Maggie Fernandes, Virginia Tech

Matthew Homer, Virginia Tech

Jennifer Sano-Franchini, West Virginia University

(Published March 24, 2022)

Over at least the last decade, both academic scholarship and popular media discussions about social media have been rightly concerned with how digital platforms reinforce and perpetuate systemic racism and inequality, largely through an attention to how racist content is distributed through biased algorithms (Noble; Benjamin; Eubanks; O’Neill; Wachter-Boettcher; Coded Bias). However, following Chun’s Updating to Remain the Same, Stark’s “Empires of Feeling: Social Media and Emotive Politics,” and Sano-Franchini’s “Designing Outrage, Programming Discord,” among others, we argue for more attention to mundane aspects of user experience, including how subtle everyday interactions on social media accumulate affectively over time. As Chun explained, “habit, with all its contradictions, is central to grasping the paradoxes of new media: its enduring ephemerality, its visible invisibility, its exposing empowerment, its networked individuation, and its obsolescent ubiquity” (15). To think through these paradoxes, this essay considers how social media platforms prime users to accept particular kinds of information as truth through affective means when said users are taking part in what is often seen as passive activity, such as browsing. We consider this question in relation to what Ahmed refers to as “stickiness,” a term she uses to “track how emotions circulate between bodies, examining how they ‘stick’ as well as move” (10). Ahmed’s concept of stickiness compels us to ask, how does Facebook “become sticky, or saturated with affect, as [a] site of personal and social tension” (11)? How do feelings stick and flow between users and the interface, and what can observing these movements teach us about how “post-truth” rhetorics circulate online? What sticks when social media users engage in passive participation such as browsing a social media feed and what are the sociopolitical consequences of such stickiness? These questions, for us, speak to affect theorist Ngai’s point that, while Hobbes and Machiavelli “made fear central to their theories of modern sovereignty and the state,” late capitalism runs on ambivalent “sentiments of disenchantment” such as envy, paranoia, irritation, and anxiety—feelings that ironically “once marked radical alienation from the system of wage labor” (3-5), as well as Chun’s point that “the proliferation of crises have been so central to neoliberalism, as proselytized by Milton Friedman and as criticized by Naomi Klein” (85). In other words, the development, maintenance, and reproduction of contemporary political economies are fundamentally contingent on the rhetorical manipulation of affect and emotion. Furthermore, Ngai notes that this affective “ambivalence [is] demonstrated by the fact that all are mobilized as easily by the political right as by the left” (5). Put differently, the ambivalent sensibilities so often associated with passive social media use are instrumentalized by those across political parties in the service of corporate capitalism.

Along these lines, we argue that any attempt to study what it means to do rhetoric in the post-truth age requires attention to the critical relationship between emotion, affect, and social media. Consider, for instance, the critical role of affect manipulation in Russian efforts to sow political discord through disinformation during the 2016 U.S. presidential campaigns. Consider, too, how terms such as lurking, creeping, doomscrolling, FOMO (fear of missing out), and “feeling attacked” or “seen” are ways of talking about mediated affectations, reflecting our emotional relationships with social media. Recent scholarship in media studies has demonstrated how, at least in the case of Facebook, the manipulation, quantification, and processing of user emotions plays a key role in its business strategy (Bakir and McStay; Stark “Empires”). For instance, in “Empires of Feeling: Social Media and Emotive Politics,” Stark argued that Facebook and other social media platforms track “users’ emotive expressions as part of a broader effort to collect behavioral and psychological data in the service of commodifying attention,” and that it does so in ways that “betray patriarchal, cisgender-normative and neocolonial anxieties about the status of emotions as a force for change” (299). One example of how this tracking happens is through “algorithmic psychometrics” via Facebook’s “reactions” function, where users are able to “react” to posts through seven emotion-based responses: like, love, care, wow, haha, sad, and angry (Stark “Algorithmic”; Sano-Franchini). In addition, Bakir and McStay pointed out that “fake news exploits the ‘economics of emotion,’ where sensationalist content that also accords with the user’s preconceived ideas acts as clickbait” (267). Perhaps more significantly, “the potency of emotions in mobilizing and bonding people into shared structures of feeling and common causes unfortunately means that they are also utilized in disinformation campaigns, as propagandists seek to spread deceptive and manipulative messages” (Bakir and McStay 269). But how does this mobilization of feeling work on a granular level, from one use to another? This article seeks to address this question.

To investigate the micro-level affective attachments that occur in the context of passive Facebook use, we developed what we refer to as an affective time use study, a method described in greater detail below that we believe would be a useful addition to existing strategies for studying user experience.[1] We three researchers also served as participants in the affective time use study described in this essay. To briefly overview our findings, the study demonstrated how we are differently oriented toward various information, whether as contingent on place, gender, and professional relationships and activities. In addition, although we encountered and reacted to different kinds of political content during the week of the study, all three of us recorded several instances of unintentional interactions, such as opening the app or clicking a link without consciously thinking to do so. Facebook provides a sensibility of closeness despite physical distance. In doing so, Facebook reorients our spatial relationships with people, with our digital lives, and with the site itself. Finally, we each expressed several moments of ambivalence related to our Facebook use; for instance, feeling that it is compulsory but stressful. Ultimately, this essay argues that 1) the concept of sneaky rhetorics, or the sensibility of mistrust that is part and parcel of social media use in current times, provides a way of understanding how everyday behaviors such as browsing on Facebook contribute to misinformation online, distracting social media users in ways that uphold dominant ideologies and benefit media corporations; and 2) our method of affective time use study offers a way of understanding the affective implications of social media use. We conclude with a brief discussion of limitations and future studies in this area. In the section that follows, we overview some existing scholarship on the relationship between affect and social media use.

