Megan Von Bergen, University of Tennessee, Knoxville

Bethany Mannon, Appalachian State University[1]

(Published November 10, 2020)

Evangelicals’ intransigence towards climate change is a paradox. As early as the 1970s, groups such as the National Association of Evangelicals committed to “solv[ing] critical environmental problems” (qtd. in Wilkinson 16). Some evangelicals subsequently maintained a limited commitment to environmental advocacy and employed religious terminology such as “creation care.” However, Barna Group and Pew Research Center polls find that climate change remains a low priority for evangelicals,[2] who are less likely than other practicing Christians or the general public to assert that “humans absolutely caused climate change” (“Are Humans Responsible?”). The pervasive “culture of scientific skepticism” among evangelicals poses one obstacle; a theology based in individual salvation rather than social engagement poses another (Wilkinson 95). Especially as climate impacts worsen, this gulf between evangelical and scientific communities calls for deft rhetoric that reconciles evangelical ways of being with substantive, sustained climate action.

Katharine Hayhoe, a climate scientist and an evangelical Christian, speaks into this exigence. An atmospheric scientist by training, Hayhoe directs the Texas Tech University Climate Center. Her faculty bio lists more than 125 published, peer-reviewed papers and her public rhetoric includes a TED talk, podcast interviews, and the Global Weirding YouTube series that answers common questions such as “What’s the Big Deal with a Few Degrees?” Hayhoe uses Twitter to amplify climate research and call her 147,000 followers to action.

Hayhoe is also a practicing Christian known for addressing fellow evangelicals, as in the Global Weirding video “The Bible Doesn’t Talk about Climate Change, Right?” Distilling the fraught history of the term “evangelical,” Hayhoe offers a simple definition: “people who take the Bible seriously” and see their Bible reading as a foundation for engaging the world. In that video she argues that Bible verses about God’s care for creation and Jesus’s teachings to act in “love for others, particularly those less fortunate than ourselves” motivate evangelical climate action. Even as she locates herself within this evangelical ethic of care, she distinguishes between Christians who are “religiously evangelical” and those who object to climate science because of their “politically evangelical” affiliation (“The Bible”). Although the growing influence of political evangelicalism interferes with Hayhoe’s rhetorical appeals, the distinction opens space for her to draw on shared religious landscapes in her climate advocacy.

In this paper, we explore the intersections between Katharine Hayhoe’s religious commitments and her climate rhetoric. We argue that Hayhoe cultivates an evangelical ethos and an invitational rhetoric that asks resistant publics to recognize climate action as belonging to the landscape of their faith. Situating our argument within rhetorical feminism, we first analyze how Hayhoe uses Twitter to publicly establish her ethos as a Christian climate scientist. We then examine how her invitational rhetoric in lectures at two Christian universities enacts that ethos, “renovating” both climate rhetoric and evangelical ways of being (Vander Lei). In this way, she offers a model for rhetorical work that addresses resistant publics from within their own discursive landscapes.

Ethos and Invitation as Feminist Rhetorical Practice

To frame our work on Hayhoe’s evangelical climate rhetoric, we draw on theories of rhetorical feminism, or dialogic, empathetic rhetorical practices sensitive to both rhetor and audience positionalities. We contend that rhetorical feminism extends beyond concerns with gender equity to a wide range of rhetorical practices, including Hayhoe’s advocacy for climate communication. Cheryl Glenn contrasts feminist rhetoric, which is centered on “advocat[ing for] . . . the equality of women and Others” (3), with rhetorical feminism, which is an expansive set of communicative practices that provide “ways to disidentify with hegemonic rhetoric” (4). Glenn elaborates on rhetorical feminism, writing:

Rhetorical feminism enacts goals that are dialogic and transactional rather than monologic and reactional and attends to (provisionally) marginalized audiences that may or may not have the power to address or resolve the exigence. Rhetorical feminism employs and respects vernaculars and experiences, recognizing them as sources of knowledge. And rhetorical feminism also shows us ways to reshape the rhetorical appeals, including a reshaped logos based on dialogue and understanding [and] a reshaped ethos rooted in experience. (4)

In other words, Glenn suggests that rhetorical feminism encompasses not only feminist content but feminist rhetorical practice. This work, regardless of its subject, eschews (masculine) hegemonic norms and instead relies on holistic ways of being human to forge persuasive connections. “Anchored in hope” (Glenn 4), such rhetoric “envision[s] alternative” ways of being and gives rise to meaningful action (Royster and Kirsch 145).

In this light, we frame Hayhoe’s climate communication among evangelical Christians, despite its lack of direct engagement with questions of gender, as rhetorical feminism.[3] Hayhoe’s communicative work is “architectonic” (Cordova 148), enabling her to “maneuver amid systems of power” (Hogg 398). (Re)making the landscape of her faith makes it possible for her to speak with, not at, her fellow believers who are skeptical of her scientific expertise because they locate authority in the Bible. We focus particularly on two concepts that emerge from Hayhoe’s discourse that are exemplary of rhetorical feminism: the value of an ecological, feminist ethos, and, rooted in that ethos, an invitational rhetoric that emphasizes relational, mutually respectful engagement as fostering change.

