Zosha Stuckey, Syracuse University

Enculturation: http://enculturation.net/staring-back

(Published November 23, 2010)

|

Figure 1: Lavinia Warren, c. 1880. Charles Eisenmann, photographer. Ronald G. Becker collection of Charles Eisenmann photographs, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Library |

It seemed impossible to make people at first understand that I was not a child (45). --Lavinia Warren, Autobiography of Ms. Tom Thumb, 1901 |

|

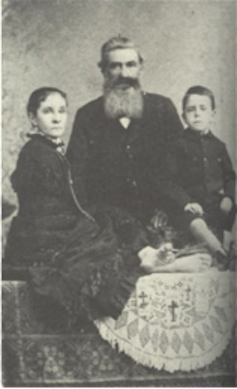

Figure 2: Ann E. Leak with her husband and son, c. 1884. Charles Eisenmann, photographer. Ronald G. Becker collection of Charles Eisenmann photographs, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Library |

And, first of all, I beg you not to regard me as an ordinary show character or traveling mendicant (5). --Ann E. Leak, Born Without Arms, 1871 |

Introduction

In the quotations above and consistently throughout their autobiographies, Lavinia Warren and Ann E. Leak are both astutely aware of the pernicious perceptions of their audiences, and thus, vigorously attempt to alter them. In the images above, Warren smiles confidently; Leak appears more vexed. Warren works to be taken seriously; Leak appears seemingly battered by consistent attempts to be viewed not as a monster but as human. Yet, generally speaking, a nineteenth century freak show audience probably would not have immediately considered either woman as deserving of seriousness or humanity. In fact, their divergent embodiments—Warren was a person of small stature and Leak had no arms—most likely conjured a sort of rhetorical failure.

My interest in recovering the rhetorical histories of these women began here with the idea that women with disabilities have not been given the sort of historicity or rhetoricity they deserve. My role as researcher arose not only out of a “passionate attachment” to uncovering ways that women with disabilities have asserted themselves rhetorically, but also from the idea that studies of disability and rhetoric must move beyond analyses of exploitation.1 The fact of exploitation remains important, but a more nuanced inquiry urged me to evoke what Paul Longmore has called "positive disability culture" where we transform our conception of disability from that of a biological deficit to a celebrated social, cultural, historical, and political identity.2 In contesting the absence of women with disabilities in rhetorical histories, I also build on Cynthia Lewieki-Wilson and Jay Dolmage’s challenge in Rhetorica in Motion (2010) for scholars in rhetoric to reveal “the ways that rhetoric became disembodied and rhetorical fitness came to be ascribed to just a narrow range of (white, male, able) bodies. [ . . . ] This normative matrix comprises a narrow range of rhetorical ability, which is impossible to maintain; it also overlooks the ways that rhetors make use of disability as rhetorical power” (27). By discussing Leak and Warren’s self-fashioning, I am responding to Lewieki-Wilson and Dolmage’s call to expand rhetorical fitness beyond “the good (white, abled) man speaking well” which helps us imagine ways women with disabilities have historically used their bodies to exercise rhetorical ability.

But for Leak and Warren, this fitness does not necessarily come in the form of a direct or uncomplicated self-fashioning or "speaking back;" rather, I find myself having to tap the rhetorical subjectivities of these women by disentangling traces of agency that are enmeshed within a complex web of textual accretions. That is, it is possible to gain glimpses of agency as it evolves through language, but that agency and staring back is always fragmented and fleeting. I attempt to reclaim some agency for these voices, even while I question and disrupt any pure notion of agency. We come to know Leak and Warren from layered historical texts, sometimes self-authored and sometimes not, in which I imagine agency and subjectivity as a dynamic and constructed historiographic endeavor: that is to say, we can never know a "real" Leak or Warren.

Working within the traditions of disability studies, feminist rhetorics, and rhetorical historiography, I envision Leak and Warren in terms of their rhetorical abilities which means I look at how both women use rhetoric to the point where, I argue, they out-maneuvered physiognomics (when outward appearance is thought to correlate to inward character) and instead achieve at least some semblance of rhetorical fitness. The freak show platform offered these women a remarkable opportunity to be seen and heard and to show how rhetoric can be effective when deployed through different bodies.

The work of feminist scholars such as Karlyn Kohrs Campbell (1989), Nan Johnson (1991), and others (Logan; Mattingly; Royster; Cobb; Buchanan) has shown that Victorian women who were typically denied access to public, gendered, and raced spaces adapted their rhetoric and spoke in public often by, as Johnson argues, “domesticating the public platform.” Johnson’s work in particular shows how women’s rhetorical power was constrained by a domestic ideology she frames as "parlor rhetoric;" even when they spoke in public, women were constrained by “parlor-like,” feminized rhetorics (145). Victorian parlor rhetorics included language and bodily performances in which women demonstrated their "essentialist feminine identity" in parlors, and, Johnson goes on to discuss how women also were expected to adopt parlor conventions when they appeared on the public platform (120). The parlor conventions that were part of the Cult of Domesticity (which includes True Womanhood and Republican Motherhood) restricted women to being "noble maids" or "eloquent mothers" who reiterated the maternal, feminine qualities of piety, purity, submissiveness, and domesticity as central to rhetorical practices of letter-writing, elocution, and conversation. Similarly, Leak and Warren, continually affirmed their true womanhood in the spaces of parlors and private “receptions” as well as in large, civic venues such as concert halls, museums, and schools. But no matter how flawless their performance of femininity, due to the able-bodied gaze that peered with anxiety at them continually, Leak and Warren would never fit entirely into gendered norms. Leak and Warren could never perform “domestic virtues unambiguously” (Johnson 121) because they had the additional rhetorical obstacle of having to negotiate an “aesthetic nervousness” (Ato Quayson) and cultural anxiety associated with the extraordinary body.3 This anxiety over bodily variation intersected with the gendered anxiety Johnson talks about as restricting women to parlor conventions; but for Leak and Warren, they carried a unique burden of being able to achieve the gender conventions of piety, purity, submissiveness, and domesticity and still never reaching full considerations as a “true” women. In this article, I offer a new perspective on parlor and feminist rhetorics by constructing Leak and Warren as practitioners of parlor rhetorics who had to negotiate beyond gender constraints and thus I show how disability can function as a generative category for analysis at the intersection of gender.

