Jessica Schriver, Rutgers University-Camden

(Published November 18, 2019)

This kit is a reworking of a course project. In the first assignment prompt for Dr. Jillian Sayre’s “Significant Otherness” course at Rutgers University-Camden, we were asked to create a project that took up body modification as a vehicle for understanding posthumanism. Readings leading up to the assignment exposed us to some foundational texts of posthumanism, including Donna J. Haraway and N. Katherine Hayles; a digital encounter with Stelarc’s body mods; and a critical reading of Katherine Dunn’s Geek Love. With these texts in mind, we were tasked with producing a “speculative body project as an analytical lens to understand the ways in which theories of posthumanism confront the body.” A key component of the assignment was to consider performance or display, encouraging imagined viewers as participants in the scheme. Traces of that call for participation turned what was a singular project into the prosthetic womb kit, whereby participants aren’t just “viewers” but now makers too.

In responding to Sayre’s call, I produced a prosthetic womb: a thing both of the body and not of the body. In collapsing the distinction between body-modification (mechanical, cyborg) and body-woman (fleshy, organic), the prosthetic womb complicates notions of who can be a mother by redefining motherhood as a category of gestation rather than of sex or fertility. Men can be mothers. Women can be mothers. Further still, the womb is not just for human gestation. Motherhood can be shared with kittens or hamsters, sparking challenges to kinship and heredity. Not just who may be mother, but be mother to what.

Womb Making

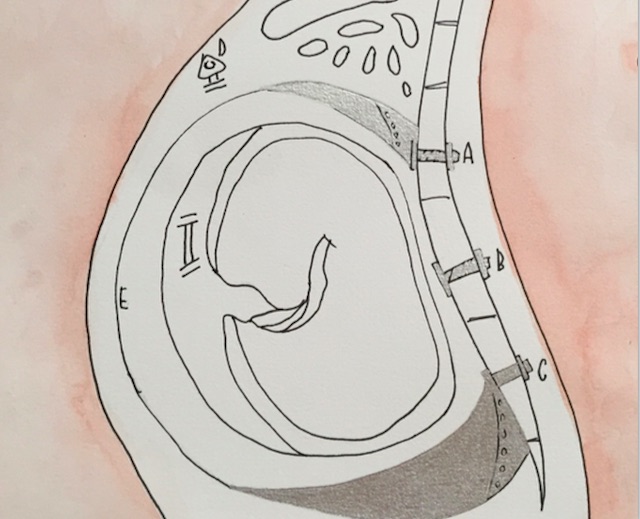

Using watercolors and ink, I drew and painted a head that resembled no one in particular, and a body so generic that the head, in many ways, is interchangeable or ancillary. Using anatomy resources, I sketched out a simple human skeleton, pairing the starkness of bare bones with soft pinks and warm tones to invoke the obligatory tropes of motherhood: softness, warmth, feminine. The colors also serve to bring the inside out: the colors of wombs and sex organs. When it came to representing the womb, I used metallic pens to color the metal implants silver, and I added a piece of wax paper—a bit transparent and, symbolically important, an article found in the domestic sphere—to mimic the look of stretchable rubber surrounding the prosthetic uterus.

Figure 1. Illustration from the Enfreaked Wombs Digital Booklet

Once I completed the figure, I chose to sever the body, to dissect the assumed wholeness and naturalness of motherhood, thus critiquing constructions of motherhood as a process that makes a woman “whole”. I then glued the segments into a picture frame, open to fingers to touch, encounter, and play with these pieces of motherhood.

The prosthetic womb kit invites makers to cut and configure the body. The body provided is not pregnant, perhaps not even fertile by nature. It is the implantation of the prosthetic womb that quickens the form. Assembling the kit adds a new participatory facet to the project, as participants are making wombs, not just viewing wombs. This involvement reflects the ways in which gestation is both an activity and a spectacle. Kit makers answer the question of what to gestate: human or non-human? Fetal ultrasounds let makers share gestational news.

In addition, the figure is missing anatomical layers: of skin and breasts, specifically. The openness of the form welcomes investigation, as a means of moving beyond the opaqueness of the pregnant body. Foregrounding the internal workings of the pregnant body challenges traditional expectations of pregnant bodies as whole or holy, sacred or secret. This is a medical exhibition, challenging social constructions of motherhood.