Especially online, ethos is often perceived as established through an author’s institutional reputation or credentials established in the “real world,” as Collin Brooke explains (184). Yet this model of ethos reduces it to something possessed by the rhetor, remaining intact across diverse rhetorical contexts, and does not account for how rhetoric is shaped by a rhetor’s standpoints: her values, relationships, and locations. Within feminist rhetorical theory, ethos is woven from the ecologies that a rhetor inhabits. Rather than something possessed by a rhetor, ethos is a “landscape of being with others” (Cordova 148). The horizons of this landscape shape a rhetor’s discourse and “render [it] persuasive” (Fleckenstein 328). Understanding ethos as ecological asks that a rhetor attend to her “standpoint,” or how the “places from which [she] speak[s]” enable her to reach particular audiences (Jarratt and Reynolds 52), in particular places, and at particular times. This holistic, ecological model of ethos describes how Katharine Hayhoe relates to potentially resistant evangelical publics: she speaks and writes not (only) as a climate scientist but as a Christian who draws on the horizons she shares with fellow believers to bridge the gulfs between faith and climate action.

The practice of invitational rhetoric both emerges from and reshapes a rhetor’s ethos. Invitational rhetoric, as Foss and Griffin write, offers an alternative to top-down models of rhetoric. “Rooted in equality, immanent value, and self-determination,” invitational rhetoric “invite[s] . . . the audience to enter the rhetor’s world and to see it as the rhetor does” (5). Scholars have built on Foss and Griffin’s work by considering how a rhetor’s “standpoint [or] horizon,” or the “range of vision that includes everything that can be seen from a particular vantage point” (Gadamer qtd. Ryan and Natalle 79), leads to mutual understanding. A view of invitational rhetoric that accounts for standpoint also aims at a “mutual enlargement of horizons” through dialogue (Crucius qtd. Ryan and Natalle 79). Such dialogue illuminates the places from which rhetoric emerges and “leads to a series of truths” that show the rhetor as belonging to the audience’s world and make transformation possible (Ryan and Natalle 85). Hayhoe’s expertise as a climate scientist, the moral weight of climate rhetoric, her personal faith, and Christian orthodoxy shape the horizons of her rhetoric in ways that transform her dialogue with her audience. Although “orthodoxy” is often “a restricting force” on religious rhetors, many draw on their faith to rewrite the boundaries of orthodoxy in fruitful ways, a process Elizabeth Vander Lei terms rhetorical renovation (xi). Renovating evangelical landscapes, Hayhoe’s rhetoric envisions alternative ways of being evangelical that welcome climate action and ground climate rhetoric in hope.

PART 1: HAYHOE’S PUBLIC EVANGELICAL ETHOS

Katharine Hayhoe cultivates a public ethos grounded in her identities as both a climate scientist and a committed Christian. This ethos, particularly visible through her use of Twitter. Hayhoe joined the platform in April 2009 and, as of January 2020, has published 41.6K tweets. Hayhoe maintains a robust scientific ethos on Twitter, starting with her bio (Fig. 1):

Fig. 1. Katharine Hayhoe’s Twitter Bio.

Using her title “professor” and setting her location to Texas Tech University, Hayhoe establishes herself as a climate researcher. Tagging TTUCSC (Texas Tech University Climate Science Center) creates a material link to an active research community. Finally, listing recognitions such as “UN Champion of the Earth” reinforces her reputation as a respected climate science scholar. Publicly, Hayhoe’s bio situates her within the landscape of climate discourse and reinforces that her standpoint is one of expertise.

Yet Hayhoe’s bio also identifies her as a pastor’s wife, a descriptor that roots her ethos in her faith. Her tweets continuously deploy evangelical discourse(s) to craft this ethos and invite viewers to recognize climate action as belonging to an evangelical landscape inscribed by a commitment to truth and concern for the needy. One tweet from January 2, 2020 (Fig. 2) circulates a talk Hayhoe delivered at The Meeting House, a Canadian church, and illustrates the fused evangelical and environmental ethe that define Hayhoe’s public rhetoric and invite Christian audiences towards action:

Fig. 2. Hayhoe tweet linking to a sermon about climate change she delivered at The Meeting House church.

Both the tweet and the embedded sermon locate Hayhoe’s climate advocacy within evangelical worlds. Her assertion that climate action is “faith expressing itself through love” invoke evangelical commonplaces about the importance of love and active, engaged faith. Echoing 1 Corinthians 13, a key New Testament passage naming faith and love the most important virtues, Hayhoe’s tweet paints the evangelical landscape as fertile ground for climate action and urges audiences to reimagine such action as demonstrating their love for God.

Users who click through from the tweet to the video (Fig. 3) see Hayhoe elaborate on the role of faith.

Fig. 3. Embedded sermon on climate change.

