way to think even more carefully and systematically about what we were seeing in the trajectories and how they might best be represented.

We selected the narrative elaborating Lindsey’s use of physical manipulation practice presented below for a number of reasons. First, physical manipulation was one of the practices that Lindsey had talked a lot about and had identified as being central to many activities. Second, this narrative spans multiple different literate activities for multiple disciplines and spans a lengthy period of time. This allows for a longitudinal perspective and also provides a view of a practice being “elaborated,” to use Scollon’s term, multiple times and in different ways. Third, Kevin had closely examined and carefully mapped the trajectory of this practice and traced as it was employed to generate visual designs and then reused to do literary analysis. To represent Lindsey’s history of acting with this practice across multiple engagements, and also to make my own analytic practices more visible, we present the results of the analysis as a documented narrative rather than as a structuralist analysis, as Becker (2000) and Prior (1998) suggest. In addition to following the reuse of physical manipulation practice across activities, the use of documented narrative allows us to present these repurposings in a coherent fashion without flattening out the richness, complexity, and dynamics of how practices are reused and transformed across contexts. The visual images and the accompanying series of images that comprise the brief movies we offer throughout this article (such as the one we present at the beginning) are vital in this regard. In addition to representing the methods of inquiry used to inquire into the practices Lindsey employed to create a variety of texts for a variety of purposes, the images we offer allow are meant to help readers visualize how those practices animated the production of those texts. Because Lindsey had created these texts long before the interviews were conducted, it was not possible to capture Lindsey’s physical manipulation practice in action (except when she briefly demonstrated her use of the practice during a few of the interviews). Working in conjunction with our prose descriptions, the images of the texts and designs we offer are meant to help readers understand the practice that created them. In this regard, our use of visuals is in keeping with other scholars who provide visual images as a means of illuminating the discursive practices that mediate the textual action animating disciplinary worlds (Hutchins; Goodwin; Latour; Medway; Prior, “Remaking IO”).

The documented narrative that follows partially traces the developmental pathway of Lindsey’s “physical manipulation” practice as it is elaborated across three seemingly disconnected literate engagements. Scollon argues that any ontogenetic analysis must begin with understanding the origins of a particular practice in the life of the individual (Mediated Discourse 12). For the purposes of this article, we locate the origins of Lindsey’s physical manipulation in an undergraduate graphic design classes. We begin by describing Lindsey’s use of this practice for inventing and arranging visual designs. We then elaborate Lindsey’s repurposing and resemiotization of that practice to invent and arrange analyses of literary works for a graduate course in American Literature and, later, to invent and arrange “Cotton” for her graduate Education class.

Doing 2-D Design: “how disparate pieces can be ordered into a cohesive whole”

As an undergraduate majoring in graphic design, one of the first college classes Lindsey took was Two-dimensional Design, a demanding studio course that introduced students to basic principles of design including color, shape, orientation, line, and patterning and the processes and practices used by graphic designers. Describing the course, Lindsey stated that it focused on coming up with “workable” designs consistent with those basic principles and in ways that weren’t “obvious” or “predictable.” (Interview November 17, 2008). As she explained, “In graphic design, you are aiming to control the viewer’s eyes, where they go and when, what effects they perceive, how the elements of a piece work together. If you can’t achieve this, then your design doesn’t “work” or “hold up” (Interview November 17, 2008). Throughout the semester, students learned these principles by planning and executing a series of visual projects by hand using paper, pencils and pens for sketching and inking, glue, tape, scissors, X-acto knives, and so on. Doing it by hand, Lindsey indicated, encouraged students to commit to an idea and think about it carefully.

According to Lindsey, the professor devoted a great deal of attention to invention practices, particularly in terms of the arrangement of various elements of the design. Discussing the kind of textual practices that the instructor modeled and that she and other students employed as they worked on their projects for the course, Lindsey described a series of practices for physically manipulating texts2, including drawing figures in the sketchbook she used for the course, cutting shapes out of the sketchbook and arranging them on her table, orienting them in different directions, experimenting with different sequences, taping workable configurations together, and so on until she found a design that worked. Lindsey described her basic approach to her designs in the following way:

I would sit and wait to be struck by the idea. I’d create a shape, turn it, pair it with another, create another shape, roll it over […] sometimes it felt like aimless invention. I wasn’t sure what would be considered obvious, dull, boring. I was even less sure about what might be lauded as genius. Since we had to do everything by hand, I got used to sketching out the shapes and patterns before inking in a template. Before I could commit to a graphic, shape, pattern, or placement, I would draftand revise the thing endlessly. (Interview, November 19, 2009)

It is through this recursive process of creating graphic representations and physically orienting and moving them that Lindsey’s is able to envision and enact a workable design, one that wouldn’t appear “obvious, dull, [or] boring” from the perspective of a graphic designer.

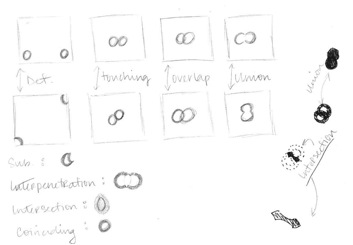

To get a clearer sense of the textual practices involved in this type of work, Kevin asked Lindsey to select one particular project that would serve as the focus of a series of text- and artifact-based interviews. She chose what she referred to as the “rings project,” a task that explored ways of depicting the spatial relationships between two shapes by arranging two rings in relation to one another in a series of different orientations, with the ultimate objective being to come up with a series that would guide the viewer’s eye along a particular path through four small panes. According to Lindsey, the initial steps toward generating her design involved sketching various panes and configurations of panes in her sketchbook, experimenting with different ways to orient the rings in relation to one another within each pane, and different combinations of panes. The images below offer a glimpse of Lindsey’s creative process for the rings project—the sketching of different orientations of the rings in her sketchbook, then cutting them out and moving them around in different orientations, numbering them as a way to keep track of their positionings, taping different series of sketchings together, and then inking the final version.

Figures 6–15.

This continual shuffling was necessary because “since our content was so limited, I had to focus most of my energy on the arrangement, how disparate pieces could be ordered into a cohesive whole.” “For the first week or so [after getting the assignment],” Lindsey recalled, “I was constantly sketching panes and rearranging them in every imaginable sequence in sketches in my sketchbook” (Interview, May 5, 2009).

