Jane Slemon, Emily Carr University

Enculturation: http://www.enculturation.net/playful-display

(Published December 21, 2011)

finally free, slid as snake from

his own sweet agonized skin, to throw his entrails

white upon the floor with a cry of victory—

now there are no bonds except the flesh

—Gwendolyn MacEwen “Manzini: Escape Artist” 471

white upon the floor with a cry of victory—

now there are no bonds except the flesh

—Gwendolyn MacEwen “Manzini: Escape Artist” 471

—Gwendolyn MacEwen “Manzini: Escape Artist” 471

Stepping across the threshold of the Body Worlds gallery feels like spelunking—all the noises of the city drop to a palpable hush. Human forms set playfully (might we even say eagerly?) on plinths welcome us into some timeless space—a place without history or even the language to describe what we cannot account for, without buttons or mobile connections: here is the anatomical form, relieved of skin and story, unhinged from politics and because of its plastinated form now even released from the passage of time. The billboards of the city have let us know of this must-see event (see Figures 1 and 5). Friends carry an amazed look when they mention it, unable to quite explain what gives them pause about the exhibit. And this is how we (and busloads of school kids) are drawn toward a traveling road show, an art gallery and a science display, all in one exhibit. These familiar, these bodies “finally free” of “agonized skin,” teach us who we are “feelingly,” as blind Gloucester says, though the irony is they’ll never feel again, and our strategy for handling the experience of roaming amid the previously alive is to imagine we feel at home with them (MacEwen 471; Shakespeare IV.v.151).

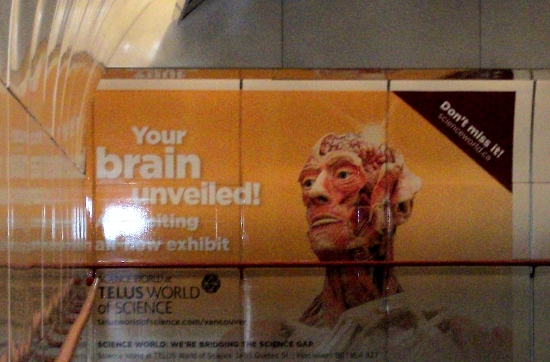

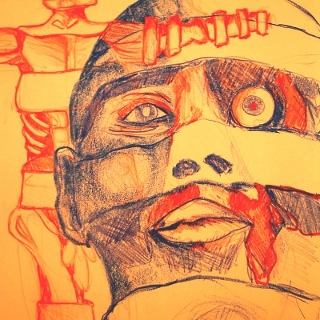

Taking my science students to see Body Worlds: Exploration of the Mind, our purpose was to draw, since Leonardo da Vinci taught us by drawing to see, by seeing to know, and by these to question and correct assumed knowledge (a few of their drawings are offered in Figures 3, 4 & 6). But in the gallery, a complex set of manipulations is at work that invites a McLuhanesque examination of the new cadaver. Is it ourselves, pared down to nerve and bone, that is the present spectacle or is it the art and science of plastination we have come to see?

Figure 1. Billboard for Body Worlds: Exploration of the Mind

at Stadium Skytrain Station. 14 May 2011. Vancouver, Canada.

Photo: Slemon

Plastination, developed for use with human tissue in Germany by Gunther von Hagens, is the invisible technology that shifts the cadaver from the more rarified laboratory of the medical school into art form. Even though we somehow know not to actually touch the cadavers, what could be more “tribal and ear-oriented,” more unifying than this “space of touch” (McLuhan From Cliché 83)? Body Worlds is a tactile space, and we the moving objects that complete the exhibit. The figure of the The Thinker exposes brain, spinal cord and nerves, its pose Rodinesque (see Figure 2); a female figure is cut on a ventral plane from head to abdomen such that she appears, from an angle, to be entering herself from behind; and a male figure, sliced on the sagittal plane, suggests an accordion of connective tissues. We are understandably a little dizzy before these stiffly transformed because of a swift shift in figure and ground. “What ever [the viewer] does not see”—and thus what we are less critically aware of—“is the ground,” says McLuhan’s biographer, Philip Marchand (248). In a gallery space, the ground is usually the viewer; yet, these figures comment on our very being, as living beings and as eventually dead ones.

The chatter and the beeps of the transit systems we have employed to bring us to Body Worlds are muffled as we drift past the light-absorbing ceiling-high black curtains. Enfolded into the gallery space, we are twice protected from any symbols of race, history and politics: these curtains and these bodies “free of agonized skin” give us the first and seemingly final cliché—the body neutral (MacEwen 471). Silent, uncritical and reverent, we perceive a kind of blank canvas, a flabby metaphor any member of the public can fill in; we recall associations with our own dead, with spiritual notions of where the body and soul go after death, and with high school lessons on the human machine. Sections of the tossed mortal coil are the ticket items of the day. These cadavers seem to be having fun, and we viewers are stiffly serious, living examples of the heart and brain cross-sections we gaze upon. Quiet forms on plinths adopt both the most humble and most extravagant of stances possible: that of being at once unidentifiable and and iconic rock stars.

