Alex Reid, SUNY Buffalo

Enculturation 8 (2010): http://enculturation.net/exposing-assemblages

Over the last decade the crisis in scholarly publication has become as familiar a topic in English Studies as the national decline in undergraduate majors and the disappearance of tenure-track positions. Increasing demands for publication for tenure and promotion have combined with shrinking markets, particularly for monographs. The emergence of online journals has relieved some of those pressures, even though the scholarly reputation of those journals has been slow to improve. More recently, university presses have begun to move to electronic publishing. In March 2009, the University of Michigan Press announced it would adopt digital publication. In an open letter, the Press’ Director, Philip Pachoda, writes that “we will publish all new academic monographs primarily in a range of digital formats, while also making high quality print versions available on request for bookstores, institutions, individuals and authors” (Pachoda). Pachoda explains, “Digitized books will be candidates for a wide range of audio and visual digital enhancements—including options like hot links, graphics, interactive tables, sound files, 3D animation and video—allowing authors to better communicate the subtleties of their work.” A similar move has occurred at Utah State University Press, where there was a clear acknowledgement of the combination of economic pressures and the recognition of some imperative or at least opportunity to grow in the area of open access, digital publication. Within rhetoric and composition, the Computers and Composition Digital Press (CCDP), which is an imprint of Utah State University Press, was formed in 2007. The CCDP website states that the press “is committed to publishing innovative, multimodal digital projects. The Press will also publish ebooks (print texts in electronic form available for reading online or for downloading); however, we are particularly interested in digital projects that cannot be printed on paper, but that have the same intellectual heft as a book” ("Missions and Goals"). From these initial, but significant, moves from university presses to broader technological shifts, including the growing popularity of e-book readers, it would seem clear that this new decade will mark a decided shift away from the print publication of scholarship.

That said, aside from unique imprints like CCDP and a few journals, like Kairos, which have a tradition of encouraging scholars to produce scholarship in a variety of media, the majority of digitally published humanities scholarship continues to replicate nearly all of the features of the print journal article (aside from actually being printed on paper). Pachoda notes Michigan’s intention to continue to make publications available in print upon request. This would seem to echo the practice of making PDFs of print articles available through subscription databases, which would be, by far, the most common form of digital scholarship (if one were inclined to count it as such). Beyond digitized copies of print articles, most online articles are as linear and text-based as their print brethren. There are advantages to access and searchability inherent to digital media, and such articles can include active links to online references, but, for the most part, particularly in terms of the composition of such digital scholarship, there is little difference between these digital articles and print ones. That is, as a scholar, one is likely to compose an article for an online journal in the same way as one would compose a print journal article; the reviewing and editing procedures are also fundamentally the same in online and print venues. In fact, this similitude is a compelling argument for valuing online journals as equivalent to print ones. That said, in the last five years, a range of technological innovations have made the basic production and dissemination of video accessible to all scholars (and millions of other Internet users). YouTube is evidence of this. While video content may be slowly making its way to scholarly journals, videos of scholars giving course lectures or presentations are now easy to find online. One can also find a growing number of born-digital projects: instructional screencasts, slidecasts of conference papers, video blogs, and so on. In short, video scholarship already exists in a variety of forms, but the relation of these videos to more conventional scholarship, as well as to the rest of the academic community, is uncertain.

This essay neither purports to offer a solution to this situation nor imagines some idealized video scholarship community. To the contrary, as I explore, this confluence of the marketplace woes for academic publishing, the general exhaustion of humanities scholarship, and the emergence of digital media networks creates an opportunity for engaging more fundamentally with the scholarly projects of humanism. That is, digital video scholarship is not a palliative that will allow humanist scholarship to continue trundling along for another decade (or until some other technology replaces it). Instead, as I will explore, the current situation offers scholars the opportunity to investigate the material and social assemblages that have coded and territorialized the humanities over the last century. As I will discuss here through the work of Jean-Luc Nancy, Giorgio Agamben, Manuel DeLanda and others, the investigation of these assemblages can productively operate through an understanding of exposure. Specifically, by understanding how scholarly practices, identities, and communities emerge through exposure to shifting material, technological, and social assemblages, new potentials for humanism might emerge.

Typically, these challenges are framed in technical, rhetorical, and disciplinary terms. Even though the production of digital media, video in particular, has become cheaper and easier, technical hurdles still remain. There is clearly a significant gap between having the basic technical skill and equipment to make a video and having the skill and equipment to make a professional video. The issue of technical production standards becomes a rhetorical concern, an issue of authority, but that is not the only rhetorical concern, as video scholars must decide what existing filmic techniques are appropriate for scholarship. Since it would be impractical to imagine digital scholarship as simply replacing print scholarship (i.e. to imagine video as accomplishing the same rhetorical tasks in the same way as print), these concerns are not only rhetorical but also disciplinary. That is, the movement to video cannot be viewed as a means to continue disciplinary work in a new medium. Instead, the move toward digital scholarship (and pedagogy) begins with recognizing that existing disciplinary practices have emerged from exposure to particular historical assemblages of material, technological, and social objects. In other words, though there is no intrinsic relationship between the humanities and the monograph or the journal article, the humanities’ exposure to the assemblages of digital media networks will mean a shift in disciplinary practices and identities. The humanities might continue without print scholarship, but it will unavoidably be a different humanities, just at the humanities of the twentieth century differed from that of the nineteenth century. So while the technical, rhetorical, and disciplinary concerns remain salient, they must be understood within the broader context of the assemblages to which the humanities are exposed.

