Dawn Opel, Michigan State University

John Monberg, Michigan State University

(Published November 18, 2019)

Awareness is growing around health equity, or the intersectional issues of race, gender, and class at play in patients’ access to—and quality of—healthcare. One area of concern for health equity is clinical trial participation, particularly for experimental cancer drug treatments. A cancer patient must not only be well connected to gain entree to a clinical trial but also highly resourced—not only armed with good health insurance, but also the means to travel far away from home for long and repeated periods of time. Often, communication about clinical trials is not freely available via public, written documentation, but instead, through informal systems of privileged relationships. Given these obstacles, how might activists respond so as to make the activity more equitable?

In order to address this question, our kit will make visible one example of the complexities of such activity, by mapping the experience of co-author John’s cancer treatment decision-making and eventual participation in the clinical trial for ibrutinib, a drug to treat Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL). Using Adele Clarke’s ecological framework of situational analysis, we analyzed data such as health and medical documents and correspondence from John’s network—those who contributed to his participation in the clinical trial, including physicians, family members, and friends who all had expertise or connections to the trial. Per Clarke’s three-fold method, we created 1) situational maps that can be used as strategies to articulate the elements in the situation and for examining the elements of clinical trial participation; 2) social world maps to create cartographies of collective commitments, relations and sites of action; and 3) positional maps as simplification strategies for plotting positions articulated and not articulated in clinical trial discourses.