Figure 3. “The Nervous System, drawn at Body Worlds.”

Hailey Whitt.

2010. Slemon’s Science 201. Emily Carr University.

When that doubling occurs, Marshall McLuhan appears.

Oh that this too melted flesh would solidify.

Figure 4. “The Femur, drawn at Body Worlds.”

Carolina Perez.

2010. Slemon’s Science 201. Emily Carr University.

A cliché, the body is “tossed aside,” states our McLuhan to one of the white-lab-coated volunteers; this art form, he continues, “is a cliché probe that scraps older environments”—environments such as, say, having a life, and these cadavers “scrap” life (From Cliché 149). We learned from the television show Survivor and its central premise (If I were on a desert island with you and only a few other people...) that the dead metaphor, the archetype, and cliché are just what we yearn for. Our attention moves toward the shift of ground into figure; we love to recognize, to notice the echo of a previous icon, and to see old things anew. In From Cliché to Archetype, McLuhan’s notion that the object given new context is drawn out of cliché—out of an environment so familiar that we no longer sense its presence—is the tool Body Worlds uses to toy with us. Viewers of the plastination phenomenon are rendered at once spectacle and examiner. We are what we came to see, posed on the plinths as skateboard adventure seekers and figure skaters in unlikely balances pared down to bone.

Like a fragment of one’s own life newly re/membered, the show strikes us as already a part of us. No wonder we are drawn in with a curiosity usually reserved for the “rag and bone shop” this time quite literally “of the heart” (Yeats qtd. in McLuhan From Cliché 20).

Today’s cadaver observes us, smears us.

Marshall McLuhan warned us the narrative of technological and global progress would arc towards a discarnate state of being, would force our senses out of our bodies toward an “electric all-at-onceness” (McLuhan & Zingrove 5). The fully discarnate human, whose soul is everywhere at once, has let technology extend each of our human senses out to “probe and shape the physical environment” (McLuhan, From Cliché 150). “As [each] new technology is interiorized,” says McLuhan, our very “culture” is further “translate[d]” (McLuhan Gutenberg Galaxy 40). If we weren’t so shy before these figures, we’d get the joke more quickly. Having stepped into a world of sinew and cell, before this awesome trick of nature that we have no artists or designer’s claim to, we seem to have returned to a world wherein even McLuhan might be silent. I can hear my heart beat; I feel what I see. Certainly, I’m thinking, this is the place without buttons, where sense is returned to the body. But, no, McLuhan isn’t silent. Too loudly, he says something about dead metaphors, then steams on to see the rest, already understanding.

Plastination’s new application to animal tissue at Body Worlds is combined with a current lust for reality TV; simply breathing in this room, we participate in the activity of indeed the deadest of metaphors, the cadaver spun as cliché, sharpened to probe. Would McLuhan consider this a turning off or on of the buttons? We participate deeply: we consider, as we walk through, our notions of our own life’s ending, whether we’ll ask to be buried, burned, donated. The question has never been so wholly synesthetic, engaging of our whole human sensorium. Having circled the room, McLuhan taps us on the shoulder and reports that we are acting the way the manufacturers want; we are submitting to a spanking new maelstrom without realizing the moment of consent has already passed. Before we can shake him off or comprehend what he means, he reminds us we are distracted from the larger picture: in Body Worlds (“Isn’t the title rather an echo of the global village? Is there someone I can talk to about that?”), the advertiser takes up an artist’s “palate” dripping with our very emotions, his “private pigment,” and “smears us” (McLuhan qtd. in Tom Wolfe).

The technology of plastination extends not the sense of being dead

but a post sense. Human/Post. Regard the posthuman.

Posthumanism’s point, according to Cary Wolfe’s What is Posthumanism, is that humans can no longer imagine themselves as occupying the mid-point between molecules and galaxies; in other words, humans aren’t the cosmic centre and are not specially placed between planets revolving around their suns and electrons circling their nuclei like little planets themselves (according to Hantaro Nagaoka’s 1904 image of the atom). Relegated to the past century now is the notion that inside each sperm hides a potential human, a homunculus (although this word survives in medical language to describe the selves we sense in order to understand our position in space). Wolfe’s definition of posthumanism notes that as “fellow creatures” of a mortal nature, humans “enter into contractual agreements or reciprocal behaviors” which allow them “an ethical divide between Homo sapiens and everything (or everyone) else” (Cary Wolfe 62).

Wolfe points out that theorists like Jacques Derrida identify an “evolutionary and adaptive problem” of being human while also addressing the “overwhelming environmental complexit[ies]”of being human (xxvi). “Only in a refus[al] to locate meaning in the realm of the human or, for that matter, the biological,” it seems, can we shake out new solutions to support a more just and ethical relationship to the world and to non-humans (xxvi). Similarly, Donna Haraway’s notion of the cyborg—as liberating individuals from gender and biopolitics—challenges us to find fresh meaning in the non-living, perhaps even to the point of including the cadaver’s very structures, substances and sinews evolution has slowly given rise to. As we gaze at the marvelous human machine, we experience the dangers of human organicism, as if animals, other forms of life, and all substances and entities respond to and support a human organic centricity.