As this essay explores, the conditions of exposure occur in all communities, including traditional, print-mediated scholarly communities, though disciplines have created many mechanisms to close off the possibilities of exposure. Similarly, as the video below investigates, both mainstream and academic discourses have argued for the development of a critical, digital literacy to protect against exposure by and to social, digital media networks. In both cases, digital media are viewed as external forces threatening an existing internal identity rather than as part of a new assemblage through which contemporary identities will be produced. As Agamben notes of such critical gestures, this is “the vanity of the well-meaning discourse on technology, which asserts that the problem with apparatuses can be reduced to the question of correct use. Those who make such claims seem to ignore a simple fact: If a certain process of subjectification (or, in this case, desubjectification) corresponds to every apparatus, then it is impossible for the subject of an apparatus to use it ‘in the right way’” (What is an Apparatus? 21). That is, it is only through exposure to apparatuses that subjectivities and communities emerge: the question of ethics can only be understood through an exposure to these apparatuses not as a shield against such exposures. This observation applies equally to both traditional academic scholarship and social, digital media networks. Both would be apparatuses in Agamben’s sense of the term as “literally anything that has in some way the capacity to capture, orient, determine, intercept, model, control, or secure the gestures, behaviors, opinions, or discourses of living beings” (14). That is, for Agamben, the apparatuses of academic scholarship would produce academic subjects (i.e. scholars) and secure their use of the apparatuses (i.e. their production of scholarship) just as thoroughly as social, digital media networks produce user-subjects and manage their use of networks. However, as I will argue it, it would be an error to imagine these as apparatuses as totalizing in their power or as neutral translators of some abstract ideological power. As such, it may be useful to move into a broader conception of assemblage in order to explore these possibilities for emergence through what Manuel DeLanda terms “a realist approach to social ontology” (1). Indeed assemblage theory might allow for moving beyond “living beings” and “social ontology” into a more general mapping of object relations, though the focus here on video and scholarship certainly includes both living beings and social ontologies.

Though I am linking together Agamben’s apparatus and DeLanda’s assemblage, I do not intend to suggest they are fully equivalent or interchangeable. Agamben clearly differentiates between living beings and apparatuses; assemblages include both. That said, the apparatus cannot simply be subsumed within the assemblage. As Agamben deploys the term, “The anthropological machine of humanism is an ironic apparatus that verifies the absence of a nature proper to Homo, holding him suspended between a celestial and a terrestrial nature, between animal and human—and, thus, his being always less and more than himself” (The Open: Man and Animal 29). As he continues elsewhere, “through these apparatuses man attempts to nullify the animalistic behaviors that are now separated from him and to enjoy the Open as such, to enjoy being insofar as it is being” (What is an Apparatus? 17). In short, our connection to apparatuses is an integral part of our humanity while also serving as the primary mechanism of an increasingly expansive disciplinary society. For Agamben, this situation calls for “the profanation of apparatuses—that is to say, the restitution to common use of what has been captured and separated in them” (24). This profanation is, at least in part, a process of exposure. As I will discuss, where objects are made sacred by removing them from common use, they are conversely made profane by their exposure to non-sacred spaces. In this context, assemblage theory offers a means to map material, technological, and other social forces and uncover points of exposure and profanation. Here I also turn to Nancy to consider these issues in terms of the interruption of the myth of the writer/author as an immanent force. This interruption, initiated by the experience of exposure, returns the composing from an internal space to external relations. This “being-with,” as Nancy terms it, offers a different way of understanding the composing communities of scholarship that might be opened by the experience of exposure presented to us by video and other digital media. Though there are certainly points of difference among these theories, my interest here in is linking them (rather than resolving or adjudicating their differences) to see where they might go. What Gregory Ulmer notes about electracy applies equally well here: “I assume that the ethical dilemma of self/other will not be solved in an electronic apparatus, but simply that it will become irrelevant, just as ‘appeasing’ the gods, which was the problem addressed by ritual, becomes irrelevant in literacy” (114). Put differently in the terms that will emerge in this essay, the exposure of scholarly practices to new assemblages, including digital media technologies and networks, profanes “sacred” (despite being secular) humanistic practices. Indeed it is particularly the radical redefinition of self/other in the relations of exteriority that characterize assemblage theory that might offer, not a solution, but something other to do.

From the journal article to the journal video?