Motherhooding

Having moved beyond the womb as a space for family creation, humanity maintains adoption and IVF as acceptable alternatives. As a space deemed sacred and mysterious, the female form is, at times, considered ideal for and limited by gestation. Wider hips, mammary glands, a uterus: all of these feminine attributes have either been replaced or can be replaced. Narrow hips can be worked around with a surgical birth. Difficulty breastfeeding leads to bottlefeeding. Lack of reproductive organs just requires renting another woman’s body. These alternatives to natural birth have been embraced by the public, even replacing the original at times. So what, then, is holding back humanity from embracing the prosthetic womb?

As Haraway notes, “the boundary between human and animal is thoroughly breached…nothing really convincingly settles the separation of human and animal” (293). “Breached” is a keyword in her exposition. Although breaching implicates a breaking through of defensive walls, it also recalls the natural activity of whales wholly breaking the surface of the water (“breach”). The vision of a whale’s body leaping above the waterline is awesome and powerful, perhaps even terrifying. These powers of nature, often passed off as objects of wonder rather than subjects of thought, give man the dividing line he needs to feel comfortable. But Haraway refuses to abide by this unnatural division. Haraway’s carefully crafted vocabulary points to the natural world tearing at the defenses of humanity, rather than humans tearing into nature..

Haraway goes on to describe the identity of women as fractured. She writes, “There is nothing about being ‘female’ that naturally binds women” (295), including the state of motherhood. Pointing to the split nature of feminism, Haraway denounces the search for “essential unity” (296). If the essentialness of motherhood cannot unite women, what may be left? Unless, of course, motherhood is not essential, making a unity via essentialness impossible. Instead, Haraway argues for “affinity, not identity” (296). Connection is what Haraway sees, not the disconnection that identity produces, as she writes, “affinity: related not by blood but by choice, the appeal of one chemical nuclear group for another” (295). This connection is not built on labels of species, genus, or DNA, but relies entirely on a shared atomic makeup.

Which is what this experiment is meant to ponder: the connection not just between mother and offspring, but of mothers—as men, women, animal, etc.—as no longer answers to different questions, but as different answers to the same question:

Are you a mother? Yes. I am a mother of ______________.

Mother no longer carries the weight of gendered identity or the experience of reproduction. Open for all to experience, regardless of internal organs, the prosthetic womb allows humans to choose to engage their bodies in the production of their offspring and choose who (or what) to mother.

How to Make a Baby

Katherine Dunn’s novel Geek Love, beautifully detailing the freaky and embodied experience of reproduction, is the seed of the prosthetic womb kit. The novel follows a family of intentional freaks who put on and perform in a circus. What sets this family apart are Lil and Al who made their children (Arty, Oly, Iphy, Elly, and Chick) freaks through carefully crafted in utero experiments, injecting Lil with “illicit and prescription drugs, insecticides, and eventually radioisotopes” during her pregnancies (Dunn 7). Rather than leave abnormality to happenstance, Lil and Al make their offspring freaks, in part to insure their economic power. However, all of those experiments left Lil’s health compromised.

So intimately tied to her offspring, Lil’s choice to enfreak her children came at extreme physical and personal costs. But Lil’s experience is not so far from the experience of typical pregnancy, as bodies change and stretch and some women are injured or die. Highlighting the connection between the body and reproduction through Lil’s experiments showcases the ways in which pregnancy is always at a cost of the impregnated body. The prosthetic womb severs some of these physiological connections, thus showcasing the physical and personal consequences of reproduction.

Lil’s connection to her offspring is explained in the story as each day, Lil “would take her pills after breakfast and then go over the Chute with her cleaning gear…to visit the ‘kids’ as she called them” (Dunn 53). Lil is reminded daily of her motherhood as she is tied to a daily pill regiment to maintain her health, thanks to her self-induced experiments in procreation. But also, the Chute, as the home for those children who were unable to survive the mix of chemicals (or the jealousy of siblings), becomes another reminder of Lil as a natural mother and a mark of her identity. Each jar displaying the remains of those unsuccessful births were labeled “’Born of normal parents’” (54). It was with pride that Lil put her birth canal, the Chute, on display for visitors to appreciate her identity as mother. However, Al, as father, was not as invested in the Chute; Oly notes that Al “never went to the Chute himself” (55)—a noticeable absence to the narrator. Al’s distance from the Chute stems from a lack of intimacy and affinity for the children he felt he never connected with. Although they incorporate his bloodline, he has chosen to disassociate himself as father of these jarred creatures. And his abandonment is accepted, because only a mother could love a “lasagna pan full of exposed organs with a monkey head attached” (54). So much of fatherhood for Al relies on the post-natal, on experiencing the child, not the fetus. It is little wonder that Al distanced himself from these jars; he was left out of that pre/peri-natal experience. He was never mother.