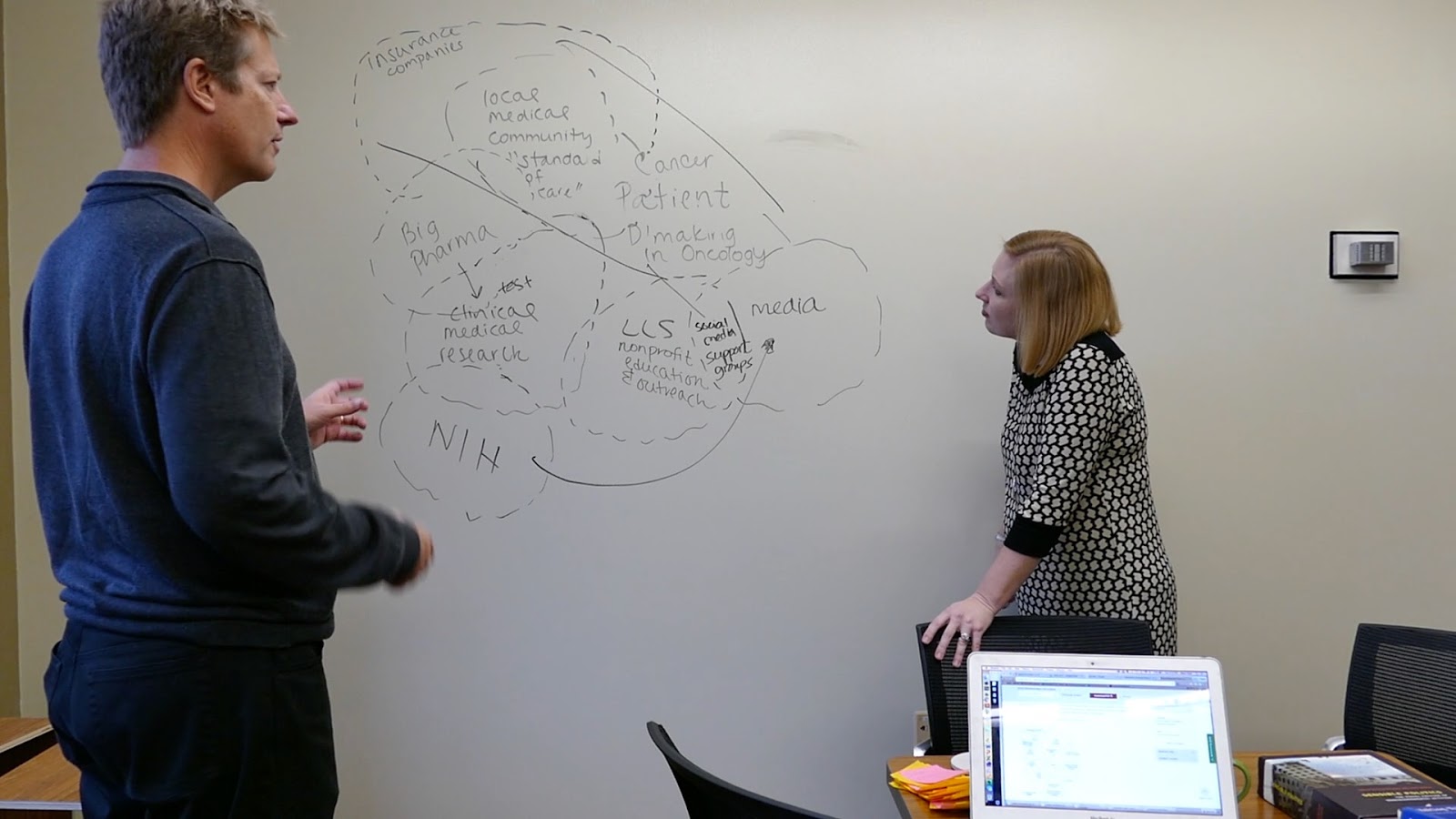

Figure 1. Mapping the MCL Cancer Clinical Trial: Step-by-Step Instructions for Mapping Using Clarke’s Situational Analysis: Grounded Theory after the Postmodern Turn (2005).

By mapping the network of the MCL clinical trial, we aim to represent visually the complexity of the literate activity that is participation in a clinical trial, and through this visibility, begin to formulate strategies for health equity activism.

In order to formulate these strategies, we weave together several maps. We apply the analysis from the Clarke method, a feminist, grounded theory approach to qualitative study of a phenomenon, to an industry approach, user experience (UX) journey mapping. Journey mapping is used as a technique for companies to visualize their customers’ touch points with their products and services, and to compare customer needs and wants against their complete customer experience. A journey map often integrates a fictional customer persona, composite customer profile of a demographic or set of attributes. John used journey mapping principles to walk us through his own journey (with his privileged persona, or position, in skillset and network) with the ibrutinib clinical trial. John created a WordPress site to document this journey.

After doing the series of situational analysis mapping exercises, Dawn and John returned to the journey map to create an activist’s journey map for health equity in cancer clinical trial participation.

Taken together, these multiple maps offer important counternarratives to the resources currently available for patient cancer treatment and demonstrate how mapping the phenomena offers vantage points left unseen in critical arenas of public and private life.

Mapping upon Mapping Clinical Cancer Trial Participation

“A problem properly represented is largely solved.” – T. E. Lawrence

This is a project borne of two rhetoricians interfacing with the health care system at the same time. John had just completed a frontline clinical trial to treat Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL) at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas. Dawn had just begun a faculty fellowship in residence at Sparrow Hospital in Lansing, Michigan. When the two compared notes, they had a conversation that looked a lot like what Harvard management professor Rosabeth Moss Kanter describes as:

Supposedly, everyone working in health care wants the same thing: to help people get and stay healthy… The problem is that everyone can have a different view of the meaning of getting and staying healthy. Lack of consensus among players in a complex system is one of the biggest barriers to innovation. One sub-group’s innovation is another subgroup’s loss of control. (Kanter)

Cancer clinical trial participation is one context within health care in which this is especially profound, and with deleterious consequences for many. Clinical trial participation, including cancer clinical trial participation, is an area of healthcare marred by health inequity. Health equity is the “absence of systematic disparities in health (or in the major social determinants of health) between groups with different levels of underlying social advantage/disadvantage—that is, wealth, power, or prestige” (Braveman and Gruskin 254). Further, a recent UC Davis study indicated that although African Americans have the highest rates of cancer, their cancer clinical trial participation is less than 2% (Dallas).