Digital Rhetoric, Affect, and Social Media

Recent scholarship within the field of digital rhetoric has discussed the sociopolitical consequences of feelings and affect on social media (Lotier; Nelson; Sparby; Reyman and Sparby). For example, in “Complex Rhetorical Contagion: A Case Study of Mass Hysteria,” Nelson examined the affective impact of viral content, writing that “affective networks shape our moods, foster conditions for virality, and drive us to transmit contagions.” Via the metaphor of contagion, Nelson pointed to the ways social media facilitates the transmission of viral ideas, feelings, and behaviors in intentional and unintentional ways that still require further examination. With greater attention to the sociopolitical consequences of such contagions, work in the collection Digital Ethics: Rhetoric and Responsibility in Online Aggression (Reyman and Sparby) explored the affective conditions of social media that foster widespread abuse, conflict, and harassment, considering in particular the affective experiences facing women, people of color, LGBTQ+ people, and other marginalized groups online (Dieterle et al.; Gelms; Gruwell). Similarly, in “Reading Mean Comments to Subvert Gendered Hate on YouTube: Toward a Spectrum of Digital Aggression Response,” Sparby examined the impact of gender-, race-, sexuality-, and disability-based aggression on YouTube creators, explaining that “‘mean comments’ have the power to shape reality, shift identities, and alter agency by discouraging and excluding certain voices.” By underscoring the affective experiences of online aggression as key to online culture, Sparby’s work suggests a continued need to pay attention to how affect structures experiences online. In this way, Sparby’s work evidences the stickiness, to use Ahmed’s concept, of social media environments. Just as mean comments stick to social media environments with important ramifications, we suggest that not only exceptional content but also the everyday, affective experience of navigating digital interfaces similarly sticks online, in ways that can make users susceptible to mis/disinformation.

To study the sociopolitical consequences of social media's affects, we build on the wealth of scholarship about how passive Facebook use affects users’ well-being. For example, Verduyn et al. found that passive Facebook use “undermines affective well-being” through a causal relationship between passive use, envy, and depression (480). Looking at the affective impact of the fear of missing out (FOMO), Rozgonjuk et al. argued that passive use of Facebook leads to habits of social comparison and “is associated with a range of negative outcomes, including social anxiety, loneliness, jealousy, and depressed mood” (1). It is important to consider negative affective impacts of passive use like browsing alongside the documented impacts of habitual use on users’ well-being. Dhir et al. linked compulsive social media use to social media fatigue, a mental state characterized by exhaustion from information and connection overloads and linked to elevated risks of anxiety and depression. Similarly, Elhai et al. associated compulsive social media use with rumination, or the obsessive attention to one’s negative thoughts, and Dempsey et al. characterized habitual social media checking as a maladaptive behavior to relieve or satisfy rumination about social/interpersonal relationships (5). Our work extends the findings of these studies by offering insights into the first hand, subjective, and affective experiences of browsing and Facebook use, analyzed from a rhetorical perspective and with implications for disinformation online.

“Lurking” is a term that is often used to speak to the affective experience of passive participation on social media, and thus, we would argue, a way of understanding how social media affects stick. Lurking is typically understood as a way of browsing social media that is characterized by the predominance of browsing content shared by other users without public contributions; however, we suggest that lurking is not just an activity but perhaps more importantly an affective disposition and way of engaging social media that also speaks to what we refer to as sneaky rhetorics—a sense that there is something going on that is not completely transparent and that elicits feelings of fear, risk, and mistrust as a result of unknown audiences (for those who post content on social media) and unknown consequences (for lurkers who are themselves reluctant to post). Indeed, scholarship on lurking has examined users’ reasons for remaining concealed on social media and considered the role of emotions and feelings in these habits (Chen and Chang; Lee et al.; Preece et al.; Osatuyi). For example, both Lee et al. and Preece et al. found in their studies of lurkers in online communities that feelings such as shyness and inadequacy prevented users from contributing to online discussions, even as they participated actively in other ways, particularly through active habits of learning and information consumption. On the other hand, Osatyui connected lurking to user concerns about privacy, finding that as users’ computer anxiety increased, their tendency to lurk increased, and vice versa. Finally, doomscrolling has been identified in recent years as a kind of lurking characterized by the obsessive reading through negative news on social media, oftentimes as a way to mitigate anxiety during moments of tragedy and uncertainty (Anand et al.; Price et al.). Current conditions are ripe for doomscrolling, particularly in terms of social media’s reliance on the attention economy and the related tendency for media companies to churn out articles and thus more and more content after any crisis—or perhaps, more accurately, to create crises.

Affective Time Use Methods

To examine the affective impacts of Facebook and to gain a sense of how Facebook primes users to respond to and/or receive information in particular ways, we developed a method that we refer to as affective time use study. That is, we adapted the method of time use diaries to focus on emotion, affect, and reflections on embodied subjectivity. Time use diaries are self-administered questionnaires used to record activities in real time, and they are one method by which scholars in technical communication, writing studies, and communication design have studied on-the-ground writing and professionalization practices (Cohen et al; Leon and Pigg), tracked literate activity online (Buck), and “describ[ed] communication strategies and practices in situ” (Lauren 67). This particular method provided us with a way to record our experiences with Facebook in real time. As Hart-Davidson suggested, time use diaries offer a way of accessing situated, contextual, and “plausible accounts of lived experience” (165). One of the advantages of time use diaries is that they “minimize the delay between the event and the time it is recorded” (Krishnamurty 198), allowing us to immediately and more accurately record our affective responses to our interactions on Facebook. As a result, we suggest that affective time use studies, with its attention to affect, emotion, and embodied subjectivity, can offer a way of accessing and becoming more mindful of how technology designs affect us.

