Derek M. Sparby, Illinois State University

(Published March 24, 2022)

1. A (Very) Brief Introduction to Political Memes

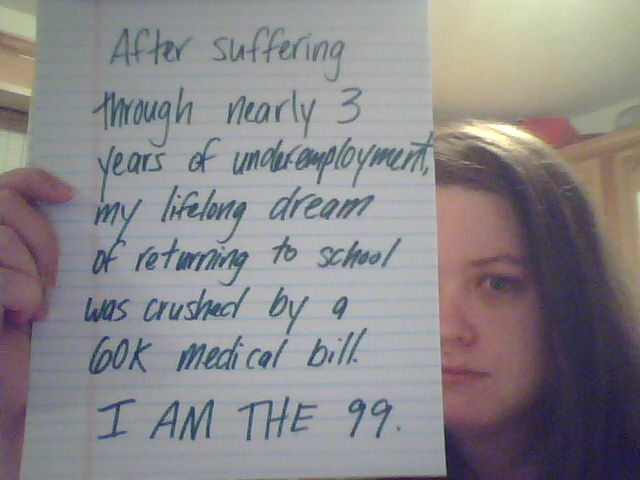

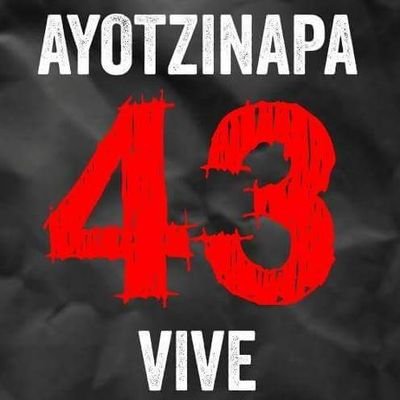

At this point, we clearly cannot ignore memes and their capacity to circulate, reflect, and create cultural meaning. These simple, mundane texts have the power to make us laugh, cry, think, and sometimes even act, and they influence the way we think about political issues. Julia R. DeCook shows how memes are propagandistic, arguing that they “serve as a vehicle to express either an individual or a collective voice. They are a reflection of the cultural spaces from which they emerge” (486). Ben Weatherbee argues that memes can act as rhetorical topoi that compel us to reexamine the moving parts of the rhetorical situation,” and shows how the “binders full of women” memes impacted the 2012 election. Heidi E. Huntington presents the Pepper Spray Copy meme as an example of powerful visual political rhetoric. Bradley E. Wiggins examines political memes as discursive ideological tools. Stephanie Vie has shown how something as simple as changing a Facebook profile image to display the Human Rights Campaign (HRC) logo can show LGBTQ+ solidarity (Figure 1), Ryan Milner (“Pop Polyvocality”) has shown that those who could not participate in the Occupy Wall Street (OWS) movement in person created “I am the X%” memes to demonstrate their solidarity with—or opposition to—it (Figure 2), and An Xiao Mina has demonstrated how memes are integral to activist movements, such as #UmbrellaMovement in Hong Kong (Figure 3), #BlackLivesMatter in the US (Figure 4), and #Ayotzinapa in Mexico (Figure 5).

Figure 1: Human Rights Campaign Logo

Figure 2: Occupy Wall Street Meme

Figure 3: #UmbrellaMovement Meme

Figure 4: #BlackLivesMatter Meme

Figure 5: Ayotzinapa 43 Meme

The power of memes comes from their ability to convey a lot of information quickly. For instance, take the HRC logo (Figure 1). Its message is totally visual; many people recognize the equal sign as both an argument for marriage equality and as the HRC logo. Conversely, the OWS meme (Figure 2) contains quite a bit of text, but ultimately boils a complex issue—wealth inequality—down to a one-sentence anecdote that, coupled with the image of the storyteller, shows how it affects everyday people. Taken together as a meme series, all the OWS memes show the sheer volume of people whose lives have been negatively impacted by wealth inequality. The Umbrella Movement became a meme after protesters in Hong Kong began using umbrellas as a form of passive resistance to Hong Kong police. Memers “remixed [a photo of Xi Jinping] to show him holding a yellow umbrella” (Mina 88), and then images of yellow umbrellas became symbols of protest (Figure 3). The repeating text in the Black Lives Matter meme (Figure 4) is a reference to the fact that police keep killing unarmed and innocent Black people. The text becomes a mantra, a repeated reminder of the value of Black lives. The Ayotzinapa 43 meme (Figure 5) refers to Mexican students who were abducted and are now missing, believed to have been disappeared by local law enforcement. Memes surrounding #Ayotzinapa demand that the Mexican government take accountability and reform. The “vive” (Spanish for “live”) in this iteration references hope that the 43 men will be found alive. All five of these memes seem so simple, but to someone tuned into the visual and political cues, they carry deeper meanings and implicit calls to action, all in a glance.

Memes about U.S. politics are always circulating in social media, but they see an obvious uptick during election seasons. These memes are often in support of or opposition to political candidates, parties, or movements, and many have become polarizing sources of mis/disinformation. As a rhetorical meme scholar and casual memer, I’m interested in how memes are used as vehicles for political disruption. As a queer feminist, I’m interested in how intersecting identities and unequal power relations result in women and women of color being disproportionately affected by memetic representation. As an activist and teacher, I’m interested in how we can make meaningful interventions into political memetic creation. This article pulls these threads together, examining political memes to reveal how some function demagogically by spreading mis/disinformation while insulating and further dividing political parties. Importantly, I do not argue that these memes are pure demagoguery, per Patricia Roberts-Miller’s definition, but that they are demagogic texts that function as part of larger cultural discourses and ideologies in U.S. politics that pit progressives and conservatives against each other through binaries that seem unreconcilable.

To find the memes I analyze below, I visited digital spaces with heavy political meme circulation, including subreddits on Reddit, groups on Facebook, profiles on Twitter, and threads on 4chan between 2015 and 2018. I strove to find a balance between progressive and conservative groups and saved around 200 memes that followed specific patterns of demagogic mis/disinformation, which I highlight below. I also took notes on snippets of conversations surrounding the memes’ circulation so that I could understand the context in which they were shared. I am intentionally not naming specific communities or profiles for two reasons. First is their right to privacy. Often these communities circulate text and images under the presumption that content will stay within the group. Obviously, this level of privacy can never be a guarantee on the internet, but I strive to protect it when I can. Second, I do not want some of these communities of harm to know that I am a frequent visitor. I received some negative attention from one community after I published an article about them, and so I am making a conscious decision to protect myself.

From my collection of 200 political memes, I examine memes circulated in largely conservative spaces depicting Hillary Clinton and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to not only demonstrate how political women are treated in memes, but also to show how factors such as visibility, age, and race result in distinct misogynistic memetic treatment. I define misogyny here as negative treatment of women that reinforces gender role normativity. To balance this representation of the memetic party divide, I will also present memes circulated in predominantly progressive spaces that represent Kim Davis and Kellyanne Conway. Finally, I corroborated my meme collection with an image search of publicly available political memes representing women.