John’s experience deciding to pursue a frontline clinical trial with the drug ibrutinib (instead of more traditional treatment options including chemotherapy and radiation) was heavily influenced by his research training in Science and Technology Studies, his network of friends and family in scientific fields, and his other markers of his own privileged positionality (as a white, otherwise healthy, relatively young male), all factors that potentially contributed to entree into a lifesaving drug regimen. Upon embarking on a research project together, we began with the thought that John’s journey—from his positionality as a researcher researching his own cancer treatment—offered something of value to the conversation of cancer clinical trial decision-making. John’s research file on his own cancer treatment decision was eight inches thick and included correspondence from some of the world’s top medical researchers, pharmaceutical company executives, and national cancer patient organization advocates. From this research file, John’s own cancer decision-making network could be realized.

The Value of Mapping, and of a Kit of Maps

If John’s file and his experience can be visualized into a network, how might cancer clinical trials be mapped to reveal the multiple viewpoints within a complex system, as Kanter described? To explore this question, we turned to the qualitative research method of situational analysis, developed by sociologist Adele Clarke to “push grounded theory more fully around the postmodern turn … focusing on the situatedness of all knowledge producers, and assuming the simultaneous ‘truths’ of multiple knowledges” (Clarke 19). Clarke is influenced by “perspectives, partialities, and situatedness” and particularly George Herbert Mead’s concept of perspective:

The perspective of the organism is then there in nature. What in the perspective does not preserve the enduring character of here and there, is in motion … [T]his [is a] concept of nature as an organization of perspectives, which are there in nature… This principle is that the individual enters the perspectives of others, insofar as he is able to take their attitudes, or occupy their points of view. (Mead 1932, qtd. in Clarke 7)

It is more important now to understand the concept of perspective than ever before, particularly in the American healthcare system. Beginning as early as the 1950s, the medical industrial complex has been able to assemble a network of relationships across the social world of patient, doctor, clinic, research laboratory, government agencies, and the media to compose, design, and circulate representations of knowledge for its own benefit. For example, the manufacturers of the drug now largely responsible for the opioid crisis have created their own social world:

The Sackler empire is a completely integrated operation in that it can devise a new drug in its drug development enterprise, have the drug clinically tested and secure favorable reports on the drug from the various hospitals with which they have connections, conceive the advertising approach and prepare the actual advertising copy with which to promote the drug, have the clinical articles as well as advertising copy published in their own medical journals, [and] prepare and plant articles in newspapers and magazines. (Keefe)

This is one strand of a general process called reflexive modernization. This process integrates specialized knowledge production by particular actors in the reshaping of our social worlds—abstracting the ways that expert knowledges are embedded in systems and are then taken up in the lifeworlds of individuals. Reflexive modernization is at the center of work of sociologists such as Anthony Giddens and Scott Lash, both of whom seek to develop multi-sited ethnographic understandings of the processes producing contemporary culture. These understandings are necessary. As Giddens argues, “expert systems are disembodying mechanisms because, in common with symbolic tokens, they remove social relations from the immediacies of context” (Giddens 28). It is this context that we seek to uncover through the making of maps.

Clarke’s method of situational analysis involves three cartographic approaches for mapping the situatedness and perspectives of all actors, human and non-human; discourses; and social worlds of/in complex phenomena. We created the three maps through a process documented in our video component, “Mapping the MCL Cancer Clinical Trial: Step-by-Step Instructions for Mapping Using Clarke’s (2005) Situational Analysis: Grounded Theory after the Postmodern Turn.” (See fig. 1.) In our first work session, we began the process of creating situational maps, which are designed to turn data into unordered and then ordered lists of the major human, nonhuman, discursive, historical, symbolic, cultural, and political elements of the research situation. Together, we went through all of John’s documents, writing down each actor or element on a single Post-it Note, then placing all of the post its on a whiteboard. After completing this process, we began to group Post-its around themes. A significant theme for us in the work session was the information literacy skills required for John as a patient to research and make a decision about which course of treatment to undertake. His own actions as an adept user of internet search engines, medical databases, and reader of complex information greatly informed his interactions with health and medical professionals. This analysis became the focus of a presentation that we gave at the Conference on Community Writing, held at University of Colorado at Boulder in October of 2017, in which we interrogated the notion of a deficit model of health literacy, in which certain patients are ill equipped to handle the complexity of the healthcare system, and argued that it is instead the system which must be held accountable for its opaqueness and system-centeredness. In essence, if one requires a Ph.D. and a well-connected network of insiders to find an appropriate clinical trial, something is terribly wrong with the system. The process of situational mapping helped us to make that argument, as the groupings of data points led to a pronounced emphasis on information literacy in the decision-making process. This presentation has led to activist futures for the project, as several audience members were community literacy scholars who are interested in partnering with us to collect more cancer patient decision-making narratives. This is exactly the goal of Clarke’s technique—to find where more data may be needed to find ever more avenues for research of a complex phenomenon. The map points to new maps to be made.

