Elliot Tetreault, The University at Albany, SUNY

(Published March 24, 2022)

In 2017, an organization called Black Fist hired martial arts instructors to teach self-defense classes to Black communities in cities across the US. As The Root reported, one instructor, Omowale Adewale of New York City, communicated with someone named Taylor only via telephone about the arrangement, which required that Adewale teach four classes per month for $320, paid over PayPal and Google Wallet (Harriot). Taylor “instructed Adewale to take pictures of black people learning martial arts” (Harriot). Similar situations happened in a few other cities, and in all cases, the situation was suspicious to local communities. Trainers never met Black Fist representatives in person, and they were all asked to take photographs (Harriot). The seeming illegitimacy of the enterprise proved true, but in a surprising way. In 2019, the case of Black Fist and the mysterious self-defense classes appeared in Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller’s Report on The Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election. The report states, “In February 2017, the persona ‘Black Fist’ (purporting to want to teach African-Americans to protect themselves when contacted by law enforcement) hired a self-defense instructor in New York to offer classes” (39). Although the Mueller Report does not mention the photographs, reporter Michael Harriot speculates, “So what would be the point of pictures of black people learning to fight? Well, it seems as if the Russians knew that playing up white people’s racial anxieties was one of the keys to helping Trump win.”

Black Fist is just one example of Russian targeting of Black Americans before, during, and after the 2016 US presidential election as part of a large disinformation campaign. It is now well known that the Russian entity known as the Information Research Agency (RU-IRA) interfered in the 2016 election. Agents created multiple Twitter accounts, often linked to a network of other social media accounts, websites, and fake media platforms. These accounts were widespread; according to the United States House of Representatives Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, there are 2,752 suspended RU-IRA Twitter accounts, which likely does not include all of them. One site of interference is the attempted co-optation of online #BlackLivesMatter discourse.

To study RU-IRA infiltration into social media posts related to #BlackLivesMatter, informatics scholars Ahmer Arif et al. compiled and analyzed a data set of around 250,000 tweets between 2015 and 2016 containing the terms BlackLivesMatter, BlueLivesMatter, or AllLivesMatter, and that included information about police shootings. Their results show that this was more than a simple disinformation campaign, but rather “an improvised performance being carried out by an account operator (or, perhaps, a small team of operators) to try and ‘inspire’ the online communities they target. These performances can involve connecting to cultural narratives that people know, enacting stereotypes, and modeling how to react to information” (2). In other words, these information agents were rhetorically savvy. They were not just publishing biased information or circulating false narratives but performing a campaign of influence that was more fluid, nuanced, and difficult to counter. The goal of such information operations is “not necessarily to convince someone of something, but to strategically direct discourse in ways that ‘kill the possibility of debate and a reality-based politics’” partly by “strategically and opportunistically tapping into latent social fractures” (3).

In the context of these complicated disinformation campaigns, rhetorical studies has renewed its commitment to understanding how disinformation spreads, and further, what the prevalence of disinformation tells us about the complexity of political rhetoric in an era characterized as “post-truth.” As Jim Ridolfo and William Hart-Davidson explain, “The militarized deployment of digital rhetoric is now part of our everyday lives—that is, the production and proliferation of mass disinformation campaigns” (4). However, studies of disinformation have often failed to contend with race and racism (Mejia et al. 110). Further, scholarly efforts to counter disinformation campaigns have often ignored how multiply marginalized groups have always had to contend with disinformation and have developed innovative strategies for doing so. As this article will detail, Black rhetorical practices have much to offer to the study of political disinformation. In addition, analyzing the specific practices that Black activist communities use to challenge disinformation can add to the body of work in rhetoric, composition, and communication studies on Black rhetorical practices more broadly.

Scholars in rhetorical studies and other fields, including Adam Banks, Carmen Kynard (“Wanted”), Ruha Benjamin, and Safiya Umoja Noble, have provided rich analyses of the many ways racism is structured into technologies and have argued for the centrality of race to the study of technology. In addition, rhetorical studies is reckoning with a history of racism, and numerous scholars have brought attention to how theories and practices in the field have inherited white supremacy. Many have asserted the centrality of race to rhetorical studies, challenging fieldwide assumptions that rhetorics of race are marginal rather than key to understanding rhetoric in general. For instance, Kynard argues for fieldwide attention to “race-radical literacies [that] read and write an unapologetically intersectional ontology, particularly in their refusal to disavow the ways that black feminisms and black queerness politicize a range of ‘racializing assemblages’” and that “constantly name the structural violence of our institutions (our local settings, colleges, nation, and our field)” (“Stayin” 524). Aja Y. Martinez uses the method of critical race theory counterstory to illuminate the pervasive racism of traditional rhetorical studies curricula that frame work by people of color as “marginal” to the rhetorical tradition, revealing how core curricula represent “the occupied space of white racialized perspectives, while the voices and stories of the racialized ‘other’ are pushed to the margins in elective courses, at best, or footnotes and asides within the core curriculum, at worst” (404). Lisa A. Flores argues for a “racial rhetorical criticism, or rhetorical criticism that is reflective about and engages the persistence of racial oppression, logics, voices, and bodies and that theorizes the very production of race as rhetorical” (5). As Paula Chakravartty et al. found in a study of major communication journals, non-White scholars are not only underrepresented and under-cited, but “non-White scholars are more likely to engage race as an analytic in our field” (261). This is not just a problem of tokenistic inclusion. When scholars of color are not included, and these scholars are the most likely to “engage race as an analytic,” this means that race is not considered a central analytic in rhetorical studies. This lack of attention to race hurts the field and damages the rigor of our analytical tools. We can see this in the study of disinformation campaigns, where the Senate reports and much media coverage foreground the fact that race—specifically, Blackness and its exploitation—was central to RU-IRA operations. However, little work in the rhetoric of disinformation campaigns thus far has centered race. Accounts of the role of anti-Blackness and Black resistance to disinformation are vital parts of what scholars Alice Marwick et al. term “critical disinformation studies.” This approach argues that “disinformation is a key way in which whiteness in the United States has been reinforced and reproduced” and “encourage[s] scholars of mis/disinformation to interrogate power differentials more broadly and race specifically when discussing disinformation” (1).