I chose memetic representations of these four women deliberately. Clinton was an obvious choice because she was so visible during the 2016 election, although I also could have selected Elizabeth Warren or Kamala Harris since they were both highly visible in the 2020 election. I selected Ocasio-Cortez because her quick rise to fame as one of the young leaders of the Democratic Party, coupled with her identity as a young Latina woman, has made her one of the most frequently memed political women. I chose Davis—the former Rowan County clerk in Kentucky—because she gained national attention in 2015 when she refused to issue same-sex marriage certificates, and Conway because she was highly visible during the 2016 election. And, quite frankly, it was difficult to find progressive leaning memes about conservative women politicians, especially conservative women of color. I also wanted to compare how each side of the spectrum memes the intersection of politics, race, and gender, but—perhaps unsurprisingly although still disappointingly—there haven’t been many highly visible woman politicians of color in the GOP. Memes about conservative women of color exist, but I could not find a large enough dataset to be able to extrapolate general claims. I want to be careful here to note that I am not saying that progressive memers make fewer demeaning memes; in fact, I show below that the memes I did find use the same tactics as the conservative ones. It’s also important to note that, while I spend a lot of time in meme spaces, I cannot be everywhere on the internet at once, so it’s possible that readers are aware of memes that would suit this study that I do not address.

2. Memes, Identity, and Politics

Before I begin, it’s useful to provide a working definition of memes because they can take many forms. When Richard Dawkins coined the term in 1976—long before the social web in its current form existed—he defined it as cultural information spread from person to person (like genes, but with culture)[1] . With the rise of digital technologies, we’ve moved well beyond this analogic definition, but the core—the transmission of cultural information—remains intact (Shifman). Consider the 2016 election, for instance. Countless analog and digital memetic artifacts circulated, including MAGA hats, phrases like “basket of deplorables” and “nasty woman,” gifs of Trump tackling news logos, Vines of Hillary chilling in Cedar Rapids—all of these shifted and changed as they were circulated in analog and digital spaces. For instance, the phrase “make America great again” has been remixed in several ways, such as “make racists scared again” and “make America white again.” Some core part of the original message remains intact as a clear referent to the original version—in this case “make” and “again” as well as references, general and specific, to American culture. In this way, memes are iterative.

This study examines political image macro memes, which depict a recognizable figure and include text that can range from sharp critique or untruths to high praise or support. Generally, image macro memes are ironic in their depictions and often represent their views through sarcasm and biting humor. However, as I will show below, the subtlety of irony tends to be lost in political memes that can often be taken at face value. Image macro memes are often light trolling at their most innocuous and downright inflammatory at their most dangerous. I use “innocuous” and “dangerous” here intentionally. Several meme scholars have pointed to the ways in which memes are created for “the lulz,” or laugher had at another’s expense (Milner, “Hacking the Social”; Phillips; Woods and Hahner). A key aspect of what Milner calls the “logic of lulz” is that it “often antagonizes the core identity categories of race and gender, essentialising marginalized others” (“Hacking the Social,” 64). Moreover, Heather Suzanne Woods and Leslie A. Hahner point to the ways that ironic memes use “for the lulz” to dodge responsibility. They speak specifically to alt-right memes and racism, but as the analysis below will show, the same can be said both of some progressive memes and of sexism and misogyny: “the use of lulz often participates in the disavowal of one’s racist actions. Such disavowal recognizes the racism contained in far-right memes but refuses to accept responsibility for conveying racism” (105). They add that “what was once extreme—racism, misogyny, anti-Semitism, anti-queer, etc—becomes emboldened by the power of memes” (122). Recognizing this function of political memes is important because they have the power to shape digital discourses around gender, race, ethnicity, and other identity markers. As Woods and Hahner put it, backed by Milner’s (“Hacking the Social”) research on memes and Poe’s Law,[2] “ironic hatred is still hatred” (129). As such, memes and their ironic representations often preclude possibilities for productive discourse, which can be dangerous to democracy.

It’s no secret that women and people of color are often subject to memetic representation that reinforces inaccurate sexist and racist stereotypes that uphold systemic injustices. As I demonstrated in my dissertation, women are often depicted as objects of male fantasy, as undesirable, or as lacking intelligence (Sparby, Memes and 4chan and Haters, Oh My!). Something that these memes have in common is that they serve as indicators of what a heteronormative “good” woman is in a patriarchal society. Through memetic representation, women are told how it is acceptable to behave. Roberts-Miller emphasizes that this is inherently demagogic, explaining that “demagoguery is generally closely connected to specific constructions of masculinity…. It often appeals to rigid notions of gender” (Rhetoric, 177). This becomes the overarching message behind most negative memes depicting Hillary Clinton, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Kim Davis, and Kellyanne Conway: not only are none of them “good” women, but they are also unfit for political office by virtue of being women. In addition, memes depicting people of color also often reinforce stereotypes about what a “good” Black person, a “good” Mexican, or a “good” Muslim is by comparing them to “good” white people and creating a binary between those who conform to hegemonic whiteness and those who do not (Milner, “Hacking the Social”; Sparby, Memes and 4chan and Haters, Oh My!). I will demonstrate the subtleties of each’s representations below, but one overarching theme for all three is appearance. Clinton and Davis are too ugly, Ocasio-Cortez is too pretty, and Conway is somehow both. In all cases, their appearance overrules any of their qualifications. As a young Latina, Ocasio-Cortez’s memetic treatment is even more insidious, hinging on the intersections of her race and age with her gender.

One of the main conversations that emerged during the 2016 election was the question of “likeability” and whether or not a woman candidate can be likeable enough to be president, instead of focusing on their capability to do the job, which Weatherbee warned us about in 2015: “when voters assess an election based on which candidate has won the ‘meme war,’ some ability to rationally deliberate based on two candidates’ many arguments goes by the wayside.” Even now as I write this in late 2019, the same conversations are happening about Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris as potential Democratic nominees. Memes are part of this discourse. They feed into it through unfair and misogynistic representations of women candidates, perpetuating harmful stereotypes and forming political opinions.

I say “forming” political opinions, but this is not quite the correct term. We live in filter bubbles (Pariser) and social media echo chambers that are genuinely difficult to break out of if we want to encounter perspectives other than our own mirrored back at us.[3] As the Wall Street Journal’s “Blue Feed, Red Feed” graphic shows, memes circulate within these bubbles and rarely pass through these filters. As such, they often do not “form” our opinions so much as they reflect and amplify them. This means that memes like the ones below are genuinely dangerous because they are so insular and polarizing—they not only actively spread mis/disinformation, but they revel in doing so. Through viewing these memes as an “insider,” or as someone who already supports their message, the viewer is less likely to consider differing opinions or, in some cases, even facts. The more often the viewer sees these kinds of memes, the less likely they are to be open to democratic discourse or civil debate. Therein lies a major problem: How can we have civil dialogue across party lines if the memes we encounter daily only reinforce the beliefs we already have? The following sections analyze Clinton, Ocasio-Cortez, Davis, and Conway memes according to their focus on appearance, distracting or irrelevant information, and conspiracy theories or outright lies.