Because we wanted to attend to how our subjective positionalities might influence our affective experiences during the study, our affective time use method incorporates several reflection moments. We began with a pre-study reflection, which involved each of us writing around 500 words about our current feelings and associations with Facebook. As we did so, we considered how we tended to use Facebook and what feelings we associated with the platform. The purpose of this activity was additionally to record in writing our pre-study associations so that we might be able to compare them with our post-study findings. Then, we spent the same single week—Sunday, November 17 to Saturday, November 23, 2019—documenting all of our interactions with Facebook, including any interactions that took place external to the site—for instance, if it came up in conversation, or through the news or other media. We chose to conduct the study this week because the fifth Democratic presidential debate would be taking place that week, on November 20, and we thought it would be interesting to study how we experienced Facebook amidst the debate and other corresponding or concurrent events.

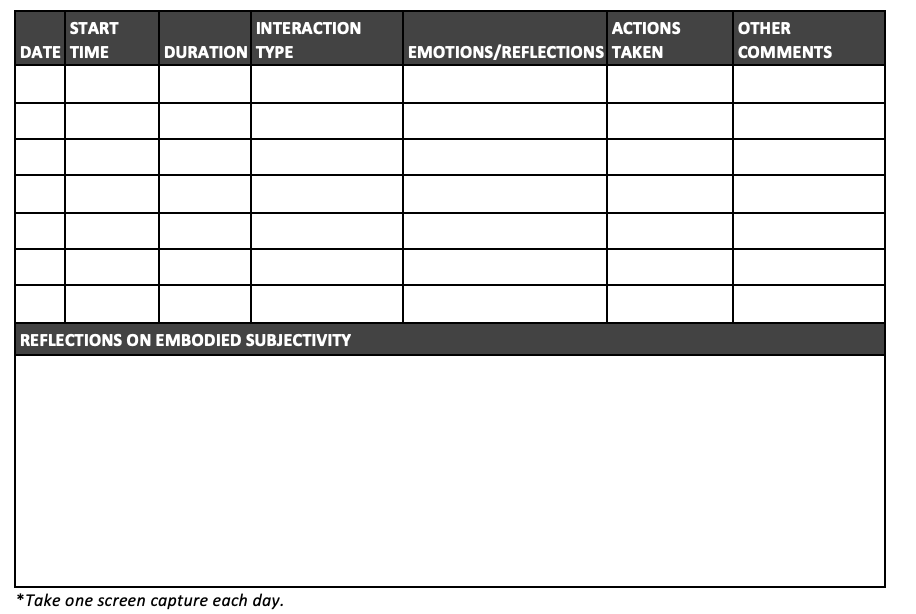

To collect our data during the week, we used structured journaling (see Figure 1). Specifically, for each interaction, we recorded the date, time, duration, interaction type, any emotions or feelings we were experiencing through that interaction, and whether the interaction prompted us toward another action, whether to click a link, check the credibility of a source, message a friend, or something else. We recorded the time we started using Facebook as well as the duration of our activities so that we could tie our affective responses to specific time uses. To identify interaction types, we drew on Sano-Franchini’s framework of four microinteractions—browsing, reacting, commenting, and posting—while supplementing this list with other possibilities: using Stories or the Messenger application, joining a group, RSVPing to an event, Facestalking (browsing specific user profiles), etc. By recording the interaction type, we would be able to link our affective responses to specific actions in Facebook’s user interface. We also included a space for any additional comments, where we would, for instance, be able to note any outside factors that might have influenced our feelings on the site, such as external stressors or lack of sleep. We entered our entries by hand, as we believed it would be easier to do while using our electronic devices to access Facebook. In addition, handwritten notes would encourage us to more slowly and deliberately reflect on our affective experiences with the site. We agreed in advance that we wanted to be attentive to any moments where we suspected dis-/misinformation taking place. Yet, rather than pre-identifying emotions or experiences to document in advance, we opted to have a conversation comparing our discourses and epistemological frameworks after data collection. This way we would be able to consider the different ways we conceptualized feelings on Facebook coming into the project.

Figure 1: Research Instrument

At the end of each day, we each wrote a short reflection of how our embodied subjectivities—whether as related to racialized, ethnic, gendered, classed, and other embodied factors—may have informed our experiences with and feelings on the site. For instance, Jennifer at times wrote about their experiences of the site as an Asian American woman, as a parent of a young child, and as an academic, while Maggie, a white woman, wrote about her experiences encountering difficult material on sexual assault and harassment, and Matt, a white settler, considered how Facebook positioned his relation to his home. Each day, we agreed to take at least one screen capture, whenever we felt compelled to do so. We agreed to try and use the site as we would normally use it, while also documenting any hesitations to interact in ways we might have otherwise because we are documenting our use. After one full day of data collection, we met on Monday, November 18 to discuss whether we wanted to make any adjustments to our methods. We then decided that we wanted to add to our data collection any actions taken as a result of the interaction. After the week of data collection, we each wrote a 500-word post-study reflection, as guided by the following prompts: Why do you stay on Facebook? What does Facebook do to encourage you to keep using its services? We met on November 26 to discuss our notes and data. We outline these methods in detail because we believe others may adapt these methods for future studies of affective experience on social media.