It is especially important to center race in discussions of political disinformation because the competing realities that structure American political divisions are rooted in racism. Much of the discourse surrounding disinformation acknowledges that the left and the right, in addition to other factions of American politics, are not just dealing with different ideologies but operating under different realities. Rhetoric has always addressed this idea that competing perceptions of reality underlie ideologies, not just consciously held political beliefs. What mainstream rhetorical studies has not always reconciled with is the centrality of racism to the construction of these realities. Collective self-delusion around race is, in some ways, the original American political disinformation: persistent denial that white supremacy, racism, and colonialism are at the heart of our nation.

Mainstream conversations around Russian interference have drawn attention to Russian deluding of Americans, but Russian agents just tapped into existing American delusions. These delusions have been more commonly framed in media as “divides,” but the language of divides is insufficient because it reveals an assumption that if we just bridge differences and unite with people of different ideologies, then things would get better. This is not true because competing political ideologies represent different foundational beliefs about racism and its embeddedness in American society (see Bonilla-Silva). “Bridging divides,” an idealistic vision connoting conservatives and liberals sitting down to discuss political matters, will not help because what we need is a reckoning with racism instead. The language of delusions is more precise than divides, and this precision can help rhetoricians unpack what is really happening: The main competing reality we are dealing with politically is the centrality of racism to America’s deepest principles and structures.

In this article, I argue that when studying disinformation campaigns and how to counter them, rhetoricians need to trust the relational knowledge of multiply marginalized activist communities. This call for trust goes against the grain of currently dominant approaches to countering disinformation, which often foreground the need for more trust in “facts” in the sense of (assumed) objectivity, more critical thinking, or more rhetorical savvy as it is most traditionally understood in terms of argumentation and persuasion. In truth, “privileging media literacy over questions of ideology and power, however, makes post-truth scholarship and reporting complicit with post-race politics” (Mejia et al. 110). This article focuses on a less discussed but key element of countering disinformation: the relational knowledge that is key to Black Lives Matter’s activist rhetoric. It is especially necessary to pay attention to the power of relational, embodied, experiential knowledges in light of the evidence that factual knowledge alone is often unsuccessful in countering disinformation campaigns or changing deeply entrenched political beliefs.

The following section analyzes the RU-IRA’s rhetorical strategies in targeting Black Americans and exploiting American racism, as well as how reports and media coverage frame Black Americans in relation to these disinformation campaigns. Then, I detail a theory of relational knowledge grounded in Black rhetorical practices, explaining how relational knowledge can work as an activist strategy of countering disinformation. I demonstrate this concept through an analysis of examples of Black Lives Matter activists successfully challenging disinformation through relational knowledge.

Disinformation Campaigns’ Targeting of Black Americans

In much reporting on Russian interference into the 2016 election, Black Americans are framed as the targets of disinformation, rather than as agents who were successful in fighting disinformation—even though, as this article will detail, several groups of Black activists have had success in countering disinformation in their local communities. Senate Intelligence Committee reports emphasize that Russian accounts targeted Black Americans (DiResta et al. 8, Howard et al. 16-17). Such targeting was not necessarily an effort to recruit Black Americans to a particular ideology, but just one method in an arsenal of strategies designed to foster chaos and conflict. RU-IRA agents created accounts all across the American political spectrum and used them to stage fake conflicts to stoke a sense of “polarization.” It is also worth noting that the targeting of Black Americans may actually be a method of indirectly targeting White Americans, who were the observing audience for distorted performances of Blackness. Theodore Johnson, a scholar of Black voting behavior, explains that Russian accounts may have put “black activist language out on social media in order to scare white citizens into thinking their nation was changing, and mobilize white voters in support of Trump.… black folks were not the target for that.… I’m convinced the ‘Blue Lives Matter’ crowd was the target there” (Lartey). Although the reports and media coverage often frame Black Americans as the unwitting targets of Russian disinformation, in actuality, Black Americans are among the most politically sophisticated and savvy groups in the US (Cohen; Tate). Black voters, especially Black women, were instrumental in trying to keep Trump out of the White House. Online disinformation campaigns would have highly motivated reasons to try to undermine the activism of Black communities in particular, but there is not yet enough evidence about the success of these attempts. What is known is that RU-IRA accounts targeted Black Americans, and that media coverage has taken up this fact extensively, often framing Black Americans as potential victims of disinformation.

Though it is impossible to fully determine the efficacy of RU-IRA tactics (DiResta et al. 58), it is clear that fake Russian accounts attempted to subtly manipulate people through micro-targeting and playing on emotional associations. Many Russian accounts gained an audience through micro-targeting techniques meant for advertising on social media. For example, as journalist Rachel Glaser reports for Slate, “Hundreds of ads were bought about American racism, laser-targeted to people interested in, to take a few examples, ‘Understanding racial segregation in the United States,’ and ‘Martin Luther King, Jr.’ and ‘Black is beautiful’ and the ‘African American Civil Rights Movement (1954-68)’.” Further, IRA accounts tried to infiltrate racial justice discourse by using the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter on a variety of posts. However, not all these accounts’ content was highly politicized. Part of their emotional manipulation was to draw in viewers with more innocuous content and build a base audience this way, who would then be there when the accounts posted more politicized content. This performance is also a deliberate method of making it difficult to find and shut down fraudulent accounts, because this is not exactly disinformation but instead more nuanced manipulation.