Similar to the ways feminist historians of rhetoric have argued that we need to recover the erasures of women in history (Lunsford; Glenn; Logan; Gere; Mattingly; Royster; Kates; Mountford; Sharer; Buchanan), and in conversation with recent scholarship on methods (Working in the Archives; Rhetorica in Motion; Beyond the Archives), disability studies scholars (Lewieki-Wilson; Dolmage; Brueggemann; Vidali; Price) are beginning to argue that we need to recover and re-write disability into rhetoric. These scholars argue that when disability has been considered, it has been equated with defects in character or as biological deficit rather than as a signifier of power. The examples of physiognomic correlations are almost too numerous to cite but include the divergent embodiments and rhetorical failures of Thersites, Diomedes, and Telemachus among others (Fredal 18; 31-34). The rehabilitation of Demosthenes and his transformation from the normal to the abnormal (non-stutterer to stutterer) acts as one grand mythos in histories of rhetoric. Other examples that demonstrate the need for recovery and revision include instances where advocates for disabled people are discussed, but rhetorical agency is never given to disabled people themselves. We also need to be careful when discussing metaphors that compare women and African Americans to “idiots” without pointing to the problematic nature of the comparison also for people with disabilities. And, while Rhetoric Review (2003) published a compelling and exciting symposium entitled “Representing Disability Rhetorically,” little was included that directly connected disability to feminist rhetorics or histories of rhetoric.4

In contrast is Jay Dolmage’s generative (re)historicizing of the disabled Greek God Hephaestus as rhetorically abled (published also in Rhetoric Review). Dolmage depicts Hephaestus as a disabled god whose disability is his ability; his out-turned, “deformed” feet give him the agility to move sideways and this contributes to his industriousness. Hephaestus’ bodily variation leads us to epistemological and rhetorical understandings of disability rather than solely negative constructions.

Rather than “reading history normatively” and deploying “disability as deficit,” I re-read Leak and Warren into rhetorical history by showing how they used their bodily variations to assert rhetorical fitness and agency—how they accessed public spaces, how they recognized but also resisted their othering, and how they attempted to refashion their ethos from that of a “vulgar,” laughable, and “disgusting unfortunate” to that of a “true” and pious Victorian woman and an esteemed public figure.5 In this context, rhetorical fitness can be viewed as the abilities to use rhetoric to: 1) achieve a public presence, 2) be conscious of dynamics of power and Othering, and 3) move one’s situated ethos into a desired ethos” through self-definition and self-fashioning.6 Rhetorical fitness in these circumstances is the ability to “stare back” at an audience amidst a potentially disastrous staring encounter.7 Rhetorical fitness is thus recast through embodied difference as having the ability to deploy (dis)ability in strategic and useful ways. Leak and Warren evolve as capable, humanized citizens—“fit” in the sense, not that they overcame their disabilities, but rather that they used them to reach public and textual spaces typically not accessible to people with disabilities.

A Fraught Public Platform

That people with visible disabilities were seen at all in public in the nineteenth century was a unique phenomenon. By appearing on the platform, freak show performers were propelled into public spaces that, during Leak and Warren’s time, were not necessarily accessible to them outside of the freak show industry. These women wrote their autobiographies and appeared in public at a time when disabled people in the late nineteenth century preached from the pages of unpublished life narratives, from the street corner in the form of “mendicant literature” (if they could avoid arrest), and from the institution but rarely if ever from the lectern or podium or the published manuscript. In detailing the “ugly laws” that regulated appearance and visibility, Sue Schweik points to an 1894 Pennsylvania law that disallowed the showing of physical and mental deformities for the collection of alms (62). According to Schweik, although New York City had no “ugly law” on the books in 1896, the police chief vigorously sought to arrest those who were “exhibiting” their afflictions and deformities merely by being in public.8 Because access to the podium and public space for non-normative bodies was vigorously policed, if not entirely disallowed, other available means such as parlor side shows and more public freak show platforms and were exploited.

And, once the platform was reached, women with bodily variations who did appear in public as freak show performers were caught between the polarities of, on the one hand, self-naming and agency, and on the other hand, constructions that evoked vitriol. As Rosemarie Garland-Thomson tells us, performers were “scrupulously described, interpreted, and displayed” by others and turned into people who were seen as “solely bodies, without the humanity social structures conferred upon more ordinary people” (Freakery, 7; Extraordinary, 56-7). Likewise, Robert Bogdan reveals that “The major lesson to be learned from a study of the exhibition of people as freaks is not about the cruelty of the exhibitors or the naiveté of the audience [ . . . rather] how we view people who are different has less to do with what they are physiologically than with who we are culturally” (10). Garland-Thomson agrees with Bogdan that the identity of the freak is manufactured by socially constructed practices—by ways people think about and act towards freaks. However, I move this discussion further by looking at not only how people thought about and reacted to freaks but also how the performers took action to (re)construct themselves.