Techno-Mom

In My Mother Was a Computer, N. Katherine Hayles reconsiders mother as alluding to the displacement of Mother Nature by the Universal Computer. Just as Mother Nature was seen…as the source of both human behavior and physical reality, so now the University Computer is envisioned as the Motherboard of us all. (3)

Natural birth not only becomes a source of praise, but of blame, so that when human behavior or physical reality miss the mark upon birth, the mother is often the culprit. Eliminating Mother Nature from the mother process also removes the culture of blaming and shaming, while simultaneously granting control to the impregnated to differentiate between what is done to the mother body and the fetus form.

Where I believe that Hayles raises a key question of the mother experience is in the voice. She writes, “the voice most people heard was the same voice that taught them to read, namely, the mother’s, which in turn was identified with Mother Nature and a sympathetic resonance between the natural world and human meaning” (4).

She goes on to note that the sounds of the computer have replaced the voice of the mother; in that sense, the disconnect from the natural world mirrors that of this project. The mother’s voice becomes not the biological voice of the woman who donated an egg to your existence, but instead to the body that you call home for the period of your gestation, natural or otherwise. As Timothy Morton explains, “the intimacy afforded to me by its haptic nudging, reminds me not of its constant presence, but of its withdrawnness” (69). Although motherhood is intimate, it is also predicated on eventual separation. In this separation, the mother may be reminded of the shared intimacy, the closeness of those forms. In some ways, they are considered an object singular; in others, two separate objects. The prosthetic womb plays into this tension, by making the womb of a body—an intimacy, constantly present (in Morton’s frame), but also not of the body’s natural systems—withdrawn in its origins. One way to examine and experience this gap is through the sensuous, Morton’s “haptic nudgings.” As the sounds of the mother shake her body, the offspring shares in the physical motion. The first experience of something beyond the womb relies on sound waves, as the other senses are obscured or undeveloped. Vibrations communicate, without the damaging restrictions of language, the experience that awaits the offspring via the mother: A true affinity, bound not by blood or DNA, but by the collective event of two co-existing organisms.

Pregnant & in Pieces

Emily Martin talks about the fractured nature of the woman’s body in The Woman in the Body. Women who gave birth via cesarean describe “feelings of fragmentation and objectification…and describe feeling forcibly violated” (84). Martin continues: “These women are putting into words a feeling of alienation between themselves and the event of the cesarean section, akin to the alienation of the laborer from his or her work” (84). Martin’s argument explains the curtaining off of the lower portion of the body in doctor’s visits and even labor itself. Physically disconnecting a woman from her birth experience is a dis-empowering move, molding the woman into a passive object in her child’s birth.

I think Martin is right to see and call out this fragmentation, but I think this split extends beyond the labor room. It moves into home and work life, too, domains in which women are asked to fragment their being into employee and mother, separate modes of performance. And it seems expected that these two personalities should now overlap: bringing baby into work will only damage productivity and bringing work home will only damage baby. How are women expected to feel whole in child birth when what faces them after birth is a future of split personalities?

Birth plans play a complicated role in women’s agency. Kim Hensley Owens’ Writing Childbirth: Women’s Rhetorical Agency in Labor and Online tracks the ways in which women attempt to gain agency and power over their mothering bodies. These plans may address pain medication preferences, mobility preferences, food options, and other potential decisions made by the mother prior to entering the hospital. Through writing birth plans and sharing stories online, Owens argues that women choosing home birth or c-section, or those women who want and trust the hospital experience, typically do not write birth plans. But birth plans aren’t the final answer to control or agency. Women choosing to forgo birth plans are not necessarily giving up control or autonomy, since writing a birth plan does not guarantee adherence. Emergencies, or even just a change of mind, might void a carefully crafted birth plan. Rather than situate agency in the totality of a plan, what if we read birth plans as kits, as the attempt to assemble a narrative from the many pieces of reproduction? Instead of locating agency in the production of a birth plan, we might locate the itemized agency of reproduction. Like the prosthetic womb kit, reproductive agency is both the assembling and the assemblage.