Importantly, she refers to her talk as a sermon. Engaging this familiar evangelical genre, the talk makes climate action visible to her audiences as part of their calling, particularly since it is delivered in a church, a space that “provide[s] affordances” for spiritual change (Sackey and DeVoss 199). Hayhoe testifies to her belief that Jesus provides “spiritual life” and expands that core tenet to find a parallel in the Earth providing physical life. She then turns to Scripture, another common move in sermons. Hayhoe quotes Genesis 1:28, the verse that gives humankind “dominion” over the Earth, and explains that the original Hebrew text (radah) means compassion. Using this, she urges her audiences to see how their sacred texts foster an interest in the well-being of Earth and its inhabitants. Framing her climate advocacy within familiar Christian discourses, Hayhoe shows how the natural features of her evangelical landscape nourish meaningful climate action.

Among the features of the evangelical landscape Hayhoe draws on to reach resistant evangelicals are a commitment to truth and a concern for the global poor.[4] As a scientist, Hayhoe assumes the importance of strong, accurate data. Hayhoe likewise inhabits a community staked on truth, as evangelical Christianity is known for its commitment to absolute, capital-T Truth. Hayhoe draws on this shared concern with truth as a point of contact in confronting evangelicals about the realities of climate change, as in the tweet below (Fig. 4):

Fig. 4. Hayhoe tweet asking JC, a climate denier, to value truth over politics.

Here, Hayhoe responds to a user (JC) who shares a political cartoon claiming President Obama paid scientists to fudge climate change data. Asking whether JC is “really a Christ-follower,” Hayhoe alludes to the fact that JC’s bio (omitted for privacy) names him as a Christian and suggests that if so, “truth is more important than politics.”[5] Hayhoe’s tweet (re)inscribes the boundaries of evangelical identity along a concern for truth, not politics, and appeals to that concern as inviting evangelicals like JC to read up on the abundant truths about the reality of climate change. (Helpfully, Hayhoe links to the video, so audiences may learn for themselves how some believers have misinterpreted passages, such as Genesis 9, to support climate denial rhetoric.) From this point of contact, the two worlds merge and grow, inviting readers to locate accepting scientific evidence for climate change within the landscape of a faith built around truth. Although many evangelicals will undoubtedly refuse such an argument, perhaps because Republican politics circumscribe their faith as we discuss later in the essay, Hayhoe’s interaction with JC makes space for evangelicals to reconsider their skepticism in light of their commitment to truth.

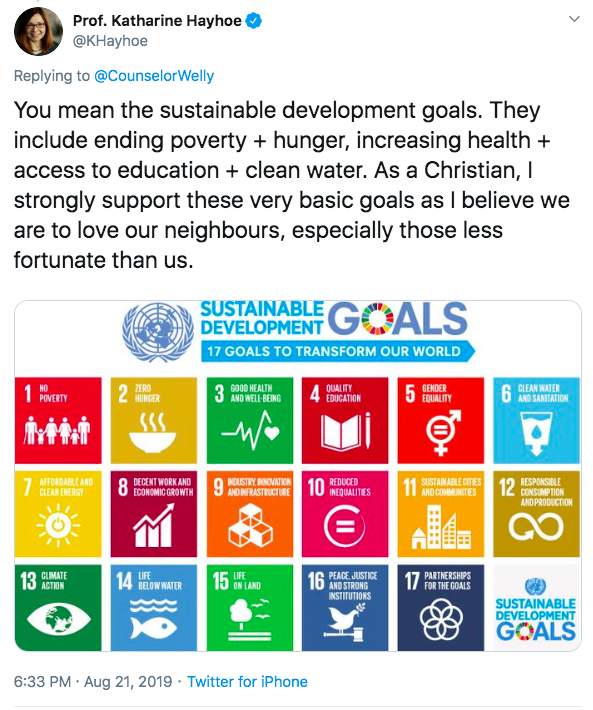

A second place where Hayhoe’s rhetoric invites her evangelical readership to see climate action as belonging to their religious horizons is a shared concern for the global poor. Bebbington’s widely cited definition of evangelicalism emphasizes the importance of actively spreading the faith, often by addressing material conditions of poverty around the world. Evangelicals, of course, have historically worked towards these ends in deeply colonialist ways; early missions to India, for instance, hinged on an imaginary Hinduism full of “violence and obscenity” and “reinforce[d missionaries’] sense of cultural difference and superiority” (Pennington 87). Centering her argument on motivating environmental action among fellow believers, Hayhoe's rhetoric does not encompass explicit "redress [of] the colonial effects" of missional traditions (Haas and Frost 171)—though recently, she has used her Twitter account to amplify Black climate scientists and scientists of color and call attention to the connections between climate change and racism. (See: “ . . . and @ayanaeliza (centre)”; “Climate change, pollution, coronavirus”). As a Christian climate activist, however, Hayhoe draws on commonplaces about evangelical concern for addressing poverty, (re)centering service and the humanity of the global poor, as in the tweet below (Fig. 5):

Fig. 5. Tweet with graphic listing UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Hayhoe testifies to an evangelical ethic of care rooted in love and suggests that such an ethic gives rise to practical acts of service, such as “ending poverty [and] hunger” and “increasing access to . . . clean water” (Fig. 5). Coupling this action to her audience’s Christian identity, she invites readers to make space for climate action within their traditions of service. This call is amplified as Hayhoe retweets messages that are not explicitly religious (Fig. 6):

Fig. 6. Hayhoe’s retweet of Peter Gleick, linking to BBC News article “India’s sixth largest city ‘runs out of water.’”

