Victor Del Hierro, Michigan State University

Daisy Levy, Southern Vermont College

Margaret Price, The Ohio State University

(Published April 20, 2016)

Introduction

We are in the auditorium of the Kellogg Center at Michigan State University, on a cold October day, listening to Malea Powell invoke the indigenous people of the land on which we are standing and sitting, hearing her call us into the space of cultural rhetorics: “an orientation to a set of constellating methodological and theoretical frames” (CRTL). In this room are scholars and teachers whose theory comes from hip-hop, theater, disability, feminist public art, decolonialism, science fiction, and beadwork. Our ability to meet one another in this space has been thoughtfully enabled: in various rooms there are food and drinks, networking space, quiet space, an art gallery and maker space, soft couches, reminders and information on being fragrance-free, gender-neutral restrooms, free Wifi, a designated hashtag, an ever-present staff of assistants ready to answer questions. This is, in short, a designed space. This is a space designed to offer us access to each other.

Despite all the care, access is out of balance,1 as it always is. Only a few presenters provide copies of their presentations, thus cutting some disabled participants out of the conversation.2 During a session, several white people in the audience speak over the scholar of color who has just presented, seemingly oblivious to the historical loudness of their voices and the way their efforts to interrupt each other have silenced everyone else. Our efforts to meet in this space are characterized by constant movement, flexibility and improvisation as well as loss of balance, falling.

In this piece, we (Victor, Daisy and Margaret) offer a theory of allyship for those who are part of cultural rhetorics.3 To be clear, when we say “allyship,” we are not talking about celebrating diversity in a facile or fixed way. “Institutional diversity discourse,” Stephanie Kerschbaum has written, is pervaded by a “fixation” on difference (6; see also Ahmed), through which identity differences are treated as static bits of currency to be traded on a board—or totaled up in an “Oppression Olympics” game (Elizabeth Martínez; see also Tobin Siebers 28-30). Moreover, we will not be offering a checklist of desirable behaviors; such a move is critiqued by Tara Wood and her co-authors as one that “isolates disability [or another marginalized identity] within the body or mind of one student in one class, freezes disability as a set of symptoms rather than as a social process” (147). In sum, this essay does not attempt to provide a definitive answer about how to practice allyship across cultural difference. Rather, it’s a call for those building cultural rhetorics to think and communicate explicitly about how we will orient to each other’s differences and affinities, in the spaces where we come together, in our scholarship, and in the ways we support one another in the larger (and often hostile) academic world. Allyship is not a state to be achieved, but a community-based process of making. We want to push cultural rhetorics to think seriously about what it means to negotiate difference in the spaces we create, and communicate explicitly about what our practices of allyship should look like going forward.

Our theory of allyship is grounded in our own experiences and stories: Victor from being a student of color in the academy and Hip Hop, Daisy from dance and injury, and teaching bodies and movement, Margaret from experiences of whiteness, disability, and queerness. In the sections following, we discuss the notions of margins and centers as both metaphor and literal spaces that need troubling, an embodied and relational basis for allyship, and emotional labor and its intersectional qualities of empathy, harm, and pain that allyship necessitates. Ultimately, we argue that cultural rhetorics gatherings (in-person, digital, scholarly, social, activist) must include deliberate spaces for negotiating allyship, both the moments it fails and the moments it is re-made in our everyday encounters. We cannot assume that such negotiations will take place around the edges of Cultural Rhetorics work, or will happen automatically. Rather, we as a disciplinary community will have to hold space for such encounters, remembering that they are a critical part of the ongoing practice of cultural rhetorics.

Margin/Center, Space and Situatedness

“I’m not on the outside looking in, I’m not on the inside looking out, I’m in the dead fuckin’ center looking around.”

—Kendrick Lamar

(Victor) I have been in this situation before. All I can do is tweet. I am standing here in the back of this room literally staring at a panel of three people. The person in the middle is a scholar of color. On each end is a white scholar. Physically and in the questions the audience asks, the student of color is in the center yet his panelist will not stop talking for him. I should say something but I don’t want to be rude.

Figure 1: Screenshot of a tweet reading, “Really hoping these white people will let the scholar of color talk, instead of talking at him #crcon.” It is dated 1 November 2014 at 10:57 am and marked with four retweets and eight favorites.

Hopefully people will see my tweet.

Allyship starts with an orientation and the recognition of difference. It is a negotiation of being both aware that you are part of a social structure that is perceived as a majority or normative while trying to support those that your social structure is othering. An interplay of the contradictions of centers and margins, theorizing allyship leads to a consideration of how space is organized and furthermore pushes us to disrupt the idea or metaphor of the margin. Especially in reference to allyship in the academy, margins are frequently used as an important metaphor for orientation. Discourses in the field will refer to “margins” or “marginal” people, as a means to map out where these scholars and scholarship are in relation to what is perceived as the center. This practice of mapping allows for certain assumptions to be upheld. In a vacuum and most optimistically, it allows for a discipline to maintain a perceived sustainable center that aids in orienting scholars and scholarship to each other. A discipline will rely on this center to form its identity and establish a level of legitimacy.