Reading through Owens, I kept hearing the call of the cyborg in my head. The assemblage quality of the cyborg in particular, as “a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction” (Harraway 291), reminds me of Emily Martin’s fragmentation and Owens’ unity. Women through childbirth experience the taking-apart of themselves not only by intervening medical professionals, but the fetus, too: the splitting and joining of cells, thousands of times over, growing and mutating into a recognizable human. And then, the growing belly as an appendage to her body, never quite part of her, but always attached to her. And then, of course, there is the final separation: childbirth, where the “unborn child who is not herself and another as her creative paradigm” (Higgonet 201) is now just the other.

Anne Higgonet claims that in art “the mother’s role is not so much to engage with the child, but to cue our visual engagement” (112). Although Higgonet is using this argument when dealing with static images, I see this as an applicable claim to the real bodies of mothers. The pregnant body, on view, acts as an invitation to access the child-to-be. Those viewing the body ask questions, have urges to touch the body, and give advice as a means of engaging with the child-to-be. The mother is simply there to answer the questions, permit the touches, and accept the advice graciously. There is an interplay here of connection and disconnection of which birth makes for perhaps the ultimate expression: the separation of mother and child, and the biological, physiological, physical, and emotional connections to come.

Pregnant & Deviant

In reading Timothy Morton’s contribution to Objected Oriented Feminism, “All Objects are Deviant,” I find myself considering the pregnant body as both a demand for normalcy and yet, by virtue of its “thingness,” deviant.”

“A thing is a set of other things that do not sum to it,” writes Morton (67). The body that the other’s body creates is not the mother, is not even wholly of the mother, but of another’s DNA, too. Pregnancy may, culturally or socially, make a woman whole, but pregnancy is never a wholeness, but a series of gaps or “rifts,” in Morton’s terms. “This gap cannot be located anywhere…I can travel all around the surfaces and depths of a thing…and I will never be able to locate the Rift” (67). Images of pregnant woman revel in wholeness. Celebrities and lay people alike pose for maternity photoshoots, exposing pregnant bellies, mistaking fullness for wholeness. Yet, when bodies are not female, adult, or white, the pregnancy is not considered “whole.” As Dorothy Roberts writes,

Not only were Black women exiled from the norm of true womanhood, but their maternity was blamed for Black people’s problems. Contrary to the ideal white mother, Black mothers had their own repertory of images that portrayed them as immoral, careless, domineering, and devious. (10)

Transgender pregnant bodies, of trans-men ballooning with baby, may be read as merely large or fat. Black women’s bodies may be read as system burdens or discussed in degrading terms associated with family assistance services. Teen pregnant bodies are labeled as lacking childhood. It is only those white, Western women’s bodies that produce wholeness. “All objects are deviant insofar as they exist in difference from themselves,” Morton explains. “This is because they are riven from within between what they are and how they appear” (73). The prosthetic womb, inserted and invisible, keeps Morton’s Rift invisible, demanding more than a look to understand the gaps, chokes, and trips happening inside the growing belly. “When I handle a thing,” writes Morton, “I can never see it all at once” (68).

Future Birthing

Anne Pollock, in her chapter for OOF, raises concerns about the primacy of futurity in her chapter, “Queering Endocrine Disruption.” When considering the damage of toxins to Native American women, Pollock posits:

The unborn carry a troubling primacy over the already here. Women appear in these arguments as vessels for the next generation, rather than as people who matter to themselves and their present communities. It is all about the ability to reproduce, not the ability to live. (194)

By asking women—and even more so, girls—to always consider the future through an other, the present is never available. Girls are given dolls to learn how to be future mothers; women are admonished for drinking in bar bathrooms across the United States. The pressure of the future has been part of her life. A prosthetic womb troubles that gendered futurity by (1) inviting men to gestate futures and (2) gestating non-humans. What does a present look like when the burden of futurity is shared across genders and species?

The Othering of Mothering

After turning in this assignment to Dr. Sayre, I later went on to recast it into a research poster for a university research-sharing program. Again, I pulled out my watercolors, enlarging the diagrams and layering the poster with materials to juxtapose the softness of my painting with the manmade metals and plastics holding the poster together. As required, I stood next to my poster, ready for questions and comments. I tracked the comments I received on Twitter in real time and appreciated this time to gather feedback on the prosthetic womb (@awombofonesown). Results were mixed; at least one woman appeared offended. Another told me someone had told her about the project and that’s why she stopped by. Still another challenged me to think of non-Western wombs.