In addition, we consider it important to note that for this iteration of the study, we opted to take on the role of participants. This was in part because we were developing and testing out a new method for studying the affective effects of a social media platform. That is, by designing the methods and then trying them out ourselves, we would have firsthand experience with whether the methods yielded the kinds of information we were looking for, and we were able to adjust our methods as the study progressed. In addition, we believed that by purposefully reflecting upon and closely attending to our experiences as researchers and as digital and cultural rhetoricians, we would be able to think in depth about our intimate experiences with the application and thus glean more detailed results than might have been possible otherwise. As a result, this approach served as a way of studying phenomenological experiences of algorithms. Our analysis is also informed by our past experiences on social media platforms and more specifically by our combined 43 years of experience on Facebook. As in the feminist rhetorical tradition—as well as in line with contemporary affect theorists—we understand that the personal is political, and that our individual subjective affects are fundamentally socially significant (Ngai 5). Indeed, our findings are based on the first hand, subjective experiences of three individuals over the span of a single week in November 2019 and given that Facebook personalizes News Feeds to the individual, our experiences are not meant to be presented as universal nor our findings comprehensive; at the same time, we maintain that this study constitutes an effective way of gaining some understanding of how social media sticks through a focus on the nuanced, micro-level, embodied affects we discussed above.

Results

As longtime Facebook users, all three of us perhaps unsurprisingly identified Facebook as a source of anxiety and stress, feelings that we recall really starting from the aftermath of the 2016 U.S. presidential election. In their post-study reflection, Matt stated, “2016 is such a trauma for most people in my immediate circle, and Facebook plays a huge part in that trauma.” Witnessing the emotional fallout of the election and experiencing interpersonal conflicts related to politics on Facebook have contributed to our negative feelings about the site, and in turn, an increasing reluctance to post content, as we find ourselves opting instead to engage in more passive use of the site. Maggie noted a similar change to her Facebook News Feed in the years after 2016: “I think my Facebook was probably a sort of echo chamber before the election, but now it seems that most everybody I am friends with has taken their political dialogue elsewhere.” Despite this shift, she reflected, “I know that now I am more careful about what type of political content I share on Facebook,” indicating her reluctance to post as a result of anxiety about receiving combative or difficult responses. Maggie also identified the proliferation of content about sexual assault and harassment during the #MeToo movement as another cause for their move away from more active engagement on Facebook. During that time, Maggie’s doomscrolling around #MeToo topics led to her feeling overwhelmed not only with constant feelings of anger and grief from witnessing so many people, friends and strangers alike, share their traumas but also by the pressure to personally engage these difficult conversations. As a result of our increasingly negative feelings about—and associations with—Facebook, all three of us pointed to Twitter as our social media site of choice for political posting and sharing while browsing has become our primary mode of engagement on Facebook.

Although we scheduled our study to coincide with the 2019 fifth Democratic presidential debate in order to observe our emotional experience of Facebook during a publicly broadcasted political event, we did not yield any data related to this event. In our post-study discussion, Jennifer explained that although they meant to watch the debate, they did not end up doing so because of other pressing matters. Yet, this is not to say that we did not each experience political content on Facebook during the time of our study; each of us recorded interactions with posts related to different political contexts. For instance, the week of our study coincided with reports of racist and antisemitic threats at Syracuse University, including incidents that targeted Genevieve García de Müeller, a scholar in our field. Jennifer witnessed responses to the inaction of the university on her timeline. Matt experienced friends’ posts regarding protests in Hawai‘i of the construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope on Mauna Kea. For Maggie, the Facebook Memories function recalled posts from two years prior during the height of the #MeToo movement. These are three examples representing significant political events that we experienced through the News Feed during the week of the study. They do not account for all of the political content we experienced on Facebook during the study. At the same time, they do demonstrate how we are differently oriented toward different kinds of political information as individuals, whether as contingent on place, gender, professional relationships and activities, or something else that informs our political commitments, how we access information, and how we sensorially experience Facebook.

Although our experiences inevitably differed on the basis of our embodied subjectivities as well as other factors, a shared experience that all three of us noted was several instances of compulsory, unintentional interactions. The most common unintentional interaction that all three of us participated in was the mindless habit of opening Facebook to browse the News Feed and check notifications without consciously meaning to do so. For example, Jennifer wrote, “opened app without thinking,” followed by, a few hours later, “accidentally opened app” and “annoyed!”. Maggie often noticed she reached for her phone to open Facebook or Twitter upon waking up or in between activities during the day. Through this study, each of us became more aware of how frequently we open Facebook compulsively, usually noticing the habit after we realized we needed to record the interaction. Upon reflection, we noticed that we compulsively interacted with Facebook in habitual ways; for instance, we were prone to engaging Facebook upon first waking while still groggy in bed, in periods of waiting between activities, or during other moments of boredom or inactivity. In these moments, we opened Facebook and began to scroll out of habit or impulse in contrast to active decisions to seek out content or engage friends. Furthermore, we found that our compulsive tendency to open Facebook at times led to other unintentional interactions in the context of our browsing, such as, at one instance, mindlessly interacting with sponsored content despite data and privacy concerns.