Climate scientist Peter Gleick calls attention to climate change as a global, humanitarian crisis; by retweeting his post, Hayhoe circulates the message among Christian ecologies. The tweet gains rhetorical force as it links secular science to evangelical activist landscapes, inviting devout publics to consider how their ethic of love calls them to climate action on behalf of the “eleven million people” affected by water shortages (Fig. 6). Drawing attention to the tragic realities of climate change for the global poor, Hayhoe urges her fellow Christians to expand their commitment to love and care to include caring about the material impacts of climate change.

Merging her evangelical and scientific ethe, Hayhoe crafts a public rhetorical identity in which she compellingly inhabits both worlds. As a scientist, she claims the expertise to speak convincingly on the reality and urgency of climate change. As a Christian, she draws on the landscapes she shares with fellow believers to extend an olive branch, inviting audiences to see how their faith sustains climate action. In instances where she addresses evangelicals specifically, Hayhoe draws on these twin identities to strengthen her ethos and chart a path forward for climate action motivated by faith.

PART II: “GOD’S SECOND GREATEST GIFT”

Katharine Hayhoe’s Twitter develops an evangelical ethos that opens space for her to meaningfully address evangelical audiences, including resistant publics. Her public advocacy with conservative religious groups—for instance, contributing to a publication by the National Association of Evangelicals, “When God and Science Meet”—suggests that the evangelical community recognizes her message as belonging to their world. Likewise, her popularity as a speaker at evangelical churches and colleges indicates that she has gained a foothold in that community. Indeed, given the way “location” interacts with “values [and] meanings” in rhetoric (Sackey and DeVoss 201), that Hayhoe’s climate messages are delivered within identifiably evangelical spaces gives them additional traction among faithful hearers. In two 2019 lectures at Taylor University and Oral Roberts University, which circulate on YouTube and on her website, Hayhoe deploys her ethos to address evangelical students characterized by competing commitments. Although the Barna Group reports that young evangelicals belong to a generation likelier than their older counterparts to say the Earth is warming because of human activity (“Are Humans Responsible?”), many students nevertheless inhabit a religious and political culture that perpetuates climate denial. Hayhoe’s invitational rhetorical strategies respond to this feature of their shared landscape and envision a socially-engaged, scientifically-literate evangelicalism.

Hayhoe’s college lectures exemplify an invitational rhetoric that makes room for her expertise and subjectivity. At Taylor University, she addresses a more narrowly Christian audience than in her public Twitter account and draws more fully on the resonance between climate action and Christian concern for global poverty. At Oral Roberts University, she extends her argument to address climate skepticism at greater length, calling on evangelicals’ commitment to truth. Both lectures integrate her evangelical standpoint and commitment to scientific inquiry, modeling an alternative to the fundamentalist rhetoric that often characterizes public evangelical discourses.

In her March 29, 2019, lecture at Taylor, Hayhoe teaches students to consider how their own standpoints within evangelical landscapes call them to engage climate science. Quoting a passage from Genesis that calls humans to stewardship, she proposes that the Earth is God’s “second-greatest gift” to mankind (second to Jesus Christ) (“Taylor University Chapel”). For this reason, Christians are obligated to attend to measurable, observable climate change worldwide. Hayhoe addresses this argument to Christian students who have witnessed poverty or feel called to mission work and urges them to locate environmental action as part of that calling. As the child of missionaries in Colombia, she too can testify to precarity of life for marginalized people “that may or may not have the power to address or resolve the exigence” of climate change (Glenn 4). Since evangelicals may accept her premise—the importance of caring for creation and the poor—but not the application to climate change, Hayhoe connects these dots. She constructs a narrative of climate changes that bring extreme, frequent, destructive weather, such as the 2018 monsoon season that flooded one-third of Bangladesh. “The risks are changing,” she explains. For evangelicals, this knowledge brings a particular obligation to act.

Hayhoe contends that “caring for every living thing on this planet, the responsibility that we’ve been given by God, is about caring for our brothers and our sisters, especially those who are already suffering.” She then argues that climate action or denial have implications for their Christian witness: “imagine going to someone [experiencing these risks] and handing them a Bible, and saying ‘be well, go in peace.’ That’s not who we are; that’s not what we’re designed to be.” Instead, evangelicals are called to action because of the “new hearts” they receive upon conversion. Hayhoe’s attention to climate change’s impact on the poor invites the listening students to expand their missional tradition to include meaningful environmental action.