Deliberation over the ethics of freak shows have continued to oscillate between these issues of self-representation and what has been considered oppressive social constructions: one camp maligns performances as fraught, exploitative, and dehumanizing while another camp celebrates the artistry, cunning, economic independence, and self-representation that performers can attain. While Garland-Thomson and Bogdan both agree that P.T. Barnum owned, designed, controlled, and exhibited his “curiosities,” scholars such as Eric Fretz and Michael Chemers have considered possibilities that the formation of a public self for performers was an autobiographical act which becomes, according to Fretz, an “achievement of self-construction and the rhetorical shaping of a public persona” (99). This attempt to identify where rhetorical agency lies in the construction of freaks is a central tension in freak show scholarship and is of particular interest in my study of these two women.

That these perspectives are mutually constitutive and simultaneous (surely Bogdan and Garland-Thomson believe in the autobiographical act) makes the freak show and study of the freak show a relentlessly fraught enterprise. Leak and Warren are simultaneously exploited and liberated, simultaneously self-represented and constructed by someone else. This is why the issue of agency is so fraught. While the freak show should not be seen as entirely liberating or wholly oppressive, nor should the freak be thought of as entirely self-representing--but still there were consequences to performing on the public platform. While both gender (Cheryl Glenn) and disability (Garland-Thomson) signify relations of power, the institution of the freak show exemplified how power circulated in particular ways to transfer the anxieties of those who lived in a fictional world of normalcy onto a disabled Other. This transference is analogous to the ways Johnson theorizes cultural anxieties that arose when women spoke in public; but whereas some women could adapt their performance of femininity for each rhetorical situation, freak show performers often could not change their corporeal variations. In one of the earlier books on freakery, Leslie Fiedler theorizes “the sense of quasi-religious awe” we feel as observers of freaks. This ideological colonization serves to reinforce the normality of the observer or “normate.”8 In this sense, the freak show industry thus burgeoned from 1840-1920 as the country sought out ways to unify its national identity (i.e. an “American” ideal of white, Christian, male, and able-bodied) by comparing itself to what Garland-Thomson calls the “ultimate Other.” Leak and Warren, like their female counterparts who tried to speak in public, do the cultural work of resisting a displacement of fear and anxiety. While Fiedler depicts the confrontation between “freak” and “normate” as horrific and traumatic, Leak and Warren look to alter the encounter. And to do so, both women struggle for self-representation and agency. Their greatest rhetorical obstacle lay not in reaching the platform, but in the attempt once there to gain some respect beyond that which was afforded to them through adhering to gender conventions.

Lavinia Warren

Lavinia Warren was born in Middleboro, Massachusetts on October 31, 1841 to a wealthy family that claims descendency from passengers on the Mayflower. In her monograph, The Autobiography of Ms. Tom Thumb: Some of My Life Experiences (1901/1979), Warren emphasizes this fact of her well respected New England lineage as a way to counter perceptions of her as unfortunate, revolting, and pitiable and instead to bolster perceptions of her as the “pure” Victorian woman. Warren casts herself as an elite New Englander and as an esteemed, patriotic citizen whose grand social stature might offset some of the conceptions people had of her small physical stature. Warren, like Leak, briefly taught school; the fact that both women were schoolteachers demonstrates their initiative and successes in attaining normative cultural roles for women at the time. Warren, however, dissatisfied with teaching was attracted to the entertainment industry by its glamour and potential for travel. At the age of 16, Warren decided to exploit her “proportionate dwarfism" and began working in show business on her cousin’s floating museum of curiosities. People with proportionate dwarfism at the time were called “midgets” but Warren never refers to herself as either "dwarf" or "midget." While this move to work as a "public character" (Warren 39) took her out of the realm of the domestic, she would eventually be invited by P.T. Barnum, who took over management of Warren, to meet another one of his acts known by the name of General Tom Thumb. Warren soon married Charles Stratton (aka General Tom Thumb) and by 1863 with her highly publicized courtship, marriage, and honeymoon she had become of the world's most famous bride.

The image below is of Warren and Stratton on their wedding day at the Metropolitan Hotel in Manhattan. While the image portrays the couple on a balcony as if an oration would ensue, the only words recorded that night as spoken by either newlywed was a short phrase by Stratton; Warren remains the “quiet woman” while Stratton is recorded as uttering nothing more than a simple “Goodnight all!” (“The Loving Lilliputians;" Frank Leslie’s Journal). Though I could find no other quotations from either Warren or Stratton in mass media publications of the time, Warren later counterbalances this textual silence with the autobiography.

Lavinia Warren and husband Charles Stratton. 1863.

A. Bogardus (photographer).

Ronald G. Becker collection of Charles Eisenmann photographs, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Library

The couple’s elaborate wedding took place in Grace Episcopal Church in New York City. The Astors and the Vanderbilts were said to have attended as Barnum sold tickets for $75. The New York Tribune reported that “as the little party toddled up the aisle a sense of the ludicrous seemed to hit many a bump of fun and irrepressible and unpleasantly audible giggle ran through the church.” The event was real, certainly, in the sense that Warren and Stratton married legally; however, the marriage, which ended up on the cover of Harper’s Weekly also was said to have been a farce—laughter was heard throughout the church, and Barnum was said to have orchestrated the entire event (New York Tribune). Even amidst some of the more contemptuous reactions they received, Warren and Stratton spent part of their honeymoon at the White House with the Lincolns and met Queen Victoria in the same year. Warren, in the beginning of her career, was paid an astounding $1000 a week by Barnum, a fact that at least partially revises claims of economic exploitation often considered part of freak shows (Warren 51). After years of performances that allowed the couple to travel the world, Stratton died in 1883. Warren remarried and continued to perform for “my public” (her words) until her death in 1919. Near the end of the autobiography, she writes, “When asked if I don’t get tired of this public life, I am wont to answer that in a sense I belong to my public” (Warren 172). Warren, while certainly aware of some of the more mortifying receptions she received while on display, took pride in her accomplishments as a well-known female performer.