Figure 5. Billboard for Body Worlds: Exploration of the Mind

at Granville Skytrain Station, Vancouver, Canada, 2011.

Photo: Slemon

After its controversial first exhibit closed in Munich in 2003 (because, in a Catch 22 of legalities and protocols, the origin of cadavers could not be confirmed since von Hagens committed to a rigorous “body-donor programme” of his own making that obscured the tracing of individual identities), Body Worlds II incorporated into the show a framed consent form revealing how bodies are donated (von Hagens). At Body Worlds, we are part of an historical shift in the cadaver’s moment on the stage.

Three huge shifts in the cadaver’s audience have occurred in the past 500 years. When Leonardo da Vinci drew illustrations and generated writings from 30 or so cadavers in 1510, creating his astonishing Anatomica Manuscript A, almost no one saw the works for 122 years—and then only a part of it was published in France. “Cadavers they may be but since we perceive them as being in use, working from the inside out,” each illustration “reveals what it is we know by way of sensation” (Slemon). Leonardo’s connection to physician Marcantonio della Torre secured him that rare chance to work with cadavers at the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova. As well, Vesalius published his De humani corporis fabrica in Italian (1547) rather than in Latin, giving rise to a far larger audience than had previous enjoyed access to human anatomy. Finally, Body Worlds has increased the audience of the cadaver, and we are alive to pay (not tuition fees but a moderately hefty ticket price) and play along.

The new media are not bridges between man and nature: they are nature.

—McLuhan “Where the Hand of Man Never Set Foot,” Hot and Cool 116

What separates the organic system from media and technology? Bernard Steigler offers that “technics” and “metaphysics” are a false opposition, a binary that can be collapsed by acknowledging the “problem of the nature of the human,” which is to say the problem of “human origin” (Steigler 95). We can then discern what we have also thought to be vagrant, or “accidental,” that is, what lies within the range of natural possibilities for human evolution, by admitting that many people still locate the special nature of humans in their origin and enter “the question of being” within this assumption (95). If, as we stand before the previously dead, unaware of skin colours, tattoos, or wrinkles that would have ushered in our habitual and sweeping generalizations of identity, we are brought into Steigler’s question of being since “the principles of being are those of reasoning, and only reasoning allows any trace, whatever its age, to be deciphered” (96).

This is what the gallery room’s sanctuary and reverence are about—we reason the existence of a “trace”—an “enigma of origin” (96). We can’t help but marvel that we evolved to this. And Steigler supports the idea that technology and nature are neither separate nor bridged: he suggests that, if we trace a line from origin to some notion of a fall, then that fall must be conceived of: perhaps the image is of planets and a gravitational pull toward the elements of earth, water, air and fire; or perhaps it consists of a host of interconnected myths, heavens and powerful gods: this, says Steigler, is “a fall into technics” (96). Whatever the image is, it is not what is—rather, it is a covering over, a “contingency,” and thus, he states, “to fall is to forget” and to shift into metaphor (96).

Forgetting old notions of a comfortable distance between the human soul (which might be defined as being “intelligible and sensible”) and technics (which “does not have the principle of its movement in itself”), we might recognize that technics too traces back to an origin, a conception, a being (96). All technics also play out possibilities and roles, relationships and interconnections, their evolutions tracing back to original beginnings, not “separate and not bridged” (Steigler 96). From beyond the pale, McLuhan tells us these playful cadavers of the new millennia are “not bridges between man and nature: they are nature” (McLuhan 116).

Today’s cadaver is dashingly

medium and message.

Figure 6. “Brain, bone and skin, drawn at Body Worlds."

Theunis Snyman.

2010. Slemon’s Science 201. Emily Carr University.

From Dr. Frankenstein in his laboratory to the classrooms of medical students, our image of the cadaver enjoys a range of roles, from gruesome to respectful. In anatomy classes, perhaps four students to a cadaver, students are honored to engage in a practice they know was banned for more than a thousand years, since Galen’s experiments in anatomy. Students chat in low tones and discover the intricacies of organs and tendons, noting the clues about an individual’s lifestyle, the strains and scars written in the tissue. My parents’ intention to donate their bodies to The University of Toronto for medical and educational use is rooted both in their dedication to education and science and in their memory that my Great Uncle Charnock Matheson always lacked sufficient numbers of cadavers, at Queen’s University in Kingston, for his anatomy classes in the 1930s and 40s. Body Worlds doesn’t represent the same notion of educational use as the medical classroom. Still, times have changed from the days of Vesalius and his colleagues obtaining cadavers from unconsenting individuals; as Katherine Park points out in Secrets of Women: Gender, Generation, and the Origins of Human Dissection, bodies were often those of “criminal[s]” and women (such as is depicted on his title page) (214). Today, Gunther von Hagens has plenty of donations for display, but those donating sign away their control over how they’ll be shown, for how long, how much of their bodies will be used, or the age, education level and reverence of the viewer.