Once she had sketched some panes that seemed to “work,” Lindsey’s next step involved physically arranging panes on her table in the studio and also at home on her kitchen table and desk, and eventually on the walls of her apartment. During one of our interviews, Lindsey described the process of arranging and re-arranging sequences of panes, and quickly sketching the diagram in the cluster of images shown above while she did so, stating,

I cut some of the panes out of the sketchbook or re-did them larger on other pieces of paper. Then I rearranged them in different combinations on my desk. When I saw something that worked, I taped the pieces of the project up on the wall above my drafting table and then continued to rearrange the pieces over the course of the next few days. When I liked a certain sequence or arrangement, I sketched it out on a piece of paper, or if it was a series of only four panes or so, I numbered them and recorded the various combinations that worked. Every now and then I sketched a new pane to replace one of the ones on the wall. (Interview August 12, 2008)

For Lindsey, this process of physically manipulating panes by moving them around, numbering them to keep track of various sequences of panes, and taping panes together as a way to stabilize particular orderings was much more effective and efficient than constantly sketching and re-sketching the entire series of panes every time she wanted to try a particular sequence.

Executing the final version of the project was basically a matter of creating a much neater version in ink of what was taped up on her wall. As Lindsey stated, “The sketched, pasted, and taped final version of the project was a template that I used. I simply copied it over, reproducing it in a cleaner, larger, sharper manner, staying up all night to ink it” (Interview, May 5, 2009).

Although each of the class’s other five projects emphasized different design concepts, Lindsey found that she could employ a similar process of sketching, cutting, taping, arranging, and re-arranging to complete them. For example, in describing the creation of another project for the class, one she referred to as “the gradation project,” a project which involved creating a particular pattern of shapes and then depicting that pattern as it changed shape, size, or orientation subtly over dozens of small panes, Lindsey stated,

for the project on gradation, which required that I ink a very intricate pattern and reproduce it twenty or so times, I needed to be certain that I had the core pattern down and I had to envision this strip as a part of the larger whole that I wouldn’t see until the project was finished, some 20 to 30 hours later. In order to save time, I learned how to draft and revise the pattern by cutting off pieces that weren’t quite right, taping on possible additions––loosely at first with masking tape––folding portions of the patterned strip back to see how it fit with a new design or segment I’d been working on, and rearranging bits of the pattern until I got it the way I wanted it. I wouldn’t know what ‘it’ was until I saw it. (Interview August 12, 2008)

As with her process for the rings project, the process Lindsey describes for the gradient project involves physically manipulating a representation by cutting, taping, and folding as a way to envision how the entire gradient will look with actually having to draw the gradient in its entirety.

In “Drawing Things Together,” Bruno Latour writes that “scientists start seeing something once they stop looking at nature and look exclusively and obsessively at prints and flat inscriptions” (15). In the same manner, it is only once Lindsey begins to sketch her representations of rings and shuffle them around on tables and walls that she is able to generate a design valued by graphic designers. Used in conjunction other discursive practices, such as the numbering system Lindsey used for keeping track of sequences of panes, the physical ordering and re-ordering of graphic representations allows Lindsey to make visible and available the representations she is working with, explore different configurations of those representations, and discover they might best be arranged into a coherent design. In other words, Lindsey’s ability to see the relationship between shapes in ways valued by graphic designers is accomplished through the competent deployment of the physical manipulation practice she used to transform the world into the categories and events that are relevant to the work of graphic design. It is the encounter between this practice and the sketched representations of rings, rather than the final resulting design, that is the key locus of graphic design, the real work of this disciplinary world.

In the next section, we detail Lindsey’s reuse of this discursive practice from the invention and production of visual arguments for graphic design into the invention and production of written arguments for a literary analysis at three key stages of her writing process: discovering an initial argument, generating a suitable strategy for developing that argument, arranging specific quotations to support her main points.

Arranging American Literature: “a hands-on patchwork feel”

While taking courses in her graphic design major, Lindsey was also enrolled in number of general education courses, including two introductory literature classes. Beginning with the second of those courses, which Lindsey was enrolled in concurrently with Two-dimensional Design, Lindsey was required to detailed analyses of literary works informed by secondary scholarship. As much as she loved the study of literature, Lindsey stated that researching and writing these analyses proved to be very challenging, particularly in regard to developing her own argument about the primary sources and using information from multiple secondary sources to support her interpretations. Lindsey stated, “The arguments, arrangements, and discoveries do not emerge as easily from texts and literary criticisms as they seemed to for my classmates. This sort of emergence requires hard study and work of digging into the research until I bump into something useful” (Interview November 17, 2008). As a way to address these challenges in the analysis of Homer’s Odyssey she did for her Introduction to Literature II class, Lindsey stated that she borrowed the discursive practice she had been using for her visual designs. She stated, “I was working on the paper on the Odyssey, and I had all of these different quotes. So, I took different quotes from all over and I taped them up on my window blinds in my room by my computer. I had them all over. I had them on the windows, I had them on the blinds, and I had them on the floor. And I just re-arranged them, and as I re-arranged them I started numbering them, then lettering them” (Interview August 12, 2008).

