Christopher Justice, Loyola University Maryland

(Published November 18, 2019)

Anglers influence their physical environments in complex, often unintentional ways. They break branches, disturb shorelines, uproot vegetation, degrade rivers, kill fish, and frequently leave more than footprints: they leave trash along waterways such as food containers, bottles and cans, and fishing tackle detritus. As environmental historian Arthur F. McEvoy has written, “Any economic activity that uses water—which includes most of them—or that alters the character of the seabeds, tidal areas, or rivers in which fish live will have some impact on the ecology, hence on the productivity of a resource” (9). Recreational fishing is no different.

Even more problematically, the public places where recreational anglers fish, though technically monitored by state fisheries agents and other law enforcement officials, are largely unprotected given the immense areas they encompass. McEvoy argues that a major challenge in protecting fisheries is the elusiveness of culpability. Fisheries “provide a laboratory example of the problem of environment because . . . it is impossible to consign their husbandry to private owners” (McEvoy 14). We know waterways are degraded and fisheries are depleted, but assigning blame is profoundly difficult, especially given the “slow violence” fisheries experience. This “slow violence”—Rob Nixon’s term for the invisible and gradual destruction of nature that escapes the mass media’s penchant for sensationalized environmental catastrophes—is rampant because, after all, a massive oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico is, literally, more spectacular than a few soda cans lining a lake shoreline.

Nevertheless, while ethical anglers try to minimize their environmental impacts as much as possible, not every angler thinks or acts ethically. Environmentally, obvious benefits exist to the practice of ethical angling and, more specifically, cleaning up anglers’ discarded traces. However, equally important benefits also exist from a theoretical perspective. In a sense, these anglers’ detritus or material remnants function as material traces. More broadly, they can also—when archived, recomposed, and repurposed—function narratively and ecologically as shared totemic symbols of anglers’ fishing experiences that help narrate grander stories about fisheries.

Myra J. Hird reminds us how Earth itself is a regenerating world of waste “fueling the world’s organic and inorganic metabolism.” She points out how waste from one part of the planet—for example, oxygen released as waste from trees—is later consumed by animals. Furthermore, she helps us understand how waste ultimately depends on one’s point of view: one organism’s waste is another’s fuel. Or more bluntly, one person’s trash is another’s treasure. For Hird, waste is “conceptually vacuous” because everything and nothing can be considered waste. Or, as Susan Strasser writes, “what counts as trash depends on who’s counting” (3).

Like Hird, Strasser argues that “[n]othing is inherently trash” (5), and she suggests trash is largely contingent upon sorting and classifying, both of which have a “spatial dimension: this goes here, that goes there” (6). This relationship between trash and place is critical, for reimagining the trash within fisheries forces us to not only reconceptualize trash but places like fisheries, too. In this light, we should more fully reconfigure what a natural resource’s “product” and “waste” is. More specifically for this kit, what else do fisheries produce besides fish? When the answer to some is trash, how can we repurpose such trash into positive sources of rhetorical invention? This is what tackle caches seek to accomplish: they move beyond seeing fish as the primary product derived from a fishery and, instead, value the human discourse and narratives that fisheries and their trash can instigate.

Since fisheries are human constructs that are fundamentally abstract and complex, they demand explanations or stories to help materialize their essence and function. In this sense, they are what Timothy Morton calls a “hyperobject.” For Morton, hyperobjects are paradoxes that function as “strange strangers,” abstract yet material entities that defy our usual conceptions of time and space, occupy our imaginations and resources in sophisticated ways, and influence human behavior far more than humans have typically considered (6). However, because of these elusive qualities, hyperobjects are misunderstood, ignored, and underappreciated. Fisheries are hyperobjects, and tackle caches serve an important ecoliterate function in that they assist in watershed clean-ups, while they also seek to inspire strategies for inspiring narratives about fisheries.