2.1. Appearance

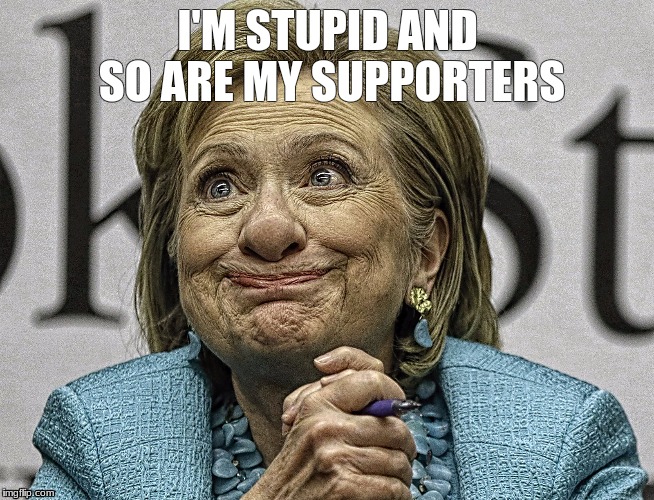

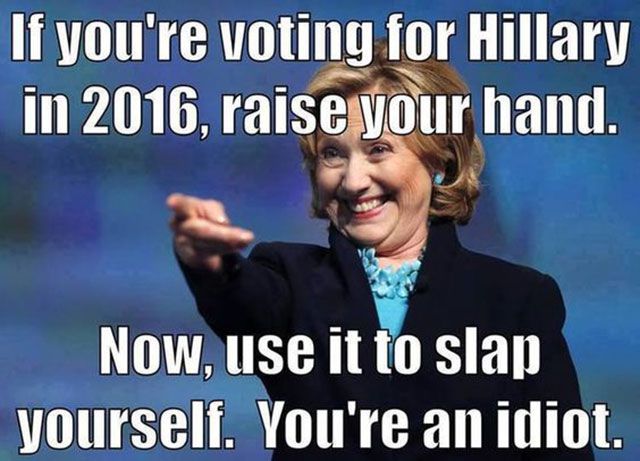

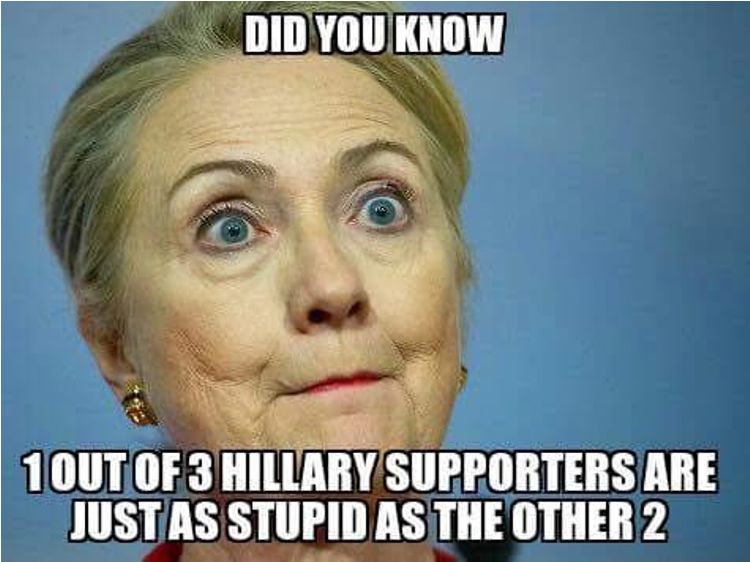

First, appearance. Clinton is an animated woman of many facial expressions, and memers often choose photos of her at awkward moments. Figure 6 is clearly photoshopped to make her look older, deepening the lines on her face, increasing the size of her nose, and all around making her look almost like she is not quite human. The other two do not appear to be photoshopped, but they have also caught her at odd moments. Figure 7 and images like it are often used to highlight that Clinton is evil; although she appears to be smiling excitedly, conservative memers interpret her as conniving and untrustworthy. Finally, Figure 8 has caught her at a moment when she appears to be speechless. The implication behind this photo is that she has been found in a lie or is considering her next one. Notably, the text on all three fixates on her supporters, belittling their intelligence. The goal of these memes is twofold: to portray Clinton as old and ugly, and to call her and her supporters stupid.

Figure 6: Hillary Clinton Meme

Figure 7: Hillary Clinton Meme

Figure 8: Hillary Clinton Meme

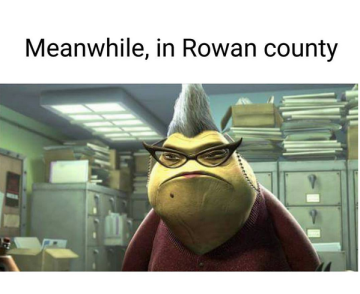

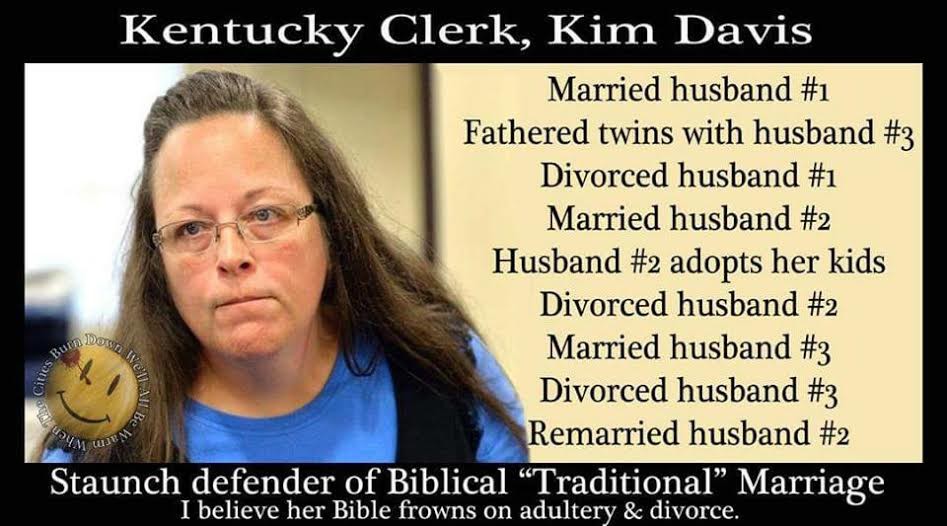

Although she is not photoshopped, Kim Davis received similar treatment for her appearance from progressive memers. Davis is not conventionally attractive, which many memes picked up as a central theme. Figure 9 pokes fun at her clothes, pointing to a style of outfit that she appeared in frequently when she was in the public eye. Figure 10 pinpoints her hair, joking that, since all good hair stylists are gay, she will never be able to find one willing to help her with her appearance.[4] Finally, Figure 11 deviates from the other two in that it does not depict Davis herself, but instead shows a still from the animated movie Monsters Inc that equates her to a slug-like monster with an imposing demeanor and a grating voice. Although the meme does not explicitly mention Davis’s appearance like the first two do, it draws an implicit connection between her and a cartoon to reinforce a negative argument about her level of attractiveness.