However, the establishment of a margin in practice is always about maintaining what is not the center. Works on the margins are never meant to expand the center; in naming something or someone marginal we are reiterating and confirming their place in the relationship. Within academia and outside of it, we encounter examples of how marginalization operates as a colonizing tool to make one believe that a static center exists. Because that center most often represents a white supremacist heteronormative ableist ideal, everything outside of that is marginal.

As we are complicit in this established center, we forget that this metaphor is just a metaphor. Those of us who are placed in or identify with the margins begin to believe that we actually live there. We start to embody that position and constantly think about our status as marginalized. In and out of the academy we are constantly surrounded by the practice of marginalization. Watching from the back of the room, it would have helped if I would have spoken up. It would have helped to know if I called you out, we wouldn’t have to avoid eye-contact. It would have helped to know that speaking up would not totally shut down the discussion, silencing everyone. It would have helped if I was not so used to stewing in silence cause I always feel like I am the only one who is noticing this happen.

Disrupting this margins metaphor as it is currently manifested becomes important for two reasons: reclaiming ourselves as the center of our own experiences and understanding that the center of a discourse can be fluid. Fluidity comes after we understand how we are the center of our own experiences. Being aware of this allows us to become comfortable in spaces where we are not the center but acknowledge that we have a relationship to the center. Being conscious of our relationship to a discourse allows us to think about when we should center ourselves or when we should move to the margins.

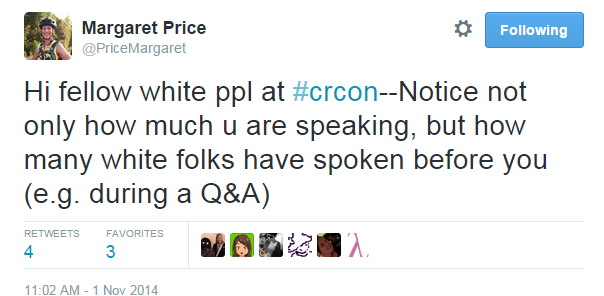

Figure 2: Screenshot of a tweet reading, “Hi fellow white ppl at #crcon—notice not only how much u are speaking, but how many white folks have spoken before you (e.g during a Q&A). It is dated 1 November 2014 at 11:02am with four retweets and three favorites.

This re-evaluation of the margins metaphor pushes us to remember that centers and margins are fluid. No(body) actually lives in a margin. As allies, as we start to occupy similar space, we have to learn to think about what spaces privilege whom, and why.

In earlier literature on allyship (from the 1990s-2000s), ally work tends to be imagined in a linear fashion. “Conversations” across cultures are generally imagined to be dyadic, involving only two people, rather than taking place within spaces or communities. They also tend to be imagined in ways that minimize the complex cultural histories and affinities that people bring to their exchanges. Rather than imagining potential allies as already embedded in overlapping, embodied communities and cultures, much of the literature tends to identify a single characteristic of an ally (e.g. “a white ally”) and imagine them in a context with one other interlocutor—for example, “a roommate or close friend of a different race” (Reason et al. 539). This sort of stripped-down understanding of allyship is often accompanied by checklists which, while well-intended, give the impression that one can follow a series of ten steps in order to avoid racism or sexism or ableism. Such an approach makes allyship into a recipe, and implies that the ingredients are stable and the outcome easily determined. (Just add an egg, heat, and serve!) Finally, the items on such checklists are often unhelpfully vague—for example, “Intervene when you hear someone make a racist joke.” What does “intervention” look like, in a specific context? What about the messy and painful outcomes?

More recent work, especially in contexts that center people of color and/or disability justice, imagines allyship as an ongoing practice emerging through collective action. An example is Mia Mingus’s account of the Creating Collective Access action in Detroit. Mingus describes this group’s interdependence as requiring constant re-negotiation and check-ins, as well as collaborative efforts to locate accessible restaurants, bathrooms, and taxis. She notes, “I watch how [the world] is constructed for us [disabled people] to move with non-disabled people, instead of each other; and how it discourages folks with different disabilities from moving together.” This emphasis, on different, is the crux of Mingus’s point. It’s not hard to imagine disability access if everyone needs the same thing (say, an ASL interpreter, or a ramp), but the project becomes much more complicated when access needs circulate around a wide variety of disabilities, genders, races, and classes. Negotiating allyship in such contexts can only occur through time, communication, and specific practice. A checklist is not an option.