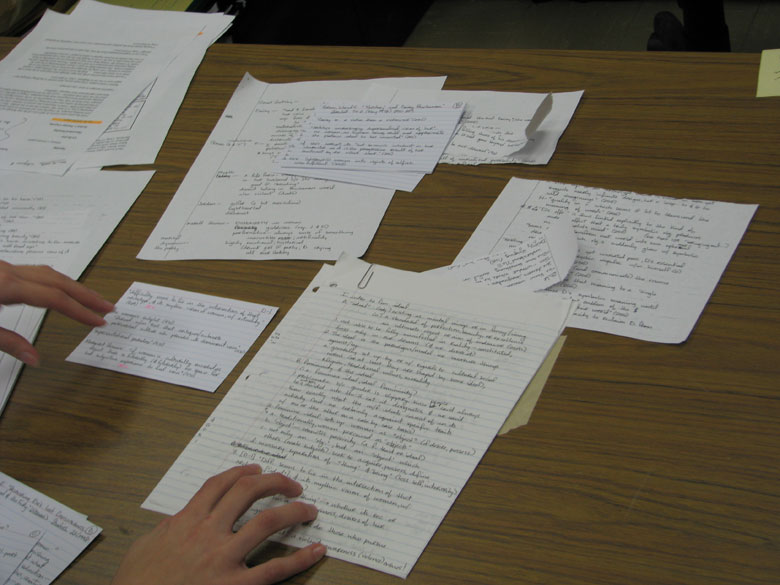

In order to get a better sense of how she assembled her literary analyses, Kevin asked Lindsey to select one particular paper that would serve as the focus of a series of process- and practice-based interviews. She chose a task she encountered for the American Literature course she took while earning her MA in English Literature, some three years after taking Two-dimensional Design. The task asked her to analyze two major novels and support her analysis with information from secondary sources. Lindsey chose to explore the treatment of “the feminine ideal” in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby and William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury and to support that analysis with half a dozen journal articles addressing Faulkner and Fitzgerald’s female characters. For Lindsey, the main challenge she faced was in finding a way of “talking about women in these two texts in a way that wasn’t trite and obvious” (Interview, July 30, 2009). Elaborating, she stated, “It was really hard for me. The first thing I had to do was figure out what they [the two novels] had in common, what each text was saying about the feminine ideal and how that fit together. To have to try to stick it all together was hard. I had never written a paper about more than one primary text before” (Interview, July 30, 2009).

As a way to discover her argument and how it might be arranged, Lindsey stated that she found the practice she employed for creating visual designs in Two-Dimensional Design to be very productive, and she recruited this practice into the invention and production of the “feminine ideal” paper in a number of ways.

As a first step, Lindsey repurposed this practice to develop a workable structure for her argument about the feminine ideal. According to Lindsey, this was one of the most difficult aspects of working on the paper: “I couldn’t get how to structure the paper. I just kept getting messed up when I had to keep jumping back and forth to talk about Daisy, then Caddy, then Daisy, then Caddy again” (Interview May 13, 2009). Lindsey met this challenge by spreading pages of passages3 she had copied verbatim from primary and secondary sources out on the floor of her room and then re-organizing them into different piles that addressed a common theme or point. Once she had organized her notes loosely by topic, she began arranging them into a tentative framework for the structure of the paper, working to determine in which order she might talk about the recurring topics she had identified while browsing her notes. “When I assemble papers,” she stated, “it’s like I read all of this stuff and I put, like I’m looking through these texts and they don’t go together, and then I’ll spread them all out on the floor and start putting them together in groups” (Interview, July 30, 2008). Lindsey acknowledged that this kind of arrangement would have been much easier had she done it on a computer, but stated that working on the screen did not allow her to get a broad sense of the various parts she had to work with or develop a sense of the various ways they might be fitted together. As she offered,

So by having all the papers spread out, it makes me step back. . . . It helps me to be able to touch it with my hands and move it rather than . . . cutting and pasting on the computer. That’s the other thing. I did everything by hand because once I would get on the computer you can’t see all the pages, you can’t see where all the stuff could go. . . . But when I have it in my hands, I can just pick it up and move it, and see where all the different pieces are and how they all go together. (Interview, July 30, 2009)

Spreading pages across the floor and grouping them according to topic allowed Lindsey to take in all the various passages she was working with rather than just the one or two pages of passages she would have able to view on a single computer screen. What eventually emerged from Lindsey’s sorting and shuffling on the floor was a rough but workable framework that first addressed the notions of the feminine ideal operating in the novels, then how those ideals were dismantled, and then the crises that resulted from that disruption. This process, Lindsey stated, “felt like [2-d design]” in the sense that “graphic design is just all about, like, doing things over and over again until it makes sense, and you can’t tell when it makes sense until it makes sense” (Interview, July 30, 2008).

Developing and supporting the three subsections of this initial framework required an even more nuanced organizing of the passages she had copied. To accomplish this, Lindsey drew on her design practice yet again to sort quotes from primary and secondary sources, this time by tearing off specific passages and assembling those pieces of paper together in smaller groups “like a puzzle” on her table and desk (Interview August 12, 2008). The images below offer a glimpse of Lindsey’s tearing sections from her notes and grouping those sections together as she demonstrated her process for assembling passages for the section of her paper about Daisy Buchanan’s voice.

Figures 16–19.

Demonstrating during a process tracing interview how this process helped her understand how this section of her argument might be assembled, Lindsey ripped and sorted sections from her notes while explaining,

I just took it [a page full of passages] like that [tearing a section from bottom of page] and laid it out and then I went through my notes and said “okay her voice, her voice, where is the quote about her voice?” So it talks about her voice right here [indicating a different page of passages], how her voice is “sad and lovely.” And here [indicating the second page of passages] it says “it was held by her voice.” So I took this [indicating again the second page of passages] like that [tearing a section from it] and put all these together. Then I knew that Person [author of one of the articles Lindsey used] had said something about Daisy’s voice [shuffling through notecards]. Right here [indicating a passage written on a note card containing passages from the Person article]. And so that [indicating the torn sections of notes] would go with what Leland Person said about “the essence of her promise represented by her voice.” (Interview January 16, 2008)

Lindsey would repeat this process, which she claimed “had a hands-on patchwork feel that I associate with the crafting of a piece of artwork” (Interview November 17, 2008) as she experimented with how the information she had in her notes might support the initial framework she developed.