Fake accounts were savvy about how they chose to present themselves; as these researchers show, they “used cultural, linguistic, and identity markers in their Twitter profiles to align themselves with the shared values and norms of either the left- or right-leaning clusters” (Arif et. al 12), and these markers were infused across their entire profiles—from their choice of profile picture to who they followed to the phrasing of their content. Further, agents aimed to create content that would be difficult to fact-check and actually often avoided overt acts of political persuasion like presenting arguments and claims. One goal was just to share an enormous volume of content, using a tactic that Jonathan L. Bradshaw has termed “rhetorical exhaustion,” or the “active means of circulating rhetorical material to halt discourse, redirect the rhetorical trajectories of public deliberations, or demobilize publics” (2). The Russian accounts made use of textual, visual, and multimodal resources such as memes to engage in mimicry and circulate their content. At first glance, these seem to mimic the rhetoric that circulates in online social justice communities, but to someone immersed in actual radical racial justice circles, they fall short. For instance, they tend to evoke simplistic understandings of historic figures in racial justice, such as Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X. Audiences familiar with contemporary racial justice conversations would recognize these simplistic characterizations.

To counter disinformation like the above examples, a deep racial justice literacy is needed—the kind that Black activist communities have long cultivated and shared through networks of relations. The following section provides a theoretical framework for understanding relational knowledge as a strategy for countering disinformation. Then I offer an extended analysis of two cases where Black Lives Matter activists in Minneapolis and Baltimore were able to counter an instance of disinformation on a local level by mobilizing their relational knowledge. I conclude with some implications for future research in rhetorical studies on disinformation campaigns.

Relational Knowledge

Relational knowledge is a specific kind of localized activist knowledge that draws its expertise from deep community connections and movement histories, and it is also a key part of Black rhetorical traditions. This article focuses in particular on Black Lives Matter activists’ use of relational knowledge to counter disinformation. Black Lives Matter is a movement grounded in a Black queer feminist epistemology, which influences the movement’s understanding of relationality. In the field of rhetoric, Black queer feminist relational knowledge has not yet been studied extensively in relation to disinformation, but this approach has much to add to the conversation. In addition, studying how activist rhetoricians use strategies rooted in relational knowledge to challenge disinformation can add to the field’s body of work on Black rhetorical practices.

Before I move further into explicating the framework of relational knowledge, I want to acknowledge my own relations and positionality. I am a White, queer, cisgender woman who is a settler scholar, with institutional and economic privilege from my position as a tenure-track academic. I benefit from white supremacy and colonialism, and as much as I seek to use my position to enact commitments to activist praxis, I have a heightened responsibility to always be reflexive about this work. In this project, I am writing about the relational knowledge of Black activist communities, and I am aware that this could become an act of co-optation for my own benefit (in the form of accruing reputation, cultural capital, and publications toward tenure). I do not pretend to have invented or “discovered,” as a colonialist concept, the activist praxes I am writing about, but I see an opportunity to use my position to amplify them for the purposes of intervening in academic conversations where I may be listened to. I am also aware of the potential irony in this article’s framing in terms of relational knowledge and the question “Who are your people?,” as I am writing about the rhetorical practices of communities I am not part of and drawing from mediated accounts of their practices rather than embeddedness in local communities. But I want to emphasize the vital differences between efforts to intrude on or appropriate from community knowledges and attempts to work across boundaries with the goal of understanding and respectful amplification. I do not pretend to be a perfect example of this work but hope that my efforts here can be part of an ongoing dialogue.

In this context, I am not part of the communities whose practices I am analyzing, but I see my role as amplifying their practices as a way to, as Temptaous Mckoy says, “make space for the experiences and knowledge-making practices of Black people and other historically oppressed individuals” (28) in rhetorical studies’ discussions of the spread of disinformation for political gain. This is also a way to use my position to answer the call to “not rely solely on the marginalized to explain or do the sole labor of making the field more inclusive” (29). This labor must be shared across rhetorical studies to truly enact antiracism in the field. As part of that labor, I hope to amplify the practice of relational knowledge and situate it as a vital component of activist responses to disinformation campaigns.

Keith Gilyard and Adam Banks explain that much African-American rhetoric foregrounds relationality and co-creation, in contrast with the classical, Aristotelian rhetoric that is most commonly emphasized in rhetorical studies, which represents a more individualistic worldview: “Rather than emphasizing the audience participation and the co-creation of meaning that are more characteristic of African verbal culture with its prevalent call-and-response modality, the classic Aristotelian formulation suggests people independently manipulating ‘means’ to persuade others through ‘delivery’” (47-48). One example is the importance of call-and-response to African American rhetoric, a bidirectional process that challenges classical and Eurocentric models of a speaker targeting an audience and that forwards a much more relational process (47-48). Especially relevant to the rhetoric of Black Lives Matter, relational modes of interaction and experience are also key to Black feminist theory. Patricia Hill Collins writes that the four elements of a Black feminist epistemology are “lived experience as a criterion of meaning, the use of dialogue, the ethic of personal accountability, and the ethic of caring” (266), all of which foreground relational, not only individualistic, ways of being and acting in the world. Relationality is a key part of radical community activist groups (Licona and Chávez 96; Licona and Russell 2). Adela C. Licona and Karma R. Chávez posit the concept of relational literacies as “understandings and knowings in the world that are never produced singularly or in isolation but rather depend on interaction. This interdependency animates the coalitional possibilities inherent in relational literacies” (96). Scholars have also theorized relationality in terms of cross-community solidarity (Ramos; Del Hierro et al.), as well as coalition-building that foregrounds negotiations across positionalities (Carillo Rowe; Chávez). Further, relational knowledge describes not only activists’ relationships with others in the present, such as a local community, but also connections over time. Eric Darnell Pritchard describes how, in addition to relations with those in the present, relations with movement histories are vital for Black LGBTQ people (103). Relational knowledge is constituted not only by local communities and connections in the present, but also reaching across history through relations with ancestors and elders and invoking imaginative connections (Pritchard). Part of relational knowledge is also being in relation with movement histories and ideologies.