Theorizing allyship means theorizing the spaces in which allyship can occur. We argue that being allies to one another in cultural rhetorics will mean understanding—and feeling—what it means to interact in a space where every person is coming from multiple, overlapping communities and identities; where no one occupies the center or the margin all the time; and where privilege and oppression overlay one another like stitches in a knitted shawl. This situation—in which location is both crucial to understanding one another, but also never fixed in place—is easy to point to but difficult to navigate in practice. Everyone will make mistakes. The critical question is not “How do I avoid ever making a mistake?” but rather “What do I need to do after I make a mistake?” In other words, we need to get away from the notion of maintaining a certain position and instead start thinking about movement.

Embodiment and Relationality

(Daisy) I’m sitting in an audience at a CCCC panel, March, almost 2 years ago. I’m knitting and listening to people talk about queerness, about asymmetry, about bearing witness to wounds, about the epistemology of wounds. My own curiosities about bodies and how they heal, or don’t, how they move, pattern, disrupt, and sustain are spilling around in my brain. At the time of this story, I have arrived at the C’s pretty tired, nearly at the end of my second year of faculty life at a small liberal arts college. In between the spilling out of witness-bearing, epistemology, and bodies, are the other things: the student who showed up in my office to offload stories of physical harassment at work last week; the empty provost position and confusion about who would be signing travel funding requests now; the instructor who doesn’t want to be observed and won’t answer my emails about a conversation; the papers to grade.

More than a tirade of all the work we all have to do all the time, I mean to highlight that it was all there, all at the same time. It’s true that I was exhausted, and frustrated, and a little scared—that this is what my life would always be like. It’s also true that I was hearing the panelists’ stories and theories about what queer rhetorics has meant, could mean, should mean, and I was feeling hopeful, intrigued, focused.

Then Franny Howes said this thing about balance. She said, “Balance is overrated.” She said, “Let queer rhetoric topple you over.” I put down my knitting, and typed in my notes: CALLING FOR IMBALANCE.

Where we have been talking about allyship, mentoring, about margins and centers, I insert this question about balance to a very specific point. I agree with Howes: Balance is definitely overrated, and I would go a little further, to insist that it’s a fantasy, one that is often deeply tied to imperial desires for expansion, for conquest. Consider as some examples: the many panels and articles on achieving balance between “work” and “life” (or “parenthood” or “health” or “happiness”) at conferences, on our campuses, in the academic and popular press; the fitness industry’s fascination with re-packaging yoga or tai-chi for the western, white, capitalist body. Balance is so often discussed as a thing that must be achieved, a location that can be sought out and mastered, a place you can get to, via checklist perhaps. But the experience of balance is more like a series of movements, of fallings and rightings. It’s more accurate to describe balance as a continuous practice of orientations and re-orientations within gravity among other living things, which are also always orienting and reorienting. Here is the point on which we pivot, for an embodied approach to theorizing allyship: there is no one location, no one way to recognize alliance; it’s messy, and it’s a foundational and continuous practice all day, every day. As we have already suggested, everybody makes mistakes; everybody falls.

In movement education, balance is almost universally understood as something that is constantly moving, definitely not identifiable, not a destination. While it may be something we look for, we are also immediately aware of how easy it is to lose it. More appropriately, we may have a sensation of balancing, and then almost immediately, we have the sensation of falling. Take as one example the act of putting on pants, especially from a standing position. When we lift one leg we are probably moving back and forth and side to side, maybe even bobbing up and down on our supporting leg, or in our torsos. This movement occurs if we are standing or sitting, it occurs a thousand or more times a day, actually, as the same one taking place every time we take a step, turn in our seat, roll over in bed.

But balance means more than standing on one leg, or sitting on one hip. It could suggest the way we want a combination of strength and flexibility. We seek out balance around a particular joint—the knee, for example—in terms of the bones involved, the ligaments, the bursa, the cartilage, the circulation, the range of motion, the weight bearing capacity, the ability to support or transfer energy. In every case, balance is just as fluid, even wobbly. Also, any given body’s relative proportion of strength to flexibility will not stay the same over time or in different moving situations. The same goes for balance around a joint. This persistent multiplicity means that “balance” and “the center” are necessarily changeable, depending on which kind of body you’re talking about, what the body is doing, where the body is—the rhetorical situation of the body.

If balance is more accurately understood as an unfolding experience, which is practiced, rather than something that can be named and fixed,4 and “center” is more akin to a phenomenon that changes and shifts, according to multiple events and experiences, then to describe one body’s relationship to other bodies is similarly difficult to pin down. We are talking about putting on your pants, as much as we are talking about building spaces that reconcile the shifts and turns as allies, rather than as margins and centers, or overs and unders. Allyship occurs between and among bodies, with real, felt consequences.

Allyship is a relational act at its very foundation. Earlier in this essay, we’ve claimed that “understand[ing] how we are the center of our own experiences [...] allows us to become comfortable in spaces where we are not the center but acknowledge that we have a relationship to the center. Being conscious of our relationship to a discourse allows us to think about when we should center ourselves or when we should move to the margins.”5 We have a relationship to the center. When should we move to the margins? It’s a question of conscious re-orientation, and not only to the discourses we are engaging or listening to, but to the other present bodies, and their own re/orientations. It sounds and is complicated. It sounds potentially chaotic, even, with so much moving around. But here is our point. It’s exactly all this moving around that is taking place, and we need only look at how our bodies work to see how it happens, and to understand how it holds together. The three of us are trying to point our scholarly community to what goes wrong, and what would have helped. The chaos and the mess, the perpetual falling and righting—this is what helps.

