The Aesthetics of Protest: Using Image to Change Discourse

Rebecca Jones, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga

Enculturation 6.2 (2009): http://enculturation.net/6.2/jones

The prime difficulty, as we have seen, is that of discovering the means by which a scattered, mobile and manifold public may so recognize itself as to define and express its interest.

John Dewey, The Public and Its Problems

John Dewey’s “prime difficulty” is no less challenging today than it was in 1927. Though we have a vast array of media resources to distribute information, many citizens still find it difficult to actively contribute to public discourse. Here “public discourse” is defined as those discourses that have significant consequences in the life of a citizen: from abortion rights to neighborhood rules. For Dewey, the foundations of democracy rest on resolving this communication dilemma and discovering the means to allow more citizens to contribute to public problem solving. Though American citizens have recourse to political decisions through voting, contacting local officials, and special interest groups, many feel that this system for acknowledging citizen voice is not always the best means to express personal or group interest. Instead, many citizens turn to protest action as means of participation in wider discourses.

There are many theories as to why citizens protest, especially in industrialized nations that support lives of relative ease. Cornel West, in Democracy Matters, argues that an “ugly imperialism” in the United States has contributed to a “massive disaffection of so many voters” (2). West worries that democracy, itself, is in grave danger of being rendered “vacuous” as a consequence of “free market fundamentalism,” “aggressive militarism,” and “escalating authoritarianism” (3-6). Social scientists Dieter Rucht, Ruud Koopmans, and Friedhelm Neidhardt argue that “unintended side-effects of modernization,” such as the impact of technology on the environment, increased education and awareness of inequality, and the “modern interventionist state,” have heightened our sense of dissatisfaction and have led to increased protest activity (7-9). These changes in our political culture, especially impersonal technologies, militarism, and authoritarianism, compound Dewey’s “prime difficulty” as they create an environment where active communication is hindered and attention to individual experience, emotion, and real bodies becomes a secondary concern for public institutions. [1]

As a response to these disaffections and dissatisfactions, alternative politics have increased in new and sometimes unfamiliar forms (see Norris, Aminzade et al., and Meyer and Tarrow). David Meyer begins The Politics of Protest with the following sentence: “Protest is everywhere in American Politics” (1). Pippa Norris, in her third book in a trilogy that examines contemporary protest, argues that “Protest politics did not disappear with afghan bags, patchouli oil, and tie-dyed T-shirts in the sixties; instead . . . political energies have diversified and flowed through alternative tributaries, rather than simply ebbing away” (4). These “alternative tributaries” include not only websites, Internet petitions, and online protest organizations but also public art projects, performances, and image events. More traditional media venues like television and newspapers are often used to launch extensive protest campaigns that can reach vast audiences. Even marches and demonstrations require photographic images to gain media recognition in order to enter public discourse. In Image Politics: The New Rhetoric of Environmental Activism, Kevin Michael DeLuca describes the use of the image event as a rhetorical tactic that transformed the environmental movement. Though protest, as a form of communication, is often considered “extraordinary” (Euchner), or outside of ordinary discourse, it is beginning to be considered a normal component of democracy (Giugni xii). These venues for expressing protest rely largely on images to convey ideas. To this end, it is important to understand why and how activists use image as a means to contribute to the democratic process. [2]

The use of images by contemporary protesters can, most simply, be attributed to a culture awash in images. In describing a new metaphor for the public sphere, DeLuca and Jennifer Peeples offer the “public screen” (literally the T.V. or internet screen): “a discourse dominated by images, not words, a visual rhetoric” (134). W.J.T. Mitchell argues, in his now familiar book Picture Theory, that our culture has taken the “pictorial turn” in which image serves as a provocative mode of communication. [3] Mark Taylor and Esa Saarinen continue this line of thought in their book Imagologies: Media Philosophy as they argue that “In our era, we must philosophize with images rather than concepts” (“Philosophy” 15). Though Mitchell clearly articulates the “pictorial turn,” he is uncomfortable with this shift: in this post-modern world consumed by images “we still have the age-old fear of the image taking over the maker” (Mitchell 15). Social theorist Guy-Ernest Debord, in the late 1960’s, argued that we had entered not simply a culture that uses image to communicate but a culture of spectacle. In this culture, images have been commodified and the public assumes the role of spectator and consumer rather than active agent in the discourses that affect the life of a citizen: “In societies where modern conditions of production prevail, all of life presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has moved away into representation” (Debord The Society of Spectacle 1). In this scenario, images are no longer related to real experience but distanced from experience and manipulated to serve as propaganda to manipulate the masses. Mark Taylor, in an interview with Seulemonde, rearticulates these fears but also recommends a remedy:

Worlds are being transformed by images—and these transformations are going to take place regardless of whether or not cultural critics are involved with them. The challenge, therefore, is to find ways to intervene in the processes of cultural transformation and thereby not to leave everything to the multi-national corporations and governmental agencies. (par. 23)

Like Taylor, Debord offers a solution to the predicament we face in being controlled by the images we consume. He describes détournement as a tool for actively transforming the art images of spectacle into conversations of protest. Instead of passive spectators of propaganda created by corporations and governments, Debord and the Situationists advocate a retaliatory propaganda where the proletariat takes control of the images produced for consumption: “The literary and artistic heritage of humanity should be used for partisan propaganda” (“Methods of Détournement” par. 3). Though Debord and Taylor develop their theories through very different philosophies—Debord from Marxism and Taylor from his work on technology—both recognize the power of images to persuade.