In considering what new scholarly practices might emerge, it is useful to give some consideration to the processes that resulted in the development of existing scholarship. Though the first academic journals began with scientific societies in the mid-seventeenth century, the oldest journals in English Studies (e.g. PMLA) date to the 1880s. While certainly there are rhetorical and methodological differences between the scholarly discourses of then and now, the deployment of the technological affordances and general purposes of the print journal are largely the same. The creation of PMLA was a central topic of the 1884 MLA Convention in New York, where it was agreed that: “Whatever should be done to bring us nearer together and give us a sense of centralized power, this Journal idea was thought to be of the greatest importance, as through it every man could have a chance to make his views known, and to have them criticized by the body at large” ("The Modern Language Association of America" v). As this passage suggests, faculty in English Studies have historically worked independently. In part this might reflect disciplinary-ideological commitments to certain views on the relationship between writers, texts, and readers. It also reflects the material nature of our work. That is, while a scientific laboratory may require several people to operate, a book only needs a single reader, and an essay only requires a single author. The solitary nature of English scholarship has also reflected our increasing specialization. As much as one might happily share research with departmental colleagues, how many would really count as part of the disciplinary audience toward which one’s research is directed? (Or more poignantly put, how many of one’s colleagues could possibly be included on a list of reviewers for any journal in which one would seek publication?) As the participants of the 1884 MLA convention realized, at the end of the nineteenth century, the print article was the most effective means for speaking with one’s colleagues (and potentially with a larger academic or public audience).

Much follows upon the distribution of scholarship in the form of journal articles. Why, for example, are scholarly articles 5-7,000 words in length? Why not 10,000 or 3,000? There is a calculation here that begins implicitly with the managerial and material costs in reviewing and editing submissions and printing and distributing journal issues. Pre-publication review is necessary because of the cost limitations of printing and the pressures of the marketplace. Only so many pages can be printed for a journal, and those pages need to have quality material if the journal is to maintain reputation (and subscriptions). To a large extent, our legacy scholarly practices from monograph publication down to our daily work in our offices have been founded on the principles that communicating with colleagues in our field is difficult, that access to scholarly information is scarce, and that publication is expensive. Very little about our disciplinary practices makes sense in the context of networked media, and the only explanation for our continuing to maintain the shape and practices of our academic community is that disciplinary inertia has not yet been overcome by external exigencies. For 125 years, English scholars have been publishing print articles in PMLA. As long as that may seem, it also reflects a distinct historical moment, beginning with the second American Industrial Revolution and reaching to the clearly post-industrial present. It is not difficult to situate the crises of scholarly publication, the job market, and declining majors as symptoms of this larger technocultural shift. Just as the modern profession of English studies took shape through the MLA in the wake of America’s electrification, the current crises in our profession mirrors the rise of a new network. While I do not mean to suggest a simple causal or deterministic relationship between these events, I would not be the first to suggest that the emergence of a new technoculture means new opportunities for scholarly community and the chance to build a critical and productive relationship with the emerging post-industrial economy and culture, just as the second industrial revolution offered similar opportunities to English professors in the late nineteenth century. All this provides a backdrop for the particular concern of the role digital video might play in the evolution of scholarship in our field. No longer can we say, as our nineteenth-century colleagues did, that the journal article represents the most cost effective or efficient means for us to communicate and collaborate with other scholars in our field.

Video scholarship arrives amidst this context. The current state of digital video scholarship in the humanities largely takes the form of talking heads. These can be seen on university channels on iTunesU, on YouTube (or any number of sites similar to YouTube, such as Blip.tv, Ustream, or Vimeo) and on more specialized sites like TED.com, BigThink or Fora.tv. In some cases, these videos are little more than home-movie-production-quality documentation of a classroom, conference presentation, or public lecture. Others might have better production quality but are still recordings of events that are given first and foremost for the audience in the room. Less common are talking head presentations that are born-digital in the sense that they were produced for a networked audience. Scholarly videos that go beyond the talking head model to engage with video in different ways remain the rarest variety of digital scholarship. The most well-known example of this genre is Michael Wesch’s “The Machine is Us/ing Us,” with now over 10 million views on YouTube. Wesch’s video shows at once the creative power and the limitations for how we have imagined video scholarship. His video is engaging and thought-provoking. It has been the subject of discussions among scholars and often referred to in scholarship on the digital humanities. Certainly, the video skyrocketed Wesch personally to become a new media academic star. But is the video itself “scholarly”? It is only four and half minutes in length. Certainly no one would want to watch a 20-minute video that adopted the rhetorical-compositional strategies of Wesch’s video, but a short video cannot hope to develop the kinds of scholarly arguments and analyses we expect of the journal article. One might view Wesch’s video as scholarly while simultaneously recognizing that the humanities could not carry forward its research using such videos alone. And this is the primary recognition that ought to arise from an examination of any of these sites or videos: the videos do not “stand alone.” Instead they are part of a media network linking the videos to other videos, as well as to text-based discussions. One can see this on YouTube where users can post “video responses” and “text comments” or watch “related videos.”