Hayhoe’s Oral Roberts lecture extends this conversation to address problems with fossil fuel use in developing countries. Living abroad as a “missionary kid” showed her that communities without reliable power grids benefit more from developing local renewable energy sources than from acquiring fossil fuels. In a claim that demonstrates the challenges of employing tactics of rhetorical feminism to an audience that responds more to an anti-feminist ethos, Hayhoe frames this position as a pro-life stance. She explains that extractive industries “carr[y] a price tag that is paid by the people who live there,” such as the high instances of cancer near mountaintop removal in Appalachia and the health risks to fetuses and children after oil spills in the Niger delta (“Talking Climate Facts, Fictions and Faith at Oral Roberts University”). Oil and coal create the air, water, and soil pollution “responsible for one-sixth of all deaths around the world.” “If we truly are pro-life,” she argues, we “have to care about life from conception to death, not birth.” These claims invoke a social issue that evangelicals consider among the most pressing but ignore the anti-feminist implications and ideological foundations of pro-life movements that exacerbate issues (such as overpopulation) that deeply impact climate change. Hayhoe does include a pointed qualifier—“from conception to death, not birth”—to expand the meaning of “pro-life” and position students as already belonging to spaces that give urgency to climate action. However, her invitation “accords value and respect” to pro-life values and overlooks the violence and coercion of many pro-life movements (Foss and Griffin 17). We see Hayhoe’s strategy as potentially transformative for believers who hear her. However, this moment in the lecture—like her uptake of evangelical missional values—indicates that locating climate activism in the evangelical landscape prevents her from engaging the full implications of either feminist rhetoric or evangelical worldviews.

At Oral Roberts, Hayhoe’s invitational rhetoric underscores her ethos as a scientist, a move that counters those who dismissively “pat her on the head.” She names these myths directly:

When we talk about climate change, we hear a lot of “buts.” “But, isn’t it just a natural cycle?” or “Scientists haven’t studied this long enough to be sure.” “Those liberal atheist scientists are just making the whole thing up.” “Sea levels aren’t rising, they’re falling.” “It’s such a tiny amount of carbon dioxide, how could it affect something as big as our planet?” . . . Or, of course, between the months of November and April, my favorite: “It’s cold outside.” So, let’s look at these questions, because these are good questions—they make sense, right? (“Talking Climate Facts”)

Hayhoe’s summary treats skeptics as asking good-faith questions without treating denial as a legitimate intellectual stance or devaluing expertise, which scholars have raised as one critique of invitational rhetoric (Ryan and Natalle; Hammers and Alexander). Instead, she shifts the ground of climate debate toward open sharing of information. This frame, grounded on Hayhoe’s expertise, invites readers into conversation about the substantial evidence demonstrating climate change (Alexander and Hammers 7). Hayhoe explains the difference between climate and weather, asserting “we know that over climate time scales it is getting warmer.” To assess sea level changes “we have to look at the whole data record,” which shows that sea level is rising (“Talking Climate Facts”). She then explains natural cycles, the centuries-long history of climate research, and the errors in the 38 published studies questioning human influence on climate change. Addressing these objections, Hayhoe merges evangelicals’ commitments to, as Sharon Crowley puts it, “revelation, faith, and biblical interpretation” with a discourse of “empirically based reason and factual evidence” (Crowley 3). She invites listeners to see how a grounding in both can bring about civil discourse on a changing climate.

Hayhoe also pursues that renovation through the invitational rhetorical practices of humor and personal testimony, both responses to partisanship and skepticism. She elicits a ripple of laughter when she debunks a petition that falsely claims 30,000 signatures from scientists attesting that climate change “isn’t real”; the petition actually included signatures from non-scientists like the Spice Girls. She narrates her own faith journey, professing her conviction that 2 Timothy 1:7 calls Christians to act together in community. Witnessing “the evidence of God’s creation” like receding glaciers and thawing permafrost showed her that the planet is warming, and witnessing families living “close to the edge” worldwide spurs her climate action (“Talking Climate Facts”). By quoting “Christian-y objections,” she testifies to the need for a renovated evangelical climate discourse (“Talking Climate Facts”). Her own anecdotes tap into the currency that testimony holds in this culture. Evangelicals prize personal stories in part because of the culture’s historic emphasis on personal conversion and spreading the faith (Mannon 144). Most importantly for Hayhoe as an evangelical, locating knowledge in personal experience is a familiar way for believers to articulate religious convictions and to encourage others toward understanding and action.

PART III: LIMITATIONS

Despite her strong Christian ethos, Hayhoe faces two significant limitations: her gender and the increasing influence of politics on faith. As we discuss, Hayhoe’s gender marginalizes her—and other evangelical women who publicly exercise rhetorical agency—within evangelical communities. Most evangelical theologians and congregations prohibit women’s ordination; beyond preaching, the culture opposes women’s speech and leadership in explicit and implicit ways (Mannon 146). Hayhoe connects these patriarchal values to climate denial: she explains that her expertise has been dismissed because of her gender (“I’m often told”), and on Equal Pay Day in 2016 she tweeted, “The same people who call #EqualPayDay ‘feminist propaganda’ also pooh-pooh climate change. Coincidence? I think not” (“The same people”). She states unequivocally that greed, racism, sexism and hunger for power use “religious windowdressing to make itself more palatable,” one reason why evangelicals hold positions based on ideology rather than evidence or the Bible (“Inside the US”). Hayhoe navigates these constraints by invoking the faith that compels public rhetoric as in her Meeting House “sermon”; as she tells Taylor students, climate action is “the responsibility we’ve been given by God” (“Taylor University Chapel”) In this, she follows a tradition of feminist rhetors, such as nineteenth-century reformer Lucretia Mott, whose faith authorized them to speak (Glenn 15). As Hayhoe navigates the patriarchal culture of contemporary evangelicalism and deploys socially engaged theology in a new political context, she models how rhetors may repurpose community traditions to address resistant publics.

