Arthur Asa Berger, San Francisco State University

Enculturation: http://www.enculturation.net/writing-myself-into-existence

(Published January 20, 2012 )

Illustrated with Drawings and Photographs by the Author

Advertising: or the Agent in the Agency

I had an excellent Catholic education in high school, which is remarkable since I attended a public school and I’m Jewish. Most of my teachers were Catholics who were educated at Boston College or Holy Cross. One of my teachers, known as “Preacher Kearns,” had everyone in the class pray before we took our math exams in his class. When I was in high school, at Roxbury Memorial High School for Boys (in Boston), I didn’t have the slightest idea about what I wanted to do with myself. I knew that I liked to write and I liked to draw. What to do? I took many different tests—one of which was called the Kuder Preference Test, if I remember correctly—and they all came out with the same answer: go into advertising. Maybe it was because the tests recognized the creative aspects of my personality and thought that channeling this creativity into advertising made more sense than, say, becoming an accountant. Or maybe they discerned that I had a lot of potential as a flimflam artist?

I’ve always had negative feelings about advertising. I admire the creativity of many of the people in the business, but I am very uneasy (to put it mildly) about the power advertising has to shape individual behavior and the way it has created a consumer culture in which, as the saying goes, “in life, it is the boys with the most toys who win.” In one of my books, Pop Culture, I wrote about what I called “The Affordinary Man” (and Woman), who measure life in terms of the goodies they can afford and measure other people the same way. For this so-called “Affordinary Man” (and Woman) the numbers on the stock market pages are of all-consuming interest (meant literally and figuratively) and determine how he feels about himself and his place in the universe.

And it is advertising, of course, that helps shape the consciousness of these “Affordinaries,” as marketers would put it. Marketers in the United States are always dividing the American public into different groups, based on things like age, sex, race, religion, zip code, socio-economic status, and consumption patterns. These groupings are supposed to help advertising agencies learn how to design their ads and commercials to appeal to specific groups that a company is targeting. We are constantly told that we are important as individuals (“We do it all for you”), but for companies, what’s most important is whether we’re 18-45 years old and have a certain amount of discretionary income to spend—or that we’re willing to borrow money to buy things we often don’t need. And the advertising agencies are the ones who create the print ads and radio and television commercials that move so many of us in such profound ways.

Figure 1: The Agent in the Agency

Some television commercials are absolutely brilliant works of art, or of persuasive art, to be more precise. The question one must always ask about advertising is whether it is ethical to manipulate people, to get them to do certain things that you want them to do. Advertisers argue, of course, that they are relatively powerless and that what they do is provide information that people can evaluate and then make up their own minds. It’s an interesting exercise to turn off the sound and examine the images in a commercial—you’ll see incredible use of body language, of facial expressions, of everything the actors and actresses can do to generate an emotional response in those who view these works. Advertising is not, for the most part, information; it is emotion!

In 1998 I was fortunate enough to win an award by the Advertising Education Foundation and spent three weeks at Goldberg Moser O’Neill, a large advertising agency in San Francisco, as “visiting professor.” Everyone was very nice to me and I learned a lot, wandering around, chatting with various people. They were, as a rule, very bright and hard working, and kind to give me so much of their time. There was, I could see, a mountain of labor behind every print ad or commercial.

One day I was chatting with Fred Goldberg, the number one honcho of the agency (now retired), and we were talking about an ad he was looking at in a newspaper. “It’s a lousy ad,” Fred said, “but the amazing thing is that even lousy ads work!” If even the lousy ads work, what hope do most people have of not being affected by them, especially since we are exposed to so many print ads and radio commercials and television commercials in the course of a given day. “It’s a 260 billion dollar a year business,” he said, “and most of the companies keep advertising because they hope that one day, somehow, they will get an agency to create a blockbuster ad for them that will turn everyone on. It’s like playing the lottery. One company gave me hell about the amount of money we were spending on corned beef sandwiches on the shoot for a commercial we were making for them, but didn’t think twice about signing the media bill for almost ten million dollars worth of air time.”

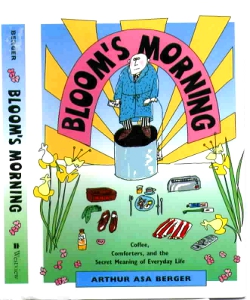

Figure 2: "Umberto Eco"

Some teenagers were asked by a researcher whether they were affected by advertising. “No,” most of them said. “We’re aware of advertising but we’re not affected by it.” Being deluded about one’s behavior is not unique to teenagers, but the idea that teenagers aren’t affected by advertising is similar, as far as truth values are concerned, to saying the earth is flat! Teenagers have hundred of billions of dollars of discretionary income, and the advertising agencies make sure, as best they can, that teenagers and their money are soon parted.