In our second maker session we created Clarke’s social worlds/social arenas map. This exercise is designed to lay out all of the collective actors, key nonhuman elements within the arenas of commitment in which they are engaged. We ask, what are shared ideologies, identities, and concerns of the actors and elements, and how might those be mapped in relationship to one another? As the video shows, we took up the same post-it notes from the earlier session and began to discuss the belief systems of those actors and elements involved, beginning with the patient. Over the course of an hour, we mapped and unmapped and remapped the various actors and elements, coming to grips with what John’s dataset revealed. By the end, you can see us drawing a slanted line that becomes, on one side, a shared set of commitments across patients, the local medical community, insurance companies and the media (see Fig. 3). On this side, patients are processed in a business model that rewards high volume radiation and chemotherapy treatments at local hospitals’ cancer centers. This represents an ecology of shared belief in the traditional standard of care for cancer treatment.

Figure 3. Final social worlds/social arena diagram from mapping session.

On the other side of the line is the experimental clinical trial ecology where clinical medical researchers, funders like the NIH, and Big Pharma reside. Their interests are aligned in moving experimental drugs to market, and a successful clinical trial is critical to their interests. These are very different business interests, and the patient often would not even know that the latter exists. There is no incentive, in most cases, for the patient to be brought over the line into the experimental. The social worlds map exposes the degree to which a patient must gather information that leads them to push themselves out, as John did, if they wish to participate in a cancer clinical trial.