Anything goes; anyone comes.

At Body Worlds, because exposed organs, splayed muscle and bone—part of us all the time and for which most of us can little account—are balanced and posed for play, we too are part of the show as we circulate about the gallery. In “Inside the Five Sense Sensorium,” McLuhan offers an apt analogy for the effect of our movement when he says the “mosaic mesh of luminous points” of the television effect us in ways akin to a Seurat pointillist painting that, by its low definition, “elicits high empathy or participation” for viewers (McLuhan “Inside” 44). When moving points are part of the effect, viewers together form a cool medium—an “oral-aural world” not characterized by the detachment particular to the “visual-literate” world (45). Just as with a painting or television, there exists in a Body Worlds gallery plenty to look at, but focus is not the point. Part of the effect is that viewers experience and accommodate what they imagine is the heightened sensitivity of all other viewers in the room. Part of our baggage is a natural or cultural resistance to the idea of being dead. Funereal thoughts, scientific fascination and flighty associations all force our gaze past the figures, almost as soon as we have looked at them, to consider the abstract concepts of the body. We look, but only briefly, and let our thoughts slide toward a host of deep thoughts and abstractions.

McLuhan himself is a fine example of resistance to peering at human tissue: When told of his own brain tumor, in 1967, and of the operation he would have to endure to have it removed, McLuhan declined any and all “details of the operation,” saying that “anything that would enable him to visualize the workings of the surgeon’s knife” was to be kept from him (Marchand 201). While we take comfort in seeing human anatomy as quite marvelous, treating these cadavers as mere shadows of an ideal, McLuhan’s inclination to shrink from specifics of his own flesh is perhaps typical: just as the highly involving medium of TV “makes war quite untake-able,” any abstraction of our inner machinery is more “takable” that the thing itself (qtd. in Tom Wolfe).

I find it remarkable that the surgeon held McLuhan’s living brain in his hands—for he had to “lift [it] to get at the tumor”—a five hour operation. How swiftly such an image draws our attention inside the man’s body, past sulci and gyri of a the human folds of brain tissue, to McLuhan’s story writ somewhere therein, as if we could eventually learn to read the motivations of the man’s discomfiting probes: was McLuhan somewhere on the autism/Asperger’s continuum; was his affinity for star status hidden somewhere there; was the posthumously discovered “feline blood circulation” in McLuhan’s “external carotid artery” a kind of miracle (a “one-in-a-billion vascularization”) that saved his life (Coupland 199)? Knowing McLuhan’s desires to be “spared the details” and get through the operation allows me to assert that, if he were beside me in the brain display at the exhibit, he’d be commenting on the relationships among the elements inside the plexi-glass cases, their deli-case presentation, and the viewers’ very comments on them.

First woman: “That’s what they cut from me; that’s what they took.”

Second woman: “Tisk, tisk, tisk.”

Such relationships among the cadavers on plinths at Body Worlds, McLuhan would say, appeal to the “non-literate man who has no perspective experience”; one seeks not a relief from the technological world at all but an ultimate experience of the “oral-aural world” (Marchand 201). So as we reel slightly from having been thought of as “non-literate,” we’d be a moving target for McLuhan’s next remark: that we aren’t watching these non-alive/non-dead figures, but, “as it were, put[ting them] on,” just as a car or a pair of shoes is “worn”; such a space “transforms” us, he’d say, and we are as much comforted and put to sleep by this quieter “noise” that characterizes the “deep participation” of a spatial “immersion” into a new medium (Cavell 48). Recall that, here, each of us is a single point in a painting by Seurat; thus, we render the space of the gallery “automorphic space” rather than “pictoral space” so that, experiencing the gallery together, viewers comprise not an “enclosed” space but a space in which “which each person, each thing, makes it[s] own world”(McLuhan qtd. in Cavell 70).

Asked in 1960 what kind of period he would like to live in, McLuhan said he was “resolutely opposed to all innovation, all change, but [...] determined to understand what’s happening” because “the best way of opposing it is to understand it” (McLuhan qtd. in Tom Wolfe).

...know when to turn off the button

—McLuhan qtd. in Tom Wolfe

Starting with Yeat’s “sweepings of a street” then, I carry two images that inform me as to how McLuhan might react to the cadaver’s new lust for an audience that represents the vernacular. The first, told to me by Richard Cavell (my UBC McLuhan teacher and author of McLuhan in Space, a Cultural Geography), is a story of McLuhan mounting a Toronto bus heading to the University of Toronto and being struck by an ad inside the bus of a woman who holds a coke bottle to her lips, a man’s focus directly on those lips. To the astonished bus-riders, McLuhan nails it in one statement, “Coke-sucker.” He then proceeds down the length of the bus similarly summarizing the overall effect of the ads, bang on, every time.