In 1963 I went off to Milan for a year, where I met Umberto Eco and spent some time with him and his circle of friends. Then I came back and wrote my dissertation on Li’l Abner in the American Studies Program at the University of Minnesota, and got a job at San Francisco State University. I had three offers: one at the University of Southern Florida, in humanities; one at Southern Illinois, in literature; and one at San Francisco State College (now University), in a small social science department. I chose San Francisco, for obvious reasons. It was the lesser of the institutions, but it was the one with the best location. I ended up after a dozen years in the social science program in the Broadcast and Electronic Communication Arts Department where I taught courses on media criticism (from a cultural studies perspective) and writing.

Assassin of Academics

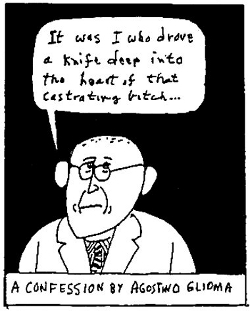

Figure 3: "A Confession by Agostino Glioma"

I am, I must confess, an assassin of academics. I’ve written a number of dark comic academic mysteries in which I’ve managed to kill, using various means—knives, poison, guns, poison arrows, bombs—a dozen or so professors and an occasional dean and college president. It is very therapeutic killing off professors and others involved in academia. In my mystery novels I also express a certain kind of ambivalence (or is it sadness or anger) I feel about what is happening in universities nowadays as they become more and more corporatized.

Thus, in my comic mystery Die Laughing, I have my narrator, Agostino Glioma, a berserk professor from the University of California at Berkeley, speculate about academic life. He had murdered six professors in a previous book, The Hamlet Case, and has just been released from San Quentin Prison after doing his time.

In universities, one gets ahead by projecting an attitude of high seriousness and giving people the impression—often false, of course—that one is working on important matters. You have to develop a certain look—the look of a strategic thinker who is scanning the distant horizon for the newest ideas. You of course are thinking about screwing a beautiful co-ed in the fourth row of one of your classes but you seem to be struggling with enormous thoughts and weighty problems.

It helps if you can write in an unintelligible manner; the French are masters of this. I don't think anyone really understands what Baudrillard or Derrida or Foucault or Deleuze writes. The more opaque and elliptical the better, and the more nonsense you write—with a sense of assurance and confidence to carry it all off—the higher your reputation will be. That is because academics, all of whom think they are brilliant and remarkable, will assume that since they can't figure out what you are talking about, you must be even more brilliant than they are. I always advise young faculty members to read the French philosophers and culture critics and imitate them stylistically.

If you publish very little, you explain that your work is theoretically important and that you are not a hack, like certain colleagues you could mention in your university, whose work is everywhere. You mention the term "public intellectual" with a sneer. It is quality, not quantity, that counts, you say. Your work, you suggest, has taken enormous thought and energy, and if it is not well received critically, it is because you are so far ahead of your time. Attitude is all in academia and you must convince those who dole out the money, the deans and the provosts, that you are one of their brightest stars.

The ultimate dream of university administrators, it seems, is to have a university with only administrators and students and maybe a handful of professors, at the most. The only problem is that a virtual professoriat teaching courses on the Internet would lead, ineluctably, to a virtual set of university administrators. University administrators want to avoid virtuality at all costs. In recent years they have been multiplying at an enormous rate. Professors, of course, would like to rid universities of administrators, who came to administer and take care of minor bureaucratic functions—parking and that sort of thing—and stayed to command.

I’ve been in universities for most of my adult life. (I don’t know whether I should be pitied or be given a medal for foolhardy valor.)

Figure 4: Postmortem for a Postmodernist

I now obtain a good deal of pleasure by writing comic academic murder mysteries that also generally deal with some topic, such as postmodernism or ways of interpreting Hamlet or mass communication theory. If you’re going to be a disgruntled professor, you should find a way to make it pay off, I say. For example, I wrote a mystery, Postmortem for a Postmodernist (AltaMira Press), which explains different perspectives on postmodernism. In this mystery, a professor from the University of California at Berkeley, Ettore Gnocchi, is killed four different ways on the first page.

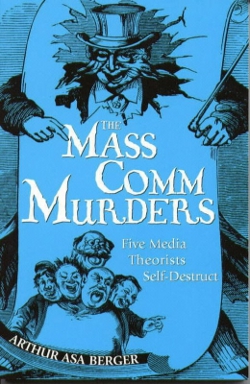

In another one of my mysteries, The Mass Comm Murders: Five Media Theorists Self Destruct, I deal with mass communication theory. In this mystery, five media theorists kill one another off. In my mystery The Hamlet Case (Xlibris), I have my hero (or is it villain) Agostino Glioma kill off six professors, but not before each of them has offered a different interpretation of Hamlet. They were all members of the editorial board of the journal he edited, Shakespeare Studies, and he was afraid they were going to replace him as editor.

The most important thing about my academic career, as far as I am concerned, is that it gave me the time and freedom to pursue my scholarly interests and write my books. Many professors mistakenly argue that the three best things about academic life are, sad to say—June, July and August! They are, of course, forgetting about the month between semesters!