Perhaps, in some ways, we are a culture of spectacle in the midst of a pictorial turn, consuming and being consumed by images. If this is true, contemporary activists answer Taylor’s and Debord’s call to take control of public images. Groups like The Truth and MoveOn have entered the political and social arena through television commercials or print ads, venues primarily used by companies to sell their products. However, the creation of image events and the employment of image as protest are more complex than simply following cultural trends or using the same tools corporations and politicians employ to sell themselves. Instead, this argument pursues the idea that contemporary activists use images precisely because they offer an alternative means to allow their concerns to enter public discourses—especially conversations counter to the discourses that surround capitalism, authoritarianism, or militarism. Particularly, I argue that the use of images and image events offers a more flexible tool than traditional civic participation or even traditional protest practices (marches, petitions, demonstrations, and rallies) for the incorporation of embodied and material discourses and “non-market” values like peace, justice, and caring into larger public discourses on political and social topics (West “Moral Obligations” 5). Through these events, activists draw nearer to realizing a small portion of Dewey’s ideal vision of an equitable democracy where all citizens and their experiences contribute to public discourse and consequential political acts.

Art and the Public Occasion

Image events come in many varieties, from traditional protests staged for translation into mass media distribution to those events that purposefully create art images as a method for communicating dissent. This chapter focuses on the latter—those image events that take the art image as a tool for participating in public discourse. In general, these events offer a response or alternative to “authoritarian” cultures and an attempt to bring private experience into public discourse. More specifically, these events are characterized by a deliberate choice to focus on the visual rather than the verbal/textual as a communicative tool, the use of embodied images, a belief in real experience as evidence, a polyvocal discourse, a grounding in the local and material, and a grassroots online network that disseminates directions and encouragement for creating a similar localized version of the original event.

As a work of art and a public occasion, image events call upon us to consider our beliefs about artists and spaces. We often think of artists as having the ability to capture human emotion and experience in their work and to make us aware of novel ideas and emotions—perhaps to make us aware that new discourses are possible. In fact, Thomas Crow argues that artists often serve as the "avant-garde . . . function[ing] as a kind of research and development arm of the culture industry'" (qtd. in Mitchell 376). For Jasper James in The Art of Moral Protest: Culture, Biography, and Creativity in Social Movements, activists are artists on the "cutting edge of society's understanding of itself as it changes . . . they put into concrete form new ways of seeing and judging the world, new ways of thinking and feeling about it" (13). Similarly, T.V. Reed in The Art of Protest: Culture and Activism from the Civil Rights Movement to the Streets of Seattle finds that in studying social movements through their cultural production, “Movements are at once sites from which particular alternative stories about culture emerge, and a kind of meta-narrative about an alternative way to live in a wider world” (307). As inventors, activists/artists not only attempt to remake cultural conceptions but also the spaces in which they exist. Image events give us a glimpse of activists/artists at work in a public space attempting to transform the “psychogeography” of the space in which they are held (Dubord “Theory of Dérive” par. 3). An event, as a material real-time protest, asks viewers to “inhabit a discourse” unfamiliar to them. Nedra Reynolds, in Geographies of Writing: Inhabiting Places and Encountering Difference, discusses the difficulties of encountering unfamiliar discourses and learning to be comfortable enough to inhabit or dwell within them (165). Though Reynolds’ argument focuses on the unwelcoming discourses we expect students to inhabit in the university classroom, image events attempt to take the discourses already inhabited by activists, victims, survivors, and protesters and make them habitable (at least knowable) for others.

“Airing Your Dirty Laundry”: The Clothesline Project

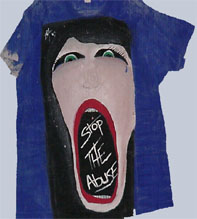

The Clothesline Project, through the language of t-shirts, asks both viewers and participants to try on a discourse about violence. Designed in 1990 by artist Rachel Carey-Harper, the project brings to life an appropriation of the trite saying, "airing your dirty laundry." Literally, the art project is a clothesline hung with t-shirts representing individuals affected by violence. Participants create a visual representation of their experience with violence by painting or drawing on a t-shirt, either on or off site, and then hanging their visual rhetoric alongside others. The one voice becomes many. As a result, the participants not only protest violence, but also benefit from sharing their experience and becoming a part of a community of protesters. The protest is quiet and reflective as participants create and viewers interpret the event in a silent dialogue that holds up a mirror to the silence cloaking domestic violence discourse. This project transfers the private discourse of domestic abuse and violence against women from inside homes to public courtyards, malls, and college campuses. In this public space, the project uses familiar ideas/concepts/images like t-shirts and clotheslines and dirty laundry as an introduction to a new conversation. A neighborhood mall, for instance, becomes a space to discuss violence. Art images of abused bodies communicate individual experience through a community vision. In this particular project, the activists/artists engage in (re)imagining how they are viewed as subjects of public discourse and by the very nature of the “silent” project force viewers to become active participants in the process of change. Though the t-shirts shout out individual protest, as a collection, the Clothesline Project becomes a collaborative art installation that functions as an image event.