Unfortunately, another significant limitation on Hayhoe’s ability to renovate Christian ways of being is growing: the twin engines of her argument, evangelical ethos and invitational rhetoric, do little to mitigate the increasing alignment of evangelical communities with the Republican party. As historian John Fea notes, 81% of white American evangelicals voted for Trump in 2016 (Believe Me 5), and in one of her tweets Hayhoe blames the “toxic stew” of far-right politics for ongoing climate denial (“This is no surprise”). Fea shows that “fear is the political language conservative evangelicals know best,” and politicians reach evangelicals by promising to “protect them from the progressive social forces wreaking havoc on their Christian nation” (38-39). Speaking at Oral Roberts, Hayhoe attributes some resistance to US evangelicals’ fear of losing their affluent way of life if they are asked to replace fossil fuels. As right-wing political values and a rhetoric of fear reinforce the boundaries of an evangelical landscape, horizons shift in a way that makes some evangelical spaces, and the believers who dwell there, actively hostile to Hayhoe’s invitation.

Hayhoe’s rhetoric confronts this political evangelicalism and models alternatives. At Taylor, she paraphrases the Bible verse she finds most salient for climate activism, 2 Timothy 1:7: “God hasn’t given us a spirit of fear, therefore if we’re acting out of fear it’s not from God. God has given us power to act, a new heart to love, and a sound mind to make good decisions” (“Taylor University Chapel”). To address political evangelical pushback, she asserts that supporting climate action, including political actions, does not demand conversion to liberal politics or theology. She tells Taylor students that gaining new conviction “is not becoming something different.” Students do not need to surrender their biblical worldview or political identity to act on climate change, prospects that might alarm evangelicals who see themselves as countercultural voices righteously opposed to modern, secular society (Crowley; Fea).

The impact of Hayhoe’s work is hard to measure, yet there are indications that her rhetoric is finding some acceptance. Hayhoe’s advocacy bears fruit in organizations such as the Young Evangelicals for Climate Action, where she serves as a Senior Advisor. One empirical study also points towards the success of her lectures with evangelical audiences (Webb and Hayhoe). Conducted among students attending Houghton College, an evangelical institution in New York State, the study shows that Hayhoe’s presentations produce statistically “significant increases in proclimate beliefs” among her listeners (Webb and Hayhoe 277-78). Students who heard Hayhoe speak were, afterwards, more likely to acknowledge the harm of climate change and the importance of taking action. As a “culturally contextual communicator” (Webb and Hayhoe 280), Hayhoe draws on expansive feminist practices to motivate her public rhetoric and invite evangelicals to locate climate advocacy within the boundaries of their Bible-centered faith. By resisting political evangelicalism and gendered attacks on her expertise, she “put[s] hope in play, making a leap of faith beyond the evidence” to (re)make a barren landscape fertile for environmental advocacy (Glenn 46).

CONCLUSION

Hayhoe demonstrates that religious rhetoric can speak across the ideological divides that inhibit meaningful change. The invitational rhetoric we analyze in this essay locates climate action and evangelical belief as adjoining landscapes, connected through fused horizons of a commitment to truth and a care for the global poor. This work recasts climate change rhetoric in hopeful terms, countering the fear Hayhoe sees at the root of skepticism. As Cheryl Glenn reminds us, hope is not optimism; hope is better understood as actively working towards alternative ways of being. Hayhoe’s work holds out hope for evangelicals to reimagine their faith as motivating climate action, particularly among younger evangelicals who see themselves in a global coalition committed to justice and service.

This religious rhetoric holds significance for the field of rhetorical studies as it contends with fluid conceptions of fact and considers how to engage resistant publics amidst deteriorating public discourse. Hayhoe’s work demonstrates the value in an expanded understanding of invitational rhetoric that acknowledges the importance of a rhetor’s whole standpoint, including her expertise and religious (or other) commitments. Hayhoe’s knowledge of climate science research is core to her renovation of evangelical climate rhetoric, but such expertise gains persuasive power when she presents it as integrated with her faith. To shift dominant evangelical climate discourses, Hayhoe asks her audience to join her in a landscape that includes (sometimes in productive tension) both scientific literacy and Christian faith and values. Even if some listeners do not accept Hayhoe’s invitation, her work creates possibility, envisioning alternative, hopeful models of faith expansive enough to include climate change—models that may, eventually, take root. Hayhoe’s approach, inhabiting familiar landscapes of faith but widening their horizons, offers a model for other contexts where rhetors might successfully connect with resistant publics using invitational approaches that recognize the relevance of their standpoint and expertise.