What is the affective impact of this habitual, often compulsory relationship with Facebook? On reflection, we noted experiencing affective ambivalence related to our Facebook usage in several ways. During the affective time use study, we recorded feeling annoyed or confused but curious and interested, embarrassed (i.e., “got the lil buzz but then felt petty to care”) but nostalgic, anxious and self-loathing while also feeling a desire for engagement—for instance, anxiety about having a hundred tabs open on our smartphones, many of which we clicked on from Facebook, while also wanting to read and engage with the content on those tabs. In her post-study reflection, Maggie described Facebook as providing her with “little mood boosts” throughout the day, not as a result of positive interactions with friends or family but from “the near-constant stream of activity” and information. Even when engaging content that was upsetting or stressful, she found that she was on alert for information, especially content she could discuss via Messenger or text with friends. Despite this, Maggie logged feelings each day of the study that Facebook was “boring and a waste of time.” Likewise, Jennifer commented that they “feel like it’s dangerous, a waste of time, but sort of addictive or at least compulsory. It’s sometimes (maybe like 50% of the time) annoying and stressful but in mostly minor ways.” We interpret these comments as indicative of how routine behaviors on Facebook and repeated experiences of minor annoyances accumulate and stick until we generally perceive Facebook as a waste of time, annoying, and stressful. Simultaneously, Facebook usage sustains feelings of annoyance and intrigue for us, in addition to feelings of guilt, which often emerge as a result of the feeling that time spent on Facebook would be better spent doing something else.

Over time, these negative feelings led to our having negative associations with the site, which affected the felt atmosphere or climate we experienced while on the site. Our lurking habits are connected with these feelings. For example, we noticed that our feelings that posts and behaviors are subject to silent judgment by other people made posting, interacting, and sharing on Facebook stressful. At the same time, Jennifer and Maggie found themselves participating, intentionally and unintentionally, in the judgmental culture of Facebook. Maggie, specifically, noted that she often lurked on Facebook “friends” whose daily posts she found annoying or troubling in various ways, visiting their profiles unprompted by Facebook or after encountering their posts on her News Feed. In reflection, she struggled to explain the exact motivation for seeking out negative information on purpose, but she could identify through the study that the habit worsened her mood. On the other hand, browsing or lurking on Facebook can be stressful when one encounters certain information about people within their network, whether family or colleagues. For instance, it can be deeply distressing when someone within one’s network posts thoughts with which one is deeply politically opposed, particularly sentiments that are dehumanizing to themselves or others.

Relatedly, Maggie and Jennifer both noted instances of using Facebook Messenger to discuss content they encountered while browsing the News Feed. At one instance, Maggie messaged a friend to vent about something troubling posted by a mutual acquaintance after encountering it on her News Feed. This choice represented a less emotionally taxing option than directly engaging the original poster, who Maggie found difficult to engage. Similarly, Jennifer wrote about how browsing led them to use Messenger to work with a colleague to respond to the #NotAgainSU efforts, which were taking place in response to acts of racism and antisemitism at Syracuse University. In these instances, lurking manifested as a behind-the-scenes engagement with political content rather than a tendency toward public or semi-public (depending on one’s privacy settings) exchange. Especially during frustrating political discourse, lurking can function as a low-stakes form of engagement while on Facebook. In this way, this type of engagement may not be described as disinterested or passive, even as it tends to avoid direct, public, or semi-public confrontation or communication on Facebook itself. Instead, backchanneling is one way we try to remain involved on Facebook without being publicly involved on the platform.

In our post-project reflection and discussion, we asked ourselves the following question: Why stay on Facebook? Matt positioned Facebook as a kind of online “home base,” and explained he would go to Facebook first whenever he went online before any other online activity, and that having that home base creates a feeling of situatedness and stability. Similarly, Maggie and Jennifer recorded using Facebook or Facebook Messenger to keep in touch with people who they are unable to encounter otherwise in their everyday lives. For instance, Maggie wrote about how using Messenger “helps them to feel close to [people] despite distances.” In this instance, messaging via Facebook became a routine part of social media use with Facebook offering a sense of regularity to communication that they felt was somehow different than texting. Matt, too, recorded using Facebook to foster a sense of closeness with friends, specifically by encountering and liking photos and memories via the News Feed. These interactions seemed to instill in us an emotional attachment to Facebook, one the company relies on to maintain its user base, despite our negative associations and affective experiences of the platform (Mak).

Discussion

In sum, our study yielded several findings: 1) at the start of our affective time use study, we already associated Facebook with feelings of anxiety and stress; 2) in addition and not surprisingly, we observed how we were differently oriented toward different kinds of political information as individuals, whether as contingent on place, gender, professional relationships and activities, or other factors that inform our political commitments, how we access information, and how we sensorially experience Facebook; 3) we all engaged in compulsory, unintentional interactions that led to feelings of annoyance and for at least one of us, self-loathing; 4) we found ourselves noting many instances of affective ambivalence related to our Facebook usage: we were annoyed but curious, embarrassed but nostalgic, and anxious while desiring engagement, and we experienced Facebook as compulsory but stressful, and boring and a waste of time but addictive; and finally, 5) we discussed our affective experiences of intentional yet still mundane activities such as lurking, messaging, and backchanneling, and how they functioned as sources of connectivity and closeness, but also stress. Across these findings, what emerges is what we refer to as “sneaky rhetorics,” a vibe of mistrust that underlies a great deal of social media use, cultivated through online habits that are facilitated by digital interfaces and that fuels misinformation. More specifically, we understand sneaky rhetorics as a habitual feeling or even culture of mistrust that emerges through the coming together of online practices and dispositions such as lurking, creeping, and backchanneling as they take place within and among a larger media network that includes news media, popular culture, and other sources. Furthermore, sneaky rhetorics affect users across political allegiances, as it includes mistrust of the government and of colleges and universities, as well as of “alt-right” groups, bots, and trolls, and it contributes to users’ susceptibility to misinformation.