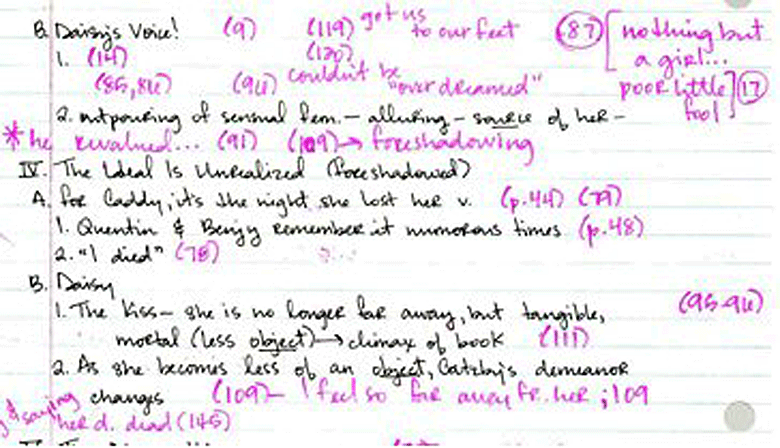

This discursive practice also played a prominent role as Lindsey created a series of increasingly detailed outlines of her argument. Understanding and making the connections among all the passages she had assembled posed a challenge for Lindsey. She stated, “I have to take rough, bare-bones ideas and connect them using sophisticated means or the reader will not envision the arrangements of ideas that constitute my argument” (Interview, November 17, 2009). “I come up with really good ideas,” Lindsey said, “but I have a hard time connecting them. It’s one of my biggest issues writing, period. I have all of these great ideas, and I can talk about it, but then when I actually have to weave it together, piece it together, I have trouble” (Interview July 30, 2009). In preparation for making a series of increasingly detailed and elaborate handwritten outlines at an even later point in the production of the paper, Lindsey taped combinations that “worked or felt right” (Interview January 5, 2009) up on the walls and windows around her desk. Describing the process she used to stabilize workable sequences, at least for the moment, Lindsey stated, “I just started tearing them out of the pages and taping them over each other so that I could tell what the thing was going to do. What I did is fold and then rip the notes and then I took masking tape, not clear tape but masking tape because I knew it would come off the wall, and I just taped them up all over the place. I had my textual evidence taped up in order on the walls and windows so that I could start doing my outlining” (Interview August 26, 2008).

The outlines Lindsey generated served as a means of ordering the passages into an even more precise arrangement. The images below offer a glimpse of some of the many outlines Lindsey created for the feminine ideal paper.

Figures 20–22.

Talking about her process of creating these outlines, Lindsey stated,

When I outline, I cut sections out, I write additions in different colored ink, and I manipulate the various portions that will make up the end product until I have something that is cohesive, logical. It’s an organic process where the final draft sort of emerges from the trying and retrying of ideas—will this quote fit best here or there? I used this quote earlier, but I think I need more of a lead-in to this portion of the text . . . I like this part of the novel and I want to be sure to represent it in the paper. How will I do that? What are the core ideas that will be the underpinnings of the paper? (Interview August 12, 2008)

If she felt fairly certain of how a passage was going to function in her discussion, she would position it within a structured outline and assign it a number or letter designating its position in the argument: “I am very particular about keeping it organized, like Roman numeral, capital A, number one, lower-case a. That’s a big deal” (Interview May 5, 2009). For the passages that she was as yet unsure of, she would indicate them by writing their page number in parentheses in no particular order in the pertinent section of the outline, indicating to herself that she needed to re-visit those passages to determine which ones to omit and then play around with the physical arrangement of the remaining ones to determine how they could help her develop her point. Once she had re-read the passages to understand them more thoroughly, and had physically manipulated the passages enough to develop a sequence that worked, she would write another outline, re-copying the material from the previous one that still worked and then making the additions or deletions she thought necessary. Discussing how she wove all of these activities and practices together as she fashioned her outlines for each paper, Lindsey mentioned she thought of the process in terms of using the “rigid form” of the outlines she’d used in AP English and then “combin[ing] it with what I was doing in the 2-d design where I was doing more manipulation of those materials, and then I applied it to the papers. This sort of allowing myself to physically shift things around but still maintain a kind of rigid form” (Interview August 26, 2008). In this sense, Lindsey stated, the process was like “graphic design” in that it was “just working with pieces of things and arranging them until they make sense” (Interview July 30, 2009).

Reflecting on her work on the feminine ideal paper, Lindsey stated, “I was proud of that paper,” and added that “it’s one of the only papers I’ve written where the argument came from me and then I went and found the criticism of them to back up what I wanted to say versus drawing everything from the criticism and not coming up with an original idea. . . . I had never found a way to dovetail research with my own ideas and this was one situation where I did that” (Interview, July 30, 2009). Both the A she earned on the paper and the professor’s single-sentence comment stating that “this is actually a rather good essay that makes cogent use of the critical sources as well as the original texts” suggest that Lindsey’s physical manipulation of passages helped her to invent a suitable argument and arrange textual evidence from primary and secondary sources to support and develop it.

To “see” the argument for the feminine ideal paper, Lindsey indicates that she drew upon the physical manipulation practice she previously used to create visual designs. This discursive practice allows Lindsey to make visible and available the passages she was working with, explore different configurations of those quotes and notes, and discover how they might best be arranged into a coherent argument. And yet, despite how suited this practice is to inventing and arranging her argument about the feminine ideal, it is important to remember Scollon’s comments this practice is only “partial” (121), that it does not fit literary analysis exactly, and thus requires a good deal of restructuring. Lindsey’s repurposing of this practice includes semiotically remediating it for use in developing a written argument. It also includes linking this practice with practices and tools that were not a part of generating visual designs, including the use of a highlighter, the use of outlines, and the practice of copying and recopying passages from sources on paper and notecards. It also includes linking this practice to those more local to literary studies, such as how literary analysis tend to be organized (introduction, body, conclusion), conventions for how quotes from primary sources and secondary sources then to work together, and so on. Likewise, it also includes coming to understand that some tools are incommensurable, such as the digitized cutting and pasting viewed on a computer screen. These resemiotizations and linkings with other practices and tools are how this discursive practice is structured for the work of literary criticism, at least for the moment. When we see when we encounter Lindsey’s physical manipulation of notes and passages for the feminine ideal paper, then, is the result of this practice’s previous use for graphic design and its present use for literary analysis.

Lindsey’s “adjusting and accommodating” (Scollon, Mediated Discourse, 141) this practice is indeed important for its use in inventing and arranging literary analyses. But, Bourdieu and Scollon’s work invites us to see that these kinds of adjustments are also important in terms of elaborating, or preparing, this discursive practice for repurposing for future uses. In the next section of the manuscript, we detail Lindsey’s further reuse of this discursive practice for the invention and arrangement of the multimodal lyric essay she crafts for a graduate Education class.