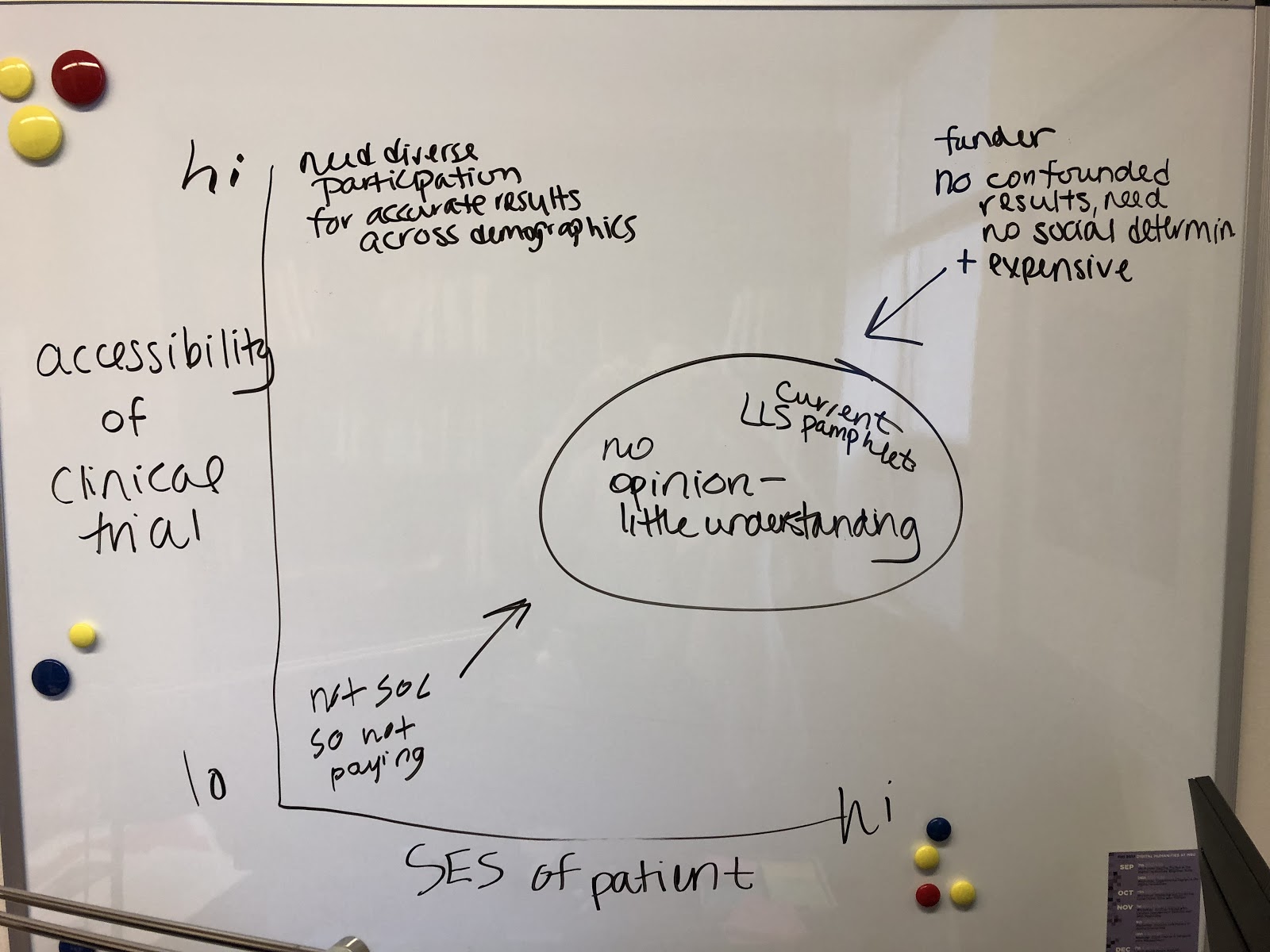

The final map in Clarke’s triad is the positional map, or a mapping of the major positions taken and not taken vis-à-vis axes of variation and difference, focus, and controversy. It is the positional mapping exercise that was easily our most difficult session. We took a failed try at creating the axes for the graph, first thinking through foci that appeared most important after the social worlds/arenas mapping exercise (attention to profit and autonomy of the patient in decision-making), but then realizing that it had moved us away from our focus on health equity activism. We then chose socioeconomic status and accessibility of the clinical trial to sharpen our attention on activist concerns and chose positional statement for the major actors from the social worlds/arenas map. Upon viewing them in relation to one another, an activist approach to the data set became clear (see Fig. 2).

Figure 4. The final arrangement in the positional map live session.

In the center of the graph is a circle with an island of those with little to no understanding (nor position taken) on the accessibility of cancer clinical trials. Inside of this circle is where patients and the local medical community are positioned. Around the edges are those with incentive to keep them there--the insurance companies (who do not want to fund an expensive, experimental clinical trial), and those stakeholders to the clinical trial itself (who do not want confounded results or the expense of adding participants from other socioeconomic and racial and ethnic groups). Finally, in the upper left-hand quadrant lies the activist position: that diverse participation in clinical trials is necessary for accurate results across demographics. This, then, becomes the launching point for further activist mapping.