Sneaky rhetorics—the feeling that one is either being sneaky or snuck up on—contribute to feelings of fear, risk, and stress, sensibilities that we associate with Facebook, as described in our findings. These associations become embodied through practices such as lurking, particularly when combined with backchanneling, as well as vaguebooking—practices that are facilitated by the user interface and that contribute to Facebook being perceived as a place of silent judgment of other users’ posts and behaviors. Lurking is generally understood as a way that a majority of users engage online, as illustrated by what has been referred to by Nielsen as the 90-9-1 rule, or the notion that “in most online communities, 90% of users are lurkers who never contribute, 9% of users contribute a little, and 1% of users account for almost all the action.” The 90-9-1 rule was tested by Antelmi, Malandrino, and Scarano who found that, at least on Twitter, “lurkers are less than expected: they are not 9 out of 10 as suggested by Nielsen, but 3 out of 4” (1035). More likely, these numbers are not only contingent on social media platform but also fluctuate, especially given how our own lurking behaviors have changed over time. Nevertheless, the general perception that a large proportion of social media users are lurkers can create anxiety about active engagement via posting or commenting. Lurking contributes to sneaky rhetorics as it locates users on different sides of surveillance, whether as the one being surveilled without knowledge of who’s doing the surveilling, which contributes to feelings of anxiety, or as the one surveilling others, which makes all the more apparent how surveillance happens. And although lurking can feel like a protective and guarded way of interacting with Facebook, it is important to note that just because we aren’t clicking the “share” button or otherwise publicly interacting with the interface doesn’t mean that we aren’t actively contributing to Facebook’s database and implicated in processes of dis-/misinformation.

How do sneaky rhetorics contribute to misinformation and perhaps even the propensity for large groups of people to find resonance with disinformation campaigns such as QAnon, Pizzagate, and Plandemic? Sneaky rhetorics stick, and we posit that they become habitual sensibilities of mistrust as they are cultivated by social media platforms via practices like lurking, which create the feeling that there are important things happening behind the scenes that we don’t know about. We suggest that these feelings of mistrust fuel compulsive Facebook use and often lead to truth-seeking behaviors including increased information consumption (such as via doomscrolling) rooted in a desire to find out what’s really going on (Elhai et al.; Dempsey et al.). When information consumption happens at a fast pace and great volume, users are not always vigilant about checking the credibility of those sources (which seems to have led to a proliferation of fact-checking websites), and they can even pick up and pass on misinformation unintentionally. For example, we are thinking of a phrase that at least some of us hear ourselves saying often: “I read somewhere . . . ”. Further, when consuming vast quantities of information, users often—whether consciously or not—latch onto “answers” that align with their existing political commitments and concerns, whether those answers point to essential oils, chemtrails, or vaccine skepticism. These feelings of mistrust stick and we bring them with us to our personal interactions, especially on Facebook, which is oriented around relationships.

Compulsive use also makes social media users more open to dis-/misinformation, especially when they consume vast amounts of information in the in-between moments of everyday life and its stresses. As discussed earlier, we found that our Facebook use was more habitual and compulsory than we might have anticipated prior to our study, a finding that reflects Chun’s formulation of habits as “practices acquired through time that are seemingly forgotten as they move from the voluntary to the involuntary, the conscious to the automatic,” and become embedded in people and communities (6). As a result, we were more attuned during the study to how we experienced bursts of news about racist and antisemitic harassment and threats within the academy, memories sharing testimonials about sexual assault, and other flashes of distressing content in the split seconds between thoughts during a meeting. While we noted the affective experience of these quick encounters as a result of the study, we reflect that these feelings often do not register into our consciousness due to the tempo and frequency of habitual Facebook use. In addition to considering how such abrupt experiences with difficult material—at times amidst anxiety-driven doomscrolling—affect our well-being as social media users, we must also consider the consequences of involuntarily and habitually engaging with content that is inaccurate or untrue.

In addition, the reasons why we stay on Facebook—the positive feelings and emotional attachments toward the platform because of how it helps us stay close to family and friends—works in tandem with more unsavory sensibilities to enable disinformation. Our above discussion of how Facebook cultivates senses of comfort and closeness to friends and family who may be at a distance when we message, browse, “like,” or otherwise react to their posts—even while we feel anxiety about Facebook more generally—may speak to how the ambivalent sense of being both uninvested and attached begins to stick. Our results additionally raise the question of how this simultaneous sense of closeness and detachment might render users vulnerable to disinformation. That is, are feelings of trust sustained when engaging with less credible content? When feelings of closeness or situatedness stick before immediately shifting to some other interaction such as browsing content or lurking on people in whom we are much less personally invested, is there is a risk of taking the site, the person, or the content much more seriously than we might have taken an interaction with that person or content otherwise? We suggest, in other words, that sneaky rhetorics speak to how feelings of trust implied in sensibilities of stability and closeness are sustained through habitual repetition when encountering content that may be less trustworthy.

Conclusion

In this article, we discussed how the concept of sneaky rhetorics provides a way of understanding the relationship between everyday behaviors such as browsing or lurking on Facebook and the problem of disinformation online. That is, this project provided us with a sense of how social media technologies prime users to accept particular kinds of information as truth through habitual, repetitive actions that stick affectively, and we did so through the development of the method of affective time use study. More specifically, understanding user interactions such as lurking and doomscrolling in terms of affect enables us to interpret them as habitual behaviors that encourage disengaged mindsets. Such sneaky rhetorics can lead to increased consumption of online information, and obsessive and compulsory doomscrolling can serve to both consume and distract social media users in ways that uphold corporate capitalism and benefit media corporations.