The second is a film clip of McLuhan greeting his daughter, Mary who is dressed to be married, in which McLuhan does not remark upon her beauty or his own pride, as convention requires, but upon fatherhood as “an unusual idea,” an “abrupt aphoristic matter” that is quite “brief [...] as compared to motherhood which extends out for great periods”—until Mary swirls in her dress and drifts away from McLuhan’s critical abstractions and far off gaze; McLuhan seems unaffected by the momentarily still, familial human form of his daughter in front of him (qtd. in Tom Wolfe). Even watching this little clip of film years later is embarrassing.

Which is why I see Marshall McLuhan working the spaces among these enplinthed dead, shocking us with embarrassingly public statements where we’d expect funereal whispers. Deeply inappropriate, his comments are also a naughty thrill.

The plastinated cadaver celebrates

the anatomy of the unexamined.

McLuhan told us, “Turn off as many buttons as you can; frustrate them as often as you can” (qtd. in Tom Wolfe). But these cadavers are clever: the buttons are hard to find. We might hope to experience some profound understanding of scientific complexities of the body here, but the very room, he’d declare, is constructed not as visual space, not in touch with “logic,” but as “audile-tactile” and thus

side stepping our critical judgment

of it, as if the room teaches us not to question but simply to move (qtd. in Marchand 124).

And maybe he’d be right.

In the Tom Wolfe spirit of asking “What If He’s Right?” we should perceive this room of plastic posthumans as itself the threshold to “the space of the electric world”; perhaps what we recognize at Body Worlds is a synaesthetically similar experience to engaging in Facebook (see Figure 7) or internet surfing, since people there too “are hit with almost random bursts of information from all sides” (Marchand 124).

Having thus extended ourselves, having learned and internalized the electric world of the computer, and having allowed our very brain synapses to be rewired, we carry the physical experience of an electric “all-at-onceness” into the Body Worlds gallery with us (McLuhan & Zingrone 5). It’s part of our personal baggage now, such that we (each differently) engage in the tactile event of connecting science and religion. Progress meets up with our notions of death, of life-long learning, health and the afterlife. Billboards and playful displays all make splayed human tissue a possible draw. Like bargain hunting for what’s new and neat at the mall or curiosity shop, we flock to the cadaver as a pop art icon and have our personal favorites, mine being The Body Thinker who displays the nerves extending from the spine while he sports an attitude of calm self-respect.

Today, in the much greater junkyard of entertainment

and advertising presented on radio and television, the child

has access to every corner of the cultures of the world, past

and present. Roaming this vast jungle as a “hunter” the child

feels like a primitive native of a totally new

kind of environment

—McLuhan, From Cliché 182

has access to every corner of the cultures of the world, past

and present. Roaming this vast jungle as a “hunter” the child

feels like a primitive native of a totally new

kind of environment

—McLuhan, From Cliché 182

feels like a primitive native of a totally new

kind of environment

—McLuhan, From Cliché 182

—McLuhan, From Cliché 182

The masterful idea of presenting the human body as a travelling road show (conducting business to challenge Cirque du Soleil) begins “where all the ladders start/ In the foul rag-and-bone shop of the heart” (Yeats qtd. in McLuhan Cliché 20). It begins with a reaching into the heart to pull out an antique treasure; the cliché cadaver probe becomes art object and emblem of progressive science toward learning, entertainment and business innovation. McLuhan’s tetrad—the notion that new technologies always enhance something, render something obsolete, retrieve something previously obsolete, and reverse something—lets us arrive at a series of unsettled conclusions about the effect of the cadaver’s playful presence in society, conclusions that keep the question open.

As if we have suddenly gained x-ray vision, these mid-action cadavers are quite unaware we can see beneath their skin, but certainly our vision seems enhanced. As well, the condition of rigour mortis is certainly enhanced in these permanently stiffened bodies. But where is the value in that? Put another way, tissue decay is reversed: these bodies won’t so quickly transform into molecules and soil now—gone is the poetic cycling of the dead back into earth and life. Absent is the possibility of organ donation. The textbook is less exciting than the cadaver; although it risks boring the reader who is unused to sitting still, an anatomy text can reveal molecular processes of the nephron’s juxta-glomerular apparatus and the neuron’s sodium pump. These cadavers reveal only what’s visible to the human eye. Compared to Leonardo’s Anatomical Manuscript A, their muscles are not properly taut or relaxed, not convincingly illustrating the difficulty of being in the pose. What is really happening in the ways the structures of nerve endings differentiate for hot and cool stimuli or for pressure and pain is rendered obsolete; for these viewers, none of that matters. And yet, one aspect of the anatomy textbook is retrieved by Body Worlds in that cross-sections and open bellies are 3D versions of textual diagrams, just without their pastel colours; the textbook diagram has become tactile artifact because it is presented to us in an enveloping space of white noise of soft whispers. And because they are not primarily visual texts, we leave the criticism of visual culture at the threshold. The experience is as if we are finally grappling with Borges’ fabulously impossible metaphor of “a great circular book, whose spine is continuous and which follows the complete circle of the walls” (Borges).” We put on this “circular book,” complete with its entirely new emotional context, draping ourselves in equal parts ignorance and knowledge of these dead (Borges).