Crafting Creative Writing: “It was almost like pastiche”

Two years later, Lindsey took a position teaching Language Arts at a small, rural middle school in the southeast, and, while teaching, she decided to pursue a Master’s degree in Education at the university in the same state in which she had earned her Bachelor’s degree. One of the first classes she enrolled in was Composition Approaches for Teachers, a 6000-level course taught by a talented and experienced professor in the College of Education. Identifying the key objectives of the course, the professor stated, “the course will orient you to two approaches to the teaching of writing: an approach centered on writing exercises (the predominant approach in college creative writing programs and a widely-used approach in K-12) and the writing workshop approach that is the predominant approach to the teaching of writing as an art.” The course asked students to produce brief pieces in response to a series of writing exercises offered in a textbook titled Metro: Journeys for Writing Creatively, select their response to one of those exercises as the beginnings of their major project, and workshop it repeatedly throughout the semester to craft into a polished piece they would submit to a creative writing journal. Lindsey referred to the course as a “creative writing class,” and credited her interactions with the professor with helping her to view herself as a creative writer. “The professor,” Lindsey stated, “affirmed me as a creative writer. A lot of my teachers before had acknowledged me as an academic kind of writer, but she was the first one that showed me I was a creative writer” (Interview July 30, 2009).

As her major project for the course, Lindsey selected her response to the “Lost Childhood Places” exercise she had done during the initial weeks of class that invited students to write about a significant place during their childhood. In response to this prompt, Lindsey wrote a one-page, five-paragraph description of the cotton fields that bordered her grandparents’ home. Discussing the process she used to generate her response, Lindsey stated that “with creative writing, I just do it right on the computer. With the creative writing I could just do a brain dump, like, this is me and I’m an expert on me” (Interview, May 13, 2009). Contrasting her processes for creative writing with the one she used for literary analysis, Lindsey further noted that she did not use an outline “because I was the one who could decide how to organize it” and that she feel the need to copy passages from any outside sources out by hand because she did not have to do outside research to write about herself. “This is me,” Lindsey stated, “and I’m an expert on me” (Interview, May 13, 2009).

In revising and expanding her initial response throughout the semester, Lindsey drew upon the familiar discursive practice she had used for inventing and arranging her literary analyses in a number of ways. The initial linking of that practice into the lyric essay came was when Lindsey was asked to select from a series of revision strategies listed in the textbook. From the many listed in the book and the many that Lindsey read and considered, she chose a strategy the book referred to as “Paper, tape, scissors,” a strategy which involved taking the existing paper draft, cutting it into smaller sections with scissors, and then re-arranging those sections by taping them back together in different combinations. The point of this strategy, as explained in the textbook, was “to explore strange connections among words and the unexpected outcomes of textual collage” (185). Prior to employing the strategy they had selected, students were asked to provide to the professor in a short writer’s note a rationale for the revision strategy they had selected. In her note, Lindsey stated that the “‘paper, tape, scissors’ strategy appeals to me because I like to see the connections in various aspects of my writing come forth as disparate and isolated strings of words. I also like the physicality of this exercise.”