Shifting from a focus on the individual video to its networked context reveals a more fundamental, unnecessary assumption at work here. The single-author journal article begins with the assumption that the author is practically separated from her colleagues. Any investigation into the possibilities of digital scholarship must begin with recognizing that our relations with the scholarly community have been altered. Online, every day, one might interact with, potentially, the largest academic conference ever convened. More practically, digital networks offer us the ability to develop and share disciplinary knowledge with a smaller, more manageable group of colleagues in real time. For example, today is November 6th, 2009. I am working on a networked laptop, typing this sentence. Assuming the best outcome, this article will not be published for another six months. Once it is published, it will be static. Alternatively, right now, I could be sharing this document in a variety of networked spaces (Google Docs, for instance) with six, ten, or one hundred colleagues. It wouldn’t be “my” document. Instead, we would be working together on the issue of digital scholarship. We wouldn’t necessarily be trying to compose a single, 7,000-word essay. How might we understand how that could work? One possible approach requires understanding digital scholarship as part of a social assemblage.

Social assemblage theory

Underlying social assemblage theory is a shift from mapping relations between interiorized organic totalities to mapping exteriorized parts characterized by both properties and capacities. Within the conception of relations of interiority one distinguishes between relations that define identity or totality and those that are extraneous to that definition. As such, for example, being part of a crowd at a stadium would be an extraneous relation that did not impinge on the organic totality of an individual within the crowd. Of course, such relations could shift and alter the individual, as in the case of “crowd mentality,” but even given this, the individual would still be an interiorized totality, separable from the crowd. As such, in this model, exposure to the outside always represents a potential threat to the interiorized totality of the organic whole. Conversely, when taking up relations of exteriority, “the properties of the component parts can never explain the relations which constitute a whole” (DeLanda 11). Instead, the properties of the whole “are the result not of an aggregation of the components’ own properties but of the actual exercise of their capacities. These capacities do depend on a component’s properties but cannot be reduced to them since they involve reference to the properties of other interacting entities” (11). In this model, an individual cannot simply be defined by the properties of the parts that define him or her, as parts also are characterized by capacities that exist in a potential or virtual state and only arise through relations of exteriority. Individuals as subjects are not produced through the interiorized relations of the properties of the subject’s component parts; instead the subject only emerges through the exteriorized relations (or assemblages) between parts that actualize particular capacities. In other words, rather than being threatened by exposure, subjectivity can only arise through exposure to the capacities actualized through relations of exteriority.

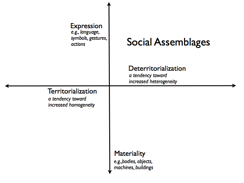

Figure 1: DeLanda's map of exteriorized relations

Taking up the work of Deleuze and Guattari, DeLanda maps the exteriorized relations of social assemblages along two axes (see fig. 1). The first axes travels from materiality to expression; the second axes shifts from territorialization to deterritorialization. Many assemblage components have material roles in a social assemblage, including “a set of human bodies properly oriented (physically or psychologically) towards each other” (DeLanda 12). In addition to bodies, one would also include any objects that are part of a material location: for example, food, furniture, various tools, etc. Those components, along with others, also exercise their capacities for expression. The obvious examples are verbal expressions, but one might include bodily expressions or gestures or the expressive characteristics of objects (e.g., the taste of the food, the comfort of the furniture). Along the other axes, territorialization is the tendency of a space toward organization and increasing homogeneity: for example, a meeting room that is part of a department’s offices on a university campus. Deterritorialization then is a tendency to disrupt spatial boundaries or increase heterogeneity. DeLanda notes, “a good example is communication technology, ranging from writing and a reliable postal service, to telegraphs, telephones and computers, all of which blur the spatial boundaries of social entities” (13). As such the homogeneity of the department meeting room might be deterritorialized by video conferencing or even a memo from an external agency. Of course, these examples can only go so far. Certainly, one can see within disciplinary assemblages that the potential deterritorializing effects of scholarly communication are recaptured by the territorializing tendencies of the various spaces through which those messages pass.

In addition to these two axes, Deleuze and Guattari identify two thresholds where expression shifts in function: the emergence of genetic and linguistic codes respectively. It is the second, linguistic threshold that is particularly relevant here:

The temporal linearity of language expression relates not only to a succession but to a formal synthesis of succession in which time constitutes a process of linear overcoding and engenders a phenomenon unknown on the other strata: translation…The scientific world (Welt, as opposed to the Umwelt of the animal) is the translation of all of the flows, particles, codes, and territorialities of the other strata into a sufficiently deterritorialized system of signs, in other words, into an overcoding specific to language. This property of overcoding or superlinearity explains why, in language, not only is expression independent of content, but form of expression is independent of substance. (62)

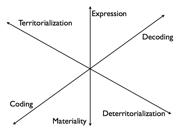

Figure 2: DeLanda's third axis

DeLanda modifies Deleuze and Guattari’s approach somewhat to conceive of these processes as a third axis of the assemblage, “in which specialized expressive media intervene, processes which consolidate and rigidify the identity of the assemblage, or, on the contrary, allow the assemblage a certain latitude for more flexible operation” (see fig. 2) (19). The addition of the third axis allows for the investigation of linguistic expressions as secondary processes of territorialization, as codings, or alternatively as decodings intensifying deterritorialization. This axis is of particular interest for the concerns of this essay, as through it DeLanda provides a means for investigating how media destabilize assemblages.