A physical body’s experience of im/balance comes as much through the coordination and movements of that one body as it does through other forces: gravity, sensory stimulus, other bodies. Simply put, being able to balance (or fall, for that matter) is a complex mechanism of inter-related events. Of those events, most of them are ones we cannot control in our own bodies. Just as we cannot control them, these other forces are exactly the kind that connect us—to each other, to the ground, to the planet. Again, from movement education, we offer this, from Mabel Todd: the way a person understands her or his relationship to the universe occurs at the level of the bones, those bones’ relationships to each other instigate postural patterns, which then allow for neurological transmission, which engage muscular support and movement, which feed the body’s cognition—about place, about relationship, about the universe. Todd’s ultimate claim is that what we understand from such a connection includes the distinction between our self and other selves, or our self and the rest of the world, but also, importantly, our relationship to the world, to other bodies in the world.6

At this point, the question of im/balance spreads out, the implications being so much greater than whether or not we will stay upright ourselves, but what will happen to the whole structure. Will our falling result in crashing into someone else? What will we land on? Recall the image of the many layers of privilege and oppression as stitches in a knitted shawl. And now, consider the possibility of im/balance and re-orientation as critical elements in functional alliance; re-orientation including the many instances in which we fundamentally change our relationship—to other bodies, to gravity, to discourses, to spaces, and im/balance including re-centering, wobbling, perhaps even crashing and falling, only to right oneself with a new sense of the ledge. There are myriad cases of such re-orientations, the tweets we’ve shared in this essay itself, as one example. These calls and responses, from scholars of color and white allies indicate the need to make unreflective practices visible, and calling for accountability of all present bodies. They also indicate a willingness of all present bodies to mark themselves in public, as part of a larger effort, and in relationship to each other. But you don’t have to tweet to reorient yourself. This essay itself is an example of how allyship works as a series of shifts. Consider the ways we use discourse to negotiate the multiple relationships of self and language. For example, which pronouns do you use, and when? Do you write collaboratively, and if you do, how do you do it? These are not easy decisions to make: again, there’s no checklist. But attending to questions such as these, in our writing, our teaching, our research, our service commitments, our public behavior, all contributes to a dynamic sense of who you are, where you are, and who else is there with you.

We fall, or we move to the margins, and what we used to see as the center, is now to the right or left. The same is true for what used to be up or down. Obvious, maybe, but perhaps what is less obvious is the overall effect this has on the system that is your body. All these changes mean that your nervous system can no longer rely on what it assumed to be true, what it assumed to be natural, based on the patterns your body has practiced over and over again, in your customary orientation to gravity.

Considering your own individual orientation to gravity connects you into a system that is much larger than your self, and much larger even than a relationship with another person. Focusing on your bones, and your body and these things’ relationship to the ground, to the sky, through gravitational force allows you to feel the ground under your feet, and the way the ground participates in your uprightness, or whatever orientation you presume. This participation connects you to the planet, in a way that suggests you are part of it, not on top of it, and not separate from it. This participation requires your body, but not yours alone. To practice alliance as we are theorizing it here requires that we each persist in our own reorientations—to be aware of the ways we are in relationship to the many constellated centers ever present in cultural rhetorics.

To be aware of it means more than noticing it, more than nodding in affirmation. It means we must attend to the force we muster in our own embodied and discursive lives, how that force is being distributed through the rooms we inhabit, and the bodies we engage with. Indeed, we must remember that our own im/balances, while inevitable, are also not inconsequential. We are not merely susceptible to the force of gravity; we participate in it as much as it acts on us.

Empathy, Silence and Harm

(Margaret) I am walking with my partner, holding hands, on a public street in Atlanta. It’s dark and cold, early December, but the lights strung outside are festive and we are laughing, full of restaurant food, on our way to a friend’s concert. As we step into the orange glow of a corner streetlight, a truck spins around the corner to our right, and a large plastic cup sails from one of its passenger-side windows. A shower of ice and liquid splashes across the fronts of our coats and scarves, the cup strikes my shoulder, clatters to the sidewalk. Our hands jerk apart and we stare after the truck as it careens away, taillights flashing. An unidentifiable liquid drips down our bodies. A scatter of ice lies flung in front of us like something broken.

One of many layers of pain involved in such an incident is that you never really know why someone might throw a drink at you on the street. Maybe it wasn’t because you appeared to be a lesbian couple holding hands in public.7 Maybe they were just drunk and being assholes. Maybe it wasn’t that bad; it’s not like either of us is hurt. Or maybe they’re coming back around the block to find us again. Hands separated, we walk quickly to the theater, wipe off with paper towels in the bathroom, and sit through the concert as our pants slowly dry.