As such, The Clothesline Project serves as the model for image events as defined above.  First, these events choose the visual and the embodied as a means of communication. As a discourse about violence done to real bodies that avoids re-vicitimizing those bodies through exposure, the Clothesline Project asks participants to embody the protest through visualizations of their experience: visual rhetorics on a t-shirt[4]. In this way, the deliberate choice to focus on the visual allows the protest participants to protect their real body from public scrutiny while entering a public discourse using their body as evidence in a way that employing only textual discourse could not. Even when the rhetoric on the t-shirts is textual, the choice of font, color, and formation of the letters always offers a visual rhetoric beyond black on white text. This protest speaks directly to the desire to perform the ideal public sphere, a space where citizens come together to communicate and problem solve (DeLuca and Peeples 127-130). The power of the event rests on the visual power of many “bodies” speaking both to each other and to a larger public through image.

First, these events choose the visual and the embodied as a means of communication. As a discourse about violence done to real bodies that avoids re-vicitimizing those bodies through exposure, the Clothesline Project asks participants to embody the protest through visualizations of their experience: visual rhetorics on a t-shirt[4]. In this way, the deliberate choice to focus on the visual allows the protest participants to protect their real body from public scrutiny while entering a public discourse using their body as evidence in a way that employing only textual discourse could not. Even when the rhetoric on the t-shirts is textual, the choice of font, color, and formation of the letters always offers a visual rhetoric beyond black on white text. This protest speaks directly to the desire to perform the ideal public sphere, a space where citizens come together to communicate and problem solve (DeLuca and Peeples 127-130). The power of the event rests on the visual power of many “bodies” speaking both to each other and to a larger public through image.

As these bodies “speak” through art (and often appeals to pathos), rather than depend upon traditional argument strategies or specifically on logical evidence, these images offer experience as the primary evidence for their protest. DeLuca argues that “often, image events revolve around bodies” (10). As such, they offer “body rhetoric” as a “practice of public argumentation” (10). Historically, abused women, especially those abused in private domestic spaces, have little recourse to justice in public institutions or through traditional legal systems or methods of argument. The Clothesline Project depends upon real experience as the primary evidence justifying public protest: the real experience of women and families touched by violence. Their bodies and their emotions are the only evidence they can provide. Though women’s and feminist rhetorics have long valued experience as an epistemology, bodies as evidence, and private voices as subjects for public discourse these concepts are still not the norm of larger public discourses.

Another important aspect of the image events I define here can be heard/seen in the way that individual voices are joined with other individual voices to form not a single “voice” or idea, but a kind of polyvocal display of a general concept. For the Clothesline Project this display is about domestic violence, for the AIDS Quilt the memory of those lost to AIDS, for Women in Black mourning and war. In this kind of event, the focal point constantly jumps from individual t-shirts to the Clothesline Project as a whole. The visual movement reflects a simultaneous valuation of the individual and community experience, from one angry or pained image to an apprehension of the pervasiveness of the problem. In studying one particular Clothesline Project site, the Mid-Michigan Clothesline Project, Laura Julier outlines some common rhetorics found in the t-shirts: “Telling What Happened”; “The Wounded Self”; “Speaking Back”; “Claiming Wholeness”; “Providing Space for Speaking Out” (364-378). These kinds of rhetorical aims do not read like an ideology but a chorus of unique voices making a purposefully dissonant song: “A woman will have complete control over her speaking, its form, its content, its audience, and its purpose, her speaking out will be protected, and her text will join others and will not stand alone” (Julier 364).

Finally, this image event is grounded in the local while also existing as an internet network in a grassroots effort to create multiple sites for the project to exist. While I would argue that most protests have a local and material component, this connection can get lost if and when the protest becomes an ideological campaign. The Clothesline Project avoids the fall into ideology precisely because the project transforms in each location through the efforts and participation of local activists/artists and does not attempt to offer an overarching position concerning violence other than the commonsense notion that it needs to end. Julier argues that “each display circumscribes a place, and thus its text is continually re-created and revised.” The relationship between the activists/artists that creates a T-shirt and the viewer is dependent on the viewer realizing the presence of violence in their midst: a friend or neighbor occupying a T-shirt. Many of the T-shirts have dates, names, and places to mark the violence, to name it and place it. The T-shirts do not represent an abstract idea about violence nor do they offer a lofty theoretical solution. Simply, they represent real bodies of real people that you may have passed in the hall, on the sidewalk, in the mall. This realization is the key to the artistic effort. The project uses an aesthetic appeal to connect “the public” to particular survivors in particular places: violence is happening in this space. The localness of each protest highlights a belief in an experiential epistemic.

While this project began in Cape Cod, most university campuses now sponsor a project at least once a year. Additionally, there are many local women’s centers that sponsor Clothesline Projects and maintain collection of shirts to be displayed. In some cases, the collection can be essentially rented and used as a portable protest event. The Minnesota Coalition for Battered Women Clothesline Project has a website with strict rules about how to request the project and how it is to be used and treated. The rhetoric of the site is similar to the rhetoric of a library or art collection:

We have clotheslines available for exhibit, honoring the women and children murdered as a result of domestic violence, for the years 1992 to 2004. You may request a particular year to display. We will try to accommodate all requests, but may not always be able to provide the clothesline you request. You might want to select a second choice of year. We normally will only lend the Clothesline Project for a period of one week, although we may be able to negotiate a longer display. (par 1)

The national website offers a history of the project as well as connections to local sites, artistic renditions (as shown above), and simple directions for starting your own local project. This includes how to start a project, fundraising ideas, and “how to build a Clothesline Project in 10 easy steps.” The rhetoric found in the directions has been copied and can be found on most websites concerning the event. As such, the projects, though local and changing, do have a consistent look and theme and can be easily recognized as a “Clothesline Project.”