That is to say, as she knew she was routinely laughed at, she also attempted to recast public perceptions of her—it is this attempt at redefinition that makes her so rhetorically competent. Warren’s autobiography becomes an occasion for her to demonstrate how she at times spoke back and resisted transfers of fears onto her in her lifetime. The publication and existence of the text itself also is a sort of speaking back; and finally, my project goes so far as to uncover the ways in which, after publication, her attempts at self-definition and textual competence have been disregarded. I would not have so clearly understood her attempts at redefinition were it not for her editor’s explanations in his introduction to her book that, I argue, misrepresent Warren. Warren’s historical recovery is incomplete without an appraisal of this layering; if we do not pull back the layers of rhetorical accretion, we risk recasting the anxious gaze (which, in the end, may be unavoidable anyway).9

In the text, it is from an acknowledgement of her marginal position as Other that Warren attempts to alter perceptions of herself as inferior. Throughout the book, she mentions how her visitors receive her with morbid curiosity; they receive her, she writes, with a “critical gaze” (31). She begins the text, “During my long and eventful public career there has even been earnest inquiry by nearly all with whom I have come in contact at my receptions and entertainments as to my birthplace, parentage, ancestors, habits, etc.[ . . . ] especially asking ‘Whar was you raised?’ as if I were a rare plant or a curious quadruped” (31). Warren is obviously aware of the mortifying manner in which she is received and goes so far as to quote a man at length who, from a eugenics standpoint, questions her intelligence (32). She tells the story of how this man who speaks to Bleeker, her manager, is well aware that she is listening in. She tells how this man goes on to correlate intelligence to head size: surely the man contends, since Warren is small, so is her brain. Bleeker’s response is to mock the man (and stand up for Warren) by sarcastically urging him to write a letter to Barnum so that Barnum, in choosing employees in the future, might do well to choose “the largest-headed giant,” Warren concludes the story “and glancing pityingly at me he [the man who had mocked her] walked out of the hall fully convinced that I did not possess ‘good common sense’” (32). Warren, however, does not respond directly to the man who offends her in the story above because it would not have been appropriate for a woman to respond directly to—or, confront and disagree with—a man. Warren often uses the words of men (in the way she relied on Bleeker in this story) to assert her own authority, a paradoxical form of agency that is, as Johnson, Lindal Buchanan, and others have theorized, a typical gendered rhetorical convention of the time.

To understand how she uses the words of men, it is necessary to look at the layering or rhetorical accretion that comes about over time. An example of Warren’s rhetorical use of the words of men is apparent in her use of Barnum and Bleeker’s words that she “borrowed” from their writings. But this rhetorical use is misunderstood by A.H. Saxon (Warren’s editor of the 1979 edition) when he talks about how Warren “plagiarizes” heavily from Barnum’s autobiography, from Bleeker’s account, and from pamphlets advertising her and Stratton. The editor of her autobiography, Saxon, goes on to comment upon the fact that Warren lifts large portions of her text from Bleeker’s text: “No doubt Lavinia’s memory, at the distance of thirty years, required some prodding, and the temptation to plagiarize from her former manager’s highly readable account obviously proved irresistible” (14).

Yet, to view Warren’s reliance on Bleeker and Barnum’s words as plagiarism, as Saxon views them so many years later, is to deny her credit for the rhetorical move of revising Barnum and Bleeker's words as a way to re-invent herself. If we fail to see how she is reinventing herself, we read history normatively. Warren is not plagiarizing but rather taking back ownership of her own experiences that Barnum and Bleeker have depicted as central to themselves. In the following example, Saxon (editor of her book published in 1979) mentions how Warren uses without citing, in other words plagiarizes, from Barnum’s 1872 autobiography. As Saxon himself indicates: “As not infrequently happens when Lavinia is quoting from her sources, she has made a few changes and deletions in the original, including two references to her as a 'dwarf.’ The original passage she quotes begins as follows ‘In 1862 I heard of an extraordinary dwarf girl named Lavinia Warren’ ” (183). But when we look to Warren’s text itself, she has excised the word “dwarf” from the Barnum quotation and quoted Barnum instead as writing, "In 1862 I heard of an extraordinary little woman named Lavinia Warren" (49). Many possibilities exist for her omission of the word “dwarf.” Most importantly, this move could have been a means to resist others’ attempts to name her. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, whereas the word midget was coined in 1865, the word dwarf appears as early as 700. In Warren’s lifetime, then, a midget was distinguished from a dwarf—midget was used to categorize people of small stature whose bodies were proportionate (which would have technically described Warren) versus dwarf, which was used to categorize people of small stature who were not proportional. Warren may have been attempting to dissociate herself from the devalued nomenclature of dwarf. From this perspective, we can not consider Warren’s edits as a clear case of plagiarism, but we can consider them as a form of evidence of cunning—a form of rhetorical fitness that aids in her self-fashioning and her movement towards a more desired ethos.10

The autobiography offers a few occasions not only for Warren to speak back in these ways and reconstitute herself as fit, but the text stands even further as an exemplar—and an anomaly—of a performer’s attempt to control her own representation. The almost entirely ignored genre of freak show autobiographies and chapbooks generates multiple tensions that help explain the uniqueness of Warren’s rhetorical agency. The autobiography is unique in that unlike Leak’s chapbook (as I will discuss later) 1) it was published outside of the profit-driven marketing of freak show industries, 2) it is considered beyond a doubt to be authentically written by the performer herself, and 3) most of what is in the autobiography is considered historical fact rather than display, farce, or deceit. The majority of the words that survived written by people who performed in freak shows between 1840 and 1920 were published as chapbooks mostly for marketing purposes. Most of the chapbooks are assumed (perhaps erroneously) to be invented narratives written by publicists, though I have not encountered any evidence other than hearsay to support this claim. This inability to authenticate authorship of chapbooks creates difficulties when trying to recover words of the performers because it is commonly asserted that the chapbook genre, along with the entire freak show industry, was a hoax (the farcical nature of Warren's marriage is a good example) and therefore the narratives are also a hoax. The text, however, preserved in Warren's handwriting, is able to rise above these tensions which gives her work a certain credibility and historicity that could not otherwise have been obtained.