Another layer of pain enmeshed with the simpler pain of a thrown drink is my history of post-traumatic stress disorder, past abuse, panic attacks. For a week afterwards, I don’t tell anyone about the thrown drink, though the truck’s taillights flash in my dreams at night. Finally, I post the story to my Facebook page, deliberately breaking my silence, pushing myself to tell the story just as I might push myself to begin a difficult writing task for work: this needs to be done.

Among the responses of sympathy and outrage are a few that refer back to the commenters’ own experiences of thrown objects. For example, a straight friend who is also a road skater notes that people sometimes throw things at him from cars when he is out skating alone. Predictably, I feel annoyed and frustrated at these and other comparative responses; and predictably, I say nothing, both because I know the comments are well-meant, and because I just don’t have the energy to get into it. Quietly, I cross this friend off my private list of straight/abled people who “get it,” with whom I am willing to risk my more complicated stories.

The theory of allyship we’re developing here is deliberately intersectional. It insists that there is never “a” white person, or abled person, or straight person, interacting with “a” person of color, disabled person, queer person. As the previous sections indicate, any interaction of two or more people also brings together their overlapping communities, their always-shifting embodied presences, their experiential and cultural histories. This theory of allyship rejects the notion that identities are fixed in place, picking up instead the image of constellating, which enables “multiply-situated subjects to connect to multiple discourses at the same time, as well as for those relationships (among subjects, among discourses, among kinds of connections) to shift and change without holding a subject captive” (CRTL). Further, our theory insists that the affective dimension of allyship is critical. Allyship as it is practiced in cultural rhetorics must follow emotional logics as well as factual ones, and it must take into account the costs—and advantages—of emotional labor.

The “emotion” we refer to here is not guilt, sympathy, or the kind of facile empathy that functions reductively (for example, “My oppression as a disabled person gives me unique insight into the oppression that people of color face”). Nor is it, as Trish Roberts-Miller argues, “what a superior feels for a submissive inferior,” a move that actually “maintains the hierarchy” (“Tragic Limits,” 697, emphasis in original). Rather, the emotion we refer to here is a form of affiliation—what Sami Schalk, writing about disability allyship, has called “identifying with":

I use identify with to mean having acknowledged and prioritized political and personal connections to a group with which one does not identify as a member. To identify with means to feel implicated by the culture and politics of another group and seek to better understand this link. While to identify with could be understood as analogous to being an ally, I contend that there is something more personal, sustained, and affective about it. Identifying with is a careful, conscious joining—a standing/sitting among rather than by or behind a group—which seeks to reduce separation while acknowledging differences in privileges and oppression.

Schalk’s use of “identify with” could be mis-applied in its colloquial sense, which is typically glib (saying as a man, for instance, that one “identifies with” women based on some other form of oppression). However, her explanation of what her theory of identification means in practice contains much that is useful to cultural rhetorics, particularly her emphasis on the sustained, affective, and embedded nature of the connection. As Schalk describes identifying-with, she is outlining a kind of relationship that can only evolve over time, and requires investment from all parties involved.

The next question, then, might be this: What sort of communication occurs when participants in a space are “standing/sitting among” each other? Too often, it means someone gets drowned out, dismissed, tokenized—in a word, marginalized. And too often, the one doing the drowning-out means well. They’re good at heart. They probably think of themselves as an ally. They belong to what Roberts-Miller calls “the culture of good intentions” (“Hate Rhetoric”).

One classic way to perpetrate the culture of good intentions is to compare or conflate oppressions—for example, to claim that “all women” share an essential experience of oppression on the basis of sex. In Rhetorical Listening, Krista Ratcliffe examines an extended instance of such comparison, in which Mary Daly claimed that she and Audre Lorde, despite their different races, shared a “transcultural and transhistorical” form of exploitation under patriarchy (Ratcliffe 80). After some private exchanges, Lorde published an open letter in response, identifying the pattern by which white women erase differences between their own and black women’s experiences—claiming, in effect, that white women’s experiences represent those of all women. Daly’s failure to engage Lorde, Ratcliffe argues, could have been mitigated by a practice Ratcliffe calls “metonymic listening.” This form of listening does not assume essential commonalities (e.g. that all women have the same experience of misogyny) but rather notes when and how experiences (stories, histories, outcomes) are associated or juxtaposed (98). Through metonymic listening, it is possible for people of different cultures to reach a place of affiliation rather than always reverting to one of two extremes—either “Since we are not the same gender / race / ability / class / etc., I cannot possibly have any idea how you feel” or “Since you belong to Oppressed Group A and I belong to Oppressed Group B, I have full understanding of how you experience your oppression.” It offers us a more dynamic path from which, and along which, to move.