Aristotle’s Lost Book on Comedy

One of my books I published with Xlibris, an Internet print-on-demand publisher, is a pseudo-translation of Aristotle’s “lost book” on comedy. It is the first literary hoax I’ve written. (Some would claim all my books are hoaxes.) I am, I must confess, something of a trickster and put-on artist, and I’ve had a lot of fun, over the last forty years, in that role. So I imagine it isn’t too surprising that I perpetrate a literary hoax.

My idea was to pretend to discover and then to translate and annotate Aristotle’s famous “lost” book on comedy. He mentions this book in his writings but nobody has ever seen it and there is a question about whether Aristotle never got around to writing it or whether he wrote it but it has been lost. I took the latter tack and parodying his style, to the extent that I was able, I wrote a book (actually a long article) in which I claimed to have discovered Aristotle’s lost book on humor and translated it from the Greek, with numerous annotations.

What I did, actually, was take a glossary on the forty-five techniques of humor that I had elicited in some research I did many years ago (and written about in my books An Anatomy of Humor and The Art of Comedy Writing) and using Aristotle’s “voice,” have him explain most of these techniques. To flesh out the book (and some of Aristotle’s books are relatively short, you should understand), I annotated my fake Aristotle and offered various jokes and other material relevant to the study of humor.

Figure 5: Aristotle: Comedy

When I did this I still had only about forty pages of manuscript—I needed to figure out a way to get a book-length manuscript. So I added a comic mystery, “The Aristotle Case,” in which the board members of “The International Aristotle Society” (which I invented, though there probably are groups like it) had a panel at a meeting of the Modern Language Association to discuss the authenticity of the translation. I also put myself on the panel. One of the members is murdered and an investigation ensues. In the investigation, interestingly enough, I am interviewed by my detective.

I had my typical international cast of characters: male and female professors from England, from Russia, from Germany, from Italy, and France...each of whom is involved with one another in complicated ways—love affairs, broken love affairs, as well as different perspectives on Aristotle. I use them to spoof stereotypes people have about people from different countries. And I used my detective, one Solomon Hunter, who has been in most of my mysteries, to solve the murder. The French semiotician friend of mine, Daniel Dayan, is convinced that I modeled one of my characters in the book, Yves-Marie Fess, on him.

Because it is a rather eccentric book, and I didn’t think any regular publisher would be interested in it, I decided to publish with it Xlibris.com. Until February 28, 2001 you could actually publish books with Xlibris at no cost. That is, Xlibris would design a cover and set the book into type, using the file you sent them on a diskette. Then, Xlibris would print copies of the book, one at a time, as orders came in. After February 28, 2001, the cost for books went to $200, so I made certain I got the manuscript in before that date.

Figure 6: "It's a rare medium"

These books that Xlibris and IUniverse published are listed at Amazon.com and BarnesandNoble.com and are printed on demand, thanks to new developments in printing technology. I don’t believe it will be an electronic book, that people can download and read on computers (I might be wrong about this), but it will be a book that looks like any other book. The staff at Xlibris actually did a decent job with the cover, too.

I don’t know how many people, other than myself, will order copies of the book, but like all authors, I feel that if a book is available, someone may order it, and that’s what’s important. There’s always a chance that a book will catch on.

I must report a bit of fun I had with my Aristotle book. I saw on the Internet that an electronic journal was looking for articles that mixed genres, so I sent them a dozen pages of the Aristotle “comedy.” My thought was that I had a bit of fiction (the so-called translation of the “lost book” on comedy) and a bit of fact—my annotations. I received an e-mail back saying that while the judges thought that while my translation of Aristotle was fine, nobody could see how I was blending or mixing genres. They didn’t realize that my translations was a hoax, and pretended that they were able to evaluate my “translation” of Aristotle from the Greek. I got a big kick out of that.

Barthes

Figure 7: "Roland Barthes"

When I read Roland Barthes’ Mythologies, I felt a wonderful sense of vindication and relief. For here was Roland Barthes, one of France’s most influential intellectuals, writing a book about life in France, and what did he write about? Wrestling! Garbo’s Face! Steak and Chips! Toys! Striptease!

Is that the kind of thing one expects from a world-famous scholar? What’s going on here? Mythologies reminded me, in a way, of McLuhan’s marvelous and under-appreciated book The Mechanical Bride, which treated print advertisements and comics, among other things, as signs to be decoded.

Barthes explains in the preface to his 1970 edition of Mythologies that he is offering “an ideological critique bearing on the language of so-called mass-culture,” which was occasioned by his reading Saussure’s book on semiology. “I had just read Saussure and as a result acquired the conviction that by treating ‘collective representations’ as sign-systems, one might hope to go further than the pious show of unmasking them and account in detail for the mystification which transforms petite-bourgeois culture into a universal nature.”