Nevertheless, even amidst rhetorical facility and these unique successes of the book, Warren’s agency is further complicated by more layering. Approximately 78 years after having been written, A.H. Saxon (as previously mentioned) edited and introduced the first edition of Warren’s autobiography, calling it to his liking The Autobiography of Mrs. Tom Thumb: Some of My Life Experiences. In Saxon’s edition (the only edition), a torn page from the original manuscript is pictured. From this image, it is apparent that whereas Saxon entitled the autobiography The Autobiography of Mrs. Tom Thumb: Some of My Life Experiences, Warren clearly subordinated her identity as the wife of Tom Thumb; rather, she lists the title Some of My Life Experiences at the top and beneath it writes by Countess M. Lavinia Warren formerly Mrs. General Tom Thumb. Use of the appellation “Countess” indicates Warren’s refusal to be viewed as anything other than elegant and decorous. This example as well as other edits made to the autobiography reveal Warren’s efforts at self-representation followed by accretion that undermines those efforts. As the manuscript is finally published, attention is not brought to Warren’s assertions of agency and self-naming. This disregard for her attempts to self-fashion may have worked in a few face to face encounters, as she recounts them in the text, but did not necessarily come to fruition in how she was received after the text's publication. My work in this revisionist project is to confer upon Warren the agency she asserted in her lifetime but also to point out the agency she deserves, but has not yet been awarded, after publication.

Lastly, it is important to consider that it is Warren, not Stratton, who wrote a memoir. Warren’s infinitely famous husband did not evidently author any writings. In addition to Warren’s account, other accounts of the lives of Warren and Stratton were written by their manager, by reporters, and by Barnum. Barnum is known to have written multiple “autobiographies” (each one contradicts the other) that provide accounts of his performers. Barnum’s writings and his advertisements, typically however, took agency away from the performers. 11 The fact of Warren’s self-authored and verifiable text, then, stands not only as an anomaly but actively resists the industry’s tendency to erase linguistic authority of the performers. Amidst this confluence of textual validity and an effort towards self-naming, it is possible to see how Warren reconceives herself. Warren does in fact deploy numerous strategies in order to re-make herself from a “child” or an “unfortunate” into someone who is credible as a true woman.

Ann Eliza Leak

Leak is not as conspicuously assertive as Warren in the tactics she uses to occasionally stare back; rather, Leak expresses more internal anguish, humility, and more subtle resistance over her position as Other. Though in her autobiographical chapbook, Ann E. Leak: Born Without Arms (1871), Leak does not mention the year of her birth, it can be deduced based on her own hard-to-decipher handwritten note attached to the chapbook that she was born either in 1839 or in 1845 without arms in Zebulon, Georgia to religious parents. Her father, Wesley Leak, was a member of the Masons. Leak entered Griffin Female College in Griffin, Georgia at eleven years old and would go on in 1865 at the age of twenty to teach school from her home for only six months, blaming her retirement from that career on the “tediousness” of tending to children. At some point she married William R. Thompson and had a son (Bogdan 217). The autobiography was presumably written after her marriage but before the birth of her son.

Published on inexpensive, low-grade paper and now in extremely deteriorated condition, approximately four original copies of Leak’s chapbook remain. Leak’s text was published but with a different circulation route than Warren’s. Leak’s chapbook was passed out at her exhibits or sent ahead of her to the next town versus Warren’s text which was published and disseminated 78 years after being written.12 This difference is significant because there is little if any afterlife of Leak’s text barring my project. Most likely, at the time of its distribution, the chapbook functioned as a form of advertising. While Warren’s book was not published until long after its composition, Leak’s text circulated within the sphere of her immediate audience.

The persuasive power of this particular chapbook can best be revealed, not within the aim to please or entertain, but rather within the context of Leak’s occasional attempt to recognize, but then go on to subtly defy, the values ascribed to her by dominant culture. Leak, like Warren, sets out to alter the perceptions of her audience. Leak not only acknowledges particular social habits—that people will view her physical difference as unnatural, aberrant, and repulsive—but she does so while attempting also to defy and therefore transform those values. Analysis of the autobiography reveals Leak staring back at times and attempting to achieve fitness. While Warren is aware of an initial disgust with which her viewers approach her, Leak also writes of her acknowledgement of the “pain felt [by her viewers] upon first witnessing such a deprivation” (10). And neither woman is content with allowing her audience to assign deficiency to them. After acknowledging an oppressive gaze, Leak goes on to describe how she then attempts to shift the focus of her dismayed viewers from deficiency to achievement by performing lady-like acts (with her toes) such as drinking tea, doing needlework, hair-braiding, and showing off her penmanship.