Figure 9: Kim Davis Meme

Figure 10: Kim Davis Meme

Figure 11: Kim Davis Meme

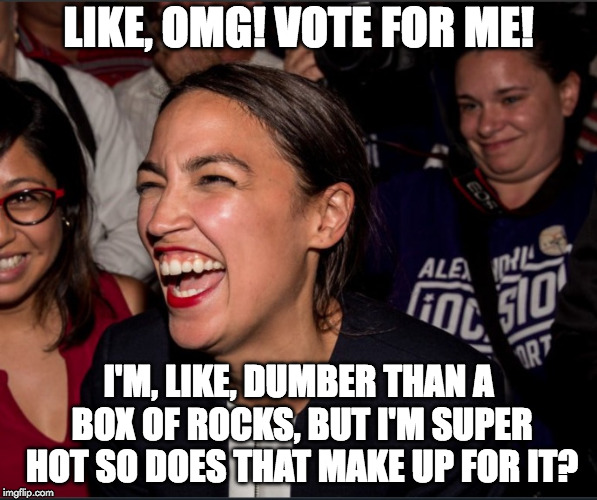

Not only do progressive and conservative memers ridicule women like Clinton and Davis, but they also target more conventionally attractive women. As a Latina, Ocasio-Cortez is depicted in memes alternatively as frightening, unintelligent, and hypersexualized. Like Clinton, Ocasio-Cortez is also animated and makes many facial expressions that conservative memers exploit in memes based on her appearance. However, when the subject is a young Latina, the critiques take on a different edge. Figure 12 most closely aligns with some of the Clinton memes. It depicts a screenshot taken at an unflattering moment where Ocasio-Cortez is visibly excited, photoshopping her over Jack Torrance in the famous “here’s Johnny” scene from The Shining, which, coupled with the “here’s commie” text, makes her appear to be forcing Communism into the viewers’ homes. Figures 13 and 14 vary from this idea by focusing instead on her attractiveness. Also like the Clinton memes, Figure 13 connects attractiveness to intelligence, showing her laughing animatedly, while presenting text that makes her sound like an airheaded teen and explicitly referencing that she is “super hot.” Figure 14 takes this one step further by tapping into the tired stereotype that Latinas are hypersexual and available for consumption by men. What is interesting about this meme is that the image selected for the background is relatively unremarkable, both in comparison to Figures 12 and 13 specifically, but also to most AOC memes generally. She is smiling pleasantly and wearing a white button-up, in contrast to her animated expressions in the other two.

Figure 12: Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Meme

Figure 13: Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Meme

Figure 14: Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Meme

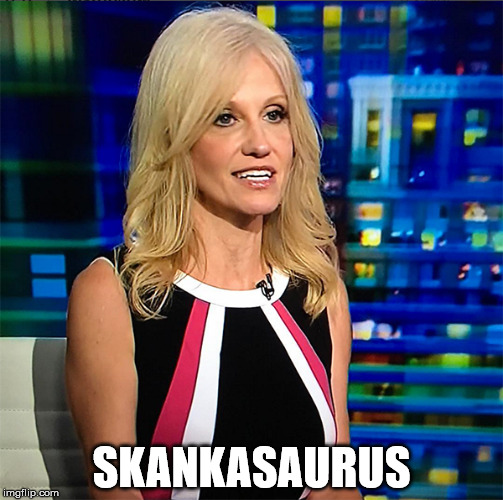

Finally, Kellyanne Conway has received some of the harshest memetic treatment. While Ocasio-Cortez’s memes hit on tired and unsurprising—yet still harmful—stereotypes about Latina women, Conway memes combined some of the harsh ridicule and cartoon comparison of the Davis memes with the intelligence mocking of the Clinton ones. Figure 15 depicts a comparison of Conway to Beavis from Beavis and Butthead, but this is not the only meme like this; I also could have chosen ones that compare her to ET from ET, the alien from Alien, Gollum from Lord of the Rings, or any other number of goblin-like creature. Figure 16 presents a fairly unremarkable image of Conway but is accompanied by one word: “Skankasaurus.” This trend of referring to Conway as sexually promiscuous—but also dirty, part of the connotative meaning of “skank”—appears frequently in memes about her. Figure 17 alters a photo of her, giving her red glowing eyes to make her appear evil, with text that implies she is a demon working for Lucifer to get Trump elected president.

Figure 15: Kellyanne Conway Meme

Figure 16: Kellyanne Conway Meme

Figure 17: Kellyanne Conway Meme

The deprecating humor in Figures 5-17 is rooted in demagoguery. As Roberts-Miller explains, “demagogic humor is generally mean, and doesn’t have the destabilizing effect that a lot of humor has (in which at least one part of the joke is on the person telling it)—it’s only about the out-group and their minions” (Demagoguery, 100). Clinton, Davis, Ocasio-Cortez, and Conway are not “in” on the jokes in these memes, and neither are their supporters. What’s interesting is that many of these memes don’t even try to hide behind the logic of lulz or use irony to distance themselves from their message in the way that image macro memes tend to. They explicitly denigrate the four women for the way that they look. These twelve memes point to larger trends in political memes depicting women as related to appearance. First, conservative memes about progressive women tend to focus on a connection between exaggerated facial expressions and intelligence. These memes imply that if a woman is animated, she must also be unintelligent. Second, progressive memes about conservative women tend to compare them to nonhuman things and fictional characters, such as cartoon slugs and monsters. By portraying them as monstrous, they literally dehumanize them. Finally, memes by and about both sides of the political divide draw specious connections between appearance and capability to explicitly suggest that women are unfit for politics.

The larger implication of these memes is that they uphold systemic beliefs that women need to be conventionally attractive to be allowed to be seen in positions of power, but if they are too conventionally attractive—or young, or Latina—they won’t be taken seriously. According to these memes, there is no appropriate way for a woman to look and be accepted in politics. And quite frankly, the jokes behind these memes aren’t even funny, or at least not particularly clever. These memes are akin to middle school playground insults and would likely only draw people with likeminded opinions. They are not meant to change anyone’s mind about Clinton, Davis, Ocasio-Cortez, or Conway, but only to reinforce the boundaries between those who like them and those who don’t.