Taking up DeLanda’s examples, one might hypothesize that social assemblages whose materiality and expression are largely mediated by communication networks might have a greater tendency toward deterritorialization and heterogeneity than those where such technologies do not play as integral a role. This is certainly clear in the contemporary classroom, where the students’ access to mobile networks deterritorializes the traditional academic territory. In scholarly terms, the traditional location of research (i.e. somewhere in the bowels of an academic library) increased the homogeneity of those with access. Even subscription-based, full-text databases serve this function, though certainly some increase in heterogeneity is visible there. As one moves along the continuum of media networks from open access journals and blogs to videos uploaded to YouTube, the deterritorializing effects become more visible. This effect is, in part, the operation of communication networks as destabilizing traditional territorial boundaries but is also the result of potential decoding within the particular media communicated along the media. That said, one should not mistake this observation for a statement about increased political freedom or agency, let alone some inherently liberatory quality of the technology. It is certainly possible, in the future, that academic disciplines might capture media networks as territorializing forces and produce media messages that serve to overcode those territories. That is certainly what has transpired with the print networks and journal media of traditional scholarship. Indeed there is already a fair amount of homogeneity in video scholarship inasmuch as that scholarship is constituted by video recordings of heavily territorialized spaces (e.g. the lecture hall or conference presentation). That said, the scholarly video invested in media networks connects with deterritorializing relations of exteriority, where the coded expressions of scholarly discourse take up new relations and new capacities, and the human bodies, who were once comfortably coded and territorialized as authors and scholarly readers, find themselves exposed to new relations and becomings.

Exposure and the myth of immanence

Unfortunately, this conception of exposure to the exteriority of relations is largely absent from both mainstream and academic conversations regarding social media, and it certainly does not appear to play a role in our discussions of digital scholarship. Despite the discipline’s fluency with various theoretical critiques of authorship, as scholarly authors we continue to view our own writerly identities in very traditional ways. Student writers are seen in the same terms. As Diane Davis notes, “Even radical writing pedagogies, that is, which presume that identity is constituted and plural, have a tendency to reproduce the myth of immanence by encouraging students to consider themselves presentable” (121). That is, conventional writing pedagogies view students as self-present, internalized subjects, but even those who critique such notions as the production of cultural-ideological forces aim “to help the student writer become conscious of and then to speak from her own radical positioning—that is, to embrace an identity founded on that positioning and to disclose it in writing as the basis for her own arguments and ideas” (121). Typically, we understand our own scholarly authority in the same ways. In the end, after the theorizing of how subjects get produced, we say there remains an immanent being, me, Alex Reid, and I can present myself in this text. Against this widespread conceit, Davis argues that it is necessary “in our field today to begin elaborating a kind of ‘communitarian’ literacy, a literacy which presumes first of all that writers and readers are in the world and exposed to others, a literacy that can read and write writing as a function of this irreparable exposure, of this irrepressible community” (122). Davis’ concerns stand separate from the specifics of digital scholarship. The challenges of externalizing the subject, of inclining toward the community (as Jean-Luc Nancy puts it), as opposed to insisting upon an immanent, self-contained, self-presentable author, exist as much in the world of print as they do within digital contexts. That said, as I have been arguing, the shift in the technological, material assemblages of composition into digital networks reformulates our view of and experience with compositional practices. In short, the externalization of the subject in the emergence of community, which is difficult and abstract in the print world, becomes more palpable and material in digital media networks. Furthermore, this palpability is even intensified by the shift from text into video.

Following along this logic, video might offer more opportunities to pursue a communitarian literacy through the interruption of the myth of the writer. As Nancy explains, where this myth is interrupted, the writer “is not the author, nor is he the hero, and perhaps he is no longer what has been called the poet or what has been called the thinker; rather, his is a singular voice (a writing: which might also be a way of speaking). He is this singular voice, this resolutely and irreducibly singular (mortal) voice, in common: just as one can never be ‘a voice’ (‘a writing’) but in common” (70). This being-in-common is a being-with rather than a being-inside. That is, the conventional notion of community suggests a sharing of interiorized characteristics: a particular religious faith, a passion for a hobby, an ideological viewpoint, etc. Nancy suggests “‘with’ implies proximity and distance, precisely the distance of the impossibility to come together in a common being. That is for me the core of the question of community; community doesn’t have a common being, a common substance, but consists in being–in–common, from the starting point it’s a sharing, but sharing what? Sharing nothing, sharing the space between” (Nancy et al.). In this formulation we are each singular beings who arise through our exposure to one another, through a being-in-common, not through a sharing of characteristics so much as through the interaction of the capacities of the assemblage we produce.