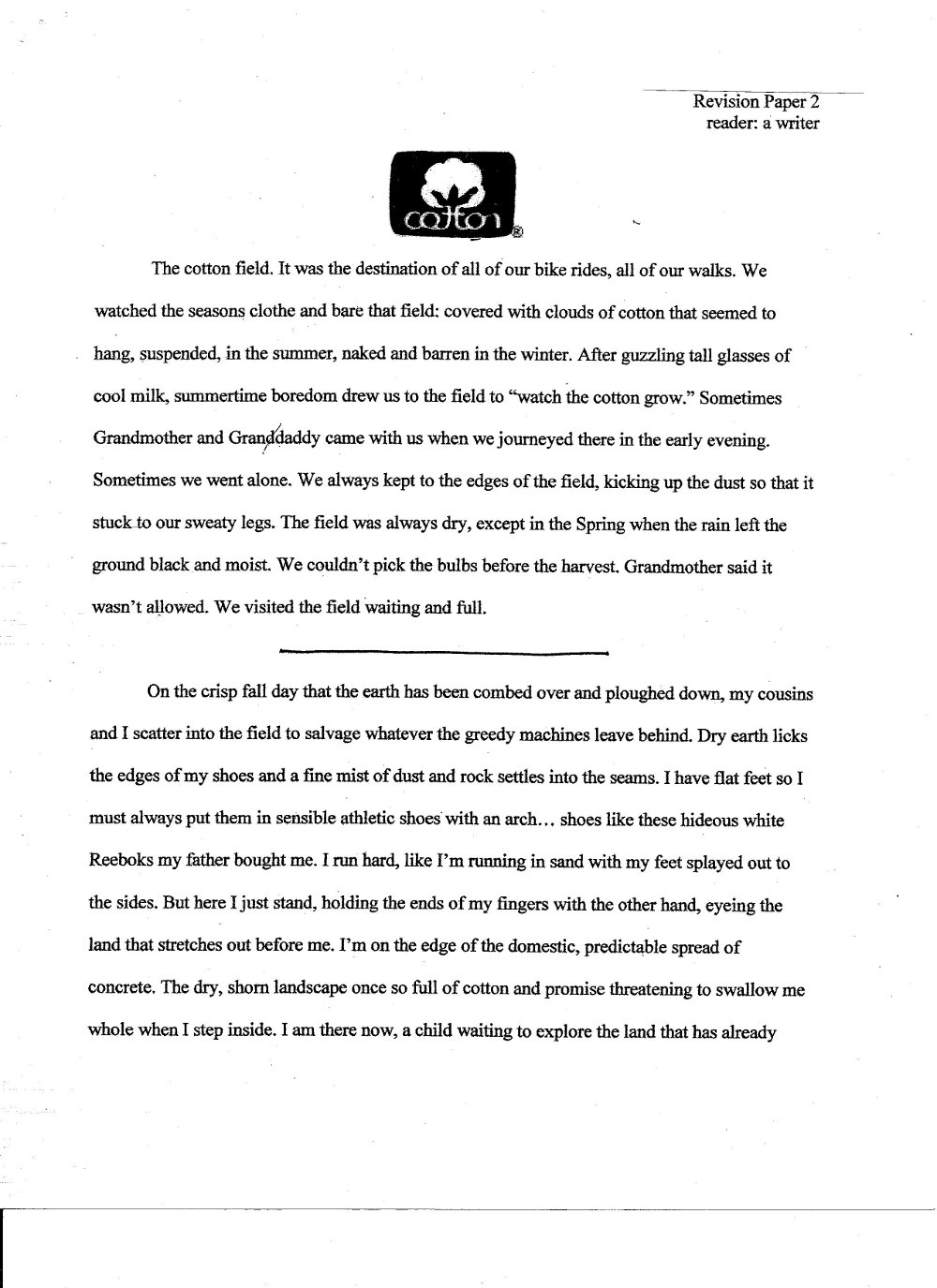

Using this strategy, Lindsey produced a four page typed draft consisting of nine paragraphs that focused on a number of her childhood memories of playing in the cottonfields near her grandparents’ home. The images below are the pages of Lindsey’s initial draft of “Cotton.”

Figures 23–28.

Through this strategy, Lindsey had substantially revised the paragraphs she had composed for the Lost Childhood places exercise. Only the two initial sentences and the brief final paragraph retained their same positions in the September 7 draft. The rest of the original paragraphs had been pried apart and new material added, including a detailed description of the activities she and her brothers used to engage in at the grandparents (i.e., climbing the big maple tree in the front yard, cutting roses, setting live traps in the garden), of her plans to make her own t-shirt from cotton bolls she’d picked from the field, and of the feel, look, and smell of the freshly-picked cotton bolls.

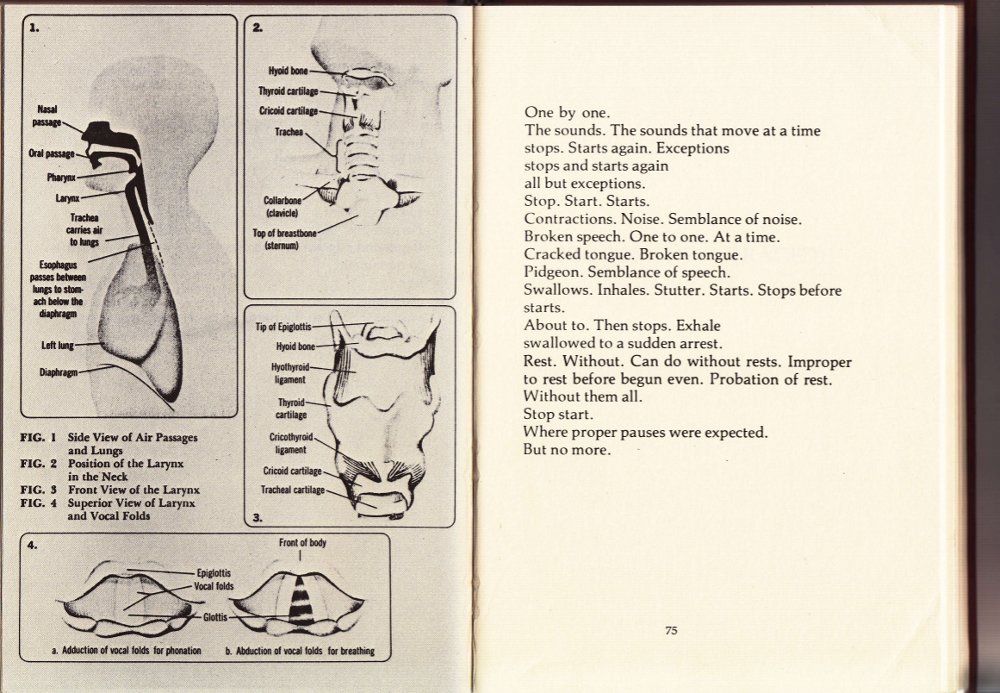

The handwritten notes on the pages of her September 7th draft indicate the ambitious plans Lindsey had for further changes to the piece. As she thought toward revising that initial draft, Lindsey wanted to build upon it to address a number of other topics, including her pregnancy and the recent passing of her grandfather. She envisioned four separate narratives that all connected to the cotton fields where she had played as a child. She also wanted to include a series of images that related to each of the vignettes. According to Lindsey, the idea to include the different topics and the images was prompted by her memories of some of the novels she had encountered during the courses she took while pursuing her MA in Literature. As she described it, “I started thinking about some of the books that I had read in graduate school, and I liked the way that it was all pieced together, how all the parts were disconnected, but there was still a theme that was woven through it” (Interview July 30, 2009). The images below are pages from two novels from her Postmodern Literature class that Lindsey mentioned specifically, Kathy Acker’s Blood and Guts in High School and Theresa Cha’s Dictee, showing the authors’ combinings of prose and image.

Figures 29–32.

Talking about these texts, Lindsey stated, “They were these fragmented texts and they had these drawings, and I was like, ‘I want to do that, that’s just cool.’ They have these really intricate drawings with the text, and they told a story without connecting the pieces for you” (Interview, July 30, 2009). These “memorial texts” (Witte 265) helped Lindsey envision how she could create a fairly unified essay from disparate elements without having to explicitly state the connections for her readers.

Using these texts as a model, Lindsey began enacting these changes by drafting the additional vignettes and assembling some images to accompany each of them. As she described,

So I wrote these little vignettes. Each section is like a separate vignette. I did the separate vignettes because I did not know how to collect them. So I would do these little vignettes and then I would do drawings of whatever occurred to me about the vignettes. Like if a drawing occurred to me while I was writing I would do these little sketches. The pictures gave me a way to break up the sections in a way that was aesthetically pleasing to me, and fun, inventive and fun to think about. (Interview, July 30, 2009)

Among the vignettes she added were two short descriptions of standing at the edge of a field after the machines had removed all the cotton and eating ice-cream in the evenings with her grandfather, and a longer one about a third grade art lesson about determining perspective. Some of the visuals she added, like the cotton trademark logo, an image of a boll weevil, and an old photograph of laborers picking cotton, came from the internet. Others, like the diagram of parts of a cotton boll and the diagram showing how to determine perspective, were drawn by Lindsey herself.