The physicist Fritjof Capra has provided the best definition of ecoliteracy. He begins by stating that “understanding the principles of ecology requires a new way of seeing the world and of thinking—in terms of relationships, connectedness, and context” (20). He suggests these new ways of seeing and thinking require several perceptual shifts: “from the parts to the whole, from objects to relationships, from objective knowledge to contextual knowledge, from quantity to quality, from structure to process, and from contents to patterns” (20-21). Finally, he suggests that understanding the following concepts will help us better comprehend and identify those perceptual shifts: networks, nested systems (the networks within networks), interdependence, diversity, cycles, flows, development, and dynamic balance (23-29). In this sense, a tackle cache draws an eccentric relationship between garbage and storytelling; outlines specific things (items of garbage) and connects the negative effects of their presence to a much larger, complex whole known as a fishery; directs attention to the fishery’s quality; emphasizes a process that encourages anglers to clean up after themselves; and promotes the healthy development of fisheries.

Traditional notions of a “fish tale” are typically narrated by humans, often anglers, who tell stories of their wild adventures chasing fish. Melville’s Moby Dick, Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, and McLean’s A River Runs Through It immediately come to mind, but other “fish tales” exist, too. For example, news stories about beached whales, natural histories of keystone fish species such as menhaden or sharks, and documentaries such as Blue Planet all force us to reconceptualize our traditional notions of the fish tale, sometimes putting aside the angling elements of these tales, but still focusing narratively on the plights of different fish species. However, what they all still have in common is that each is told, ultimately, from a human perspective. Tackle caches help us move further into the posthuman because the narratives that emanate from these caches are instigated by nonhuman objects, and the unique relationships that objects in a cache share become primary agents for inspiring narratives.

According to the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary, a cache is “a hiding place especially for concealing and preserving provisions or implements; a secure place of storage; something hidden or stored in a cache; a computer memory with very short access time used for storage of frequently or recently used instructions or data.” In short, caches are like tackle-boxes. The phrase “tackle cache” plays upon the semantic flexibility of the word “cache,” which, like a tackle-box, serves as a storage place for an angler’s provisions, supplies, or random implements; and, like a computer cache, becomes a place where memories or instructions are stored.

My grandfather inspired this idea of a tackle cache, or more specifically, his cream-colored tackle box inspired it, which still resides in my basement. Whenever I wax nostalgic about him and my early years as an angler, I often open that box and a flood of memories instantly emerge. As two of the classical canons of rhetoric, invention and memory share a complicated history, and in this context, my grandfather’s tackle box and the memories it inspires for me were catalysts for the invention of a tackle cache.