Ironically, the focus of this protest does not seem to be about getting media attention. Few of the websites mention contacting local media when the event occurs, though many of the sites do have links if the local paper picked up the story. It seems that more important than “coverage” is the getting the word out to possible participants. In a way, the creative aspect of the project, the act of protesting, is more important that any overall message about violence.

Seeing AIDS

Many contemporary protests share a similar methodology with The Clothesline Project including the AIDS Quilt and Women in Black events. Like the Clothesline Project both of these image events offer a protest in the form of a collaborative art project. Like the Clothesline Project which takes a “home” discourse and makes it a public discourse, the AIDS Quilt literally brings AIDS “out of the closet” for public discussion. The AIDS Quilt is made of panels created by loved ones and family members of AIDS victims to memorialize their lives while simultaneously giving AIDS a human face. As such, the lives of individual AIDS victims are inscribed as images onto quilt panels. The panels maintain the unique quality of a eulogy with a visual twist. These individual eulogies avoid cacophony through the quilt metaphor that pulls together the images into a familiar symbol of home, love, and comfort: “since quilt making is an art in which one collects, conserves, and orders fragments into a pieced whole, it facilitates the expressions of personal intimacy and political purpose" (Howe).

The disease, AIDS, is very much about real bodies. These diseased bodies, like bodies abused in domestic violence, exist on the periphery of public discourse. Therefore, the foundation of this image event is to make these bodies seen even if it is only through remembrance and memorial. Like the Clothesline Project, this work speaks to the necessity of using experience as argument. In this case, the body is now gone and the panel must serve as embodiment of the lost and evidence of a life.

The Quilt is displayed in public spaces, from the National Mall in Washington D.C., to local churches, schools, convention centers, and auditoriums (Aids Quilt). The magnitude of the AIDS Quilt covering the National Mall persuades through its visual vastness. Whereas the Clothesline Project seems to have an organic existence, popping up wherever a local women’s group takes up the event, the AIDS quilt develops out of organized regions and local chapters. There is an organized clearinghouse for panels at the Names Project in Atlanta which is an official non-governmental organization (NGO). Though the Names Project has larger goals than using the quilt to embody a closeted conversation, the rhetoric concerning the quilt creation and event is very similar to the Clothesline Project in offering simple advice for joining, creating, and participating, easily accessible online.

Visualizing the Effects of War

Women in Black began with Israeli women protesting the violence in Palestine by dressing in clothes of mourning and standing silently on a busy street at the same time each week (Women in Black). Mourning in many cultures symbolizes the lamentation of the dead and is often performed by women. This ritualistic performance becomes an art performance in the service of this protest. Each individual “vigil” allows women to inhabit the discourse of war and conflict, a predominantly male discourse, and transform it through their breach of the space. Women, dressed in black, use the image event as a disruption of the normal visual rhetoric of the space where the event occurs. Unlike the Clothesline Project and the AIDS Quilt, this image event uses real bodies to protest those “bodies” lost in war. As if there are no words to express the pain and grief of war, this event articulates through an artistic rendition of mourning the suffering caused by war.

Like The Clothesline Project and the AIDS Quilt, Women in Black (specifically the Women in Black site) offers clear directions for creating your own image event. The directions after “How to Start Your Own Vigil” begin:

To start a Women in Black vigil, all you need is a commitment to a cause that falls into the category of ‘against war and for justice’. That's the main thing. Below is a description of how many vigils work, but you can establish any formats or rules you like. Remember: every vigil is autonomous. You don't have to ask permission about anything from anybody, other than your own group. (Start)

Whereas the AIDS Quilt is a national grassroots organization, Women in Black offers an international collaboration though it is apparent in the quotation above that each event has a local flavor. In various sites, different acts of violence are protested through the silent black figures lingering on a local street corner. This project takes an additional step beyond the event as various Women in Black groups have organized international conferences and meetings to create a political movement. Despite this difference with the Clothesline Project and the AIDS Quilt, the event itself maintains the local collaboration of individual voices (or bodies in this case) as a means to enter public discourse.

Along with the protest act, Women in Black Art Projects created through art women seem to be a natural consequence of the protest. The project is explained as follows: "The Women in Black Art Project is a feminist cultural activism project that seeks to enhance the visualization and building of peace" (Art Women). As an extension of the protest, feminist artists create mourning costumes worn during these image events. This particular group circulated the costumes and photographs of particular image events in 2002 and 2003 and planned a larger exhibition in 2006 (Gallery). Many of these vigils occur in public spaces of significance to a group promoting peace such as United Nations buildings and Washington D.C.