The biggest loss perhaps is the very rarity of the cadaver. When one leaves one’s body to science—to the unknown medical student—one’s gift carries a deep and self-less generosity; the gesture reflects a belief in education, an intimate exchange of ideas and a challenge to knowledge. In the word “education,” the root word ducere (to lead out) reveals the two-way exchange between student and cadaver that is already rich without an audience and is deserving of quieter reflection and perhaps a touch of laboratory humor. But just imagine one’s own cadaverous self as spectacle, or spectacle as part of the gift of giving, as it were, and the meaning of the gesture reverses from intimate and mutually respectful gift to public and exhibitory display.

One year in every ten

I manage it——

A sort of walking miracle, my skin

Bright as a Nazi lampshade

—Silvia Plath “Lady Lazarus”

A sort of walking miracle, my skin

Bright as a Nazi lampshade

—Silvia Plath “Lady Lazarus”

—Silvia Plath “Lady Lazarus”

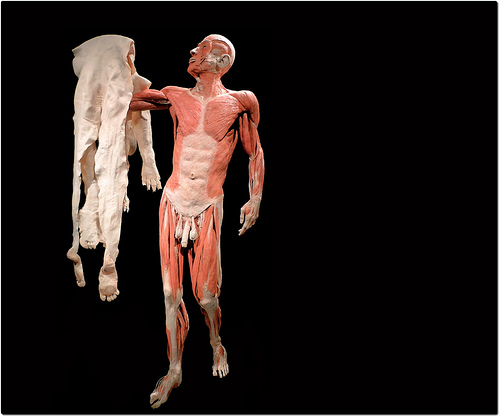

Most significant, I think, is what else is rendered obsolete: the body critical, the body in the context of history, politics, economics, and gender. The body is never neutral, is always contextual, except (at first glance) here; voice and agency are always somewhere. Would Silvia Plath’s images of a “Nazi lampshade” trigger, instead of the holocaust, a male form at Body Worlds with an entire envelope of skin drapped over one arm (see Figure 8)?

Figure 8.The entire organ of skin drapped over the arm.

“Jumping out of your skin in the new year” 14 Dec 2011.

Swamibu

In his personable biography, Douglas Coupland states that what makes McLuhan so “fresh and relevant” is his “focus on the individual in society, rather than on the mass of society as an entity unto itself” (142-3). McLuhan’s effect on social media choices has been huge in part because of his focus on the human sensorium and thus our individual response. Coupland suggests we regard McLuhan’s works as “an intricate and fantastically ornate artwork” that “creates its own language and then writes poetry with it” (142). So however he might confuse us in response to the cadaver’s balancing act in today’s culture, we can feel free to rearrange his points into new “poems” toward new meanings for the cadavers at Body Worlds: the poem’s speaker is implied in the technologies of plastination, and the arrangement of the words is guided by each viewer’s understanding of science, religion, notions of the dead in culture, and memories of his or her own dead. We participate in analysis, even as we question our participation and the business of paying to see cadavers.

cause dying is

perfectly natural; perfectly

putting

it mildly lively (but

Death

Is strictly

Scientific

& artificial &

evil & legal

—e.e.cummings “dying is fine)but Death”

putting

it mildly lively (but

Death

Is strictly

Scientific

& artificial &

evil & legal

—e.e.cummings “dying is fine)but Death”

Death

Is strictly

Scientific

& artificial &

evil & legal

—e.e.cummings “dying is fine)but Death”

Scientific

& artificial &

evil & legal

—e.e.cummings “dying is fine)but Death”

evil & legal

—e.e.cummings “dying is fine)but Death”

McLuhan sees “electric culture” as creating the “multiprobe [that] results in vast amounts of garbage” and returns the university scholar to a “primal state” (From Cliché 184). In his “Introduction” to From Cliché to Archetype—placed a little past the middle mark of the book because sections appear alphabetically—we are reminded that critical observation and fruitful analysis of Body Worlds must begin with a certain obvious and invisible “mound of refuse”: cliché and archetype (Yeats qtd. in McLuhan From Cliché 20). For McLuhan the printing press is the cliché’s source: Gutenberg is the “technology of imposing and impressing by means of fragmented and repeatable units,” none of which carry meaning of their own and so depend on a system of grammar and agreements about the meaning of a word (McLuhan From Cliché 119).

In his example of Ulysses, in which Joyce takes an old tale into the streets of Dublin to “explore contemporary consciousness,” archetype is “reversed” into cliché by moving the old tale into a new place, thus suggesting infinite repeatability (118). Sliding among the cadavers at Body Worlds I or II or IV, we appreciate the almost infinite possibilities for display, dollar signs in our eyes; imagine this going by the hosts of Dragon’s Nest. (Woody Allen’s next futuristic movie will include a background image of Body Worlds MCXI). As long as humans manage to wear their bodies out in unique ways—fashioning new and improved statements of strain combined with genetic bad luck—the repeatable unit of the letter becomes mere echo in planning the cadaver’s future.