In a more accessible discourse, as captured in the video, Rheingold notes that “the nation state and the online community have something in common, which is that they are imaginary.” The first response to imaginary is to interpret this as meaning states and online communities do not exist, that they are not real in the sense that more immediate communities might be. Typically, however, we move to a second definition that accounts for the “imaginary” as an operation of ideology and/or power in which subjects are products of the characteristics they receive from their attachment to these institutions. It is ultimately in such formulations that exposure appears as a threat to the self. Without denying ideological power, in taking up the exteriority of relations, one discovers, as Agamben describes, that “belonging, being-such, is here only the relation to an empty and indeterminate totality” (The Coming Community 66). That is, one might be related to a nation-state or online community, but that relation does not pass along determining characteristics to an interiorized being threatened by this exposure. Instead, Agamben echoes Nancy’s emphasis on the “space between:” “Whatever adds to singularity only an emptiness, only a threshold: Whatever is a singularity plus an empty space, a singularity that is finite and, nonetheless, indeterminable according to a concept. But a singularity plus an empty space can only be a pure exteriority, a pure exposure. Whatever, in this sense, is the event of an outside” (66, emphasis original). The imaginary then describes these relations of exteriority, our relations not only with this or that community, but with what Kevin Kelly terms in his TED talk, the “one machine:” our exposure to the collective operation of the web. As Agamben continues, “The outside is not another space that resides beyond a determinate space, but rather, it is the passage, the exteriority that gives it access” (67). In other words, as one conceives of this imaginary relation, this being-with or -in-common, this relation of exteriority, as a relation of an “outside,” one should not conceive this outside as a beyond but rather as a surface (e.g. as in the phrase “the skin is the outside of the body”) or more precisely as a threshold or point of access. Nancy takes care to note that in such relations “there is no penetration into, there is everywhere only a touching” (“Love and Community”). Even in those sexual acts that are typically understood as “penetration,” Nancy sees a touching characterized by both proximity and distance. Ultimately what one uncovers here is a different topology from one that ascribes a defined inside and outside. Instead one encounters a fractal or inter-dimensional space where boundaries do not close-off to define objects as two- or three-dimensional. Hence the imaginary relation, one’s exposure to the online community, is a relation of touching, of proximity and distance, along an outside or threshold, where capacities emerge to shape assemblages. The voice, the “authorial voice,” can never be the product of an interiorized being, immanent to itself. Instead the voice is always a product of exteriority, of touching: “The body is first a hole, a tube if you want, and around the tube is a skin. The first character of this topology is that it is a resounding thing. The air can go through the tube and you have the skin over it and you produce music. The body is first a certain sound, and that sound is the voice” (Nancy et al.). Obviously there can be no voice without air passing through and over the body’s thresholds. In a similar and no more abstract fashion, there can be no writing without a touching of the outside. The text itself is one such threshold, a point of exposure, that writer and reader both touch. Such exposures then must also move beyond these bodily examples as well. While there can be no voice without air passing over the body’s thresholds, there can be no language without exposure to an assemblage of material, technological, and social objects. Taking this further, to find one’s “voice” in digital video involves exposure to an extensive array of processes, as I explore below.

Virtual Community, Virtual Immanence, Virtual Exposure

Available for download via Vimeo and via Enculturation

Virtual Immanence, Virtual Community, Virtual Exposure

While social assemblage theory can operate to map the broader picture of digital video entering scholarship, it is arguably even more effective when it begins from a particular site of scholarly production: for example, the production of the video embedded in this essay. To begin, the materials involved in video production are different than those used for composing an essay: new hardware, software, and peripheral technologies come into play. As such, the capacities for expression certainly shift in a radical way in the move from text to video. Though I am using the same computer to write this essay and produce this video, a MacBook Pro, I am clearly using them in different ways, and the differences are not solely in terms of the software I am using. For example, I have used the built-in webcam and microphone to record audio and video. I’ve also made use of a Flip video camera. If one adds in the access to media networks, heterogeneity increases dramatically. Not surprisingly, in writing this essay I have made extensive use of this network connection to conduct research. Scholars do this today regularly without giving much thought to how a different information architecture or archiving procedure or copyright law would dramatically reframe their research practices. However, the video would quite simply have been impossible without network access to the video footage and background music I downloaded.

Much of the material for the video comes from the BBC "Digital Revolution" collection: video that has been produced for part of a planned series on digital media and released on the web for public use. Other parts come from interviews made for the Internet as Playground and Factory conference. The footage of Kevin Kelly, the founding executive editor of Wired, comes from the TED conference. As noted in the works cited, there are a few snippets of video from YouTube, and music taken from a Creative Commons music sharing site, CCMixter. The video includes web business gurus Charles Leadbetter and Chris Anderson, technology writers Howard Rheingold and Douglas Rushkoff, and a number of academics and researchers: danah boyd, Sherry Turkle, Jean-Luc Nancy, Giorgio Agamben, Mackenzie Wark, Clay Shirky, Nick Monfort, Alex Halavais, and David Weinberger. Even with a relatively simple video editing program like iMovie, it is then possible to cut selections from the downloaded video; adjust color, audio and other qualities of the video; apply simple effects and transitions; add text, voiceovers, and music; and export a video in a format distributable on the web. It is perhaps difficult to think of splicing a video clip in an iMovie window as a social assemblage with “material” dimensions, but, as abstract as the relations may seem, the video ultimately resides in a physical location in memory and storage and the operations undertaken in iMovie make permanent changes to the video’s characteristics and capacities. Each of the editorial/compositional actions taken in iMovie has an expressive element that, as media, has a secondary coding and/or decoding. So, for example, in the past, Howard Rheingold sat in his backyard and was interviewed and video-recorded for the BBC. There is an entire social assemblage that one might investigate stemming from that event, but I will forego that here. The result though is that a video of Rheingold is uploaded to the BBC site, where it and he are exposed to web users. I downloaded the video and integrated it as material in a new assemblage that resulted, in part, in the video above. Here, again, Rheingold is exposed to a series of expressions, codings, decodings, territorializations, and deterritorializations, some of which are technical features of the hardware and software I am employing and others of which relate to the rhetorical and disciplinary demands to which I am responding.