In her move towards self-definition as a pious, submissive, and domestic “true” woman, Leak candidly appeals to her audience: “And, first of all, I beg you not to regard me as an ordinary show character or traveling mendicant” (5). In “The Appeal,” she implores her readers—who are soon to be her viewers—to take on a unique and culturally risqué perspective with regards to her. This literal appeal is her most direct attempt at persuasion. In response to the pernicious perceptions and receptions of people with disabilities that she is very aware of, Leak begins the text humbly trying to imagine a new world. But despite her imaginings and her pleas, the consequences of displaying herself ensue: “October 4, 1865. Found myself much embarrassed” (11). A year later, she returns to a self-assuredness that seems to have transcended embarrassment or mortification. She writes, “I have often been asked if I was happy and enjoyed life as well as a person would with arms. Why should I not?” (15). Before reading the chapbook, we (and her other audiences) might assume that she suffered predominantly because of her physical impairment. Yet, Leak is certain to demonstrate that it is not the impairment from which she suffers the greatest but rather from the position she is required to take up as an object of what seems to be unavoidable scorn. Despite her attempts to convince her audience that life as a performer is tolerable and respectable, experience after experience proves displaying oneself hard to stomach. She explains her continued dismay, “October 16, Exhibited at Barnum’s Museum. I cannot begin to describe the feelings of dread and aversion to it that filled my breast, though friends say I did well” (12).

Where Warren found comfort in “friends,” for Leak, even “friendships” she develops as she exhibits are agonizing. She goes on to narrate an evening spent with a Reverend and his family in Palmyra, Missouri: “Sitting in the dining room on the floor [my ital], my plate resting before me, on a napkin. I heard him [the Reverend] ask God’s blessings upon them. [ . . . ] The tears came quickly as I gazed upon them” (16). She delights in being part of their family and being accepted. She probably greatly misses her own family. But it is also possible that Leak cries because she has been placed on the floor to eat. In that same year, she laments, for more than the first time, the pain of having to be among strangers—and she cries again (17). Yet, “the next day I went on exhibition at the Museum” (17). Leak is stuck between the “kindness” (18) of strangers, their “encomiums” (20), and being “all alone in the world” and “an object of charity” (qtd. in Leak from the Southern Herald 20). Leak is not worshipped and courted in the ways Warren is; rather, she relies upon “many little services being rendered gratuitously by parties whose sympathies were interested in behalf of the helpless stranger before them” (22). Another quote, like so many included in the text, comes from Quitman, Georgia where the newspaper reports that “She is a worthy young lady, and wherever she goes, we hope kindness and generosity will be extended to her” (24). For Leak, however, any benevolence shown to her is always complicated by her return the next day to the platform.

Leak needs rhetoric, more than she needs the benevolence of strangers, in order to construct a skilled, virtuous, and accomplished human self. Leak consistently attempts to persuade her audience that she is not a monstrosity as the social constructions might deem her, but rather she is a virtuous and rational woman. In the attempt to conjure her humanity, she and her promoters overdo virtue. The autobiography repeatedly claims that Leak’s choice to exhibit herself is an act of Christian benevolence which aids, even saves, her homeless and destitute family because of the income she can earn. In the narrative, she often surrenders herself to God—it is God in whom she trusts—yet still she never gives up on the strategic power of her words to influence her audience (5). She emphasizes not only her religiosity but also her ability to advance in education, braiding hair, and other “civilized” endeavors open to Victorian era women. We see Leak performing the “noble maid” (Johnson) with precision. As Johnson writes, “By performing domestic virtues unambiguously, a woman speaker could prove that she was a true-hearted woman who ought to be believed” (121). Yet dissonance remained between Leak's desire to be believed for her humanity versus her audience's desire to believe her spectacular nature.

Leak goes on to display herself in various, what could be considered respectable, venues across the country such as Masonic halls, churches, and public meeting places. Her autobiographical chapbook functions as a chronicle of these travels and performances. After approximately 23 years of performances, the last we hear from or see Leak is in the hard-to-decipher handwritten note of 1878 where she attests to the fact that “every person has varying degrees of skills and excellence.” Here, Leak is hopeful; she is capitalizing on the idea that her difference affords her skills and opportunities. In these ways, Leak is like Warren in that she acknowledges that her embodied difference affords her opportunities. Yet while Warren is comfortable with fame and seems to crave the celebrity status, Leak does nothing more than what is required to feed, clothe, and house her family.

As the narrative advances, Leak abandons contemplation of the denigration and “embarrassment” of her performances. Instead of noticing the difficulty that normative social arrangements present to her as a woman with bodily variation, the narrative offers an extensive chronicle of her travels and performances—what she calls “levees”, “engagements” and “public receptions”—with particular emphasis on the “kindness,” “hospitality,” and “warmth” that her “friends” offer her. Her choice of words indicates an attempt to identify with high rather than low brow culture. The words continue to plead for respectability. The majority of the autobiography focuses on the kindness offered to her that often gave her respite from the humiliation of the display. But Leak buries mention of the degradation she openly discusses at the start of the account. The text concludes fairly abruptly with an explanation of familiar rebuke she, and her show, suffers in Savannah, Georgia. Leak publicly defends the show in a response to a newspaper article, suggesting that people in Savannah “misunderstand” the exhibition. She even includes a signed petition attesting to the “propriety” of her occupation. It is here that Leak returns—only momentarily—to an awareness of and resistance to her position as Other. She writes, “This unhappy occurrence [of rebuke] gave my mother an opportunity in seeing what unpleasant and trying situations I am often placed and opened her eyes to some of the obstacles to be encountered in traveling, depending for the patronage chiefly on the curiosity of a capricious public” (34). By ending the narrative with the rebuke suffered in Georgia, it appears that most if not all attempts to tame her impulsive public have seemingly failed. While the bulk of the narrative conceals the degradation she attempts to confront during exhibition, Leak begins and ends with relatively caustic remarks concerning her position in the world. The text concludes with Leak, slightly battered, continuing on her travels.