Melding Different Mapmaking Approaches

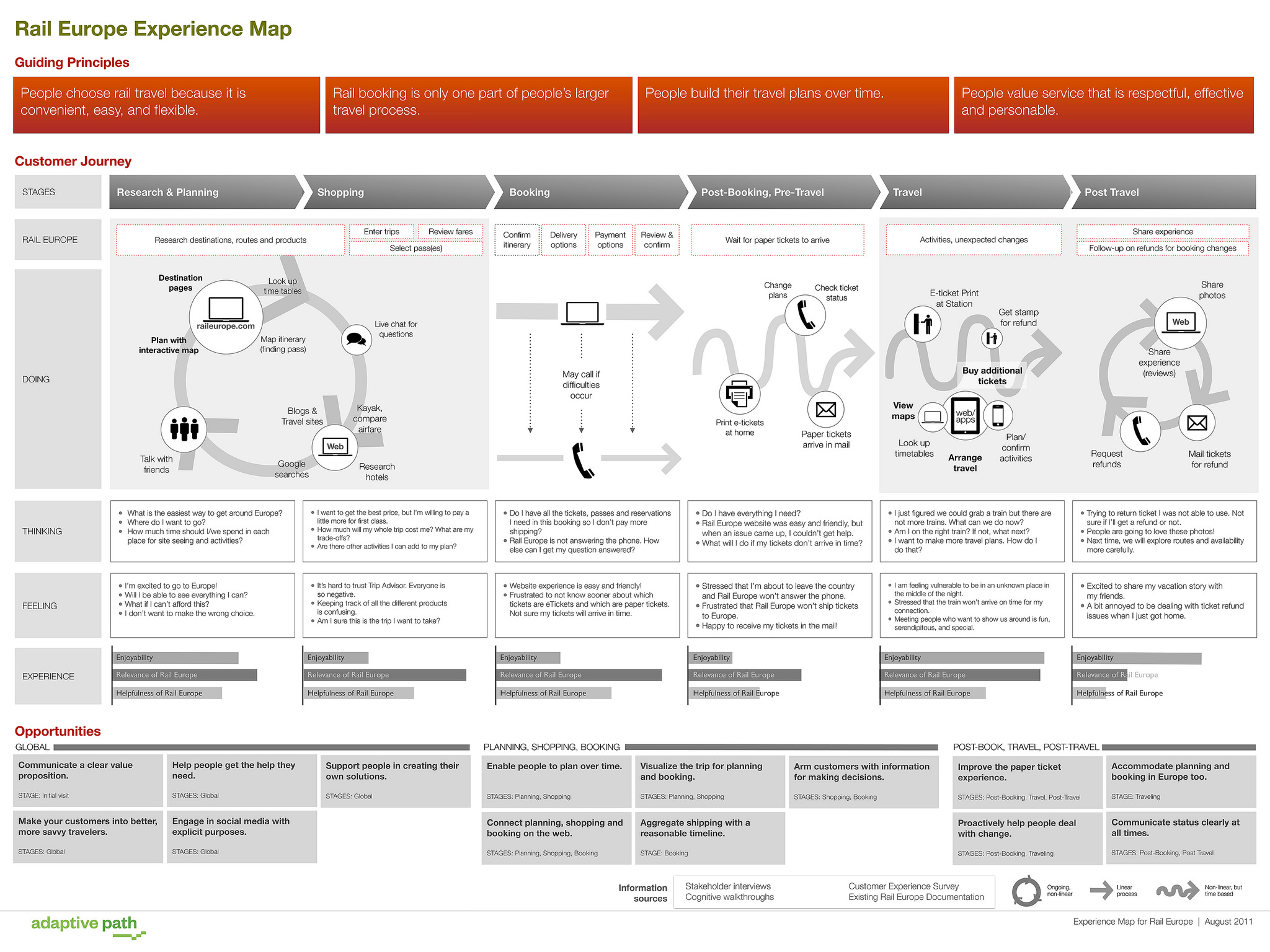

The Clarke method of mapping helped us to draw out the systems at work in the cancer clinical trial process, but in order to compare that to the individual’s point of view of the system, we decided to employ a mapmaking exercise of another sort. Experience (or journey) mapping is a popular method in user experience research and design, a process that leads to “an artifact that serves to illuminate the complete experience a person may have with a product or service” (Risdon). A journey map illustrates a person’s journey, and an experience map goes beyond to “engender a shared reference of the experience, a consensus of the good and the bad” (Risdon). In John’s journey mapping exercise (the WordPress site), he takes artifacts from his experience in the ibrutinib cancer clinical trial, from diagnosis through treatment, and maps them onto stages of touch points used in the user experience consultancy Adaptive Path’s experience mapping. Adaptive Path used these touch points (research and planning, shopping, booking, and travel) for the context of travel on Rail Europe.