We note that a limitation of our affective time use method was our choice to record our Facebook interactions by hand. Each of us hesitated to use Facebook as we normally would because of the study’s requirement to record our usage. While we each resisted deviating from our normal usage to represent our habits as accurately as possible, the need to record all of our Facebook interactions skewed our usage, especially when using the affective time use method required more effort than the simple act of opening and scrolling. For example, one of us noted that they experienced the urge to scroll on Facebook as part of a previously unconscious nightly routine but had not remembered to bring their time use notes with them to their bedroom and so had to make the conscious choice about whether or not the Facebook use was worth the additional effort to retrieve the data collection instrument. We noted these feelings in our data collection, and the act of doing so helped to foster a heightened accountability regarding our Facebook use while also drawing attention to how unconscious our typical usage really is. As a result, the study positioned us to be more conscious of our daily rhythms of social media use than we typically are, and even disrupted those rhythms. We believe this is a noteworthy point because habitual, disengaged mindsets may not be the most attuned to critical engagement with news and political content on the site.

Consequently, our approach to documenting social media habits through the affective time use method might be a helpful way of breaking habits of mindless interactions with social media that negatively impact affective well-being (Verduyn et al.; Kross et al.). Similar to scholars like Dieterle et al., who have argued that users need to be more mindful about circulating dangerous, harmful, or incorrect content, even to criticize or counter such information, we suggest that users can resist the affective habits encouraged by social media by fostering more awareness of their own browsing habits. We thus suggest that anyone interested in being more reflexive and purposeful about their engagement with social media adapt our research instrument in Figure 1 to collect data about their own Facebook use. Those interested in using this method might further consider how everyday habits and daily rhythms of use serve as a kind of affective conditioning, as well as how these conditions have cultural, social, and political implications. We suggest that doing so may elucidate the ways in which social media pre-positions its users toward harmful affective responses that can make one susceptible to networks of dis-/misinformation. In addition, we could see this method being implemented within a college writing course as a way of facilitating reflection and conversation about the changing contexts of writing given the current media landscape.

Campaigns against dis-/misinformation should not be constructed merely as human versus machine; instead, there is a need to consciously consider how our interactions and affective responses are critical to rhetorical processes of dis-/misinformation as well as how they may possibly ameliorate dis-/misinformation. This point speaks to the need for more research about—and attention to—the role of affect and user embodiments and intimacies in processes of disinformation online and the role of digital interfaces in facilitating these processes, and we call for future studies that take up this concern. Although we focused in particular on browsing and lurking in this article, there is additionally room for further consideration of how affectively loaded terms used to talk about user interaction on social media, such as doomscrolling, FOMO (fear of missing out), and “feeling attacked” or “seen,” can be further examined in terms of their affective and political implications. For digital rhetoricians in particular, our findings also suggest a need for more critical studies of our affective attachments to information consumption, including how consuming large amounts of information online can be an act of self-soothing in anxious times. Finally, a future study could use the research instrument that we developed on a different social media platform or with a larger sample of participants as a way of generating more data on users’ affective experience of social media. In doing so, we may gain a better understanding of how sneaky rhetorics operate on other platforms for people across contexts.

[1] For context, this article is an extension from Sano-Franchini’s presentation at the Alabama Symposium on Digital Rhetoric. Because her presentation was based on her 2018 Technical Communication article, “Designing Outrage, Programming Discord: A Critical Interface Analysis of Facebook as a Campaign Technology,” we asked Amber Buck and Cindy Tekkobe if we could submit for this special issue a follow up study on affect and emotions on Facebook, and they agreed. So, in late 2019 and early 2020, we designed and conducted a study of our affective experiences on Facebook.

Ahmed, Sara. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2014.

Anand, Nitin, et al. “Doomsurfing and doomscrolling mediate psychological distress in COVID‐19 lockdown: Implications for awareness of cognitive biases.” Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 2021, pp. 1–3.

Antelmi, Alessia, et al. “Characterizing the Behavioral Evolution of Twitter Users and the Truth Behind the 90-9-1 Rule.” Companion Proceedings of the 2019 World Wide Web Conference, San Francisco, CA, 13–17 May 2019, doi.org/10.1145/3308560.3316705.

Bakir, Vian, and Andrew McStay. “Empathic Media, Emotional AI, and the Optimization of Disinformation.” Affective Politics of Digital Media, edited by Megan Boler and Elizabeth Davis, Routledge, 2021, pp. 263-279.

Benjamin, Ruha. Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Polity, 2019.

Buck, Amber. “Examining Digital Literacy Practices on Social Network Sites.” Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 47, no. 1, 2012, pp. 9–38.

Chen, Fei-Ching, and Hsiu-Mei Chang. “Engaged Lurking: The Less Visible Form of Participation in Online Small Group Learning.” Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, vol. 8, no. 1, 2013, pp. 171–99.

Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong. Updating to Remain the Same: Habitual New Media. MIT Press, 2016.

Coded Bias. Directed by Shalini Kantayya, 7th Empire Media, 16 Oct. 2020. Netflix, https://www.netflix.com/title/81328723.

Cohen, Dale J., et al. “A Time Use Diary Study of Adult Everyday Writing Behavior.” Written Communication, vol. 28, no. 1, 2011, pp. 3–33.

Dempsey, Abigail E., et al. “Fear of missing out (FoMO) and rumination mediate relations between social anxiety and problematic Facebook use.” Addictive Behaviors Reports, vol. 9, no. 100150, 2019, pp. 1–7.

Dhir, Amandeep, et al. “Online Social Media Fatigue and Psychological Wellbeing–A Study of Compulsive Use, Fear of Missing Out, Fatigue, Anxiety and Depression.” International Journal of Information Management, vol. 40, 2018, pp. 141–152.

Dieterle, Brandy, et al. “Confronting Digital Aggression with an Ethics of Circulation.” Digital Ethics: Rhetoric and Responsibility in Online Aggression, edited by Jessica Reyman and Erika M. Sparby, Routledge, 2019, pp. 197–213.