2.2 Distracting or Irrelevant Information

I’ve spent quite a bit of space on appearance memes because they are some of the most visible, and in many ways most of the memes I’ll show for the next two sections also intersect with appearance, but with a twist of distracting or irrelevant information, or conspiracy theories or outright lies. I differentiate between the two for one key reason: distracting or irrelevant information is not necessarily untrue, even if it is diversionary, but conspiracy theories and outright lies are demonstrably and perniciously false. Memes with distracting or irrelevant information tend to push readers to draw misleading and untrue inferences, but unlike conspiracy theories or outright lies, they do not explicitly state them.

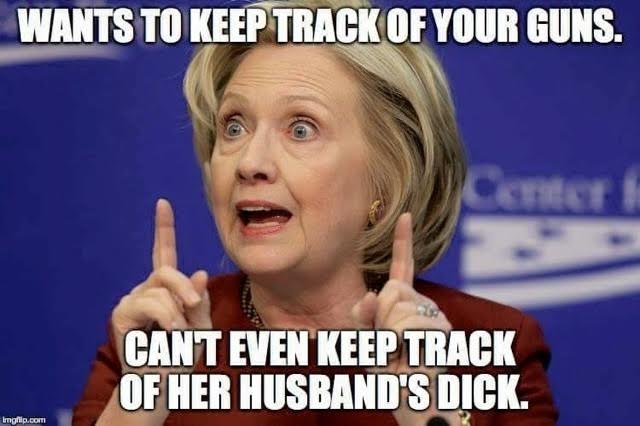

For Clinton, this style of meme often manifests in references to Bill’s infidelity. Figure 18 continues the trend of using photos of her at awkward moments, showing her holding up two fingers which, in connection to the text, make it look like she is referencing the size of her husband’s genitalia. The inherent, irrelevant claim is that her husband’s infidelity has made her unfit to be president. This is a powerful enthymeme with the unstated premise that any woman whose husband cheats on her is incapable of leading a country. Similarly, Kim Davis memes also reference infidelity, such as Figure 19, which is at least tangentially related since the issue at hand in the Davis incident involved the definition of “traditional marriage.” However, while pointing out her hypocrisy may have been satisfying for progressive memers, it was ultimately unproductive for digital discourse.

Figure 18: Hillary Clinton Meme

Figure 19: Kim Davis Meme

Distracting memes for Ocasio-Cortez tend to focus on her status as a democratic socialist, playing up the “socialist” part and even sometimes skipping right to Communism. Figure 20 overinflates the prices of her clothing, claiming that she spent several thousand dollars on an outfit that almost certainly did not cost that much. This meme came in response to a photoshoot she did where she was provided with a $3500 suit to wear, and conservatives contended that she was betraying the working class she claimed to represent by wearing an expensive suit. Ocasio-Cortez has taken to Twitter on more than one occasion to push back against conservatives who criticize her clothing choices, making it clear that she does not purchase expensive clothing. Behind this meme, however, is the implication that someone dedicated to the working class cannot dress in nice clothes, which has a further implication that working class people do not wear or deserve nice clothes themselves. Similarly, Conway has been singled out for her clothing choices, as Figure 21 demonstrates. This meme is one of many I could have chosen that ridicule her outfit choice for Trump’s inauguration in 2017; it compares her to Paddington Bear, but others drew connections between the Patriots’ logo, American Girl Dolls, and the Nutcracker, among many others. This type of meme is obviously closely tied to and overlaps with ones that fixate on appearance, but they also serve to distract from real issues. The meme for Ocasio-Cortez attempts to skew how people view her as a democratic socialist, and the one for Conway makes her seem goofy and outlandish, which distracts from her undeniable capability for cunning public deception.

Figure 20: Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Meme

Figure 21: Kellyanne Conway Meme

Like the memes fixated on appearance, these memes also provoke demagogic laughter while creating narratives that, through repetition across several memes, distract from political issues. They fixate on extraneous details: marriage infidelities and clothing choices have little to no bearing on political competence or capability, but these kinds of narratives tell us that they are connected to both. Mina explains that these narratives “hold power in our minds. The more a meme sticks, the more likely the deeper narrative sticks in turn” (117). Like the appearance memes above, these memes target their in-groups and solidify tightly held negative beliefs about each woman that should have no bearing on how we perceive their capabilities as women in political power.

2.3 Conspiracy Theories or Outright Lies

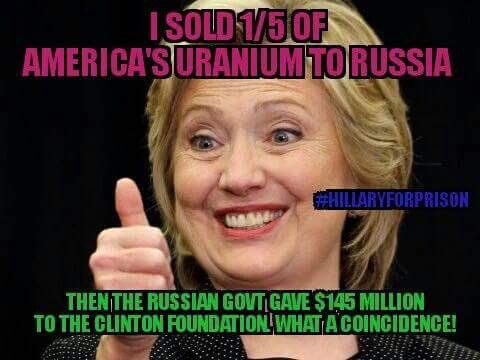

A third type of meme presents conspiracy theories or outright lies. These memes defy truth, deliberately spreading mis/disinformation about Clinton, Davis, Ocasio-Cortez, and Conway. As one of the most visible woman politicians of the 2010s, and as a former First Lady, there is no shortage of conspiracy theories focused on Clinton. Figure 22 is just one example, continuing to play on the trope of using awkward images of Clinton and focusing on the Uranium One deal with Russia, which both PolitiFact (Putterman) and Snopes (Emery) have denounced as false. Other examples I could have used include the Clinton/Podesta child pornography ring (also known as #Pizzagate) or the Clinton body count theory, both of which have numerous memes, and both of which are also demonstrably false. Some memes also spread outright lies. Figure 23 represents an example depicting Ocasio-Cortez with a list of “facts” about her, most of which are complete untruths. Some of them are true—such as “I want to impeach the president”—which makes this meme more insidious because viewers can easily connect the statements they know they’ve heard her make to the other false claims listed and take them all at face value. Ultimately, this meme also serves to perpetuate the false idea that democratic socialism is the same thing as socialism, which is the same thing as Communism and Nazism, and that democratic socialists are harmful dictators who will bring discord, famine, and authoritarian control to the masses.