The feedback from this program, combined with additional research, has forced me to reconsider the prosthetic womb as not simply about motherhood, but about white motherhood. As a project of assembly/disassembly, the invitation to sever a woman’s body is a violence couched in the playfulness of childhood inventions. To freely question what is so human about human reproduction is an uncomfortable question, intended to take seriously the silliness of play and its ability to construct gendered narratives. The body reproduced here is white, and that is an intentional space, too. As Dorothy Roberts argues in her book Killing the Black Body, the story of reproductive rights in America has “a long experience of dehumanizing attempts to control Black women’s reproductive lives” (4). To create a project that asks to pick apart the body of a black woman is a violence happening in real ways everyday. “Black women are three to four times as likely to die from pregnancy-related causes as their white counterparts, according to the C.D.C.” (Villarosa) and it has taken celebrity athlete Serena Williams’ near-death childbirth experience to publicly expose the racism of reproductive medicine (Salam).

Although this project started as a playful consideration of what makes a womb a woman, has morphed into a question of who gets to live to be a mother? The United States has a woefully high rate of maternal mortality. The CDC reports “an estimated 700-900 maternal deaths” in the United States, plus “more than 50,000 potentially preventable near-deaths…per year” (Villarosa). California has become a leader in attending to these numbers, with Renee Montagne noting that “since 2006, California has cut its rate of women dying in childbirth by more than half” by creating their own kits: “toolkits that contain everything needed to tackle an emergency complication, from checklists to equipment to medications” (Montagne).

(Re)Make This Kit

Cyborg heroes and heroines are celebrated for their ability to leave the ‘meat’ behind by ‘jacking’ the body into cyberspace. Their creativity and agency in fashioning new bodies through customization often gives them a competitive edge. (Pitts 155)

With only so many natural, viable wombs to populate the planet, fertile women often find their reproductive decisions usurped by politicians, religious leaders, mothers-in-law, etc. By no means a new story, the womb rhetoric of 100 years ago is not so far from current discussions surrounding the female body. President Theodore Roosevelt, in a speech before the National Congress of Mothers (March 13, 1905), proclaimed, “a good mother, [is] able and willing to perform the first and greatest duty of womanhood…to bring up as they should be brought up, healthy children...numerous enough so that the race shall increase and not disappear.” Couched in exaltations of honor and the importance mothers’ work, Roosevelt’s words bind the female body to the womb, and the womb to the duty of a nation. Roosevelt concludes that women who choose to forgo childbearing/rearing for any reason other than natural sterility “forms one of the most unpleasant and unwholesome features of modern life.” The prosthetic womb project serves to advance affinity, enfreak motherhood, and offer an alternative to oppressive rhetoric. In its imaginary and theoretical spaces, the prosthetic womb seeks to sever the cord that binds the female body to its womb, and vice versa.

Twenty years ago, Anne Balsamo identified the female body as a “potentially ‘maternal body’ even when not pregnant…evaluated in terms of its psychological and moral status as a potential container for the embryo or fetus” (90). The fetus, Balsamo explains, has become the “primary obstetrics patient” (90), displacing the (female) body in which it is contained. Remnants of this rhetoric grip political conversations in recent years, reinforcing the need to examine the signification of the female body in contemporary discourse. Not long ago, Senator Ted Cruz (R-Texas) admonished Donald Trump and Trump’s initial suggestion to punish women in abortion cases: “We shouldn’t be talking about punishing women; we should affirm their dignity and gift to bring life into the world” (@tedcruz). Women in 2016 remain the “gifted” bearers of children, regardless of the trauma or sacrifice of childbirth. Like so many politicians before him, Cruz comfortably cradles his sexist rhetoric in the language of glory and commendation for the “work” of women’s wombs. In keeping with Balsamo’s claims of fetus celebrity, the link in Cruz’s tweet opens to a photograph of a fetus rather than the woman, confirming Barbara Duden’s claim that “‘the public image of the fetus shapes the emotional and the bodily perception of the pregnant woman’” (as cited in Balsamo 91).

In her introduction to OOF, Katherine Behar writes about “the power of carpentry, the potency of praxis” (22). I invite you to make this kit. I also invite you to remake this kit. Gestate whatever you want. Don’t impregnate the body. Remove limbs; add limbs. Introduce accessories. A small project with big ideas, the urgency of reproductive justice will be part of your makes.