Leaderless and organic, the Clothesline Project, AIDS Quilt, and Women in Black offer protest that seems to erupt in spaces where verbalizations or texts do not seem adequate for the job. Generally, these three image events initiate new conversations about violence against women, homosexuality, AIDS, and war. These activists attempt to take what many may call “moral issues” and what West names as “non-market values” such as respect for bodies—women’s bodies, abused bodies, homosexual bodies, dead bodies—empathy, love, peace, and community building and create image events that participants hope will spark a new direction in the public discourses surrounding these issues. By creating material manifestations of the discourses they already inhabit, activists, through image events, invite others to inhabit these unfamiliar spaces.

The Discourse of Activism

Activists that stage image events and focus on the image as a tool for expression appear to have similar objectives. One obvious objective is to respond to the kind of culture Cornel West describes by creating discourses that introduce real bodies into public conversation and oppose authoritarian tendencies through community activism. Other objectives include bringing experiences and emotions often considered “private” into a public forum, bridging the ideal and the material, and crisscrossing the divide usually enforced between ideas about the mind and the body. All of these objectives require a different model of public discourse than more traditional conceptions. This model does not focus on persuasion as in many classical rhetorical models (though the events are clearly rhetorical in nature) or work toward consensus and reason as in Jürgen Habermas’s original conception of the public sphere. [5] A more compatible theoretical model can be drawn from discourse studies. Stephen Yarbrough's After Rhetoric: The Study of Discourse Beyond Language and Culture combines the work of the American pragmatists and discourse theorists including Mikhail M. Bakhtin, David Donaldson, and Michael Meyer to yield a theoretical model of human communication with the underlying belief that “Respectful discourse with humans—always ultimately an inquiry into our differences from them—is what makes us human” (15). For Yarbrough, considerations of language and communication in discourse studies differ from similar considerations in rhetoric and philosophy in three ways (46-47): (1) The motivation for communication concerns our differences rather than our similarities; (2) The goal of communication is not to stop talking in the event "truth" is finally discovered, but instead "depends on openness and novelty" (46); (3) Discourse studies understands that the power to persuade should not rely on force but on our ability to "confer credit" to speakers and grant them their own truth: “Its goal is to keep the conversation going, not to silence it, to proliferate differences, not erase them, to respond to challenges, not to submit to them or vanquish them” (47). In general, if you are an activist creating image events you obviously conceive of public discourse as a conversation rather than as ultimatum or mandate or you would not bother trying to make change.

Considering these three differences offers a conception of public discourse that is useful for examining contemporary activism and image events. It is a commonly held notion that in order to have a conversation, participants need to have a shared language, values, etc. (“I can’t talk to her. We have nothing in common.”). However, Yarbrough argues that, in fact, conversation is based on our differences and our desire to understand the other participant in the conversation. The give and take of a conversation happens because we are never completely sure of another person’s meaning and must ask and probe to clarify: “Discourse is motivated by the perception of differences, by disparities between the responses we expect to our utterances and the actual responses we receive” (9). If we truly had to share values and conceptions in order to communicate, then the task of the activist would be impossible considering their message is often counter to commonly held ideas about a particular topic. Likewise, the production of activist discourse would not be necessary if activists did not perceive marked differences between their beliefs and more commonly held ideas. The protest groups I examine here take common material objects and through art offer new metaphorical connections between the object and their own experiences that can yield novel conceptions. Ideally, the new ideas generated by the protest will spark debate and begin to change the discourse on the topic. For example, through the work of feminists and other activists, we now conceive of abused women as survivors rather than victims. As such, our discourse on domestic violence has changed, including our response to it. Nancy Fraser explains that feminists trying to enter the public debate about private issues like domestic abuse were forced to create a "subaltern counter public from which to disseminate a view of domestic violence as a widespread systemic feature of male-dominated societies" (71). Once the counter-discourse was established and after "sustained discursive contestation," the discussion of domestic violence entered other public discourses. Like Fraser, Julier understands that new discourses offered by activists are always different from current discussions of the topic at hand. She explains that the Clothesline Project disrupts “the discursive practices” surrounding domestic violence and “blurs the traditional and expected boundaries between private and public speaking” (360-61). Clearly, activists understand that conversation must be stimulated by difference, disruption, and contestation.

Yarbrough’s second point expresses the notion that conversation should lead to more conversation rather than a final solution. Traditionally, in philosophy, the goal of discourse is to achieve a single conclusion, the one truth that explains the world, human beings, etc. To value contingency and open-ended discussion may seem counterproductive if you conceive of the goal of activism in revolutionary terms—the permanent reversal of ideas and actions. However, the goal of many activists, especially those presented here, is more about awareness, community, and debate. Seeking a permanent solution or a new truth will only require more activist intervention in the future as people and cultures change. Instead, image events like the Clothesline Project ask viewers to “put yourself in my shoes,” “ask more questions,” and “take care of your friends and loved ones.” The AIDS Quilt seems to seek awareness and empathy while Women in Black asks viewers to think about human consequence rather than winning a war. These image events do not present final solutions to domestic violence, AIDS, or war but seek open debate, conversation, and recognition that the solution to these problems will require a community effort, especially from those who hope to ignore the problem or view it as separate from their world or community (outside of their habitual space).