As the title of this article previews and as the following examples of BLM activists countering disinformation will further develop, the question “Who are your people?” is key to relational knowledge. Civil rights organizer Ella Baker was known for asking this question. It exemplified Baker’s approach to organizing, which emphasized community-building and the power of ordinary people to make change, rather than traditional models of top-down charismatic leadership. In radical activism with the goal of systemic change, it is imperative “to find out who we are, where we have come from and where we are going” (Baker), a process enabled by relational knowledge. Scholar Barbara Ransby details in her book Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision that “Who one’s people were was important to Ella Baker, not to establish an elite pedigree, but to locate an individual as part of a family, a community, a region, a culture, and a historical period. Baker recognized that none of us are self-made men or women [sic]; rather, we forge our identities within kinship networks, local communities, and organizations” (14). These networks, communities, and organizations, and the knowledge they sustain, are also key to a marginalized group’s ability to counter disinformation attacks.

Knowing “who are your people” also helps activist communities detect who is not being a respectful guest in the movement—an important strategy for countering disinformation attacks. A localized activist community is a “home place.” As Jacqueline Jones Royster explains:

People in the neighborhood where I grew up would say, ‘Where is their home training?’ Imbedded in the question is the idea that when you visit other people's ‘home places,’ especially when you have not been invited, you simply can not go tramping around the house like you own the place, no matter how smart you are, or how much imagination you can muster, or how much authority and entitlement outside that home you may be privileged to hold (32).

Cross-community discourse and even coalition-building are certainly possible when respect for others’ “home places” is foregrounded. However, communities are rightly suspicious of those who intrude on “home places” without the necessary respect and knowledge. The ability for community members to detect what is a good faith effort at connection and what is an intrusion is a function of relational knowledge: the knowledge that an activist community has built up communally, over time, influenced by movement histories, and with a deep sense of who each other’s people are. Disinformation actors are sometimes attempting to intrude on “home places,” as in the case of RU-IRA infiltrations into online BLM discourse, but through their well-developed relational knowledge, activists are primed to detect these intrusions.

Baker’s question of “Who are your people?,” combined with Royster’s concept of “home places,” represent a relational approach to organizing that can be seen in today’s Black Lives Matter movement, which is deliberately coalitional and non-hierarchical, rooted in localized community building rather than top-down leadership. There has been much scholarship on the rhetorical practices of BLM, but less work has been done on BLM activists’ use of relational knowledge specifically to counter disinformation. Paying attention to these strategies can reframe Black communities not as the victims of disinformation campaigns, but as innovators developing ways to resist political disinformation that are rooted in their lives and worldviews. To these ends, the following section uses two examples to illustrate relational knowledge in action. I start with an overview of how Black Lives Matter responded to reports of Russian interference. Then, I amplify how local groups of Black activists in two cities used relational knowledge to counter attempted RU-IRA co-optation of Black Lives Matter discourse online.

Black Lives Matter Activists’ Relational Knowledge

Black Lives Matter’s Movement Rhetoric

As Elaine Richardson and Alice Ragland describe, Black Lives Matter is rooted in Black literacy traditions:

Through the purposeful use of Black language, communicative practices, and new literacies, young Black people are challenging racism, police brutality, and social inequality, while fighting for effective alliances. In so doing, they are performing unapologetic Blackness, seeking to disrupt hegemonic race, gender, sexuality, class oppression, and other social inequities for the greater good of all Black lives. (52)

Black language, cultural practices, and activism are frequently co-opted by other groups as a colonialist and white supremacist process of appropriation or as a weapon of distortion. It is thus no surprise that distortion is already one of the key rhetorical weapons used to discredit Black Lives Matter. As BLM cofounders Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi, among other activists, consistently remind audiences, BLM’s messaging is frequently taken up and distorted for malicious purposes, as a larger mechanism of power to discredit the radical potential of the queer Black women’s rhetoric that started the movement.

In the official response to the Senate Intelligence Committee reports on Russian interference, Black Lives Matter stated, “The Black Lives Matter Global Network understands that it is a target as we continue to fight for Black liberation across the globe, and we will not be deterred by those attempting to exploit us and the millions of Black folks in America who vote and demand change. We will continue to work tirelessly to challenge white supremacy, injustice, and oppression throughout the world” (“Black Lives Matter Global Network Responds”). The statement goes on to reiterate the origins and mission of Black Lives Matter, foregrounding the relations that sustain the movement: “Founded in 2013 by Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi in response to the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s murderer, Black Lives Matter Global Network is a chapter-based, member-led organization in the US, UK, and Canada.” They foreground BLM’s intersectional mission—“We support the lives of the Black queer and transgender communities, the disabled, the undocumented, those with records, women, and all Black lives along the gender spectrum”—and end with its radical imagination: “By combating and countering acts of violence, creating space for Black imagination and innovation, and centering Black joy, we are winning immediate improvements in our lives.” BLM’s to-the-point response acknowledges the Senate reports but quickly pivots to highlight the actual work being done by BLM activists. They also refocus attention on systemic anti-Blackness, underlining the fact that this, not Russian interference, is the real problem.

Black Lives Matter, although an enormous movement, is characterized by its commitment to an intersectional approach and to the locally grounded, relational knowledge of Black activist communities. Activists mobilized this knowledge to counter fraudulent social media accounts that were later revealed as RU-IRA plants. I offer two examples here of activist groups in Minneapolis and Baltimore who were successful in challenging fraudulent profiles and countering disinformation because they mobilized their relational knowledge.