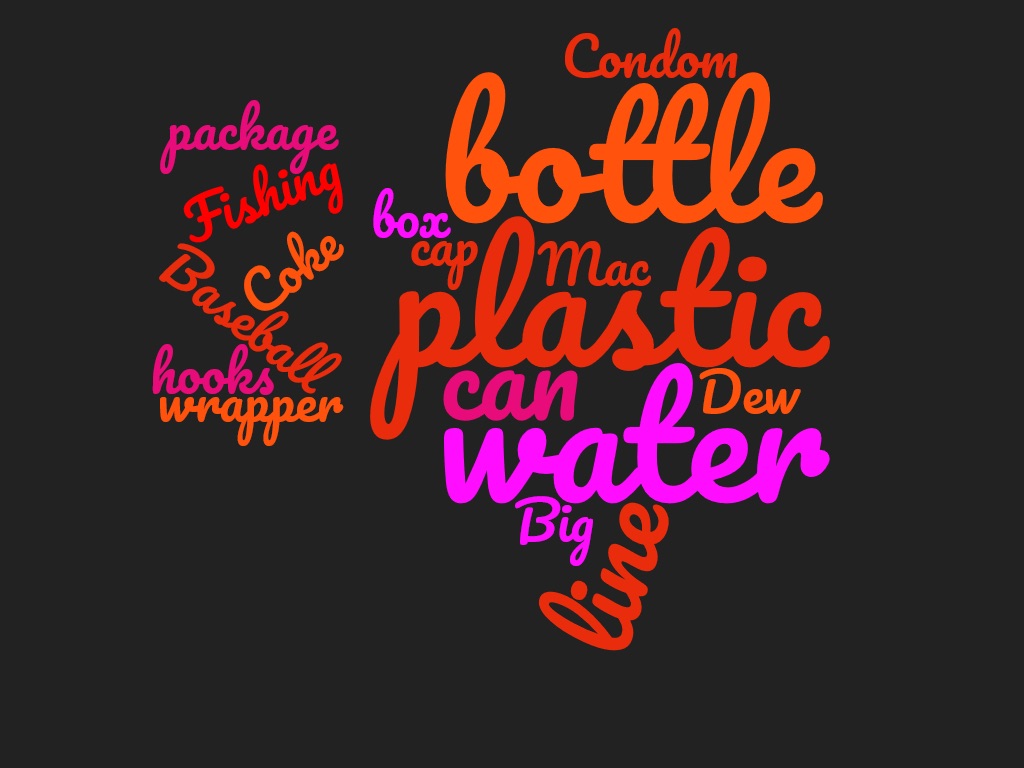

The tackle cache, then, is an object-oriented heuristic, or as Gregory L. Ulmer would call it, a heuretic for collective storytelling. A heuretic, for Ulmer, is a new type of invention strategy framed within “a new rhetoric . . . that does not argue but that replaces the logic governing argumentative writing with associational networks” (18). In essence, a tackle cache is a newly purchased or built-from-scratch tackle-box secured along a pathway beside a major body of water with brief instructions (these are optional) written to induce anglers to leave their traces in it. Once the tackle box is filled, its contents are then archived, recomposed, and repurposed to inspire “fish tales,” ideally about that local fishery. Once a tackle cache is filled, one can use the objects to generate computerized heuretics such as word clouds that inspire people to write narratives about that particular body of water and people’s interactions with it.

Figure 1. A tackle cache that has been filled with garbage along Liberty Reservoir in Eldersburg, Maryland.

Tackle caches are also inspired by fluxkits, which as Higgins writes are “small boxes of inexpensive materials assembled for personal use” made during the 1960s and 1970s by artists including George Maciunas, Ay-O, George Brecht, Dick Higgins, Alice Hutchins, and other Fluxists (34). Jentery Sayers posits that fluxkits are “textures of everyday life,” and in this case, they serve as textured assemblages of what was once a mysterious public’s interactions with a fishery. Sayers writes that Fluxkits “are sensory experiences, blurring distinctions between object and event, material and concept.” Echoing Higgins, this blur renders “physical or actual experiences central to the process of signification” (36). Tackle caches in this sense function as a book of objects that can be opened, perused, read, and closed like traditional print books. Similarly, tackle caches are also inspired by found object art (or Duchamp’s ready-mades); they tell a collective story inspired by angling detritus in which a fishery is the primary narrative agent. One can almost imagine a library of tackle caches.

Imagine an environmentally-inspired flaneur walking along the shoreline of a popular fishing hole with his or her tackle cache, but instead of leaving garbage behind, the flaneur finds inspiration by removing garbage. This flaneur uses garbage to inspire art because he or she then takes the cache and uses it to induce narratives, a unique act of what I am calling “detriphrasis,” which uses the concept of ekphrasis—or the rhetorical device where one uses descriptions of one type of art to inspire another type—to produce a unique type of garbage removal and object-oriented narratology. In short, this detriphrasis, with its environmentally-driven focus, is a type of ekphrasis that uses not art, but garbage to inspire art.

Examples of detriphrasis abound. One is in the popular art movement known as found art, where artists use found objects—often but not always excavated from trash heaps, dumpsters, or other locations for garbage or resuscitate objects that eventually will be trashed—stylistically in clever, aesthetic ways to produce unique art. Another is in the art movement known as “trashion,” which combines the words “trash” and “fashion” to evoke the idea of fashionable clothing made from trash.

Jane Bennett recalls in Vibrant Matter a similar experience when she stumbles upon trash along Cold Spring Lane in Baltimore, Maryland. She talks about the “provoked affects” this trash inspired in her, the “nameless awareness” and “impossible singularity” the trash caused (4-6). Garbage moves people with its uncanny agency, regardless of whether the material persuasiveness of trash repels us by its stench, reminds us of our entropic demise, instigates us to reflect on American capitalism and materialism, or lulls us into instantaneous environmentalism and pushes us to pick it up. Garbage and its ineffable thingness pushes us out of our mundane positions.