Figure 22: Hillary Clinton Meme

Figure 23: Alexandria-Ocasio Cortez Meme

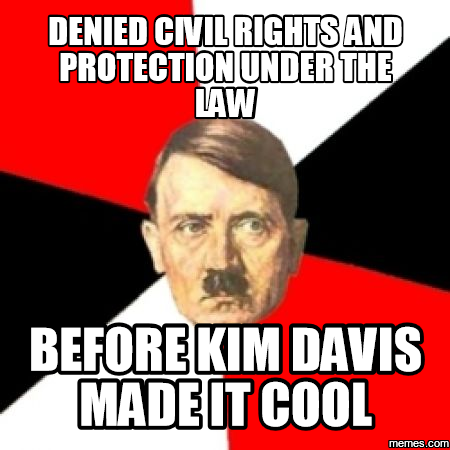

I classify another form of meme under this category as well: Nazi and Hitler comparisons. By drawing direct comparisons to a genocidal dictator and the people who acted on his orders, memers effectively shut out all opportunities for further dialogue. As Godwin’s Law states, “if you mention Adolf Hitler within a discussion thread, you've automatically ended whatever discussion you were taking part in” (Brad). Similarly, any memetic statement of a conspiracy theory or lie (such as Figures 22 and 23) tends to derail the conversation in a way that, according to conversations I’ve seen on Facebook, Reddit, Twitter, and other spaces, has a distinctly more contentious and hostile tone than some of the other kinds of memes.[5] Interestingly, while conservatives often equated Clinton to Hitler during the 2016 campaign—even going so far as coining the not-so-clever moniker “Hitlery”—usually progressive memes tend to be quicker to jump to Hitler and Nazi comparisons than conservative memes, although this is not monolithically true for all digital spaces. Figures 24 and 25 demonstrate how Davis and Conway have been compared to Hitler and Nazis in memes. The meme for Davis (Figure 24) focuses on a connection between Hitler dehumanizing people based on race, religion, and sexuality, while also downplaying it for humorous effect with the phrase “made it cool.” The meme for Conway pastes her head directly onto a Nazi soldier and depicts a quote about how people who oppose Trump will “face consequences,” implying that Trump is Hitler and she is a soldier who will carry out vague yet ominous punishments on his behalf.

Figure 24: Kim Davis Meme

Figure 25: Kellyanne Conway’ Meme

Like the memes focused on appearance and distracting or irrelevant information, these memes function demagogically. But these memes are especially dangerous because, as Ryan Skinnell has pointed out, during the 2016 election, “a significant proportion of the American electorate didn’t, and still doesn’t, believe professional fact checkers and the media” (77, emphasis mine). Roberts-Miller explains that the reason for this is because “we believe that in-group members are more likely to be honest, even objective, whereas out-group members are dishonest at worst and biased at best” (Rhetoric, 7). As such, these memes serve as a kind of propaganda, or a form of demagoguery that, as Jason Stanley argues, “exploits and spreads flawed ideologies” (5), while also serving as obstacles to democratic deliberation. Roberts-Miller argues that “When it’s effective, demagoguery persuades people to see beliefs, policies, and so on as ‘naturally’ deriving from who they ‘essentially’ are (good). The opposition’s arguments derive from who they essentially are (bad) and need not be taken seriously” (Rhetoric, 28). In the case of these memes, then, Clinton, Ocasio-Cortez, Davis, and Conway are portrayed as essentially bad, with the implication being that they are involved in deep Russian and Communist conspiracies or that they are Hitler-esque and will force their will on the masses.

Moreover, the rise of digital technologies has made it easier to create alternative narratives that can make it difficult to determine fact from fiction. Information overload makes people less likely to fact-check and instead trust familiar sources of information rather than verifying for themselves. People are exhausted and overwhelmed by disinformation. These memes propagating conspiracy theories and outright lies function similarly. Even despite how unrealistic some of these conspiracy theories sound, they drown out verifiable information in a sea of mis/disinformation. Viewers of these memes do not research the conspiracy theories or seek to uncover the lies, or any research they might have done ended when they encountered sources that did not match their worldview.

Notably, these memes also hinge on appearance to amplify their points. Clinton and Ocasio-Cortez have exaggerated facial expressions, a trademark of conservative memes that makes them appear wild and untrustworthy, and, while Davis is erased from her Hitler meme, Conway is made to look sinister and angry. This appearance-based memetic misogyny tied to conspiracy theories and outright lies allows progressives and conservatives to perpetuate harmful and essentializing cultural narratives and ideologies that keep them at odds from each other. Tryon argues that “Political memes preserve the ephemeral… [they] can have a galvanizing effect, bringing attention to the underlying meaning of comments that might have otherwise been ignored.” In other words, memes highlight moments that might otherwise get lost in a regular news cycle. These memes do not necessarily reflect the figure they represent, but they help define them (Tryon). In so doing, these memes not only solidify images and cultural narratives about political misogyny, but they also irrevocably connect these women to sexist representations that inaccurately define their ideas and stances and affect their public perception.

3. Conclusion: Where do we go from here?

There are many pathways forward from this analysis of memetic representation of women in politics. In the sections ahead, I offer three avenues for further research before turning to some strategies for resisting political memetic demagoguery.

3.1. Further Research: Russian Trolls and Bots

This analysis does not account for memes that may or may not have been made and circulated by Russian trolls and bots. Perhaps some of the memes I have analyzed here were created specifically to sow disruption and discord in U.S. politics. I collected most of these memes in 2015 and 2016 (with the exception of Ocasio-Cortez memes, which I collected mostly in 2018), well before it was revealed that Russia was meddling in our election, so at the time I was not aware of the need to distinguish between authentic and Russian memes. Even if I had been, a Vice quiz shows that differentiating between the two is difficult because the Russian trolls were (and probably still are) very adept at adopting U.S. cultural referents and meming techniques (Silva and Sterbenz). Rebecca Coates Nee and Mariana De Maio performed a quantitative content analysis of Hillary Clinton memes created by Russian trolls and determined that “negative female biological gender stereotypes were prevalent in memes of Clinton, portraying her as weak or unhealthy, attributes which are incongruent with leadership ideals. Memes relating to Clinton’s character traits were also incongruent with positive traditional female characteristics of honesty and integrity” (314). While this finding is significant, it is not the entire story. More research is needed to examine other political figures and an array of intersecting identities to determine the ways in which Russian memes play on tropes of American culture—even and especially those centered on race, gender, sexuality, disability, age, and other intersecting identity factors—to widen the party divide.

3.2. Further Research: Analog Political Memes

I’ve focused largely on digital image macro memes, but political meming also spreads beyond the digital. These analog memes can take many forms and can sometimes be connected to a digital counterpart. They often manifest as things like catchphrases, or they can be remixed onto material items like shirts or posters. These transformations among modalities and spaces is what makes them memetic; they shift and evolve as they move. During the 2016 U.S. presidential election and his entire presidency, Trump was a meme machine. In particular, the way he developed call-and-response tactics during his campaign speeches was reminiscent of the memetic behaviors I saw when I studied 4chan’s /b/ board where there seemed to be unwritten norms about how to respond when users say certain things (Sparby, “Digital Aggression”). At certain points during his rallies, Trump would say something about Mexico, and his supporters would shout “build the wall.” Most relevant to this study, whenever he would mention Clinton, they would chant “lock her up.” This became a memetic rallying cry both at and beyond the gatherings and it seeped its way into national narratives about Clinton that had little to do with the election. It was memetically remixed to slogans like “Hillary for prison” and became buttons, t-shirts, bumper stickers, and all manner of other analog memetic material. It has echoes in similar memes like calling Clinton “Crooked Hillary” and “Hitlery.” And this meme has staying power. People were still chanting “lock her up” as recently as 2019—about not only Clinton but also other women who oppose Trump. Memetic chants like these serve as demagogic narratives that distract and divide. Further research is needed into how these analog and digital memes connect and intersect to create a memetic political culture that influences how we decide to vote.

