Logos 2

INTRODUCTION || DISIDENTIFICATION || THEORY || TECHNOLOGY || QUEER RHETORIC || LOGOS || PATHOS || ETHOS || TONGUES || WORKS CITED

Many contemporary queers often understand and critically play with such illogics, creating rhetorically powerful counterlogics. We consider the rhetorical collisions produced by the Lesbian Avengers, for instance, who picture women holding guns or bombs, saying “We recruit”—collisions between our culture’s normative understanding of what women are supposed to want versus the rage that many lesbians feel about sexism and homophobia. In Friedrich and Baus’s documentary The Lesbian Avengers Eat Fire, Too, we see the Lesbian Avengers protesting a school board decision not to include a multicultural curriculum. The women take to the streets, shouting angrily. On one hand, these are certainly women concerned for the welfare of children; on another hand, these are women concerned for all children, even those who may not be part of their particular families. The sense of responsibility here exceeds the immediate nuclear family, the locus of concern toward which our culture bends our gaze. The Lesbian Avengers bend it back again, rhetorically critiquing the notion of family in the process.

Later in the film, several Lesbian Avengers perform a communal ritual centered on fire-eating. They demand that their call for rights be addressed, their voices heard, and the fire-eating serves rhetorically to link their speech with power. They take in the fire of their rage (their word), the “fire of action into our hearts, into our bodies.” They resist the fear of being “consumed” by others’ hatred and ignorance of them. Such rhetorically powerful images reverse the normative understanding of what women are, what they are supposed to be, whom they are supposed to love. They insist on queer speech, while overturning the sexist notion that women are necessarily nurturing and thus not interested in revenge or vengeance.

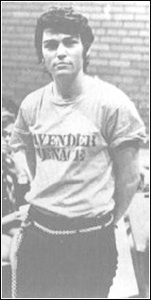

Much of the Lesbian Avengers’ style and forcefulness comes from a tradition of lesbian activism within feminist circles—an activism initially seeking to reverse the silencing of lesbians within feminist movements of the 1960s and 1970s. The second-wave feminist movement, during which the fear of being labeled “lesbians” caused many feminist leaders to distance themselves from the burgeoning gay liberation movement without and the lesbian presence within. The most notorious example of this comes from Betty Friedan, author of The Feminine Mystique and one of the founders of the National Organization for Women. It was widely reported that Friedan had remarked that lesbian feminists were a “lavender menace” that would hurt the women’s movement. The remark led to, first, shoving lesbians back into the closet or purging them from leadership positions in NOW. Second, it led to a powerful counterlogic—the eruption of the lesbian feminist movement, beginning with the twenty-member “Lavender Menace” that disrupted the Second Congress to Unite Women in 1970.

After a consciousness-raising group (including noted lesbian feminists Rita Mae Brown and Karla Jay) noticed that the Second Congress’ program didn’t include any open lesbians, they decided to disrupt the opening session on May 1, 1970. The group, calling itself the “Radicalesbians,” wrote the now-classic manifesto “The Woman-Identified Woman” (“What is a lesbian? A lesbian is the rage of all women condensed to the point of explosion”) for distribution at the event and made purple t-shirts with “Lavender Menace” written across the front. Karla Jay writes:

"I do, I do," several replied. (Jay 143)

Rita Mae Brown in her Lavender Menace t-shirt. Online image.

TOP RIGHT: “Lesbian Avengers Eat Fire, Too.” YouTube.com. RIGHT: Carrie Moyer’s “Lesbian Avengers” poster. Online image.