Like Warren, Leak’s public presence comes with costs and consequences. Within the formation of her public self, she must fashion herself as the epitome of Victorian womanhood, someone who is “highly intellectual, a graduate of Griffin Female College, and, better still, a Christian Lady” (qtd. from The Central Georgian in Born 25). Leak uses piety and virtue more than direct confrontation. Whereas Warren is assertive and less inhibited towards those who have contempt for her, Leak openly begs modestly for respect and justice. Leak assumes she will be judged—and she is, continually; therefore, the text functions as an attempt to intervene in that process of judgment. Leak, like Warren, is engulfed in the drive to affect how others define, view, and understand her. And even though she at times imagines a new ethos, her imagining is scant and ultimately her rhetoric cannot excavate her from the degradation of the freak show.

Conclusion

It is in these writings that we can approach an understanding of resistance, awareness of stigma, and response to able-bodied hegemony: a staring back. Rhetorical practice in the case of these women expands the act of delivery to the stage platform or parlor where the elite of freak show performers entertained famous as well as ordinary guests within the cultural modes of the times. Like their female counterparts who spoke from the platform, these women negotiated cultural anxiety over their appearance in public. While disability discourses in general can assuage national and individual self-apprehension—through laughter, farce, or entertainment—my study complicates the notion of the one-way encounter by showing how these women were not entirely bereft of subjectivity. Rather, life as a freak show performer was a dialogic process in which Warren and Leak did assert agency, construct a self, and respond to derision. Recovering Lavinia Warren and Ann E. Leak demonstrates how women with disabilities maneuvered through multivalent constraints to appear in public spaces and to achieve textual authorship.

Yet however fiercely my project attempts to re-construct the subjectivity and historicity of these women, it is yet another display which re-enacts the side show event. As David Mitchell asserts, “It is impossible [for scholars] to outmaneuver the degradation of the sideshow.”13 Perhaps it is the double-edged, incongruous nature of all rhetoric that both creates as well as solves ethical dilemmas. A unique displacement of anxiety and fear has and perhaps may always be a hallmark of gazing onto (dis)abled Others. Still, revisionist work around these women demonstrates the importance of situating histories of disability within rhetorical paradigms because the stories of these two women force us to contemplate how we value and how we see people with disabilities in the parlor or on the platform. It also asks that we consider their unique rhetorical obstacles.

Our challenge is to move beyond the notion of disability as deficit and beyond the wonder and amazement and arrive at people’s social historicity as rhetorical agents. Rather than debate the degradation of displays and the discrimination people with disabilities have faced, we need to show how and why the social histories and cultural practices matter. It is especially important to revise how disability rhetorics function for people with disabilities in the nineteenth century in the sense that they were not necessarily pitiable victims. Clearly, Leak and Warren led complex and often contradictory lives that cannot be explained as a simple yielding to exploitation or as an unfettered, overt resistance. What we do know is that people with visible disabilities generally could not have accessed speaking podiums or civic and rhetorical fitness in the same ways that orators of the nineteenth century would have. However, that they did reach a platform is of the greatest importance, albeit the stage platform of P.T. Barnum’s lecture room at his American Museum at the corner of Ann Street and Broadway. Rather than simply being mythologized as spectacles or devalued as pawns, the lives of these women need to be taken seriously. Perhaps we need to leave behind certain cultural modes of freak shows; but regardless, there is still a strong need to understand disabled people’s claims of civic and rhetorical fitness.

Notes

1 Jacqueline Jones Royster has familiarized the field with this term. See Traces In a Stream (280). Royster engages in strategic romanticism (Amy Shuman) by using “we” as a way to deeply and passionately identify with the women. Scholarly parameters does not mean giving up passion. She does not proclaim to be objective within this passion.

2 See Longmore and Umansky’s introduction in The New Disability History (2001) where the authors talk about how scholars have turned attention to the culture and values of people with disabilities outside of medical deficit models, patterns of abuse, discrimination, and oppression.

3 Campbell uses the term "Rhetorical obstacle" to signify the social, material, and political hindrances that women faced in the nineteenth century to speaking in public and engaging in public rhetoric.

4 This symposium appeared in Volume 22, No. 2 of Rhetoric Review

5 Dolmage’s phrase "reading history normatively" refers to our tendencies to interpret the past through the notion of disability as deficit.

6 In Traces of a Stream, Royster develops rhetorical theory around the three principles of ethos, context, and rhetorical action while also finding neutral ground between essentialism versus strategic rhetorical patterns that emerge due to similarities in material circumstance. In terms of ethos, she theorizes how sense-making is a rhetorical strategy that helps one move from situated ethos and given circumstance to invented ethos and desired action.

7 “Staring encounter” is theorized by Rosemarie Garland-Thomson. See her newest book, Staring: How We Look, 2009. For Garland-Thomson, staring is an mutual encounter that can result in social change through visual activism. She is interested in the generative aspect of staring. She writes, “Staring is a conduit to knowledge. Stares are urgent efforts to make the unknown known, to render legible something that seems at first glance incomprehensible” (15).

8 "Normate" is Rosemarie Garland-Thomson's term.