Barthes wrote the essays in Mythologies one per month between 1954 and 1956 “on topics suggested by current events.” Each essay was an attempt to strip away the mystification from important aspects of French life, for each of his topics was accepted as that “which goes without saying,” and he was trying to show that this naturalness was cultural and as result of the way the media presented things to the French public.

I had been trying to do the same thing, long before I had read Barthes or McLuhan, because I sensed, like them, that it is in our commonplaces that one can tease out the elements of our fundamental beliefs. We may not be conscious of these beliefs or be able to articulate them, if asked. But people in most cultures learn certain core principles that guide their thoughts and behavior, and it was these hidden or covert aspects of culture that I’ve always been after.

Barthes wrote a similar book in his Empire of Signs, except that his book dealt with Japanese culture. He isolated a number of topics that he thought were important—Japanese chopsticks, stationery stores, tempura...it is from topics like these that Barthes presented his picture of Japan. He pointed out that he was not offering a portrait, a coherent and unified study of Japanese culture, but, instead, a discussion of certain aspects of Japanese culture that struck his attention and which he thought had resonance and significance.

When I read McLuhan and Barthes and Saussure, it was if a dark veil were lifted from my eyes. I instinctively felt that many so-called “trivial” matters, like wrestling (about which I’d written) and comic strips (I’ve written two books about comics and a number of articles about them) and McDonald’s hamburgers (I wrote an article on McDonald’s titled “The Evangelical Hamburger”) were really of considerable importance—if one could learn how to read them. Saussure provided the theory and McLuhan and Barthes the examples, and some theory, that set me on my course.

I wrote one book, Bloom’s Morning, that did the same kind of thing Barthes did in Mythologies except my book had a narrative line to it and was tied much more to everyday life’s domestic routines.

Bloom’s Morning

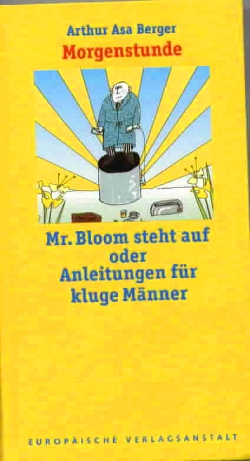

Figure 8: Bloom's Morning

The day my book Bloom’s Morning was published I started believing in miracles. I say that because it is a somewhat strange little book and though I came close to getting it published a few times, I had been afraid that nobody would ever publish it.

My original title for the book was Ulysses Sociologica. What I planned to do in the book was take one day in the life of a typical American, who I named Bloom, and examine, from an anthropological and sociological point of view, all the different objects he used and rituals he went through. That is, I would take James Joyce’s Ulysses as a model and write a sociological (in the broadest sense) study of everyday life in America.

I got the idea in the early seventies, and have numerous places in my journals where I speculate about how such a book might be written and what I might deal with. In 1982 or thereabouts I bought a computer—a Commodore 64 for $900. I thought my son Gabriel might become interested in computers but he never took to them—until recently, that is, and now he works as a senior engineer for a Silicon Valley company. I also had, for the first time, a very elemental word processing system.

I decided, then, that I would learn how to use the word processing program by writing Ulysses Sociologica, and so, over the next month and a half I wrote something like thirty-five essays, on topics I had decided were important signifiers of American culture and values. I had set a number of pages aside in my journal and listed the topics I might deal with...and brainstormed on each of them. It was very difficult work because for my book to work I had to discover something interesting and surprising about each of my topics—whether it was the clock-radio, which was my first topic, or toasters or gel toothpaste or slippers or trash compactors, which were other topics I wrote about.

Figure 9: Morgenstunde

I also did a drawing for each topic I wrote about. Over the course of time I revised the essays a bit, but not substantially. I later turned them into a little book, based on pasting the illustrations on the top of a page and pasting the text I had written for a given topic beneath it. I duplicated twenty-five copies and had a “book,” so to speak. Over the course of a number of years I found two or three editors who were interested in the book and liked it, but who could never convince their publishing committees (read marketing directors?) to allow them to publish the book. So I despaired of publishing it.

In the early nineties, I saw a notice that Douglas Kellner, a philosophy professor at the University of Texas, was editing a series on contemporary culture. I sent him a query about my book and he said he’d like to see it. I sent it to him and he informed me that he would like to publish the book. But he had to get an editor at the publishing house that was doing the series to accept it. That editor said he found the book interesting, but he thought I should write an introduction to the book and a conclusion, so I wrote an introduction on the theory of everyday life, and I wrote a conclusion about myth, culture and everyday life. The editor kept it for six or eight months and then rejected it. It’s not unusual, I should point out, for editors to keep a book manuscript for months—even years—and then reject it.

“God,” I thought, “I’ll never again come this close to getting Bloom’s Morning published.” And so I reluctantly concluded, once again, that the book would never be published.