Of course, it is more complicated than that. The rhetorical expectations of video are intertwined with technical capacities including everything from sound levels to linking together clips in a manner that results in the experience of some seamless conversation and/or progression of ideas. Disciplinary expectations operate to overcode the potential content of the video, but the video material already comes with its own expressions and codes. As much as Rheingold is exposed to the composition processes I employ, my video is exposed to his facial expressions, intonations, and bodily expressions, as well as the particular content of his interview. Given the general selection of material from these two collections, the BBC and the conference, there was already some built-in continuity. That is, for example, the BBC interviews were produced with the intention that they would be combined into a series of programs; as such they share related content and production strategies. As these pieces are cut and combined, their relations of exteriority activate new potentials, as one clip for one video is juxtaposed with another clip from a different interview. Does it make a difference that danah boyd is interviewed in a mall from a distance while Sherry Turkle is recorded up-close in some indeterminate indoor location? Does it matter that in some videos an interviewer is visible? Each of these characteristics of the video add expressive force to the assemblage. Does the juxtaposition of boyd and Turkle open new capacities for expression that would not have existed if they were not juxtaposed in this manner? As each part is exposed to others, new capacities emerge and the assemblage as a whole shifts. In turn, these assemblages intersect with the production of my video recording myself, in terms of the content of what I say, my nonverbal expression and mood, and the aesthetic-rhetorical approach of the production. Background music adds another expressive mood to particular segments and lends a sense of cohesiveness to the spliced-together clips. While, hypothetically, thousands of Creative Commons-licensed audio clips are available for download, there are limitations to how much time one could actually spend searching for appropriate music. Regardless of the selection process, one is ultimately also exposed to the particular material and expressive characteristics of the music and the capacities that emerge between the music and the video. It is only through these relations of exteriority that the video assemblage emerges. This is perhaps most clear in the crescendo-like montage near the end of the video. Here there is an experience of synthesis, of reterritorialization and overcoding. In this case though, the montage is a different rhetorical trick, as I interrupt the process to call attention to the way a video assemblage might obscure the exposures in the video with a turn toward a myth of immanence, where self-immanent beings come together in a totality to which the self remains, in contradiction, unexposed.

Conclusion

Through the mapping of the social-material assemblages of scholarly video production, one can develop tactics for investigating and activating these thresholds, these relations of exteriority. From this perspective, one would see exposure as an integral element of all composition and communication, with the added caveat that, within some assemblages, processes of territorialization and coding tend to limit the potential for mutation. At the current moment, the overcoding and territorializing forces common to print scholarship are not as strong or prevalent for video scholarship, and media networks further deterritorialize these practices by disseminating video beyond the reach of disciplinary organizing forces. Instead, in the crowded space of a social media network where scholars post videos and texts, sometimes in direct response to others, other times as tangential compositions, and yet others as intentionally collaborative efforts, there are regular opportunities for exposure. In a way, it is what scholars fear most: to be exposed (as frauds, etc.). Perhaps it is that fear that keeps many scholars from blogging or Facebook or even posting on email listservs, or perhaps it is the recognition that scholarly identity and authority are secured by remaining within disciplinary territories. In this same moment, however, these overcoding and territorializing forces appear to be approaching a crisis in operation as the traditional mechanisms of scholarly publication, hiring, and student enrollment in our majors falter. It is here that one might think in terms of Agamben’s apparatus. The pseduo-sacred qualities of the humanities, if not the university in general, face exposure and profanation in social media. This is both threat and opportunity. Exposure to the decoding, deterritorializing potential of a communitarian video network might present scholars with opportunities to produce new assemblages, new relations of exteriority, that might lead scholarship and discipline into new, more productive and dynamic activities. Davis has already suggested how communitarian writers might take up relations of exteriority: “They do not aim to establish a stable and authoritative ethos nor to put forth an unambiguous message; they aim to amplify the irreparable instability and extreme vulnerability to which any writing necessarily testifies” (139). As such, the point is neither to turn scholarship toward video because it is intrinsically better than print, nor because video represents something exciting or attractive. In fact, scholarly engagement with video may only be transitory on a path elsewhere. Indeed, that engagement will undoubtedly be transitory, if only in the sense that one may now realize that our engagement with print has been transitory. Instead, the “point” is to consider what particular opportunities for transit video networks might offer. This consideration will include an examination of, and experimentation with, the technical, rhetorical, and disciplinary parts of scholarly video network assemblages, where one will engage the particular capacities that emerge among these relations of exteriority. Through video network scholars’ exposure to these thresholds new potentials for humanistic scholarship and community might emerge.