Ian Bogost uses the term “carpentry” to describe the “practice of constructing artifacts as a philosophical practice” (92), and in many ways, the creation of tackle caches fall under this description. More specifically, Bogost emphasizes a handiwork to this type of carpentry, and tackle caches, made by hand, are the result of, essentially, manual labor. As Bogost writes, “[T]hings fashion one another and the world at large” (93), and in these caches, the things themselves—the detritus of anglers—constitute the subsequent narratives.

An example of detriphrasis that I recently found in a tackle cache was a dirty “binky,” a baby pacifier that I discovered along a trail near Liberty Reservoir in Eldersburg, Maryland. One could in a writing class use this pacifier as a writing prompt that asks students to generate a narrative explaining how and why it appeared where it did; that asks students to write about the reservoir and its unique ecology from the pacifier’s point of view; or that asks students to tie the pacifier to other objects found in the cache and have them all appear in a narrative about a fish that resides in the reservoir. Additionally, in classes that emphasize ecology, students could trace the objects found in a tackle cache to their origins and write narratives about how those objects appeared alongside the reservoir. Numerous other possibilities exist.

Making a Tackle Cache

- Purchase a small tackle-box from any local sporting goods store OR design your own tackle-box.

- Find a local body of water—stream, river, pond, lake, bay, beach, etcetera—that is a popular location for fishing.

- Identify an obvious pathway that leads to fishing spots.

- Leave the cache along the pathway with instructions (optional).

- Return to the cache in a few weeks.

- Photograph its contents.

- Recycle or trash any pertinent items.

Figure 2. The closer the pathway is (in the above photo, the path is on the left) to the water, the better.

Options for Using a Tackle Cache

- Generate a “word cloud” from the contents.

- Use the photos to identify possible relationships among the items.

- Use those relationships to generate a narrative arc.

- Create a character who presumably used all the items.

- Recreate narratively the place where the items were found.

Figure 3. A word cloud generated from the items in a tackle cache placed along Liberty Reservoir in Eldersburg, Maryland.

Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Duke UP, 2010.

Bogost, Ian. Alien Phenomenology or What It’s Like to Be a Thing. U of Minnesota P, 2012.

“Cache.” Merriam-Webster.com,retrieved 3 Aug. 2017.

Capra, Fritjof. “Speaking Nature’s Language: Principles for Sustainability.” Ecological Literacy: Educating Our Children for a Sustainable World, edited by Michael K. Stone and Zenobia Barlow, Sierra Club Books, 2005.

Hemmingway, Ernest. The Old Man and the Sea. 1952. Reissue edition. Scribner, 1995.

Higgins, Hannah. Fluxus Experience. U.of California P, 2002.

Hird, Myra J. “The Phenomenon of Waste-World Making.” Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge, vol. 20, 2016.http://www.rhizomes.net/issue30/hird.html

Maclean, Norman. A River Runs Through It and Other Stories. 1976. U of Chicago P, 2001.

McEvoy, Arthur F. The Fisherman’s Problem: Ecology and Law in the California Fisheries, 1850-1980. Cambridge UP, 1986.

Melville, Herman. Moby-Dick.1851. 3rded., edited by Hershel Parker. Norton & Company. 2017.

Morton, Timothy. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World. U of Minnesota P, 2013.

Nixon, Rob. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Harvard UP, 2013.

Sayers, Jentery. “Kits for Cultural History.” Kits, Plans, Schematics, special issue of Hyperrhiz: New Media Cultures, edited by Helen J. Burgess and David M. Rieder, vol. 13, Fall 2015. http://hyperrhiz.io/hyperrhiz13/workshops-kits/early-wearables-essay.html

Strasser, Susan. Waste and Want: A Social History of Trash. Metropolitan Books, 1999.

Ulmer, Gregory L. Heuretics: The Logic of Invention. Johns Hopkins UP, 1994.

Volk, Tyler. "Gaia is Life in a Wasteland of By-products." Scientists Debate Gaia: The Next Century, edited by Stephen H. Schneider, James R. Miller, Eileen Crist, and Penelope Boston. MIT Press, 2004, pp. 27-36.