...there is a paradox in cliché itself.

At the moment of truth it is tossed onto the scrap heap of the obvious an useless.

In retrospect, all new discoveries are obvious.

—McLuhan “Paradox” From Cliché 164

In retrospect, all new discoveries are obvious.

—McLuhan “Paradox” From Cliché 164

McLuhan claims, according to Philip Marchand, that the “one person who could see the invisible environment [...] was the artist;” to McLuhan, works of art function as an “advance warning system[s] of the effects of the new media on society” (168). Marchand goes on to say McLuhan argued new media held “almost animistic qualities” through which technologies “mated each other, produced offspring, and attacked and cannibalized each other” (169). Only the artist might just stop the maelstrom for a moment and let us see what we are subscribing to. Yet, Body Worlds presents the cadaver as pop art remix so as to grab the attention of the grade school teacher (with a science unit to cover) and to claim a precious spot in society—that of the artist: subversive, critically observant, and clutching a message in a bottle. The cadavers now are upright and happy, not dead on platters; they are “fragmented and repeatable units,” lending to McLuhan’s definition of technologies as effecting a “tribal” response, an always present moment, extending outward an “intimate psychological experience” (McLuhan From Cliché 119). McLuhan states,

For archaic or tribal man there was no past, no history. Always present. Today we experience a return to that outlook when technological breakthroughs have become so massive as to create one environment upon another, from telegraph to radio to TV to satellite. These forms give us instant access to all pasts. As for tribal man, there is for us no history. All is present, including the tribal man studied by Eliade. (McLuhan From Cliché 119)

Primitive or archaic life, according to Eliade in Cosmos and History, is characterized by an always present and “ceaseless repetition of gestures initiated by others” (McLuhan From Cliché 119). Certainly, Body Worlds invites one into a space where we can experience something largely untouched by human history and event—the human form. No wonder it’s so quiet.

We might agree the artist is “the one person who [can] see the invisible environment,” but we might not agree that the artist at Body Worlds is von Hagens. Perhaps the artist is ourselves, making something out of available materials of memory, knowledge, myth and even ignorance (Marchand 168). It’s a shifting question that calls for a glimpse at the use and abuse of another natural substance—the tree—equally open to manipulation toward new purpose driven meanings.

In a 2009 Enculturation collection, Derek Foster gives us ringside seats at an urban match of two masterful players, Kleenex and Greenpeace, where each pits against the other an opposing image that, like Rock ‘Em Sock ‘Em Robots, must unfold its given machinery and fight it out in the street. In “Kleer-cut(ting) Downtown: The Visual Rhetoric of Greenpeace’s Quest to Save the Boreal Forest,” Foster’s depiction of the fight of images is worth the visit: Greenpeace reconstructs a Kimberly-Clark paper product, complete with an adorable “dog-themed bus” (hear the inevitable awwh as it passes) in a great show of erecting a “giant Kleenex box in downtown city streets,” as if this giant object stands as not-tree and not-art, but which is all about the chopping down of the Boreal Forest (awwh becomes oh). Even hearing about this event, one comes to recognize the “Kleercut/Kleenex van” has dealt the superior punch.

For Foster, visual cues like these—and like cadavers at Body Worlds—are “a way of seeing” but “also a way of not seeing”; “a focus on object A involves a neglect of object B” (Burke qtd. in Foster). By Kleercut and by Kleenex, we are manipulated by the various appeals to our senses—the softness of a tissue, the sound of a forest disappearing into little boxes, a planet without oxygen—as we wrap ourselves in the meanings of natural and renewable resources rooted in life. At Body Worlds, we see not necessarily art and not necessarily science, and we must decide, from many possibilities, what these attractive dead mean to us. We are there to see but are even more distracted from our view of the cadavers. McLuhan, our leader in resistance to the specifics of dead human flesh, questions our very felt response. Reaction to art that occurs with one’s whole human sensorium is usually a good thing, allowing us to fully critique the work; but our vast and personal response eclipses what else is going on: all this is the manufacturer’s tool, and we are being toyed with. We forget to question the very provenance of the exhibit in both natural origins and technical ones. But, either because of a stroke in 1979 which left McLuhan unable to respond to others more than to declare, with varying degrees of excitement or frustration, “oh boy oh boy oh boy” or because he’d rather we engaged in our own critical analysis of the exhibition, McLuhan isn’t going to interpret this playfully advanced technology of the cadaver (Coupland 220). He’d rather leave us with the probe and make us think.