[1] Authors’ note: Partisan divides between political and religious evangelicals were undeniably deep when we drafted this, mostly during Summer 2019. Still, the events of 2020 have made that divide deeper still. Prominent evangelical leader Al Mohler announced late this spring that, unlike in 2016, he would vote for Donald Trump, and as John Fea has documented at his blog, The Way of Improvement Leads Home, even conservative leaders such as John Piper have, as recently as October 2020, faced sharp pushback for their criticism of the current president. Hayhoe herself is Canadian, so her faith identity is not intertwined with American political commitments, yet as our article is released closer to the 2020 election than we anticipated, we acknowledge how the great difficulties of persuading political evangelicals, which we discuss in our limitations section, may seem insurmountable. Still, we also feel that amplifying Hayhoe's voice at this time is important. As neither Megan nor Bethany identifies as an evangelical, we have our points of disagreement with Hayhoe. Yet we see Hayhoe's rhetoric as a source of hope, which in contrast with the inflammatory rhetoric of political evangelicalism, models alternative ways of being faithful (see Royster and Kirsch 145) that extend to actively caring for the environment and for humanity.

[2] Historians commonly define “evangelicalism” as a Protestant movement centered on four axes: a commitment to 1) the Bible as the ultimate authority, 2) prioritizing spreading the faith through missionary and social reform efforts, 3) emphasizing Christ’s sacrificial death to redeem humanity, and 4) teaching that individuals need to be transformed through conversion. (Bebbington, Fea).

[3] Hayhoe does seem to identify as a feminist, as in this tweet expressing her frustration with “be[ing] metaphorically, and even once physically, patted on the head” while trying to advocate for climate change, and she publicly advocates for women scientists. However, because much of her explicit gender advocacy is for an audience of fellow scientists, rather than for the audience of evangelical Christians we discuss here, such advocacy is beyond the scope of this paper.

[4] Evangelicals, of course, have motivations other than their faith commitments. Hayhoe herself points in an interview to the influence of economic and political concerns on climate denial (Frykholm; Hayhoe, “The Bible Doesn’t Talk about Climate Change, Right?”). We briefly discuss Hayhoe’s response to political objections later in this essay, though our focus remains on the way Hayhoe draws on the Christian faith she shares with her audiences to invite them towards environmental action.

[5] Tweets are public data and do not require IRB review. Nevertheless, JC’s account is much smaller than Hayhoe’s and unlike the other public-facing, professional accounts cited here, JC uses Twitter as a private citizen for a range of purposes unrelated to climate science. In that light, to maintain his privacy, we chose not to engage with his tweets and we have anonymized his Twitter handle in the image above.

Alexander, Brian Keith, and Michelle Hammers. “An Invitation to Rhetoric: A Generative Dialogue on Performance, Possibility, and Feminist Potentialities in Invitational Rhetoric.” Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, vol. 19, no.1, 2019, pp. 5-14.

Barna Group. “Are Humans Responsible for Global Warming?” Barna.com, 22 Sept., 2016, www.barna.com/research/humans-responsible-global-warming.

Bebbington, David W. Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s. Unwin Hyman, 1989.

Brooke, Collin Gifford. Lingua Fracta: Towards a Rhetoric of New Media. Hampton Press Inc., 2009.

Cordova, Nathaniel I. “Invention, Ethos, and New Media in the Rhetoric Classroom: The Storyboard as Exemplary Genre.” Multimodal Literacies and Emerging Genres, edited by Tracey Bowen and Carl Whithaus, U of Pittsburgh P, 2012, pp. 143-163.

Crowley, Sharon. Towards a Civil Discourse: Rhetoric and Fundamentalism. U of Pittsburgh P, 2006.

Fea, John. Believe Me: The Evangelical Road to Donald Trump. Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2018.

Fleckenstein, Kristie S. "Cybernetics, Ethos, and Ethics: The Plight of the Bread-and-Butter-Fly.” JAC, vol. 25, no. 2, 2005, pp. 323-346.

Foss, Sonja K. and Cindy Griffin. “Beyond Persuasion: A Proposal for an Invitational Rhetoric.” Communication Monographs, vol. 62, 1995, pp. 2-18.

Frykholm, Amy. “A Climate Scientist Talks—Respectfully—to Climate-Change Skeptics.” Christian Century, 26 Feb. 2018, www.christiancentury.org/article/interview/climate-scientist-talks-respectfully-climate-change-skeptics. Accessed 1 May 2020.

Glenn, Cheryl. Rhetorical Feminism and this Thing Called Hope. SIU Press, 2018.

Haas, Angela M. and Erin A. Frost. “Toward an Apparent Decolonial Feminist Rhetoric of Risk,” Topic-Driven Environmental Rhetoric, edited by Derek Ross, Routledge, 2017, pp. 168-186.

Hayhoe, Katharine. “What’s the Big Deal with a Few Degrees?” YouTube, uploaded by Global Weirding with Katharine Hayhoe, 20 March 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6cRCbgTA_78.

---. “The Bible Doesn’t Talk About Climate Change, Right?” YouTube, uploaded by Global Weirding with Katharine Hayhoe, 4 Jan. 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=SpjL_otLq6Y&feature=youtu.be.

@KHayhoe (Katharine Hayhoe). Bio. Twitter, twitter.com/KHayhoe.

---. “and @ayanaeliza (centre) and the man I’ve looked up to since I was a student, pioneering @NCAR climate modeler Warren Washington (right)” Twitter, 15 June 2020, 12:06 p.m., https://twitter.com/KHayhoe/status/1272561051859652608.