Arranging all of this to form a coherent essay posed a considerable challenge for Lindsey. Recalling the difficulty of trying to work everything into a coherent essay, Lindsey said, “I was trying to make sense of something that didn’t make sense, and it was too overwhelming for me to do by writing. There’s no way I could do an outline of this or even begin to try to write this” (Interview, May 13, 2009). In order to arrange all of this into a coherent essay, Lindsey drew upon the discursive practice she had used for her literature papers. The images below are of pages from the various in-process drafts of this lyric essay that Lindsey submitted for class workshops, all of which evidence the arrangement, re-arranging that she is doing.

Figures 33–47.

Describing how she ordered the prose vignettes, Lindsey stated “It was almost like pastiche. So I would just write segments, and because I couldn’t figure out how they all went together, I cut out all the segments. That was how I organized that draft, was to cut out all the pieces and then sort of, I put them together on my dining room table” (Interview, June 13, 2009). Elaborating, she stated,

I had been doing this thing when I was taking lit[erature] classes where I’d tear up my notes and move them around until I could figure out how everything fit, so I decided to just do that for [the creative writing piece]. So I took the paper and cut it into strips. And then I would cut it up and rearrange which pictures I thought introduced [each vignette] the best. So then I took the strips of all these different narratives and I started like assembling them with tape, so I literally just taped them together onto full pieces of paper. (Interview, June 13, 2009)

Describing how she determined the pairings of images with vignettes and determined how the pairings would be ordered, Lindsey stated that she employed a similar process: “I would cut [the vignettes] up and rearrange which pictures I think introduce them [each vignette] the best. And it’s all manual, like I just taped them together” (Interview, July 30, 2009). Throughout the rest of the semester, based on comments and suggestions she received from multiple workshop sessions, Lindsey used this practice to arranged and rearranged the vignettes and images, pausing frequently to stabilize the orderings as she expanded and enriched the details in the vignettes and experimented with different visuals to use.

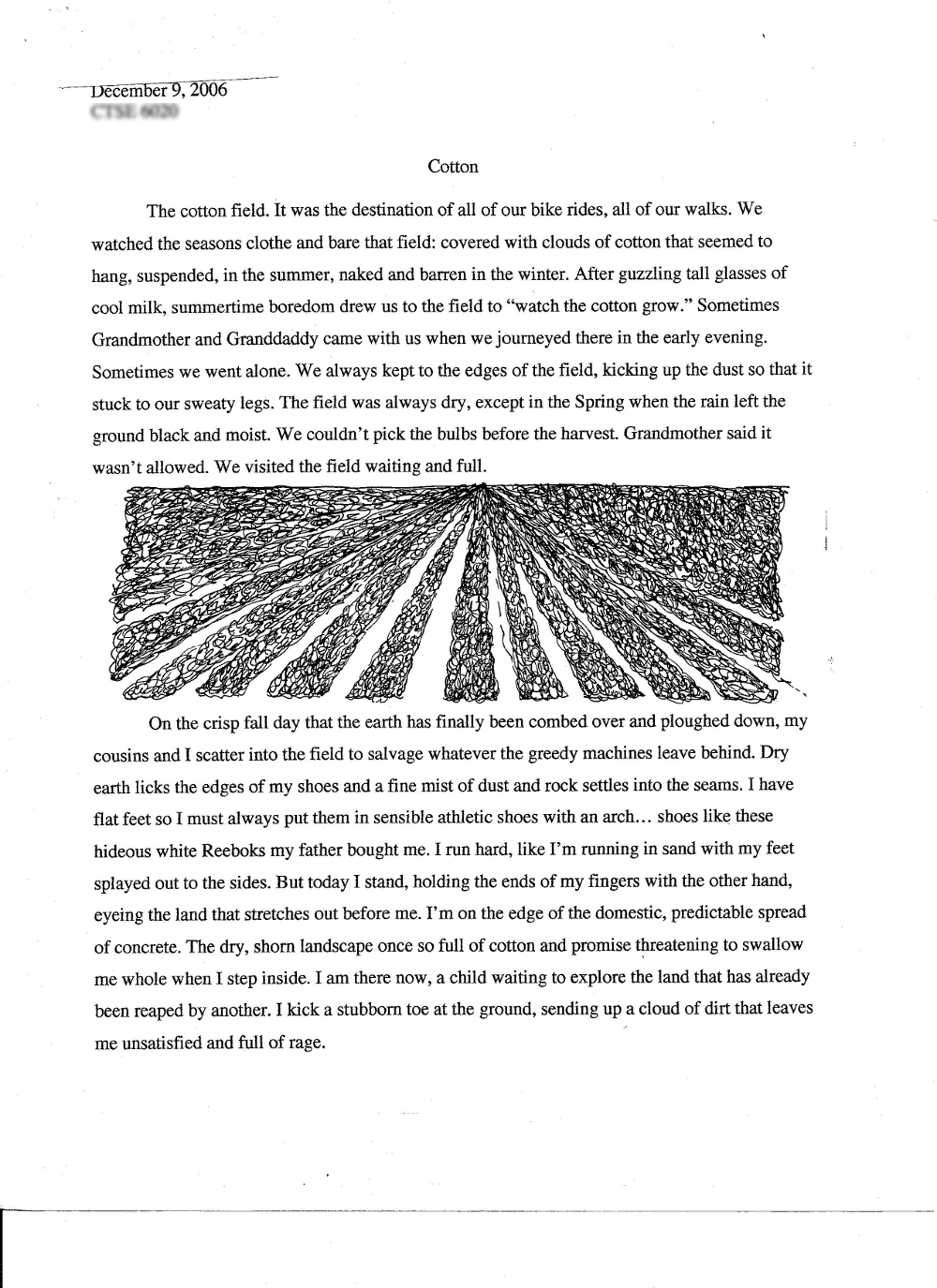

The final version she submitted three weeks later consisted of fourteen different sections of text interspersed with ten different visuals. The pages of the final draft of “Cotton” displayed below show the arrangement of prose vignettes and images that Lindsey settled upon by the end of the semester.