Then, in 1995 or 1996, someone told me that there was a very creative editor—a poet, actually—at Westview Press in Colorado named Gordon Massman. I sent him a query and he said he’d like to see the book. I sent it to him and he called and told me he loved the book. He said that when other people at Westview mentioned it, they started rolling their eyes.

I had sent him a print out of the manuscript, so he didn’t see the drawings. I told him about them and he told me to send them to him right away. They made a huge difference. Once they saw my drawings, he told me, his colleagues at Westview decided they loved the book, and Gordon was able to convince the editorial committee to publish it.

I can remember how excited I was the afternoon he called. I still couldn’t believe that it would get published. Something will happen, I kept telling myself. I also did a drawing for the cover and some other drawings—of Freud and Joyce—for the introduction. I put Freud in because I adopted a technique of his from his book on dreams. In one place he recounts a dream and then takes every part of the dream and analyzes it. I did the same with my book, and so my first chapter was “Bloom’s Morning.” It reads as follows:

Mr. Leopold Bloom was awakened by the buzzer in his digital clock radio. He was lying on a king-sized bed in the master bedroom of his house. He lay beneath a designer sheet and a comforter, which he tossed aside, and slid out of bed. He was wearing a pair of pajamas. The broadloom carpet in the bedroom felt soft and comfortable. He put on his slippers and went to the closet where he took out his jogging outfit and got into it. He went for a jog around the neighborhood, returned, got undressed, put on a bathrobe, and ambled over to the bathroom. He took a long, hot, invigorating shower. He loved the smell of the new bath soap he had purchased recently. He shampooed his hair. Then he put on his bathrobe again and dried his hair with an electric hairdryer. Next he brushed his teeth using an electric toothbrush, took a shave, and put on his underwear. Then he put on his stockings, a suit, and his shoes, selecting a tie to wear, and went to the kitchen.

There wasn’t much in the refrigerator, so he slipped out of the house and strolled to the local supermarket, where he picked up a few items, and returned home. The morning newspaper had arrived. He made himself a big breakfast: orange juice, cereal, bacon and eggs, coffee, and toast. He put his garbage in the waste disposal, his dirty dishes in the dishwasher, and an empty cereal carton in the trash compactor and hear the pleasant sound of the morning mail being slipped through the front door.

That was Bloom’s morning.

In my book I analyze the various objects mentioned and rituals engaged in by Bloom.

I had written the book assuming it would be sold as a scholarly book that might be adopted in courses on American culture or the sociology of everyday life in universities. Instead, for some reason, it was marketed as a trade book. That meant that three months after Bloom’s Morning was published, it died. It was remaindered and that seemed to be the end of the story.

Not quite. It turns out that IUniverse.com has a program of reprinting books that are out of print, so now Bloom’s Morning is available, on a print-on-demand basis, from IUniverse.com. I don’t know whether it is correct to say that my Leopold Bloom still lives; perhaps it is more accurate to say that he exists in a kind of limbo, in a state of radical potentiality, waiting to be brought back to life by anyone who might find his story worth examining and who has fifteen dollars.

Publisher’s Weekly’s review of the book concluded as follows:

Using toasters and supermarkets as springboards, Berger mounts a devastating critique of the increasingly impersonal, dehumanized quality of our lives.

Some reviewers considered the book far-fetched and silly while others loved it. My thought is that if I’ve mounted a devastating critique of American consumer culture and alienation with Bloom, he did not live in vain. And Bloom lives on elsewhere, too—my book has been translated into German and, of all things, into Chinese.

Clerihews

In my younger days I wrote a lot of comic verse. I also developed a unique version of the clerihew that was based on the names of famous people. Here are some of my clerihews.

Aga

Khan,

but Immanuel

Kant.

Dame May

was Witty

But John Greanleaf

was Whittier.

Oscar

was Wilde

but Thornton

was Wilder.

Clare Booth

was Luce

but Martin

was Luther.

They are silly little efforts, but mildly amusing, I believe...perhaps because they are so economical.

Computers and My Career as a Writer

The computer really changed my life—and, no doubt, the lives of most other writers. For what word processing did was make it possible for me to write something and then, without having to retype it, save it and revise it as many times as I felt necessary. I was liberated from Wite-Out and the typewriter. In addition, e-mail makes it possible for me to communicate with editors all over the world and send them material that arrives in little more than an instant.

For example, I do book reviews for The Journal of Communication, a scholarly journal read by professors who teach communication in universities. The book review editor sends me e-mail messages asking me whether I’m interested in writing a review of this book or that one, and if I say “yes,” she sends the book to me. When I’ve written the review, I e-mail it to her. Just recently, a professor in Russia sent me a book by e-mail. She divided the book into several parts and sent each part to me as a separate file.