However, a point arising from all our stories must be returned to more carefully: Pain, loss, and giving up. Injury. Victor’s story about sending that Tweet; Daisy’s account of falling; Margaret’s story of street harassment—these are all experiences of pain (though not only pain). Lorde’s letter to Daly states that “I had decided never again to speak to white women about racism” (qtd. in Ratcliffe 83). That painful, self-protective kind of silence—which Lorde broke by publishing her letter—is re-enacted all the time, within cultural rhetorics as well as outside of it. We silence each other all the time. We cause injury to each other all the time. And we—“we” here referring to those participating in cultural rhetorics—must contend with that stark fact beyond simply nodding and agreeing, in vague terms, that we ought to engage in some reflection.

As we think about pain and the silences it can cause, we are reminded of Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s writing on the importance of stillness and retreat in activism, as well as Ernesto Martínez’s work on joto passivity. Silence can be self-protective, healing, and/or resistant (see Cheryl Glenn; Krista Ratcliffe). But it can also be the sign of someone giving up on communication. We—the “we” of cultural rhetorics—will need to think carefully about our silences as well as our conversations. We need a mechanism to call one another out, and to do so in ways that distribute the emotional energy of doing so. It would have helped if someone else on Margaret’s Facebook thread had chimed in to say, “Hey, she’s talking about queer-bashing—that’s not really comparable to cars harassing skaters on the road.” It would have helped if the commenter had found a way to say “That sucks and I’m glad you’re okay” rather than attempting a well-meant comparison. It would have helped if Margaret could have said, without provoking defensiveness, “Please shut up.”

The challenge of “metonymic listening” is that there is no blueprint for it, no list of rules to follow. While we can easily say that eliding difference (“My oppression allows me to fully understand your oppression”) and retreating into incommensurability (“I have no way of understanding your experience, so I consider myself exempt from engaging with it”) are both unhelpful, there is a vast terrain—a “borderland,” Gloria Anzaldúa might say—between those extreme options. Offering solidarity on the basis of association can mean any number of things. Sometimes it means just shutting up. Sometimes it means speaking out, to and with others who share a similar history of privilege. It may be helpful to think of times in your own history that you’ve wished someone else would just quiet down and let you speak to your own experience. Especially in culturally unfamiliar territory, you might ask yourself, What would I value from a man right now, if he were in a roomful of women? … or What would I value from a straight person? a white person? an abled person? Often (though not always), you may find the answer to be: Quiet down. Let go of your own agenda. Look for the times when you are needed.8

We cannot discount the importance of making emotional connections across different cultural locations; these sorts of “affective investments” (see Alison Kafer and Eunjung Kim) are a necessary part of cultural rhetorics. Kristie Fleckenstein has written that empathy is “the glue by which communities adhere through just action” (707). But Fleckenstein adds that empathy must be accompanied by adequate “critical” work, through which members of communities develop “new habits of mind and action in response” (713). And there, we find, is the rub: How shall the cultural rhetorics community enact such work?9 Especially, how shall we do so in spaces already pressed for time, space, and resources—as cultural rhetorics is? In the next section, we offer some provisional thoughts on this question, but we also mean to offer the question itself to those engaged in cultural rhetorics. How shall we enact the necessity of communicating, and feeling, across our many differences? Go.

NO FUCKERS: Some thoughts about next steps

(Victor) We are back in the auditorium of the Kellogg Conference Center. The conference is coming to a close and we have gathered to discuss what is next for cultural rhetorics. The room feels good. The room is loud the way a dinner party is loud. Malea Powell asks us to get together in groups to discuss what steps or ideas we should start to implement. After some time each group sends a representative to report out.

I make my way to the front to wait my turn. I look over my notes to ensure that I represent everything my group talked about. Angela Haas goes up to speak and I am next after her. Suddenly I hear Angela say something to the effect of, “We will not let fuckers publish in our journals, speak at our conference, or represent us in the field!” The crowd reacts in cheers and applause. In that moment there was no need to elaborate who the “fuckers” are. The statement was powerful and indicative of the vision many of us have for cultural rhetorics.

There was urgency in this statement that galvanized an attitude. Haas’s insistence on not tolerating “fuckers” in the academy reminds us of the ways that academia will continue to allow those who benefit from and participate in oppressive structures to flourish. Although this reference might seem less understandable outside the context of the gathering at Cultural Rhetorics, essentially, it was a reminder that our cultural practices, our writings, our theories, have long been appropriated and/or dismissed within the larger institution of rhetoric/composition, and within academia more generally. That was the reason we gathered together that weekend in October: we needed a space. Despite the many good intentions of our allies within rhetoric/composition and within academia, we still needed a space to talk to each other. This is also the reason that this essay is framed so specifically in the time and space of the first cultural rhetorics conference, and the reason it is not framed as a lesson for the majority cultures of rhetoric/composition. Without a doubt, rhetoric/composition can learn from this discussion of allyship, and we hope many readers will. But at this moment, we are speaking for ourselves, to each other—because we need space to do that too. Put bluntly, we are not here to educate rhetoric/composition as a whole. But we are speaking publicly because this essay in itself is an opportunity for allyship. How will you listen? How will you respond?