Minneapolis

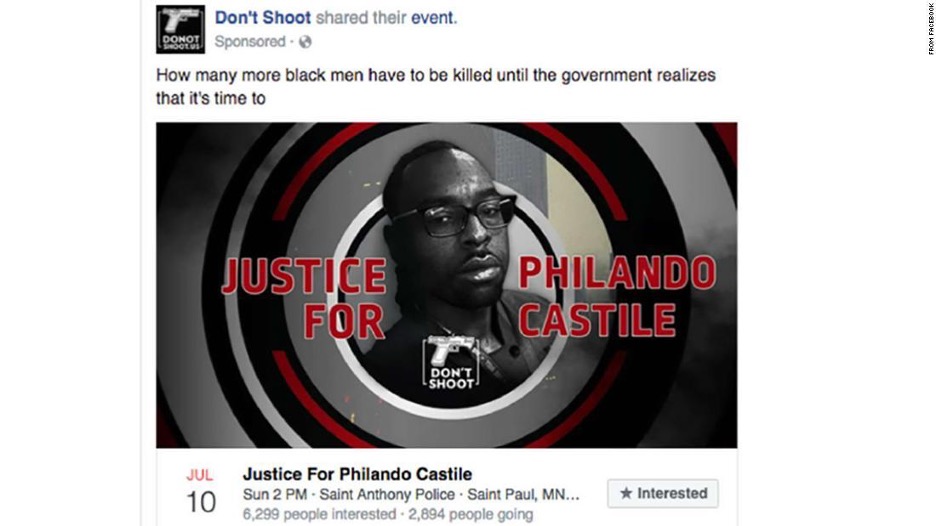

On July 7, 2017, police shot and killed 32-year-old Philando Castile in a Minneapolis suburb. Castile’s girlfriend Diamond Reynolds had been recording the police stop, and the shooting was streamed on Facebook. Only a few hours after the shooting, a Facebook page with the name “Don’t Shoot” started targeting people living near the Twin Cities and promoting an event called “Justice for Philando Castile” (see Figure 1). This page and the event were later revealed to be run by a fake Russian account (O’Sullivan).

Figure 1: Fake march in Minneapolis. Screenshot by CNN.

In media coverage of the fake event, Minneapolis Black Lives Matter leader Mica Grimm described that something felt wrong about the event because no one in the tight-knit local activist community knew who was running it. Also, the language was off; as CNN reports, Grimm thought the name “Don’t Shoot” was a strange and dated formulation. The phrase “Hands up, don’t shoot” was common after the murder of Mike Brown in Ferguson in 2014, but Grimm explains that by 2016, “many Black Lives Matter activists were no longer using the chant because they felt it was submissive and they wanted to focus on language that they felt was more empowering” (O’Sullivan). As Grimm also said during the CNN documentary on this case because no one knew the people behind Don’t Shoot, experienced activists decided “we need to reach out to these people to make sure they don’t put anyone in danger.” Another activist, Sam Tyler, contacted the Don’t Shoot page to ask who was organizing the event, and they responded by referencing the names of local groups, but the people Tyler, Grimm, and others knew who were working for these groups also did not know who was behind Don’t Shoot. Eventually, as Tyler described to CNN, “After talking to them a little bit back and forth and realizing that they were completely making up everything that they had been saying.… We decided to present them either the ultimatum of either handing us administrative access to the event page or we were going to dissuade people, through a press release, through whatever means we had, of showing up to this event” (O’Sullivan). Don’t Shoot gave in and handed control of the Facebook event to these activists. Grimm explains, “Our solution was to take over the event and have our own marshals and have our own leaders, and a lot of other organizations helped us do that. Just to make sure that if people were going to show up, that people weren’t putting themselves in a position of danger” (O’Sullivan). This example reveals that, although the Russian accounts’ use of language and other tropes may seem accurate to outsiders, to insider audiences it often rings false in subtle but important ways, pointing to the need to trust the knowledge of activists.

The Minneapolis Black Lives Matter activists used several strategies in their discussion of the Don’t Shoot event with CNN to highlight their own expertise and redirect attention back to the real matters at hand: protesting police violence and memorializing Castile. Grimm demonstrates expertise in the current activist rhetoric of Black Lives Matter by explaining the datedness of the “don’t shoot” language and pointing out how she used this as a cue for the insincerity of the account. Grimm and Tyler also establish their expertise in activist organizing when they speak about putting safeguards in place to make sure that those attending the protest would not be put in danger. In a media environment when it’s commonly represented that anyone with a digital presence can be an activist, Grimm and Tyler are drawing attention to the extensive skills and experience needed to actually accomplish meaningful community action. In the process, they refute the Don’t Shoot account through emphasizing the holes in its performance of activism, which in turn reveal Don’t Shoot’s lack of expertise.

Further, Grimm and Tyler emphasize the importance of community networks, highlighting the in-person local communities that are essential to activism and pointing out that the digital presence of Don’t Shoot is meaningless without an ability to show connections with local groups. In Unapologetic: A Black, Queer, and Feminist Mandate for Radical Movements, activist Charlene A. Carruthers draws on Ella Baker’s question “Who are your people?” to argue that the work of community organizing requires understanding who one is in relation with, which also depends on one’s positionality, and the degree to which one enacts accountability to those people (98-99; see also Ransby 14). Carruthers writes:

It is easier to support an idea than it is to be in solidarity with specific people. That takes work. One example is how people join calls for solidarity with oppressed groups without names of people or organizations being explicit. Alliance with an idea is not as powerful as real solidarity that shows up and is manifest in action. Solidarity requires more than thinking. It requires action, and it requires us to follow the leadership of those who are the most directly affected (99).