3.3. Further Research: Generational Meming

Memetic production and circulation seem to differ by generation. I say “seem to” because this statement stems from periphery observations I made while researching the memes above. The most obvious distinction I noticed was between Millennials’ and Gen Z’s use of image macros. While Millennials tend to gravitate toward a format that uses top and bottom text in impact font, younger users tend more towards sharing screencaps of tweets (itself a memetic behavior) or making more nonlinear textual memes. Similarly, Boomers primarily tended toward text-heavy memes with spelling and punctuation errors. I almost didn’t include this topic as a suggestion for further research because the preliminary observations I made align so closely with generational stereotypes, but the rise of the “Ok Boomer” meme in late 2019 shows that it may be a worthwhile area of examination to understand the implications of generational meming for politics and digital discourse.

3.4. Toward Strategies for Memetic Resistance against Demagoguery

I return now to the question I brought up near the beginning: how can we have civil dialogue if the memes we encounter daily only reinforce the beliefs we already have? Put simply, we can’t. Far from offering opportunities for dialog and debate, these demagogic memes only strengthen the in-groups while alienating the out-groups. They polarize and preclude the possibility of the two sides reconciling their perspectives and engaging in meaningful discussion. This is the issue at the core of political meming. While they spread mis/disinformation, the larger problem of these political memes is their ability to divide us, regardless of party or political affiliation. It’s no coincidence that these memes are also rooted in misogyny. They reveal that no matter what your party affiliation, women are still considered inferior political figures to men because they continue to be held to cultural narratives and expectations related to likeability and appearance[6]. And I think this is an important point to stress: both progressives and conservatives are equally culpable for producing memes that distract and misinform through misogyny. So what do we do about it? This is a big question and it doesn’t have an easy answer, but I have two suggestions to get us started.

The first is pedagogical. We should be teaching and talking about memes in our classes. It is our ethical obligation to help students become “good digital citizens” by addressing technological literacy and its link to citizenship and democracy. As Cindy Selfe has explained, this technological literacy means we must think critically about the media we consume and produce, we must take informed positions on complex issues, and we must listen—and listen rhetorically via Krista Ratcliffe—to opposing viewpoints. And we must do all of this in a variety of digital spaces across a range of media. Through looking at this small sampling of how memes can be used as dangerous misogynistic political tools, it becomes clear that this technological literacy must include memes.

In addition, this technological literacy must include circulation practices. It’s one thing to create a meme and post it in a space where it will circulate briefly around a few users; it’s another when a meme goes viral and breaks out of its initial community. As such, teaching students about concepts like Jim Ridolfo and Dànielle DeVoss’s rhetorical velocity is key. In addition, as Brandy Dieterle, Dustin Edwards, and Dan Martin argue, users need to be critical of their own circulation practices. When a user reshares or retweets content, such as memes, they serve as another cog in a machine that perpetuates it. Regardless of if they add critical commentary or not, reshared memes can reinforce political misogyny and mis/disinformation by keeping the content in circulation. The irony is not lost on me that even in this academic context I am doing exactly this by displaying the memes about which I speak, but I am also doing so critically to help us understand the shape of the problem, which, as Whitney Phillips has argued, is important to studying harmful discourses online.

This brings me to my second suggestion. We need to be critical of the content we show and share in our academic contexts. This is an especially pressing concern in digital aggression studies, where we question—or at least, should question—whether we will show screencaps or provide direct quotes of aggressive content, or if we will summarize it. The same goes for these memes. I’m not saying don’t show them; I’m saying do so intentionally and have a good reason for it. I ultimately decided to share images of the memes in this article because memes are highly visual and this visuality is part of my analysis and argument, but I also intentionally avoided some of the more violent and sexual memes that can be, quite frankly, disturbing. As part of my decision about which memes to analyze and display here, I decided I could make my argument effectively without showing or even referencing the disturbing ones. In addition, those of us who are content producers need to be critical of what we make and how we circulate it. We especially need to be aware of Poe’s Law of the internet and that irony can come across as sincerity in certain contexts.

As a field, we’ve been slow to catch up with the pervasiveness of memetic media, in large part because we didn’t really take it seriously at first. We saw memes as mundane texts with little bearing on the “real world.” We’re starting to catch up, but memes travel fast, and we have a lot more work to do. This analysis provides a glimpse of what we can learn from studying political memes and how cultural narratives of misogyny can spread and reinforce mis/disinformation. More work is needed to fully understand what memes are capable of and how instrumental they are in polarizing political parties, especially at a time when everyone needs to be listening to and learning from each other.

Notes

[1] Although he has also said in a Wired interview that today’s memes are not quite what he intended (Solon). Memes change, mutate, and evolve naturally through the act of sharing, he argues, but internet memes are actively and intentionally altered, making them not quite “memes.” Regardless, it seems that billions of internet users have outvoted Dawkins, and the term stands.

[2] Poe’s Law is an internet axiom stating that unless an author clearly expresses their intent, it’s impossible to distinguish satire of extremism from authentic expression (Tomberry).

[3] Internet scholars like Axel Bruns have argued that the terms “filter bubble” and “echo chamber” are unproductive both because they imply an isolation of viewpoints and experiences that platforms and algorithms do not realistically deliver, and because they place blame on technology instead of working against societal issues that perpetuate injustices. However, I disagree with this reduction. In my work I’ve recognized the impact of people cultivating their own feeds on social media to mitigate context collapse (choosing to unfollow someone whose content you don’t want to see, for instance). I’ve also come to appreciate that blaming technology is productive because it can lead us to understand and change the forces of production behind it (Wachter-Boettcher). As such, I find these terms—particularly in the context of memes and meme communities on Facebook and Reddit—to be useful ways to discuss the ways these memes circulate in insular communities where people who largely already support their ideologies are the most likely to see and comment on them.

[4] This meme is interesting because, while implicitly defending the right for same-sex couples to marry, it also reinforces a potentially harmful stereotype of male hair stylists being gay.

[5] More research is undoubtedly needed into the distinction between the impacts of these kinds of memes on digital conversations.