Yarbrough’s final difference acknowledges the difficulties a group will have in entering and changing public discourses. He distinguishes between rhetorical force and discursive power as a way to talk about change in terms of public discourse. Most citizens hope to avoid using real force as a means to express their ideas. To have rhetorical force, for Yarbrough, means others believe you have the real force (whether physical, material, or economic) to act on what you are saying if necessary. However, to have discursive power means that listeners believe you have the power to convince others to believe in and act on your rhetoric, whether or not a particular listener personally believes your rhetoric (28). Having discursive power is about conversing and debating rather than persuading because discursive power implies an audience outside of the one viewer participating in the conversation.

This last conception of discourse is more about an ideal audience than the formation of the discourse itself. Certainly, many activists lack rhetorical force as they usually lack the material or economic force to sway an audience with their ideas. What they need is an image event that is compelling enough for viewers to “confer them credit” that they not only strongly believe in their new ideas but that others will believe in them and, more importantly, act on them as well. If we were all “students of discourse” then the ideal public and its model of public discourse would always involve granting power to the person or group speaking. In granting them power, we begin conversations in a space where we “give them credit, at least provisionally, for being sincere in what they say—credit for articulating real differences” (Yarbrough 33).

The Discourse of Images

If an ideal form of human discourse is to grant others power and to acknowledge difference, meaning different personal, social, and cultural experience, then image events created by activists serve as model for beginning this kind of conversation. The activists discussed here primarily want to infuse public discourse with the experiences and embodied rhetorics of citizens that have not yet contributed or are not able to contribute equitably to public conversation. This task requires a confluence of experience, real bodies, and art.

John Dewey in Art as Experience draws a connection between experience, art, and civilization. Not only does he describe the importance of art to the creation of a culture, but also that experience itself has an aesthetic quality: “Art is a quality that permeates an experience. . . . The material of esthetic experience in being human . . . is social” (326). Here Dewey establishes a link between art, experience, and public discourse, i.e. the social. Dewey objects to the sequestering of art into museums because it creates a false separation between the art itself and the material conditions of its creation. To think seriously about a philosophy of art, the “task is to restore continuity between the refined and intensified forms of experience that are works of art and the everyday events, doings, and suffering that are universally recognized to constitute experience” (3). Art should not merely be considered “self expression” but an expression of one’s collective experience within a particular culture. Dewey works in this text to advocate a deeper appreciation of the aesthetic in everyday workings of the world because once we regain this appreciation we will become more active participants in the evaluation of our experiences. Just as we must engage in a piece of art, we need to learn to engage in an understanding of our experience—both mind and body (5). It is the artist that can most easily acknowledge the aesthetics of the everyday and translate them into art images that can achieve activist goals. Cornel West explains, “it has been primarily artistic, activist, and intellectual voices from outside the political and economic establishments who have offered the most penetrating insights and energizing visions and have pushed the development of the American democratic project” (Democracy Matters 102). The image event offers the tools for expressing “penetrating insights” of embodied discourses precisely because it is art.

Anna West, an art student from Carlow University who helped to create a local Clothesline Project explains, “Art is communication that doesn’t need words to express emotions. Art comes from the heart and communicates to the heart through imagery” (qtd. Ruhe 22). This student’s belief offers a commonly held notion about the power of the Clothesline Project and about art in general. Somehow the art image seems to “speak to” people in ways that words alone cannot. Perhaps the reason we sometimes conceive of images as being more powerful than words comes from our visual perceptions of the world that precede language.

In philosopher Susanne Langer's Feeling and Form: A Theory of Art, she claims that images make up the root of our thought processes: "the basic symbols of human thought are images" (376). Perhaps this is why the image seems to be able to connect to an audience in a way words sometimes cannot. These images, in turn, can connect directly to our emotions:

A work of art, or anything that affects us as art does, may be said to "do something to us," though not in the usual sense which aestheticians rightly deny—giving us emotions and moods. What it does to us is to formulate our conceptions of feeling and our conceptions of visual, factual, and audible reality together. It gives us forms of imagination and forms of feeling, inseparably; that is to say, it clarifies and organizes intuition itself. (397)

It is those aspects of human experience more closely related to our conceptions of “feelings” that the image event attempts to incorporate into a public conversation. Langer's general philosophy offers a theory of the mind that advocates feeling as the basis of human thought rather than logic. Rather than focusing on either feeling or logic, Langer sees the two as intimately woven together. A more common metaphorical construction of the mind is “mind as machine” where the human mind processes and spits out information reasonably and logically and must control the emotional and illogical impulses of the body. This more Platonic notion of the mind/body divide has been disputed and revised in most fields of study, yet the notion persists. Against this conception, Langer posits a mind that is more closely associated with conceptions of the body. Langer describes her process of discovering these ideas as follows:

It was the discovery that works of art are images of the forms of feeling, and that their expressiveness can rise to the presentation of all aspects of mind and human personality, which led me to the present undertaking of constructing a biological theory of feeling that should logically lead to an adequate concept of mind. (Mind xviii)

Langer's project seeks a philosophical description of the mind that demonstrates the primacy of material experience and human emotion for mental processes. Langer feels we need to learn to read the "forms of feeling" captured by art images in philosophical ways as a means to "see new forms of vital experience" as they emerge (Mind xix). This means that "logical" human thought is always shot through with both material existence and human emotion, no matter how much we attempt to divorce reason and emotion. Langer’s philosophy helps to articulate the problem of presenting bodies in public discourse when this space traditionally is held open only for logical discourses of the mind. DeLuca explains, "There are no a priori bodies. Bodies are enmeshed in a turbulent stream of multiple and conflictual discourses that shape what they mean in particular contexts" (DeLuca 12). To present the material experience of the body, we need to define public discourse as a space without boundaries between emotion and logic, bodies and mind. Ironically, Taylor and Saarinen explain that "Since image has displaced print as the primary medium for discourse, the public use of reason can no longer be limited to print culture" (Taylor and Saarinen 4). So, to discourse through image means to offer a logic of experience as an alternative discourse. For example, the Clothesline Project creates a discourse of domestic abuse that recognizes the range of emotion experienced by abused bodies and offers a community of hope to survivors. This discourse offers an alternative to legal discourses of abuse that focus on the abstract and disembodied language of rights and protections.