A number of years ago I thought it would be a good idea to write a dictionary in which I explained, in rather simple language, the terms used by literary theorists and culture critics. So I made a list of the most important terms and wrote my dictionary. I found that no publishers were interested, because dictionaries are seen as reference books and editors expect rather long manuscripts. So one day I sat down at the computer and pulled up the table of contents I had made for my dictionary. After studying it a while, I figured out that I could pull the various items together in chapters dealing with semiotics, psychoanalytic theory, sociological theory, Marxist theory, and literary theory. It only took a few hours to reassemble the book. Then I spent some time adding material here and there to provide continuity. It only took a couple of weeks. I now had a manuscript I titled Cultural Criticism, and I was able to find a publisher for it—Sage Publications, which has published something like ten of my books over the last twenty years.

So, the computer has really revolutionized my life. I know very little about computers and how they work. This always mystifies my son, Gabriel. He wants to explain to me, in detail, how they work, but I always say, “Look, Gabriel. If anything goes wrong, I’ve got you to fix things.” The number of writers and others who rely on their sons and daughters, and in some case grandchildren, to fix things when computers go awry, must be legion.

I never spend more than a couple of hours writing at a time. Because of my productivity, many of my colleagues think I’m at the computer ten or twelve hours a day, but that isn’t true. When I decide to write a book, I work on it steadily, but seldom more than two or three hours at a time. You can do a lot of writing in two hours, if you don’t waste time daydreaming and playing computer games.

Creativity, Comedy, and Writing

I was a visiting professor for a year at the Annenberg School for Public Communication, invited there by the dean, Peter Clarke. I suspect that he, like many other academics, didn’t consider me a serious scholar because he told me I was “data free.” I had written an article about deodorants with a whimsical title, "I Stink, Therefore I Am," suggesting that our passion to remove body odor was tied, ultimately, to Puritanism, perfectionism, and a fear of death.

In the same vein, I had speculated, in a piece called "To Buy is to be Perceived" (playing upon Bishop Berkeley's famous dictum "to be is to be perceived"), that most of us lead lives, not only of "quiet desperation" but also of relative anonymity and that, generally speaking, it is only when we purchase things that anyone pays much attention to us. And when they do, it is only pro forma. We get few personal letters nowadays, and need the bills in the mail to remind ourselves (prove to ourselves?) that we do, in fact, exist.

I developed a theory called ErosGOPanalia: The Berger Hypottythesis. Peter Clarke was interested, among other things, in political communication. It dawned on me that he might have read my essay about a concept I called "ErosGOPanalia," which argued that conservative Republicans like George W. Bush, members of the Grand Old Party (GOP), were anal erotics who had transferred their infantile hangups about retaining their stools to a fear of government spending (for anything except military weapons, that is).

It was, then, the toilet training of the young children who were to become powerful politicians, that shaped, in large measure, their political behavior as adults. The child is not only father to the psychological man, but also, and Aristotle would be pleased to hear this, to the political man. I had even written a short parody of a famous A.E. Houseman poem, to add to the argument:

The potty does more

Than Milton (Friedman) can

To justify the ways of the NAM

To man.

This concept of ErosGOPanalia was, I recognized, a radical notion. I had sent this article, subtitled "The Berger Hypottythesis," to a very distinguished economics journal and received a letter from the editor that read, in part, as follows:

Dear Professor Berger:

Thank you for sending your article, ErosGOPanalia: The Berger Hypottythesis, to us for consideration. The editorial staff has read your article with care and concluded, unfortunately, that it is not suitable for publication in this journal...or any that we can possibly conceive of.

Economists, of course, have no sense of humor, so I was not surprised by the rejection. I had sent my article assuming I would get a rejection something like the one I did, but the letter they sent exceeded my fondest expectations.

I must confess that a considerable number of sociologists, anthropologists, psychologists, culture critics and others haven't liked my theories, my articles, my books and my work, in general. Some of them don't like me, either. But, I keep wondering, is it because I am a man without quantities or is it for some other reason?

I had written a book, The TV-Guided American, which was published in the mid seventies. This book was reviewed by Jeff Greenfield, in The New York Times, with the concluding line,

Berger is to the study of television what Idi Amin is to tourism in Uganda.

Greenfield did not take kindly to my use of psychoanalytic theories and semiotics to analyze television. This is a typical layperson's response to works by scholars which is full of, to the common man and woman, "arcane" language and obscure theories. I should add that my writing is quite “accessible,” so even though I deal with psychoanalytic theory and semiotics, I do so in a way that can be easily understood. But I can appreciate how many people feel when they read material full of academic-speak.

Decoder Man

Figures 10, 11:

"Arthur Asa Berger: Writer, Artist, Secret Agent"

Figure 12: "Decoder-Man"

In the Spring 1974 issue of The Journal of Communication, I published an article titled “The Secret Agent,” and then took on, for the fun of it, the mock-identity of being a scholar and secret agent. I used a caricature I had made of myself as a secret agent in letters and I also made an embosser with my name and writer, artist, and secret agent on it. I often stamped my letters with this embosser.