[6] This article was written and submitted in late 2019, so the Bernie Bros’ problematic attacks on Elizabeth Warren had not yet heated up, but their anti-Warren memes continued this theme of misogyny until she suspended her campaign in early March 2020. One of the most significant moments was when Twitter users tweeted the snake emoji at her (a memetic behavior), accusing her of lying about a private conversation with Sanders where he allegedly said he didn’t think a woman could win against Trump. The image of a snake has roots in the Adam and Eve story that blames woman for original sin and human suffering.

Brad. “Godwin’s Law.” Know Your Meme, 2009, https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/godwins-law. Accessed 16 Dec 2019.

Bruns, Axel. “It’s Not the Technology, Stupid: How the ‘Echo Chamber’ and ‘Filter Bubble’ Metaphors Have Failed Us.” IAMCR 2019 Conference, July 2019, Madrid, Spain. Conference paper, http://snurb.info/files/2019/It%E2%80%99s%20Not%20the%20Technology%2C%20Stupid.pdf. Accessed 29 June 2020.

Coates Nee, Rebecca, and Mariana De Maio. “A ‘Presidential Look’? An Analysis of Gender Framing in 2016 Persuasive Memes of Hillary Clinton.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, vol. 63, no. 2, 2019, pp. 304-321.

Dawkins, Richard. The Selfish Gene. Oxford UP, 1976.

DeCook, Julia R. “Memes and Symbolic Violence: #proudboys and the Use of Memes for Propaganda and the Construction of Collective Identity.” Learning, Media and Technolgoy, vol. 43, no. 4, pp. 485-504.

Dieterle, Brandi, et al. “Confronting Digital Aggression with an Ethics of Circulation.” Digital Ethics: Rhetoric and Responsibility in Online Aggression, edited by Jessica Reyman and Erika M. Sparby, Routledge, pp. 197-213.

Emery, David. “Did Hillary Clinton Give 20% of United States’ Uranium to Russia in Exchange for Clinton Foundation Donations?” Snopes, 16 Nov 2017, https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/hillary-clinton-uranium-russia-deal/. Accessed 16 Dec 2019.

Huntington, Heidi E. “Pepper Spray Cop and the American Dream: Using Synecdoche and Metaphor to Unlock Internet Memes’ Visual Political Rhetoric.” Communication Studies, vol. 67, no. 1, 2016, pp. 77-93.

Milner, Ryan. “Hacking the Social: Internet Memes, Identity Antagonism, and the Logic of Lulz.” The Fibreculture Journal, vol. 22, 2013, pp. 62-92, http://twentytwo.fibreculturejournal.org/fcj-156-hacking-the-social-internet-memes-identity-antagonism-and-the-logic-of-lulz/. Accessed 16 Dec 2019.

---. “Pop Polyvocality: Internet Memes, Public Participation, and the Occupy Wall Street Movement.” International Journal of Communication, vol. 7, 2013, pp. 2357-2390.

Mina, An Xiao. Memes to Movements: How the World’s Most Viral Media is Changing Social Protest and Power. Boston, Beacon P, 2019.

Pariser, Eli. The Filter Bubble: How the New Personalized Web Is Changing What We Read and How We Think. Penguin, 2012.

Phillips, Whitney. This is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things: Mapping the Relationship Between Online Trolling and Mainstream Culture. MIT P, 2015.

Putterman, Samantha. “Complex Tale Involving Hillary Clinton, Uranium and Russia Resurfaces.” PolitiFact, 7 Dec 2018, https://www.politifact.com/facebook-fact-checks/statements/2018/dec/07/blog-posting/complex-tale-involving-hillary-clinton-uranium-rus/. Accessed 16 Dec 2019.

Ratcliffe, Krista. Rhetorical Listening: Identification, Gender, Whiteness. Southern Illinois UP, 2005.

Ridolfo, Jim, and Dànielle N. DeVoss. “Composing for Recomposition: Rhetorical Velocity and Delivery.” Kairos, vol. 12, no. 2, 2009, http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/13.2/topoi/ridolfo_devoss/intro.html. Accessed 16 Dec 2019.

Roberts-Miller, Patricia. Demagoguery and Democracy. The Experiment, 2017.

---. Rhetoric and Demagoguery. Southern Illinois UP, 2019.

Selfe, Cynthia L. Technology and Literacy in the Twenty-First Century. Southern Illinois UP, 1999.

Shifman, Limor. Memes In Digital Culture. MIT P, 2014.

Silva, Christiana, and Christina Sterbenz. “Bot or Not: Can You Tell Which Memes Came From Russian Trolls?” Vice, 11 May 2018, https://news.vice.com/en_us/article/kzke89/quiz-can-you-tell-which-memes-russian-trolls-posted-to-facebook. Accessed 16 Dec 2019.

Skinnell, Ryan. “What Passes for Truth in the Trump Era: Telling It Like It Isn’t.” Faking the News: What Rhetroic Can Teach Us About Donald J. Trump, edited by Ryan Skinnell, Societas, pp. 76-94.

Solon, Olivia. “Richard Dawkins on the Internet’s Hijacking of the Word ‘Meme.’” Vice, 20 Jun 2013, https://www.wired.co.uk/article/richard-dawkins-memes. Accessed 16 Dec 2019.

Sparby, Erika M. “Digital Social Media and Aggression: Memetic Rhetoric in 4chan’s Collective Identity.” Computers and Composition, vol. 45, 2017, pp. 85-97.

---. Memes and 4chan and Haters, Oh My! Rhetoric, Identity, and Online Aggression. 2017. Northern Illinois U, PhD Dissertation.

Stanley, Jason. How Propaganda Works. Princeton UP, 2015.

Tomberry. “Poe’s Law.” Know Your Meme, 2011, https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/poes-law. Accessed 16 Dec 2019.

Tryon, Chuck. “The Power of Political Memes.” The Week, 2016, https://theweek.com/articles/644312/power-political-memes. Accessed 2 July 2020.

Vie, Stephanie, “In Defense of ‘Slacktivism’: The Human Rights Campaign Facebook Logo as Digital Activism.” First Monday, vol. 19, no. 4, 2014, http://firstmonday.org/article/view/4961/3868. Accessed 16 Dec 2019.

Wachter-Boettcher, Sara. Technically Wrong. Norton, 2017.

Wall Street Journal. “Blue Feed, Red Feed.” 19 Aug 2019, https://graphics.wsj.com/blue-feed-red-feed/. Accessed 16 Dec 2019.

Weatherbee, Ben. “Picking Up the Fragments of the 2012 Election: Memes, Topoi, and Political Rhetoric.” Present Tense, vol. 5, no. 1, 2015, http://www.presenttensejournal.org/volume-5/picking-up-the-fragments-of-the-2012-election-memes-topoi-and-political-rhetoric/. Accessed 16 Dec 2019.

Wiggins, Bradley E. The Discursive Power of Memes in Digital Culture. Routledge, 2019.

Woods, Heather Suzanne, and Leslie A. Hahner. Make American Meme Again: The Rhetoric of the Alt-Right. Peter Lang, 2019.