Works Cited

Agamben, Giorgio. The Coming Community. Trans. Michael Hardt. Minneapolis: U of MN P, 1993. Print.

_____. The Open: Man and Animal. Trans. Kevin Attell. Standford: Stanford UP, 2004. Print.

_____. What is an Apparatus? and other essays. Trans. David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2009. Print.

Davis, D. Diane. “Finitude's Clamor; Or, Notes toward a Communitarian Literacy Author(s).” College Composition and Communication 53.1 (2001): 119-145. Print.

DeLanda, Manuel. A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity. London: Continuum, 2006. Print.

Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans. Brian Massumi. Minneapolois: U of MN P, 1987. Print.

"Mission and Goals | Computers and Composition Digital Press." Computers and Composition Digital Press | Peer-reviewed ebooks and scholarly projects. Web. 11 Nov. 2009.

Nancy, Jean-Luc. The Inoperative Community. Trans. Christopher Fynsk. Minneapolis: U of MN P, 1991. Print.

Nancy, Jean-Luc, Avital Ronell and Wolfgang Schirmacher. “Love and Community: A Roundtable Discussion.” August 2001. Web. 23 Dec. 2009.

Pachoda, Philip. "Letter from the director: Digital transition." The University of Michigan Press. Web. 2 Nov. 2009.

Scholz, Trebor. "Market Ideology and the Myths of Web 2.0." First Monday. 3 Mar. 2008. Web. 28 Dec. 2009.

"The Modern Language Association of America." Modern Language Association of America Proceedings 1 (1884): I-Vii. Print.

Ulmer, Gregory. “Reality Tables: Virtual Furniture.” Prefiguring Cyberculture: An Intellectual History. Eds. Darren Tofts, Annemarie Jonson, and Alessio Cavallaro. Cambridge, MA: MIT P., 110-129. Print.

Video Credits

"3 female avatars go shopping at Armidi in Second Life." Torley. YouTube.com. 5 Mar. 2009. Web. 8 Jan. 2010. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=72zsNzLs7_o.

"BBC - Digital Revolution (Working Title) - Digital Revolution." BBC - Homepage. Web. 25 Dec. 2009. http://www.bbc.co.uk/digitalrevolution/.

"Emanuel Mangengin in Cameroon on mobile phones in Africa." Sjoerd Sijsma. YouTube.com. 3 June 2009. Web. 24 Dec. 2009. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QTh2D5mHH_0.

"The first film ever 'Exiting the Factory' (1895)." AlphaBravoBravoYanke. YouTube.com. 2 Nov. 2007. Web 8 Jan. 2010. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OYpKZx090UE

"Free." Airtone. CCMixter. 19 Dec. 2009. Web. 25 Dec. 2009. http://ccmixter.org/files/airtone/24436.

"The Internet as Playground and Factory - Alex Halavais." Voices from the Internet as Play. Vimeo.com. 1 Dec. 2009. Web. 15 Dec. 2009. http://vimeo.com/7954685.

"The Internet as Playground and Factory - Howard Rheingold." Voices from the Internet as Play. Vimeo.com. 1 Dec. 2009. Web. 15 Dec. 2009. http://vimeo.com/7919949.

"The Internet as Playground and Factory - Ken Wark." Voices from the Internet as Play. Vimeo.com. 1 Dec. 2009. Web. 15 Dec. 2009. http://vimeo.com/6428602.

"The Internet as Playground and Factory - Nick Monfort." Voices from the Internet as Play. Vimeo.com. 1 Dec. 2009. Web. 15 Dec. 2009. http://vimeo.com/8204449.

"Intro to Second Life." Giff Constable. YouTube.com. 24 June 2007. Web. 24 Dec. 2009. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CaLKFeJLnqI.

"Kevin Kelly on the next 5,000 days of the web." TED.com. July 2008. Web. 21 Dec. 2009. http://www.ted.com/talks/kevin_kelly_on_the_next_5_000_days_of_the_web.html.

"New York City Street Walkers." Steve Garfield. blip.tv. 5 Nov. 2008. Web. 7 Jan. 2010. http://blip.tv/file/1435946?filename=Stevegarfield-NewYorkCityStreetWalkers753.MOV.

"Toyota Camry Hybrid Factory Robots." gizmodoAU. YouTube.com. 30 Aug. 2009. Web. 8 Jan. 2010. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=82w_r2D1Ooo.

"Trading Floor at New York Stock Exchange (NYSE)" EH11937. YouTube.com. 9 Aug. 2007. Web. 25 Dec. 2009. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q7FdaiPQuDg.

"Transitions II." Soundprank. CCMixter. 29 Nov. 2009. Web. 25 Dec. 2009. http://ccmixter.org/files/soundprank/24074.

"World of Warcraft Gameplay (HD)." Ddrmaster57. YouTube.com. 18 Jan. 2009. Web. 24 Dec. 2009. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uDel5X-NUIw.