Through this lens, Tyler, Grimm, and the other activists in Minneapolis are basically asking the Don’t Shoot page, “Who are your people?” Don’t Shoot’s deflection and inability to answer serves as further evidence of inauthenticity. It attempts to declare solidarity “without names of people or organizations being explicit” (Carruthers 99). It does not “follow the leadership of those most directly affected” (Carruthers 99). When asked, Don’t Shoot cannot name its people. More than anything, this reveals the account’s fake performance of solidarity that actually stands on nothing. Grimm and Tyler recognize this not only through their experiential knowledge as long-time local activists, but also through the ways this knowledge is informed by the movement history and theory of Black Lives Matter—grounded in the Black radical, queer, and feminist tradition, the movement foregrounds consciousness of positionality and relationality and emphasizes the need to be accountable to those one is in community with.

My point here is that reading Russian interference, such as the Don’t Shoot example, through the lens of racial justice allows rhetoricians to see these dynamics. Without a racial justice literacy, guided by the theorizing of Carruthers and other Black Lives Matter activists and enacted by people like Grimm and Tyler, rhetoricians might look only at the surface features of pages like Don’t Shoot such as rhetorical appeals and how it uses text and images to reach an audience. It gets the language of Black Lives Matter wrong, such as the datedness of “don’t shoot” in this context. But on a deeper level, it gets the theory and ethos of Black Lives Matter entirely wrong. Looking at media coverage of this example like the CNN article, rhetoricians without a strong racial justice literacy might still miss the importance of Black activist expertise and community networks in this case—and in other, less covered cases like it. What was effective in stopping Don’t Shoot was not traditional fact-checking or rhetorical criticism; it was the relational knowledge of local Black Lives Matter activists, guided by movement history and theory.

Baltimore

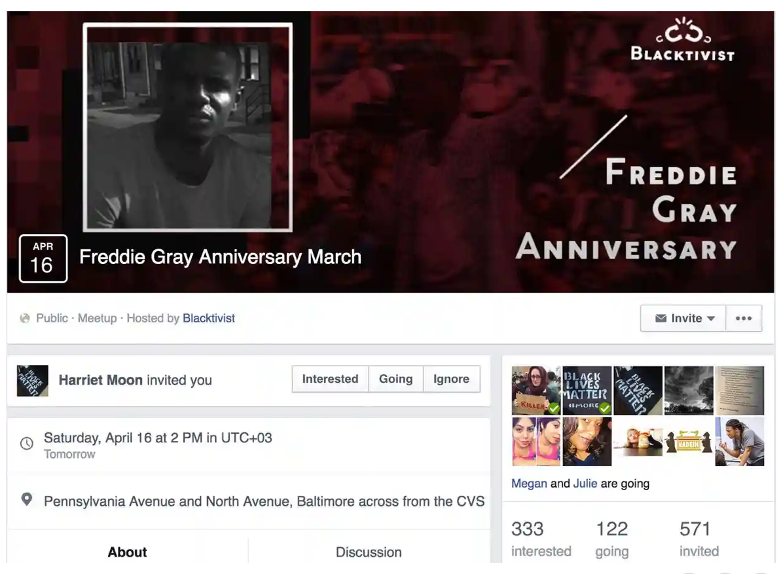

A case similar to the above example from Minneapolis happened in Baltimore in April 2016. The page Blacktivist—later revealed to be another fake IRA account—created a Facebook event for an anniversary march in honor of Freddie Gray, who was arrested by Baltimore police in 2015 with such violence that he sustained a fatal spinal cord injury. Criminal charges were filed against the police officers involved, but the charges were dropped (Lopez). Local activists in Baltimore were skeptical of the Blacktivist page claiming to be organizing an anniversary event in honor of Gray because they did not know who was behind it (see Figure 2). The Guardian reports that local pastor and community organizer Heber Brown III “thought it was an out-of-town figure trying to co-opt the local movement for publicity” and activist Jamye Wooten thought the account “could be an undercover police officer spying on protesters” (Levin). Both these activists and others knew that there was something inauthentic about the account. They assumed the motivations of the account stemmed from established patterns and histories of co-optation and surveillance, made all the more harmful because of their use of Freddie Gray’s image and story.

Figure 2: Fake anniversary march in Baltimore. Screenshot in The Guardian.

Like Sam Tyler in Minneapolis, Brown messaged the Blacktivist account on Facebook to find out who was behind it. Soon after the exchange that followed, Brown circulated a screenshot of the conversation in a public Facebook post. Brown began by asking whether the person behind Blacktivist lived in Baltimore: “I’m just hearing that you’re not from Baltimore. Is this true? Are you a local organizer/activist or not?” Blacktivist responded, “Me personally—no. But there are people in Baltimore. Volunteers. We are looking for friendship, because we are fighting for the same reasons. Actually we are open for your thoughts and offers.” Brown countered by offering a moment of activist education: “But this is not the way to organize. You should have started with the conversations before you organized an event here. The way you’re going about this is deeply offensive to those of us who are from Baltimore and have been organizing here all our lives. If you want friendship, come listen and learn before you lead.” Blacktivist then apologized and asked what they could do to make it better. Brown reiterated his points about local action: “Post a public apology. Cancel the event and take your cues from those working locally.”

In his exchange with Blacktivist, Brown highlights relational knowledge as vital for activist organizing. He starts with a variation of “Who are your people?” by asking whether the account is a local organizer or not. When Blacktivist responds with vague gestures toward “friendship” and mentions unknown “volunteers” and “people in Baltimore,” Brown immediately detects the inauthenticity and counters with, “But this is not the way to organize.” Blacktivist’s attempts to perform local connections are clearly shallow and easily detectable lies, compared with genuine activist relational knowledge. Brown highlights “start[ing] with the conversations” and advises the other account to “come listen and learn before you lead” and “take your cues from those working locally,” emphasizing the importance of relational processes like local conversations and extended periods of listening.