But after a number of years, as I wrote more and more from the standpoint of a semiotician, I decided to add another super-hero characterization to my repertoire, and so I became “Decoder-Man.” I did a caricature of myself as a super-hero called “Decoder-Man,” whose mission it is (comic strip heroes always have missions) to decode anything and everything that strikes my attention as being interesting.

I wrote a small book, Signs in Contemporary Culture: An Introduction to Semiotics, in which I explained some of the basic principles of semiotics. In this book, each chapter has two parts: part one is an explanation of some aspect of semiotics, and part two is an application of this topic to some kind of signifier in American culture. My thesis was that we are all, whether we recognize it or not, semioticians. That is, we all try to make sense of matters like facial expressions, clothes people wear, people’s body language, status symbols, and so on.

The important thing is to see such phenomena as signs, and more specifically signifiers, and to try and figure out what the signifieds are. What semiotics does, among other things, is to attempt to understand how people decode things and to formulate rules for doing so and offer explanations of how this decoding should be done.

My book Bloom’s Morning, which I discussed earlier, analyzes American culture by decoding the various rituals and objects that are part of a typical male American’s morning. I did this because I see American culture (and all cultures) as full of signs. Charles Sanders Peirce, one of the founding fathers of semiotics, explained it this way. He writes that “...the universe is perfused with signs, if it is not composed exclusively of signs.” When you see things not in terms of being objects or in terms of their function but as signs, you are then seeing the world from a semiotic point of view. And if everything is a sign—granted that some signs are more important than others—there’s plenty of work for me, as Decoder-Man, and for other decoder men and women, to do.

Freudian Slips

I often use Freud’s concepts in my work, because I find them so useful. They help me explain the significance of events in narratives that often seem trivial or meaningless. Freud’s notion that seemingly unimportant slips of the tongue often reveal important things about a person is the metaphor I use in a good deal of my work. If you don’t believe in the unconscious, of course, then life becomes much simpler when you interpret a text. You take everything a person says or does as not having any deeper meaning or hidden significance, and that’s that.

I wouldn’t say that I’m a doctrinaire Freudian and accept everything he’s written as the gospel, but I don’t see how you can analyze media and popular culture without recognizing the importance of the unconscious and of the various defense mechanisms Freud discusses and other similar matters that fall under the rubric of psychoanalytic thought.

Figure 13: "Sigmund Freud"

In 1984 I wrote an article for The Los Angeles Times in which I suggested that video games were masturbatory activities (kids loved to play with their joy-sticks) and that Pac-Man was, from a developmental point of view, a regressive game. We had been playing phallic games like Space Invaders in which we shot down aliens with phallic cannons and ray guns, and then, with Pac-Man, we regressed to the oral stage—eating dots.

The newspaper received a number of letters from outraged readers who though my article was sheer lunacy and said so in very forceful ways. The nice thing about Freudian theory is that we can explain this reaction as a kind of repression on the part of the people who could not face up to the sexual nature of this video game.

I explained once that the Washington Monument was a gigantic phallic symbol—a suitable monument for the father of our country. This was greeted by many with disdain. Interestingly enough, a sign maker who did many of the signs in Las Vegas once revealed that the owners of the hotels told him they wanted “a big phallic symbol going up in the sky as far as you can make it.” I had analyzed household appliances in terms of whether they were masculine (penetrating) or feminine (incorporating) and psychoanalyzed Dick Tracy as an obsessive with a distorted superego.

Writing Myself into Existence

I am a study in self-creation. I almost feel that I’ve written myself into existence in my journals. I developed my mind, my style, and my sense of myself—with liberal borrowings from here and there. I may be a fictional character or imaginary being who believes himself real? Who knows?

That’s what I wrote on the first page of my 32nd journal, Relations, on March 7, 1976. Now, more than 25 years later, I see myself as a writer who happened to teach, in contrast to being a teacher who happened to write. I also believe that my writing helped me be a better teacher, since I often had new ideas and new material to share with my students.

Figures 14, 15: Excerpts from Berger's Journal

I’ve spent something like forty years in university classrooms with students. Almost universally my students have said that they’d never had anyone like me before for an instructor (with the implication, in some cases, that one experience was enough)—though I never could see what was so idiosyncratic or unusual about the way I ran my courses.

I mentioned earlier that my Ph.D. dissertation on Li’l Abner. I decided to send it to Twayne publishers, on the advice of a friend. Then I didn’t hear from them for a year plus. I happened, by chance, to be in New York and went to see the editor of Twayne books.

“Berger,” he said, as I sat down on a chair in front of his desk. “What are we going to do about your book? I don’t remember.”

He reached behind him and pulled my manuscript from a bookcase. He opened the manuscript and looked at a piece of paper in it.

“We’re going to publish it,” he said.