---. “Climate change, pollution, coronavirus...what do they have in common? All disproportionately affect the marginalized, the vulnerable, the poor; those already suffering, already disadvantaged, already oppressed; exacerbating injustice, racism, and poverty.” Twitter, 1 June 2020, 1:47 p.m., https://twitter.com/KHayhoe/status/1267513179871088640.

---. “Hi JC - if you’re really a Christ-follower and truth is more important to you than politics, then please have the courtesy to update your understanding here: m.youtube.com/watch?v=Iq8Jo9QN0qA … and then.” Twitter, 5 Feb. 2019, 4:40 p.m., twitter.com/KHayhoe/status/1092946029740204032.

---. “I’m often told I am “pretty” but I have no idea what I’m talking about. I’ve been metaphorically, and even once physically, patted on the head hundreds of times. The question is not why are we feminist. The question is: why are so many so sexist. That’s what needs to be fixed.” Twitter, 5 April 2019, https://twitter.com/khayhoe/status/1114319448645574656

---. “Inside the US, it’s due to decades of greed, racism, sexism and hunger for power using religious windowdressing to make itself more palatable and further its aims. . . .” Twitter, 4 Aug. 2019, 2:10 p.m., twitter.com/KHayhoe/status/1158077698603913216.

---. “My Sunday sermon began what we believe + why it matters. I connected the dots to climate change, and ended by sharing hopeful, practical steps to action ... because the only thing that matters is when our faith expresses itself through love.. . . . ” Twitter, 2 Jan. 2020, 8:33 p.m., twitter.com/KHayhoe/status/1212909786502717440.

---. “This is no surprise. It is rare for me to be attacked on social media by someone from the US who doesn’t have MAGA in their profile, a Cdn who doesn’t hate the PM and immigrants, a Brit who’s not pro-Brexit....climate denial’s just one ingredient of the same toxic stew.” Twitter, 14 June 2019, 9.22 a.m., twitter.com/KHayhoe/status/1139568731934380032.

---. “You mean the sustainable development goals. They include ending poverty + hunger, increasing health + access to education + clean water. As a Christian, I strongly support these very basic goals as I believe we are to love our neighbours, especially those less fortunate than us.” Twitter, 21 Aug. 2019, 3:33 p.m., twitter.com/KHayhoe/status/1164304546686013440.

Jarratt, Susan C. and Nedra Reynolds. “The Splitting Image: Contemporary Feminisms and the Ethics of Ethos.” Ethos: New Essays in Rhetorical and Critical Theory, edited by James S. Baumlin and Tita French Baumlin, Southern Methodist UP, 1994, pp. 37-64.

Mannon, Bethany. “Xvangelical: The Rhetorical Work of Personal Narratives in Contemporary Religious Discourse.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 49, no. 2, 2019, pp. 142-162.

Noll, Mark A., et al. When God and Science Meet: Surprising Discoveries of Agreement. National Association of Evangelicals, 2015.

Pennington, Brian K. The Other Without and the Other Within. Oxford UP, 2005.

@PeterGleik (Peter Gleik). “Sorry for yelling, but nearly ELEVEN MILLION PEOPLE LIVE IN CHENNAI. The southern Indian city of Chennai (formerly Madras) is in crisis after its four main #water reservoirs ran completely dry.” #water #watercrisis BBC News - Chennai water crisis.” Twitter, 18 June 2019, 11:59 a.m, twitter.com/PeterGleick/status/1141057911981924352.

Royster, Jacqueline Jones, and Gesa E. Kirsch. Feminist Rhetorical Practices: New Horizons for Rhetoric, Composition, and Literacy Studies. SIU Press, 2012.

Ryan, Kathleen J., and Elizabeth J. Nathalle. “Fusing Horizons: Standpoint Hermeneutics and Invitational Rhetoric.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 31, no. 2, 2001, pp. 69-90.

Sackey, Donnie Johnson and Danielle Nicole DeVoss. “Ecology, Ecologies, and Institutions.” Ecology, Writing Theory, and New Media: Writing Ecology, edited by Sidney I. Dobrin, Taylor & Francis Group, 2011. pp. 195-211.

“Talking Climate Facts, Fictions and Faith at Oral Roberts University.” Lecture by Katharine Hayhoe, katharinehayhoe.com, 17 Apr. 2019, katharinehayhoe.com/wp2016/2019/04/17/talking-climate-facts-fictions-and-faith-at-oral-roberts-university.

“Taylor University Chapel - 03-29-19 - Katharine Hayhoe.” Taylor University, YouTube.com, 3 Apr. 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=XvYvDeRbfc8.

Vander Lei, Elizabeth. “Introduction.” Renovating Rhetoric in Christian Tradition, edited by Elizabeth Vander Lei, et al., U of Pittsburgh P, 2014. pp. ix-xvi.

Webb, Brian S. and Doug Hayhoe. “Assessing the Influence of an Educational Presentation on Climate Change Beliefs at an Evangelical Christian College.” Journal of Geoscience Education, vol. 65, 2017, pp. 272-282.

Wilkinson, Katharine. Between God and Green: How Evangelicals are Cultivating a Middle Ground on Climate Change. Oxford UP, 2012.