When he posted the screenshot of this conversation publicly on Facebook, Brown also included his commentary:

I just conversed on twitter with the “Blacktivist” person trying to organize a #FreddieGray event in #Baltimore tomorrow. Don’t have to be mean, but must be direct. You can’t bust up in somebody else’s house talking about you want friendship and are “open to our thoughts” after you take what you need. If that ain’t some settler colonialist, Euro imperial, Christopher Columbus-type occupation mentality I don’t know what is! (Let me stop before ya’ll have me cussing on Facebook.) I pray that the example of this exchange can help us do better in filtering out unsolicited “support.” (Brown)

Brown invokes activist communities as home places (Royster)—“You can’t bust up in somebody else’s house”—and connects Blacktivist’s actions with histories of appropriation of Black activism, where people from outside the local community say they want to connect but really just extract labor and knowledge without working in real solidarity with the community (“talking about you want friendship and are ‘open to our thoughts’ after you take what you need”). Brown calls out Blacktivist for participating in a pattern of colonialist extraction: “some settler colonialist, Euro imperial, Christopher Columbus-type occupation mentality” where those outside of local activist groups attempt to occupy these communities and co-opt their labor. Although Brown and his audience for the post did not know at the time that the account was a Russian fake, it was offensive enough on its own because of its rhetoric of co-optation, rooted in colonialism and white supremacy.

Brown’s refutation of Blacktivist reveals how colonialist and white supremacist logics operate in part through a valorization of individualism and a refusal of accountability, which are in direct contrast with relational knowledge. RU-IRA accounts, though they tried to pick up on Black Lives Matter rhetoric, were unsuccessful because they were operating from a rhetorical ideology totally at odds with BLM: an individualistic conception of rhetoric characterized by “people independently manipulating ‘means’ to persuade others through ‘delivery’” (Gilyard and Banks 47) rather than an approach to activist rhetoric that is grounded in embodied experience and relational knowledge—which is also impossible to fake.

Conclusion

Dominant approaches to countering political disinformation participate in a long-standing tradition of ignoring or erasing the lived, relational knowledges of multiply marginalized communities, and the activist strategies that emerge from these knowledges. In post-truth discourse, much attention has been paid to the question of “whose facts?” but not the equally vital question “whose feelings?” Whose hunches, suspicions, forms of experiential knowledge, and feelings that something is just not right get listened to? In contrast, whose feelings go unchallenged? In the US, white supremacy is a power structure with emotional weight, and disinformation campaigns—including but not limited to the RU-IRA campaign detailed here—know how to tap into this. They recognize the deep emotional investments that many Americans have in this power structure, whether or not they name it for what it is. Strategies like fact-checking are important tools when it comes to countering disinformation, but they are not enough. Forms of knowing such as activists’ relational knowledge have been overlooked in post-truth discourse, enabled partly by the common assumption that if people would just listen to facts, then the political landscape would improve. But, in the end, this is just another piece of disinformation.

Recognizing fake performances like those of the RU-IRA accounts requires much more than fact-checking the validity of an argument or representation, or even being attuned to more subtle emotional manipulation. In the case of the appropriations of activist rhetoric that I’ve covered here, a deep racial justice literacy is needed to recognize and challenge the spread of distorted performances of Blackness. Researchers in these spaces seeking to center race in the study of disinformation should listen to the work of Black activists who already knew there was something off about these accounts, often long before their authenticity was publicly called into question. One way they knew was through mobilizing their relational knowledge. By following this lead, rhetoricians can study not only the ways these fake accounts mimic racial justice rhetoric, but also tease out the subtle ways they get it wrong, and in the process amplify the communities who are doing the real work.

Arif, Amher, et al. “Acting the Part: Examining Information Operations Within #BlackLivesMatter Discourse.” Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, vol. 2, no. 20, 2018, pp. 1–27.

Baker, Ella. “The Black Woman in the Civil Rights Struggle – 1969.” Archives of Women’s Political Communication, Iowa State University. awpc.cattcenter.iastate.edu/2019/08/09/the-black-woman-in-the-civil-rights-struggle-1969/. Accessed 19 Nov. 2021.

Banks, Adam. Race, Rhetoric, and Technology: Searching for Higher Ground. Routledge, 2005.

Benjamin, Ruha. Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Polity, 2019.

Black Lives Matter. “Black Lives Matter Global Network Responds to Senate Intelligence Committee Reports.” 18 Dec. 2018. blacklivesmatter.com/pressroom/black-lives-matter-global-network-responds-to-senate-intelligence-committee-reports/. Accessed 19 Nov. 2021.

---. “Statement from Black Lives Matter Global Network on Fraudulent Social Media Accounts.” 10 Apr. 2018. blacklivesmatter.com/pressroom/statement-from-black-lives-matter-global-network-on-fraudulent-social-media-accounts/. Accessed 19 Nov. 2021.

Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America. Rowman & Littlefield, 2017.

Bradshaw, Jonathan L. “Rhetorical Exhaustion & the Ethics of Amplification.” Computers and Composition, vol. 56, June 2020.

Brown, Heber III. Facebook post. 15 April 2016. www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10154097683603610&set=a.423996223609&type=3&theater. Accessed 19 Nov. 2021.

Carillo Rowe, Aimee. Power Lines: On the Subject of Feminist Alliances. Duke UP, 2008.

Carruthers, Charlene A. Unapologetic: A Black, Queer, and Feminist Mandate for Radical Movements. Beacon Press, 2018.

Chakravartty, Paula, et al. “#CommunicationSoWhite.” Journal of Communication, vol. 68, no. 2, 2018, pp. 254–266.