As we continue building the cultural rhetorics community, we have to remember that our actions and practices manifest themselves as the policies that govern how our collective works together. By being open and transparent about our refusal to tolerate those who are unwilling to question their own privilege, we can start to think about ways to support each other. The phrase “No Fuckers” is still just as abrasive as when Angela spoke it, and we use it here to ask for deliberate action towards confronting the ways we are fuckers to each other.

Looking again at earlier work on allyship, a frequent term used is “uncomfortable,” as in, “Confronting your own racism / sexism / homophobia may be uncomfortable.” We disagree. We would say, rather, that confronting the ways we perpetrate racism, ableism, and other -isms upon each other is painful. And it hurts to absorb those moments of micro- or macro-aggression, coming from one’s own colleagues, and to make the decision yet again: Do I educate, do I shout, do I cut my eyes, do I flee? This labor must be noticed, acknowledged, honored. We must make space for it.

How does a collective like CR-CON engage in the “no fuckers” rule? How do we make decisions? Keep ourselves safe? Settle in-group conflicts? Support each other? There are many models out there (e.g. consensus-building; peer collectives), but we will have to be mindful about how exactly we plan to go about doing this.

We promised at the beginning that we would not resort to a banal checklist of things to do; instead that we would try to theorize this space richly, in ways that could help us continue to build and design spaces in which cultural rhetorics could both recognize the hostility of the academy and to disrupt it. There’s nothing easy about it, no list that ensures “safe spaces,” nor clearly identified “fucker-free zones.” We would like this conversation to become central to future Cultural Rhetorics gatherings. In addition to dedicated spaces for refreshment, art, making, quiet, and networking (all of which were present at CR-CON14), we need dedicated spaces of affinity, spaces for working through dissent and issues of cross-cultural competence and spaces for retreat with our fellows. We must start building the infrastructure for sustainable alliances and community.

(Victor, Daisy & Margaret) CR-CON’s business meeting has ended. People are milling about, gathering things, chatting with each other, laughing, nodding to each other, beginning the process of transitioning from this space into our other spaces, institutional ones, home ones, traveling ones. We are all of us, individually and collectively, wondering what the next steps are, excited, nervous, curious. Margaret and Victor are chatting at the back of the auditorium, and Daisy joins on her way out. Margaret is speaking about allyship, about how we—we, in cultural rhetorics—are going to need to pay attention. She asks, “would you—would you want to put something together about this? Maybe think it through together?” Back home, we begin to write.

- 1. The theoretical frame of “balance,” developed further below, is drawn from Howes and Levy.

- 2. Providing notes or copies of presentations, including online, can provide access for attendees in many positions, including those who are deaf, those with audio-processing difficulties, those who may find it easier to follow language in written than in spoken form, and those who cannot attend. Jay Dolmage has created a video to explain why he posts his conference notes and papers online, with acknowledgement of concerns such as plagiarism. It can be found on the “Composing Access” website: http://composingaccess.net.

- 3. While we hope that the wider field of rhetoric/composition will be eager to read, think about, and respond to this essay, we also emphasize the need for spaces in which cultural rhetorics scholar/activists speak with and to each other. Thus, this essay is framed as a “space of affinity” that centers cultural rhetorics scholars, but is also open to others (See James Paul Gee). We develop this idea in the final section.

- 4. In the opening to this essay, we referred to Kerschbaum’s “fixing difference” as a way to problematize attempts at diversity and allyship. At this point, we are marking the idea of balance as one similarly problematic moment, calling into question the practice of stabilizing a thing that is implicitly unstable.

- 5. Given that this article is a collaborative effort, we want to highlight this moment as one where the authors are directly building from and with each other.

- 6. For more about these relationships and theories, see Mabel Todd, The Thinking Body, Lulu Sweigard, Human Movement Potential, Ida Rolf, Structural Integration, Irene Dowd, Taking Root to Fly, and Daisy’s theoretical framework for how to connect this work to rhetoric studies in This Book Called My Body: An Embodied Rhetoric.

- 7. As it happens, neither of us identifies as a lesbian; I am a queer femme and my partner is genderqueer. However, such fine points of identification are not generally available in our public exchanges—hostile or friendly.

- 8. As we write and revise this article, a number of essays are making their way around social media, in response to #blacklivesmatter, #charlestonshooting, #SayHerName movements and the related events of systemic white supremacy. We recognize this cultural moment as another instance of how our disciplinary and extra-academic lives can come together. In particular, Robin DiAngelo’s “White Fragility” may provide a useful lens for considering imbalance, re-orientation, and listening when thinking about allyship, privilege, and pain. While we do not wish to dilute DiAngelo’s argument about whiteness in particular, we suggest that the notion of “fragility” may be useful for reflection across various dominant positions.