On the other hand, in Philosophy in a New Key, Langer acknowledges that many appeals to the material attempt to reject the symbolic and focus solely on the “reality” of experience. Instead, Langer emphasizes the fact that humans yearn for symbolic creation. Langer believes that the creation of symbol and ritual are a sign of healthy living:

A mind that is oriented, no matter by what conscious or unconscious symbols, in material and social realities, can function freely and confidently even under great pressure of circumstance and in the face of hard problems. Its life is a smooth and skillful shuttling to and fro between sign-functions and symbolic functions, a steady interweaving of sensory interpretations, linguistic responses, inferences, memories, imaginative prevision, factual knowledge, and tacit appreciation. (Philosophy 289)

In a world often characterized by the white noise of Don DeLillo's novel of the same name—an endless droning monotony of work, television, and consumerism—artistic image events are a welcome relief. From Langer's perspective, imaginative and symbolic protest shows a healthy mental state that reminds society of the natural connection between public discourse and human experience.

In the opening quotation, Dewey presents a dilemma—how do we talk to each other as responsible citizens in a world where citizens are dispersed and consequently experiencing different kinds of lives? Activists, through image events, extend the question to ask, how can we talk about experience, emotion, and real bodies in a public space? Though image events do not solve this dilemma, they do offer a space to test one kind of coming together.

Examining image events yields a portrait of both the creator and viewer of activist discourses. As creators, activists demonstrate a valuation of real bodies, their emotions, and experiences as an important component of public discourse on a variety of social and political topics. Through image events, activists advocate a model of public discourse that encourages conversation rather than an end game solution. Their use of images to discourse with others shows an attempt to connect with a viewer’s own body, emotions, and intuitions as a method of conversing rather than appealing only to logic. Though Aristotle offered an extended list of the ways to connect to various audiences through their emotions, his purpose was persuasion rather than conversation. From the perspective of the viewer, an image event asks for engagement, personal connection, and in the end, effort. As activists hope to spark engagement, they ask the viewer to reconsider the way public discourse works and hope that they will acknowledge their discursive power rather than only engaging with rhetorics of force.

Cornel West believes we are yearning for this kind of discursive engagement. Though he acknowledges that many citizens have rejected traditional political engagement due to a “lack of authenticity of discourse,” West admits that the “disgust so many feel comes from a deep desire to hear more authentic expressions of insights about our lives and more genuine commitments to improving them” (Democracy Matters 64). Though image events are not the ultimate solution to a culture of disembodiment and rampant consumerism, they can serve as a model for new ways of making connections and starting conversations that have the potential to make real change.

Works Cited

Aminzade, Ronald, ed. Silence and Voice in the Study of Contentious Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Artwomen.org. “Women in Black Art Project.” 4 Nov. 2005. http://www.artwomen.org/wib/wibmain.htm

Coen, Noam. “Moldovans Turn to Twitter to Organize Protest.” The Lede. New York Times. April 7, 2009.

Debord, Guy-Ernest. The Society of Spectacle. Black and White. 2001. 4 Nov. 2005 http://library.nothingness.org/articles/SI/all/pub_info/4

___ . “Methods of Détournement.” Black and White. 2001. 4 Nov. 2005. http://library.nothingness.org/articles/SI/en/display_printable/3

___ . “Theory of Dérive.” Black and White. 2001. 4 Nov. 2005. http://library.nothingness.org/articles/SI/en/display/314

Deluca, Kevin Michael. Image Politics: The New Rhetoric of Environmental Activism. New York: The Guilford Press, 1999.

___ . "Unruly Arguments: The Body Rhetoric of Earth First!, Act Up, and Queer Nation." Argumentation and Advocacy 36 (1999): 9-21.

Deluca, Kevin Michael and Jennifer Peeples. "From Public Sphere to Public Screen: Democracy, Activism, and the "Violence" of Seattle." Critical Studies in Media Communication 19.2 (2002): 125-51.

Dewey, John. The Philosophy of John Dewey. Ed. John McDermott. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981.

Euchner, Charles. Extraordinary Politics: How Protest and Dissent are Changing American Democracy. Boulder: Westview Press, 1996.

Fraser, Nancy. "Pragmatism, Feminism, and the Linguistic Turn." Feminist Contentions: A Philosophical Exchange. New York: Routledge, 1995.

Giugni, Marco, Doug McAdam, and Charles Tilly. From Contention to Democracy. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 1998.

Habermas, Jurgen. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Trans. Thomas Burger and Fredrick Lawrence. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1999.