Chávez, Karma R. Queer Migration Politics: Activist Rhetoric and Coalitional Possibilities. U of Illinois P, 2013.

Cohen, Cathy. Democracy Remixed: Black Youth and the Future of American Politics. Oxford UP, 2010.

Collins, Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Routledge, 2000.

Del Hierro, Victor, et al. “We Are Here: Negotiating Difference and Alliance in Spaces of Cultural Rhetorics.” enculturation, vol. 21, 2016.

DiResta, Renee, et al. The Tactics and Tropes of the Internet Research Agency. New Knowledge, 2019.

Flores, Lisa A. “Toward an Insistent and Transformative Racial Rhetorical Criticism.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, vol. 15, no. 4, 2018, pp. 349–57.

Glaser, April. “Russian Trolls Were Obsessed With Black Lives Matter.” Slate, 11 May 2018. slate.com/technology/2018/05/russian-trolls-are-obsessed-with-black-lives-matter.html#annotations:cGyIfDBsEem5lINqxGCNlA. Accessed 26 Feb. 2019.

Gilyard, Keith, and Adam Banks. On African-American Rhetoric. Routledge, 2018.

Harriot, Michael. “Mueller Report Reveals How Black Activists, White Tears and Racism Helped Trump Become President.” The Root, 19 Apr. 2019. www.theroot.com/mueller-report-reveals-how-black-activists-white-tears-1834150537. Accessed 27 Nov. 2019.

Howard, Philip N., et al. The IRA, Social Media and Political Polarization in the United States, 2012-2018. U of Oxford, 2019.

Kynard, Carmen. “Stayin Woke: Race-Radical Literacies in the Makings of a Higher Education.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 69, no. 3, 2018, pp. 519–528.

---. “‘Wanted: Some Black Long Distance [Writers]’: Blackboard Flava-Flavin and Other Afro-Digitized Experiences in the Classroom.” Computers and Composition, vol. 24, issue 3, 2007, pp. 329-345.

Lartey, James. “Race and Russian Interference: Senate Reports Detail Age-old Tactic.” The Guardian, 24 Dec. 2018. www.theguardian.com/world/2018/dec/24/race-russian-election-interference-senate-reports. Accessed 29 Nov. 2021.

Levin, Sam. “Did Russia fake black activism on Facebook to sow division in the US?” The Guardian, 30 Sept. 2017. www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/sep/30/blacktivist-facebook-account-russia-us-election. Accessed 29 Nov. 2021.

Licona, Adela C., and Karma R. Chávez. “Relational Literacies and Their Coalitional Possibilities.” Peitho, vol. 18, no. 1, 2015, pp. 96–107.

---, and Stephen T. Russell. “Transdisciplinary and Community Literacies: Shifting Discourses and Practices through New Paradigms of Public Scholarship and Action-Oriented Research.” Community Literacy Journal, vol 8, no. 1, 2013, pp. 1–7.

Lopez, German. “Freddie Gray Died in Baltimore Police Custody. The Justice System Will Punish No One for It.” Vox, 27 July 2016. www.vox.com/2016/7/27/12296670/freddie-gray-baltimore-police-trial. Accessed 29 Nov. 2021.

Martinez, Aja Y. “Core-Coursing Counterstory: On Master Narrative Histories of Rhetorical Studies Curricula.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 38, no. 4, 2019, pp. 402–416.

Marwick, Alice, et al. “Critical Disinformation Studies: A Syllabus.” Center for Information, Technology, and Public Life, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2021. citap.unc.edu/critical-disinfo. Accessed 29 Nov. 2021.

Mckoy, Temptaous. Y’All Call It Technical and Professional Communication, We Call It #ForTheCulture: The Use of Amplification Rhetorics in Black Communities and Their Implications for Technical and Professional Communication Studies. Dissertation, East Carolina U, 2019.

Mejia, Robert, et al. “White Lies: A Racial History of the (Post) Truth.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, vol. 15, no. 2, 2018, pp. 109–126.

Mueller, Robert S. Report on The Investigation into Russian Interference in The 2016 Presidential Election. United States, Department of Justice, Mar. 2019. www.justice.gov/storage/report.pdf.

Noble, Safiya Umoja. Algorithms of Oppression. NYU P, 2018.

O’Sullivan, Donie. “Her Son Was Killed—Then Came the Russian Trolls.” CNN, 29 June 2018. www.cnn.com/2018/06/26/us/russian-trolls-exploit-philando-castiles-death/index.html#annotations:YGP3UjByEem8n1O9Nh-7FA. Accessed 26 Feb. 2019.

Pritchard, Eric Darnell. Fashioning Lives: Black Queers and the Politics of Literacy. Southern Illinois UP, 2016.

Ramos, Santos F. “Building a Culture of Solidarity: Racial Discourse, Black Lives Matter, and Indigenous Social Justice.” enculturation, vol. 21, 2016.

Ransby, Barbara. Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision. U of North Carolina P, 2005.

Richardson, Elaine, and Alice Ragland. “#StayWoke: The Language and Literacies of the #BlackLivesMatter Movement.” Community Literacy Journal, vol. 12, no. 2, 2018, pp. 27–56.

Ridolfo, Jim, and William Hart-Davidson. Rhet Ops: Rhetoric and Information Warfare. U of Pittsburgh P, 2019.

Royster, Jacqueline Jones. “When the First Voice You Hear Is Not Your Own.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 47, no. 1, 1996, pp. 29–40.

Tate, Katherine. From Protest to Politics: The New Black Voters in American Elections. Harvard UP, 1998.

United States House Of Representatives Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence. “Exposing Russia’s Effort to Sow Discord Online: The Internet Research Agency and Advertisements.” 14 February 2019. intelligence.house.gov/social-media-content/default.aspx. Accessed 29 Nov. 2021.