Instructions

Become the mother you always never dreamed of.

To make a doll you will need:

heavy weight paper, a printer, scissors, brads, glue, wax paper

Downloadable template at http://media.hyperrhiz.io/enculturation/digbook.pdf

-

Print booklet (or just the pages you need) on some sturdy paper.

-

Using scissors or other sharp tool, cut out the pieces you’d like to assemble.

-

Attach body parts as indicated (A to A, etc.) using brads (this will make the limbs moveable).

-

Attach prosthetic womb bracket to spine with brads.

-

Sandwich fetus between sac membrane pieces (suggestion: use wax paper or other semi-transparent material).

-

Glue port to sac membrane.

-

Ignore all or some of this and make whatever you want.

Share your doll!

Twitter: @awombofonesown

email: jesschriver@gmail.com

@awombofonesown. “Made it. #enfreakwombs #makingscholarship #gradresearch @Rutgers_Camden” Twitter, 25 Apr. 2017, 3:51 p.m., https://twitter.com/awombofonesown/status/724687389977923584.

@tedcruz. “We shouldn’t be talking about punishing women; we should affirm their dignity and gift to bring life into the world tedcruz.org/news/cruz-dona . . .” 30 Mar. 2016, 5:23 p.m., https://twitter.com/tedcruz/status/715288329462407172?lang=en

Balsamo, Anne. Technologies of the Gendered Body. Duke UP, 1996.

Behar, Katherine. “Introduction.” Object Oriented Feminism. U Minnesota P, 2016.

“Bow Stands Up.” black•ish, created by Kenya Barris, performance by Tracee Ellis Ross, season 4, episode 2, ABC Studios, 2017.

"breach, v." OED Online, Oxford UP, June 2019.

Dunn, Katherine. Geek Love. Vintage Books, 1983.

Hamzelou, Jessica. “Artificial Womb Helps Premature Lamb Fetuses Grow for 4 Weeks.” News Scientist. 25 Apr. 2017. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2128851-artificial-womb-helps-premature-lamb-fetuses-grow-for-4-weeks/

Haraway, Donna. “The Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century.” The Cybercultures Reader, edited by David Bell and Barbara M. Kennedy. Routledge, 2000. 291-324.

Hayles, Katherine N. My Mother Was a Computer: Digital Subjects and Literary Texts. U of Chicago P, 2005.

Hensley Owens, Kim. Writing Childbirth: Women’s Rhetorical Agency in Labor and Online. Southern Illinois UP, 2011.

Higgonet, Anne. Pictures of Innocence: The History and Crisis of Ideal Childhood. Thames & Hudson, 1998.

JesSchriver [Jess Schriver]. “Mother May I.” Squarespace, 2017, http://jess-schriver.squarespace.com/mother-may-i/.

Martin, Emily. The Woman in the Body: A Cultural Analysis of Reproduction. Beacon, 2001.

Montagne, Renee. “To Keep Women From Dying in Childbirth, Look to California.” Weekend Edition Sunday, NPR. 29 July 2018. https://www.npr.org/2018/07/29/632702896/to-keep-women-from-dying-in-childbirth-look-to-california.

Morton, Timothy. “All Objects are Deviant: Feminism and Ecological Intimacy.” Object Oriented Feminism, edited by Katherine Behar. U Minnesota P, 2016.

Pitts, Victoria. In the Flesh. Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

Pollock, Anne. “Queering Endocrine Disruption.” Object Oriented Feminism, edited by Katherine Behar. U Minnesota P, 2016.

Roberts, Dorothy. Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty. Vintage, 1999.

Roosevelt, Theodore. “Address by President Roosevelt before the National Congress of Mothers.” National Congress of Mothers, Washington, DC. 13 Mar. 1905. https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital-Library/Record?libID=o280100.

Salam, Maya. “For Serena Williams, Childbirth Was a Harrowing Ordeal. She’s Not Alone.” The New York Times. 11 Jan. 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/11/sports/tennis/serena-williams-baby-vogue.html.

Sayre, Jillian. “Significant Otherness.” English Department, Graduate School, Rutgers University. Spring 2015. Syllabus.

Villarosa, Linda. “Why America’s Black Mothers and Babies are in a Life-or-Death Crisis.” The New York Times Magazine. 11 Apr. 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/11/magazine/black-mothers-babies-death-maternal-mortality.html.