9 "Rhetorical accretion" is a phrase used by Vicki Tolar Burton (Collins) signifying layering of perspective that is added onto rhetoric as it circulates. Rhetorical accretion, according to Collins, is that which asks us to sort through the layers of rhetoric that mediate language further away from its source. Collins conceives of rhetorical accretion as a feminist method that comes into play when "the production authority sometimes decides to combine [voices]--for example, to attach an introduction representing a certain ideological viewpoint, to include a dedication indicating who supported the writer, or to publish a work in a volume with other works rather than as a solo text. This process of layering additional texts over and around the original text I call rhetorical accretion. [ . . . ] As in the accreted growth of stones by the addition of external particles, rhetorical accretion attempts to form a whole from disjointed parts. But unlike the natural process of mineral formation, textual accretion is the result of human agency. With each accretion to a text, the speaker of the core text is respoken. Respeaking can be a way for the production authority to modify the ethos of the original speaker or call into question something in her text" (548).

10 This notion of cunning is taken up in work by Marcel Detienne, Debra Hawhee, and Jay Dolmage. Dolmage's discussion is particularly relevant in that he discusses how the disabled God Hephaestus emerges as cunning due to his bodily variation. Because his feet are bent outward, he can walk sideways smoothly and easily and thus is overly mobile.

11 One of many examples of lack of agency in how Barnum represented his performers involves one of Barnum’s first exhibits known as Joyce Heth who was purported to be the 161-year-old nurse of George Washington. One of Barnum’s broadside posters dated 1835 reads: “To use her own language when speaking of the illustrious Father of his Country: 'she raised him'” (Becker). To the author of this broadside, Heth’s own language is only viable through the grammatical third person.

12 Zinham in Working in the Archives discusses Sojourner Truth’s use of photographs to supplement talks (119-20). Leak, however, sold her autobiography alongside photographs.

13 This quote comes from my notes taken at the Representing Disability Conference at Haverford College, Nov., 2006.

Works Cited

Barnum, Phinneas T. Struggles and Triumphs: or, Forty Years’ Recollections of P.T. Barnum, Written by Himself. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger, 2003 (1872).

Bleeker, Sylvester. General Tom Thumb’s Three Year Tour Around the World. New York: S. Booth, 1872.

Bogardus, A. (photographer). “Tom Thumb And Wife On Balcony Gen. Tom Thumb and Wife.” c. 1881. Cabinet Card. Syracuse University, Special Collections. Ronald Becker Collection of Eisenmann Photographs. 3: 881.

Bogdan, Bob. Freak Show. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988.

Brueggemann, Brenda Jo. Lend Me Your Ear: Rhetorical Constructions of Deafness. Washington D.C.: Gallaudet UP, 1999.

Buchanan, Lindal. Regendering Delivery: The Fifth Canon and Antebellum Women Rhetors. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2005.

Campbell, Karlyn Kohrs. Man Cannot Speak for Her. Vol.1, 2. New York: Greenwood, 1989.

Collins, Vicki. “The Speaker Respoken: Material Rhetoric as Feminist Methodology.”

College English, 61:5 (1999): 545-73.

Dolmage, Jay. “Breath Upon Us an Even Flame: Hephaestus, History, and the Body of Rhetoric.” Rhetoric Review, 25:2 (2006): 119-40.

Eisenmann, Charles (photographer). “Mrs. Tom Thumb Lavinia Warren.” c. 1880. Cabinet Card. Syracuse University Library, Special Collections. Ronald Becker Collection of Charles. Eisenmann Photographs. Box 2 No. 206.

--. Ann Leak, Armless Wonder. c. 1888. Cabinet Card. Syracuse University Library, Special Collections. Ronald Becker Collection of Charles Eisenmann Photographs.

Fiedler, Leslie. Myths and Images of the Secret Self. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1978.

Frank Leslie’s Journal. No article title. Feb. 10, 1863.

Fredal, James. Rhetorical Action in Ancient Athens. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2006.

Fretz, Eric. “P.T. Barnum’s Theatrical Selfhood and the Nineteenth-Century Culture of Exhibition.” Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body, ed. Garland-Thomson. NY: NYUP, 1996.

Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. Extraordinary Bodies. New York: Columbia UP, 1997.

--. Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body. New York: New York UP, 1996.

Glenn, Cheryl. Rhetoric Retold: Regendering the Tradition from Antiquity Through the Renaissance. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 1997.

Johnson, Nan. Gender and Rhetorical Space in American Life, 1866-1910. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 1991.

Leak, Ann E. The Autobiography of Ann E. Leak, Born Without Arms. Boston: Press of Carlton and Carlton, 1871.

Lewieki-Wilson, Cynthia and Jay Dolmage. “Refiguring Rhetorica: Linking Feminist Rhetoric and Disability Studies.” Rhetorica in Motion: Feminist Rhetorical Methods and Methodologies, ed. E. Schell & K.J. Rawson. Pittsburgh: U of Pittsburgh Press, 2010.

“The Loving Lilliputians: Warren-Thumbiana, Marriage of General Tom Thumb and the Queen of Beauty...” New York Tribute (Times) . Feb. 11, 1863.

“Mrs. Lincoln gives small evening reception for 50 guests in honor of “Gen. Tom Thumb” [Charles S. Stratton] and bride [Lavinia Warren].” Washington Chronicle. February 14 1863.

Quayson, Ato. Aesthetic Nervousness: Disability and the Crisis of Representation. New York: Columbia UP, 2007. Print.

Ronald G. Becker Collection of Charles Eisenmann Photographs. Syracuse University Library Special Collections. http://library.syr.edu/information/spcollections/digital/eisenmann/

Royster, Jacqueline Jones. Traces of a Stream: Literacy and Social Change Among African American Women. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2000.

Schweik, Sue. “Begging the Question: Disability, Mendicancy, Speech and the Law.” Narrative, 15.1 (Jan 2007): 58-70.

Warren, Countess Lavinia. The Autobiography of Mrs. Tom Thumb: Some of My Life Experiences. Hamden: Archon Books, 1979.