- 9. Fleckenstein’s essay does give careful attention to specific instances in which this work is completed; and even so, it is hard to tell exactly what such actions, such as “collaboratively composing oral, visual, and print stories” entail (713). Possibly, the question “Exactly how is this done?” is a kind of trick question, demanding an exact recipe, another checklist.

Ahmed, Sara. On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life. Durham & London: Duke UP, 2012. Print.

Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1999. Print.

The Cultural Rhetorics Theory Lab (CRTL): Powell, Malea, Daisy Levy, Andrea Riley-Mukavetz, Marilee Brooks-Gillies, Maria Novotny, Jennifer Fisch-Ferguson. “Our Story Begins Here: Constellating Cultural Rhetorics.” enculturation. Web. 25 Oct. 2014.

DiAngelo, Robin. “White Fragility.” International Journal of Critical Pedagogy 3.3 (2011): 54-70. Print.

Dolmage, Jay. “Sharing Conference Papers Online.” Composing Access. Web.

Dowd, Irene. Taking Root to Fly: Articles on Functional Anatomy. New York: Contact Collaborations, 1995. Print.

Fleckenstein, Kristie. “Once Again with Feeling: Empathy in Deliberative Discourse.” JAC 27.3-4 (2007): 701-716. Print.

Glenn, Cheryl. Unspoken: A Rhetoric of Silence. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2004. Print.

Gee, James Paul. “Semiotic Social Spaces and Affinity Spaces: From The Age of Mythology to Today’s Schools.” Beyond Communities of Practice: Language, Power and Social Context. Ed. David Barton and Karin Tusting. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. 214-232. Print.

Howes, Franny. Oh Shit I'm in Grad School Presents: "Stop Including Yourself, Stop Including Yourself." Paper in roundtable at CCCC 2014 Convention, Indianapolis, IN, March 21, 2014.

Kafer, Alison and Eunjung Kim. “Literatures of Intersectionality.” The Cambridge Companion to Literature and Disability. Ed. Clare Barker and Stuart Murray. New York: Cambridge UP, forthcoming. Print.

Kerschbaum, Stephanie L. Toward a New Rhetoric of Difference. Studies in Writing and Rhetoric. Urbana, IL: NCTE, 2014. Print.

Lakshmi, Leah Piepzna-Samarasinha. “A Time to Hole Up and a Time to Kick Ass: Reimagining Activism as a Million Different Ways to Fight.” We Don’t Need Another Wave: Dispatches from the Next Generation of Feminists. Seattle: Seal Press, 2006. 166-179. Print.

Lamar, Kendrick. “Ab-Soul Outro.” Section.80. Top Dawg Entertainment, 2011. Digital.

Levy, Daisy. “This Book Called My Body: An Embodied Rhetoric.” Dissertation. Michigan State U, 2012. Print.

Martínez, Elizabeth. “Beyond Black/White: The Racisms of our Times.” Social Justice 20.1-2 (1993): 22–34. Print.

Martínez, Ernesto J. “Con quién, dónde, y por qué te dejas? Reflections on Joto Passivity.” Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies. 39:1 (2014). Print.

Mingus, Mia. “Reflections on an Opening: Disability Justice and Creating Collective Access in Detroit.” Incite Blog! Word Press, 19 July 2010. Web. 23 August 2010.

Ratcliffe, Krista. Rhetorical Listening: Identification, Gender, Whiteness. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005. Print.

Reason, Robert Dean, Roosa Millar, Elizabeth A, and Tara C. Scales. “Toward a Model of Racial Justice Ally Development.” Journal of College Student Development 46.5 (2005): 530-546. Print.

Roberts-Miller, Patricia. “Hate Rhetoric and the Culture of Good Intentions.” Cultural Rhetorics Conference, Michigan State University, October 31 – November 1, 2014.

—-. “The Tragic Limits of Compassionate Politics.” JAC 27.3-4 (2007): 692-700. Print.

Rolf, Ida. Structural Integration: Gravity an Unexplored Factor in a More Human Use of Human Beings. Ithaca: Guild for Structural Integration, 1962. Print.

Schalk, Sami. “Coming to Claim Crip: Disidentification with/in Disability Studies.” Disability Studies Quarterly 33.2 (2013). Web.

Siebers, Tobin. Disability Theory. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008. Print.

Sweigard, Lulu. Human Movement Potential: Its Idiokinetic Facilitation. New York: Dodd, Mean, and Company, 1978. Print.

Todd, Mabel. The Thinking Body: A Study of the Balancing Forces of Dynamic Man. Gouldsboro, ME: The Gestalt Journal Press, 1937. Print.

Wood, Tara, Jay Dolmage, Margaret Price, Cynthia Lewiecki-Wilson. “Moving Beyond Disability 2.0 in Composition Studies.” Composition Studies 42.2 (2014): 147-150. Print.