Figure 5. Adaptive Path’s customer journey map (Polaine, Lovlie, and Reason).

John as patient “user” highlights a journey that is highly situated in complex information (seeking, translating, taking action), in the leveraging of relationships inside the clinical trial network. The journey also emphasizes his travel to the MD Anderson Cancer Center for the trial as well as the wealth and power of the MD Anderson Cancer Center and the cityscape created by it.

Our effort to integrate experience mapping and social worlds analysis is an experimental model to conceptualize a necessary foundation for intervention into a space that is largely obfuscated. Taken together, the map of the personal patient journey and the larger systems into which that patient journeyed offers insight to take action. It is here that we began our final mapmaking exercise—a necessary final step to create a health equity activist’s kit.

Our/Your Pathway toward Activism

The last map in our kit is a journey map for a health equity activist (see fig. 2). To make this map, we created a persona of a health equity activist, and a narrative for that persona, based upon the findings from our situational analysis. Personas are research-based, yet fictional, representations of users of a product or service, designed to “help you step out of yourself” and into the position of another (Dam and Siang). We hacked a downloadable journey map template designed by Kerry Bodine and Company (Figure 2) to create touch points based on activism in different venues and the difficulties that an activist might encounter in those places based upon John’s artifacts from his own journey. The outcome from the creation of the activist’s journey map is to identify potential avenues of exploration to intervene in the discourses and practices of those actors currently situated to prevent further equity in the cancer clinical trial enrollment process.

The multiple maps in our kit offer important counter-narratives to the resources currently available for patient cancer treatment and demonstrate how mapping the phenomena offers vantage points left unseen in critical arenas of public and private life. This juxtaposition of qualitative research methods, industry tools and practices (and the exercise of map making, testing, rejecting, iterating, and circulating) creates a powerful toolkit for activist scholarship and public engagement. We share our mapping kit with you for your own use in your own areas of concern. Additionally, we offer this worksheet of guiding questions as an additional aid to get started. We hope this toolkit offers a method for research and activism around complex problem spaces that can be difficult to navigate. Health equity is but one context for such a kit, albeit a critical one.

Braveman, Paula, and Sofia Gruskin. “Defining Equity in Health.” Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, vol. 57, no. 4, 2003, pp. 254-258.

Clarke, Adele. Situational Analysis: Grounded Theory after the Postmodern Turn. Sage, 2005.

Dallas, Mary Elizabeth. “Still Too Few Minority Participants in U.S. Clinical Trials, Study Finds.” HealthDay News, 21 Mar. 2014, www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=177384.

Dam, Rikke, and Teo Siang. “Personas—Why and How You Should Use Them.” Interaction Design Foundation, 13 Oct. 2017, www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/personas-why-and-how-you-should-use-them.

Giddens, Anthony. The Consequences of Modernity. Stanford UP, 1990.

Kanter, Rosabeth Moss. “Why Innovation is so Hard in Health Care—and How to Do it Anyway.” Harvard Business Review, 22 Feb. 2011, hbr.org/2011/02/why-innovation-is-so-hard-in-h.html.

Keefe, Patrick Radden. “The Family That Built an Empire of Pain.” The New Yorker, 30 Oct. 2017, www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/10/30/the-family-that-built-an-empire-of-pain.

Lawrence, T. E. Seven Pillars of Wisdom: A Triumph. Jonathan Cape, 1935.

Polaine, Andy, Lovlie, Lavrans, and Ben Reason. Service Design: From Insight to Implementation. Rosenfeld Media, 2013.

Risdon, Chris. “The Anatomy of an Experience Map.” Adaptive Path, 30 Nov. 2011, http://www.adaptivepath.org/ideas/the-anatomy-of-an-experience-map/