I can remember how thrilled I was. I thought, at that time, that publishing a book would make a big difference in my academic career, and also how little trauma it took to get a book published. Maybe that success encouraged me to continue writing, because after five or six years I found myself with six books. I never thought I’d write many more books, but somehow I got ideas for new books and before too many years had passed, I had twelve books. Then, not too much later, somehow I had twenty-four books, and then forty books. I can’t explain it. From my list of books you can get a sense of my interests. One reason my books were published is because they are “accessible.” That means I didn’t throw fancy jargon around or write in the style that many graduate students learn, which is highly stylized and often quite pretentious.

Publishing books is often quite aggravating, for a variety of reasons. Copy-editors go over your manuscripts and ask millions of questions. When you’ve gone over the page proofs and taken care of the index, you find that there are frequently long delays at the printers. Sometimes your editors make all kinds of suggestions, and they often send your manuscripts to professors who make other suggestions and at times really want you to rewrite the book the way they would have written it. Or who trash the book. Here’s a jointly written review of my Mass Comm Murders manuscript that shows what I’m talking about. I don’t know the names of the authors of this review:

As written we are hard pressed to think of any courses for which this book would be value added. It would confuse rather than clarify. In contrast, we think that the edited book that Haddley-Lassiter [a character in my mystery who strings together quoted passages from famous theorists in a proposal for a book] would be a good companion volume to any Mass Communication Theory text...we cannot think of a media and/or theory text that would be enhanced by being used with Murder Go Round [the original title for my book].”

The review then concluded that I should rewrite the book along lines the authors suggest and come up with a completely different book:

Such a rewrite would require Berger to start over. As it is now, the narrative in no way elucidates theory—it’s simply a fairly clever story with fragments of theory thrown in rather haphazardly.

Reading a manuscript review like this helps explain, I think, why bumping off professors can be therapeutic. (The book was published and is doing quite well, incidentally.) And this review is not the most negative review I’ve ever received. Someone reviewed one of my books, in a Canadian journal, by writing “How do you review a book that never should have been written?” I should point out that sometimes you get valuable suggestions from the reviewers to whom your editors send your manuscripts. For example, an editor of my first mystery, Postmortem for a Postmodernist suggested that I use a quote from a prominent postmodern theorist before each chapter. That really helped me and I used quotations before each chapter in all my other mysteries.

Figure 16: The Mass Comm Murders

I like to illustrate my own books, so I’ve been fortunate to find some publishers who have made excellent use of my illustrations. There is a momentary thrill you get when your publisher finally sends you a copy of your new book. This is followed by speculations about how the book might be reviewed and doubts about whether anyone will read it or any professors will adopt it for their classes. When I get a new book I look the book over, scan it for typos, and then I put it in my book case. Then, it’s on to the next book. That’s because by the time one of my books is published, I’ve spent so much time working on it—going over the manuscript many times to get the writing just right, going over the copy edited manuscript pages, proofreading the page proofs, making the index—that I’m sick and tired of the book...but very happy that it has been published.

It’s always interesting for me to watch people in bookstores. They pick up a book, glance at the front and back cover, look at the table of contents, and put it down, all in about a minute’s time. When I think of the amount of work involved in writing the book and publishing it, I always marvel that books are treated in such a cavalier manner. But, of course, I’m speaking from the perspective of a writer.

There is something else I should mention. Unlike many authors who write textbooks (I don’t think of myself as writing textbooks but as writing scholarly books that are used as textbooks), I never write queries to publishers about books I plan on writing. Instead, I write the book—because I’m interested in the subject, because I want to find out more about it, and because I want to discover what ideas I had that I never recognized until I started writing. And then I go looking for a publisher.

So every book of mine represents a lot of work that may not pay off in getting published. Now that I have a substantial number of books that have been published, writing a book before getting a commitment from a publisher isn’t quite as risky as it used to be. But it still is a risk and I must confess that I’m not always successful in publishing books I’ve written.

And books don’t always have the “payoff” you think they’ll have. In my 35th journal, Relations II, I write:

So here I am with my seventh and eighth book coming out and it has meant nothing, so it seems. No job offers, no help in getting grants, no help at school (in fact, it has hindered me). It has given me a lot of psychic income and ego strength, however...and some regular income, as well.

One problem with writing oneself into existence is that you face a problem when you stop writing. Will you cease to exist? That may suggest that when I complain to myself, in my journals, as I do over and over again, that I haven’t got any ideas for new books, I’m really alluding to an existential dilemma that I, and all writers, unconsciously recognize. Maybe we can modify Berkeley and say that for writers, “to be is to be in print” or “to be is to be reviewed,” or some combination of the two.

Postscript

Figure 17: Photograph of Arthur Asa Berger

This article contains material about writing from my memoir, Writing Myself into Existence. I now have a manuscript on myth and media being considered for publication by a publisher. I’ve also been asked to write a book on global icons. So it looks like I’ve solved the problem of find a way to continue to exist for a while longer.