Howe, Lawrence. "The AIDS Quilt and Its Traditions." College Literature 24.2 (year?): 109-124.

Jasper, James. The Art of Moral Protest: Culture, Biography, and Creativity in Social Movements. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

Julier, Laura. "Voices From the Line: The Clothesline Project as a Healing Text." Writing and Healing: Toward an Informed Practice. Eds. Charles Anderson and Marian MacCurdy. Urbana: National Council of Teachers of English, 2000.

Langer, Suzanne. Feeling and Form: A Theory of Art. New York: Charles Scribner's and Sons, 1953.

___ . Mind: An Essay on Human Feeling. Volume I Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1967.

___ . Philosophy in a New Key: A Study in the Symbolism of Reason, Rite, and Art. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1957.

Meyer, David S. The Politics of Protest: Social Movements in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Meyer, David S. and Sidney Tarrow. "A Movement Society: Contentious Politics for a New Century." The Social Movement Society: Contentious Politics for a New Century. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc., 1998.

Mitchell, W.J.T. Picture Theory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

Patterson, Thomas. The Vanishing Voter: Public Involvement in an Age of Uncertainty. New York: Knopf, 2002.

Norris, Pippa. Democratic Phoenix: Reinventing Political Activism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Phillips, Kendall R. "The Spaces of Public Dissension: Reconsidering the Public Sphere." Communication Monographs 63 (1996): 231-248.

Reed, T.V. The Art of Protest: Culture and Activism from the Civil Rights Movement to the Streets of Seattle. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005.

Rorty, Richard. The Consequences of Pragmatism (Essays: 1972-1980). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1982.

Rucht, Dieter, Ruud Koopmans, and Friedhelm Neidhardt, eds. Introduction. Acts of dissent: New Developments in the Study of Protest. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 1999.

Ruhe, Bethany. “Speaking Up Through Art.” The Carlow Journal (January 2005):

Taylor, Mark. The Moment of Complexity: Emerging Network Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Taylor, Mark and Esa Saarinen. Imagologies: Media Philosophy. London: Routledge, 1994.

West, Cornel. Democracy Matters: Winning the Fight Against Imperialism. New York: The Penguin Press, 2004.

___ . “The Moral Obligations of Living in a Democratic Society.” Good Citizen. Ed. David Batstone and Eduardo Mendieta. New York: Routledge, 1999.

Women in Black. “Women in Black. For Justice. Against War.” 12 March 2006. http://www.womeninblack.org/index.html.

Women in Black. “Our Mission.” 12 March 2006. http://www.womeninblack.net/mission.html. 11 November 2002.

Yarbrough, Stephen. After Rhetoric: The Study of Discourse Beyond Language and Culture. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1999.

[1] In the reference to “impersonal technologies,” Dieter Rucht, Ruud Koopmans, and Friedhelm Neidhardt are discussing technologies like television which do not normally allow an audience to interface with the discussion at hand or governmental technologies that garner information about citizens without their knowledge. This is not a reference to newer technologies like internet, cell phones, or twitter that have contributed to the success of many recent protests. One example can be found in an April 7, 2009 New York Times article by Noam Coen titled: “Moldovans Turn to Twitter to Organize Protests.”

[2] Democracy is defined in Deweyian terms for this paper as a social idea. Dewey distinguishes, in "Search for a Great Community," between "democracy as a social idea and political democracy as a system of government" (621). As an idea, democracy is "the name for a life of free and enriching communion" (643). As a political system, Dewey explains there is no "sanctity" in the form of democracy we have in America (621). According to this definition, using image to communicate protest is not an unusual form of communication but simply another tool used for contributing to democratic processes.

[3] Mitchell opposes the “pictorial turn” to the “linguistic turn” that Richard Rorty describes as taking place with regard to recent theory in the humanities.

[4] The following is an excerpt of artist Lori Estomin’s statement about her art work titled “The Clothesline Project”:

The images in “The Clothesline Project” were photographed in Washington D.C. on April 9, 1995 during the March for Women’s Lives. Unlike the AIDS Quilt, which lies flat so viewers are immediately struck by its size and the vast number of lives lost, the clotheslines snake back and forth, making it impossible to see all 6000 shirts at once. Like domestic violence, much of the display is invisible. I chose to layer some of the images in this series to give a better sense of the emotional impact of walking between row after row of individual women’s stories and to give the white shirts (representing women & children killed by domestic violence) as a ghostlike presence.

This artistic rendition of the Clothesline Project does an excellent job of capturing the levels of artistic interpretation required of the audience by simultaneously emphasizing the individual and the community.

[5] The desire for consensus inherent in the concept of the "public sphere" no longer reflects the realities of "new forms of participatory democracy" (DeLuca and Peeples 125). Kendall Phillips's decentering of the public sphere in "The Spaces of Public Dissension: Reconsidering the Public Sphere" as a space for creating consensus opens up possibilities for multiple points of dissent. To define a public sphere means there are other "spheres" different (less valued) from this ideal space. Phillips defines six aspects of the public sphere that presuppose its rational, coherent, and consensual nature (237). These ideals actually limit participation rather than aid in the establishment of "true" public opinion. More importantly, the ideal public sphere viewed as a "cure" for "dissension" limits protest rhetoric to a "disruption in the normal process of the creation of a functioning public sphere" (Phillips 243).