Elhai, Jon D., et al. “Fear of Missing Out: Testing Relationships with Negative Affectivity, Online Social Engagement, and Problematic Smartphone Use.” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 89, 2018, pp. 289–298.

Eubanks, Virginia. Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor. St. Martin's Press, 2018.

Gelms, Bridget. “Volatile Visibility: How Online Harassment Makes Women Disappear.” Digital Ethics: Rhetoric and Responsibility in Online Aggression, edited by Jessica Reyman and Erika M. Sparby, Routledge, 2019, pp. 179–194.

Gruwell, Leigh. “Feminist Research on the Toxic Web: The Ethics of Access, Affective Labor, and Harassment.” Digital Ethics: Rhetoric and Responsibility in Online Aggression, edited by Jessica Reyman and Erika M. Sparby, Routledge, 2019, pp. 87–103.

Hart-Davidson, William. “Studying the Mediated Action of Composing with Time-Use Diaries.” Digital Writing Research: Technologies, Methodologies, and Ethical Issues, edited by Heidi A. McKee and Danielle Nicole DeVoss, Hampton Press, 2007, pp. 153–170.

Krishnamurty, Parvati. “Diary.” Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods, edited by Paul J. Lavrakas. Sage Publications, Inc., 2008, pp. 198–9.

Kross, Ethan, et al. “Facebook Use Predicts Declines in Subjective Well-Being in Young Adults.” PLoS ONE, vol. 8, no. 8, 2013, pp. 1–6.

Lauren, Ben. “Experience Sampling as a Method for Studying In Situ Organizational Communication.” Journal of Organizational Knowledge Communication, vol. 3, no. 1, 2017, pp. 63–79.

Lee, Yu-Wei, et al. “Lurking as Participation: A Community Perspective on Lurkers' Identity and Negotiability.” Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Learning Sciences, Bloomington, IN, June 2006, https://repository.isls.org/bitstream/1/3531/1/404-410.pdf.

Leon, Kendall, and Stacey Pigg. “Graduate Students Professionalizing in Digital Time/Space: A View from ‘Down Below.’” Computers and Composition, vol. 28, no. 1, 2011, pp. 3–13.

Lotier, Kristopher M. “What Circulation Feels Like.” enculturation: A Journal of Rhetoric, Writing, and Culture, no. 26, 2018, http://enculturation.net/what-circulation-feels-like.

Mak, Aaron. “Facebook’s New TV Ad Doesn’t Inspire a Lot of Confidence.” Slate, 27 Apr. 2018, https://slate.com/technology/2018/04/facebook-new-ad-accidental-reminder-biggest-problems.html.

Nelson, Julie. “Complex Rhetorical Contagion: A Case Study of Mass Hysteria.” enculturation: A Journal of Rhetoric, Writing, and Culture, no. 28, 2019, http://enculturation.net/complex_rhetorical_contagion.

Nielsen, Jakob. “The 90-9-1 Rule for Participation Inequality in Social Media and Online Communities.” Nielsen Norman Group, Oct. 2006, https://www.nngroup.com/articles/participation-inequality/.

Ngai, Sianne. Ugly Feelings. Harvard University Press, 2004.

Noble, Safiya Umoja. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York University Press, 2018.

O'Neil, Cathy. Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. Crown, 2016.

Osatuyi, Babajide. "Is Lurking an Anxiety-Masking Strategy on Social Media Sites? The Effects of Lurking and Computer Anxiety on Explaining Information Privacy Concern on Social Media Platforms." Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 49, 2015, pp. 324–32.

Preece, Jenny, et al. “The Top Five Reasons for Lurking: Improving Community Experiences for Everyone.” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 20, no. 2, 2004, pp. 201–23.

Price, Matthew, et al. “Doomscrolling during COVID-19: The Negative Association Between Daily Social and Traditional Media Consumption and Mental Health Symptoms During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” PsyArXiv, 2021, https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/s2nfg.

Reyman, Jessica, and Erika M. Sparby, eds. Digital Ethics: Rhetoric and Responsibility in Online Aggression. Routledge, 2019.

Rozgonjuk, Dmitri, et al. “Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) and social media’s impact on daily-life and productivity at work: Do WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat Use Disorders mediate that association?” Addictive Behaviors, vol. 110, no. 106487, 2020, pp. 1–9.

Sano-Franchini, Jennifer. “Designing Outrage, Programming Discord: A Critical Interface Analysis of Facebook as a Campaign Technology.” Technical Communication, vol. 65, no. 4, 2018, pp. 387–410.

Sparby, Erika M. “Reading Mean Comments to Subvert Gendered Hate on YouTube: Toward a Spectrum of Digital Aggression Response.” enculturation: A Journal of Rhetoric, Writing, and Culture, no. 33, 2021, http://enculturation.net/readingmeancomments.

Stark, Luke. “Algorithmic Psychometrics and the Scalable Subject.” Social Studies of Science, vol. 48, no. 2, 2018, pp. 204–31.

Stark, Luke. “Empires of Feeling: Social Media and Emotive Politics.” Affective Politics of Digital Media, edited by Megan Boler and Elizabeth Davis, Routledge, 2021, pp. 298–313.

Verduyn, Phillippe, et al. “Passive Facebook Usage Undermines Affective Well-Being: Experimental and Longitudinal Evidence.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, vol. 144, no. 2, 2015, pp. 480–8.

Wachter-Boettcher, Sara. Technically Wrong: Sexist Apps, Biased Algorithms, and Other Threats of Toxic Tech. W. W. Norton & Company, 2017.