The “economy of the gift,” Margaret Atwood told me, is the exchange of what we are given in life and what we can make out of what we are given (Atwood). In consenting to have their bodies displayed, these cadavers maintain a “power to give” even after death (qtd. in Cary Wolfe 81). And “the ‘gift’ of death,” Derrida reminds us, is always given by the other (for “we never have an idea of what death is for us—indeed death is precisely that which can never be for us”) (qtd. in Cary Wolfe 84, 83). If these cadavers are not here for themselves, perhaps this is exhibit is not primarily for us either. Silent again, we search the room this time for evidence of McLuhan. These cadavers are like words and letters begging for arrangement into some new kind of poem: read it as enhancement, reversal, obsolescence or retrieval, or as concrete poetry or expressionist sound, or as sinister, cosmic, sacred—but read it. Decide what is it is to be engaged in living and non-living as spectacle and examiner, each viewer a moving point in an acoustic and tactile space. Decide whether McLuhan, surgeon of cultural circumstance, would say

we have wholly internalized Body Worlds

such that we are “free” to slip like “snake[s]” from our “own sweet agonized skin[s]” into the realm of the playful new cadaver (MacEwen 471). But the price is that we are then the “private pigment” of art show and advertising campaign; we are living illustrations of anatomy textbooks, echoes of former technologies (McLuhan qtd. in Tom Wolfe).

List of Figures

1 Billboard for Body Worlds: Exploration of the Mind at Stadium Skytrain Station. 14 May 2011. Vancouver, Canada. Photo: Slemon

2 Maureen Flynn-Burhoe. "Body Worlds 3: The Thinker | Art E. Rial." 2006. 14 Dec 2011. Used with permission.

3 Hailey Whitt. “The Nervous System, drawn at Body Worlds.” 2010. Slemon’s Science 201. Emily Carr University. Used with permission.

4 Carolina Perez. “The Femur, drawn at Body Worlds.” 2010. Slemon’s Science 201, Used with permission.

5 Billboard for Body Worlds: Exploration of the Mind at Granville Skytrain Station, Vancouver, Canada’s 14 May 2011. Photo: Slemon

6 Theunis Snyman. “Brain, bone and skin, drawn at Body Worlds.” 2010. Slemon’s Science 201. Emily Carr University. Used with permission.

7 “Well, it’s about being dead.” Facebook post. 1 June 2011. Screen photo: Slemon. Used with permission.

8 Swamibu. “Jumping out of your skin in the new year” 14 Dec 2011.

Works Cited

Atwood, Margaret. Personal communication, Vancouver International Writers & Readers Festival, October 1996.

Borges, Jorges Luis. The Library of Babel. 15 June 2011. Web.

Cavell, Richard. McLuhan In Space: A Cultural Geography. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002. Print.

Conrad, Daniel. Dir. Accident By Design: NFB: Dir. Daniel Conrad, NFB, 1998. Film.

Coupland, Douglas. Marshall McLuhan. Toronto: Penguin Canada, 2009. Print.

cummings, e.e. “dying is fine)but Death.” 20th Century Poetry and Poetics. Ed. 5. Ed. Gary Geddes. Don Mills: Oxford, 2006. 139. Print.

Foster, Derek. “Kleer-cut(ting) Downtown: The Visual Rhetoric of Greenpeace’s Quest to Save the Boreal Forest.” Enculturation. 6.2 (2009). 12 May 2011. Web.

Gossage, Howard Luck. “You Can See Why the Mighty Would Be Curious.” McLuhan: Hot and Cool.New York: New American Library, 1967. 20-30. Print.

MacEwen, Gwendolyn. “Manzini: Escape Artist.” 20th Century Poetry & Poetics. Ed. 5. Ed. Gary Geddes. Don Mills: Oxford UP, 2006. 471. Print.

McLuhan, Eric and Frank Zingrone. Essential McLuhan. Concord, Ont: BasicBooks, 1995. Print.

McLuhan, Marshall. Counter-blast. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1969. Print.

McLuhan, Marshall with Wilfred Watson. From Cliché to Archetype. New York: Viking Press, 1971. Print.

McLuhan, Marshall. “Inside the Five Senses.” Empire of the Senses. Ed. David Howes. New York: Berg Publishers, 2005. 43-54. Print.

McLuhan, Marshall. “Where the Hand of Man Never Set Foot.” McLuhan: Hot and Cool. New York: New American Library, 1967. 114-23. Print.

Marchand, Philip. Marshall McLuhan: the Medium and His Messenger. Toronto: Random House, 1989. Print.

Park, Katherine. Secrets of Women: Gender, Generation, and the Origins of Human Dissection. New York: Zone, 2006. Print.

Shakespeare, William. King Lear. Scarborough: Signet, 1963. Print.

Steigler, Bernard. Technics and time, I: the Fault of Epimetheus. Trans. Richard Beardsworth & George Collins. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1998. Print.

Slemon, Jane. “500 years: the cadaver—a self-portrait: Leonardo da Vinci’s Anatomical Manuscript A.” Vancouver Art Gallery, 20 April 2010. Lecture.

von Hagens, Gunther. No Skeletons in the Closet — Facts, Background and Conclusions. Institute for Plastination, November 17, 2003. Pdf.

Wolfe, Cary. What is Posthumanism? Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010. Print.

Wolfe, Thomas, Dir. Marshall McLuhan: The Man and his Message. Toronto: Broadcasting Corporation, 1984. Film.