Figures 48–55.

The placement of the texts and visuals in this final version evidences Lindsey’s repeated organizing and re-organizing. Lindsey’s drawing of the rows of the cotton field, which in earlier drafts had been paired with a brief vignette about the grooves that the plows had cut into the ground on page two, had finally found a home on page one where it separated the first two vignettes. The vignette about the grooves had been moved in the final version to page three, where it was paired with Lindsey’s drawing of a car traveling past rows of cotton. Even the brief vignette about trying to plant the cotton seeds, which had appeared at the end of Lindsey’s initial response to the Lost Childhood Places exercise and retained that position in all the successive drafts, had been moved to make place for a new vignette describing a brief interaction between family members at Lindsey’s grandfather’s funeral. What had begun as a few musings about the cotton field near her grandparents’ home had been transformed through Lindsey’s continual arranging and re-arranging based on feedback and suggestions from workshopping sessions into an eloquent pastiche of what Lindsey described in a response to the workshop feedback she received as “different life events that changed my perspective.” Even though Lindsey submitted this version at the close of the semester, her physical manipulation of these elements was far from over. Lindsey continued to use this practice to see and re-see the essay for a number of years as she reworked it for submission to a number of publishing venues, including several anthologies looking for pieces focused on pregnancy.

Lindsey’s ability to envision and enact a workable arrangement for her lyric essay is certainly a socially situated accomplishment. But, in crafting the essay Lindsey recruits the practice she’d used for seeing and organizing literary criticism, a practice which, in turn, she’d deployed for creating visual designs. This discursive practice that Lindsey draws from literature, and from graphic design prior to that, functions as a means of arranging the images and sections of prose into a lyric essay that “works” from the perspective of a creative writer, in a way valued by creative writers. For the lyric essay, the practice functions effectively as a way of allowing Lindsey to make visible and available the vignettes and images she was working with, explore different configurations of those elements, and discover how they might best be arranged into a piece that “works” from the perspective of creative writers. Although the practice had been somewhat “prepared” for use with the lyric essay through its previous uses for graphic design and literary criticism, it is still nonetheless “partial” and thus still requires some restructuring. That restructuring involves resemiotization for use with a multimodal argument comprised of both prose and image as well as being linked with other practices, including generating very early drafts on the computer rather than by hand as she had done for her literary analyses.

Re-situating the Development of Practice (and Person)

Configuring Lindsey’s engagement with this discursive practice in terms of the Composition Approaches for Teachers course, it might appear that her history of development with this practice begins early in the semester as she encountered the “scissors, paper, tape” revision exercise in the course textbook and then continues throughout the semester as she invents and arranges “Cotton.” But, as we’ve seen, Lindsey’s participation with this practice extends far beyond creative writing. In inventing and arranging the lyric essay, Lindsey is acting with a discursive practice that she has re-made and semiotically remediated across a lengthy historical trajectory stretching across a number of engagements. When we see Lindsey’s physical manipulation of the various elements for the “Cotton” essay, we are not just seeing the result of her history of engagement with that discursive practice for creative writing; rather, we are seeing the result of her repurposings and semiotic remediations across doing graphic design, arranging literary analyses, and crafting creative writing. We see, in other words, this practice as it has been elaborated and aggregated for use across these three nexus of practice.

This analysis focuses on Lindsey’s continual remaking of this discursive practice across three disciplinary engagements, but her other uses of this discursive practice have no doubt contributed to its development as well. Noting that “[a]ny action is situated in a life-long historical sequence of acts,” Scollon argues that “at no point could one say that the right bracketing had been done to isolate just those actions in a sequence of actions which would give any one of those actions its meaning” (22). The data collected for this study offered glimpses of some of those other potential uses. Lindsey’s comment about assembling sections of passages and notes for the feminine ideal paper “like a puzzle,” for example, indexes perhaps her use of this discursive practice to solve jigsaw puzzles she encountered as a child and possibly similar kinds of puzzles that she might have been doing with her young daughter. In addition, Lindsey mentioned frequently during our interviews that she had kept a number of different journals (i.e., an autobiographical journal, a prayer journal, a journal of reflections on her teaching, etc.) and that in doing so she frequently cut sections from other documents and taped or glued them onto the pages of those journals. Lindsey also mentioned that she recalled seeing others use their own journals in this manner, including her father and one of her high school classmates. The various “to do” lists and notes Lindsey jotted to herself that Kevin came across as he collected and analyzed texts Lindsey provided for this study suggest further uses of this practice. Those lists and notes frequently referenced textual activities such as paying bills and sending documents to some organization. It is not difficult to imagine Lindsey using some version of this practice as she arranged utility and credit card bills in the order in which they needed to be paid, organized stacks of documents to be sent to insurance agencies, or even ordered and reordered notes regarding household matters on her kitchen counter or bulletin board.

Lindsey’s historical sequence of repurposings of this discursive practice did not end with composing the lyric essay. The very last course Lindsey took to complete the requirements for her Masters in Education in the fall of 2009 was a web design course offered through the university’s Communication department. Talking about the web site she put together for that course during our interviews that semester, Lindsey frequently mentioned the discursive practices she used. She mentioned, for example, how she had employed some strategies for determining perspective to organize information on the opening page of her site:

So, in art and photography, in art, your point of focus should be here, here, or here, and then everything goes out from that point. The other thing is, if you’re going to center something on a page, this is all graphic design, if you’re going to center something on a page, you always drop it lower than the center, because otherwise it looks like its floating. So when I did my website, my page has my buttons here, and this is the picture. (Interview May 13, 2009)

Lindsey also anticipated how her disposition toward physically manipulating texts might inform her future engagements. During her final semester of her MEd program, Lindsey learned that she’d been selected to teach at a junior high school for the following academic year, a school that provided all of its students with laptop computers and encouraged teachers to use them as much as possible. Lindsey stated during one of our interviews that upon receiving the news, one of her first thoughts was that she would “have to learn how to teach all over again because I like to do things by hand” and often incorporated that into her teaching (Interview, May 13, 2009).